Home | Category: Science and Nature / Philosophy

ARISTOTLE

Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) is considered the father of logic and the natural science. A pupil of Plato and a teacher of Alexander the Great, he was interested most in the natural world and explaining natural phenomena. He relied on observation to determine the truth, and founded the Lyceum in 335 B.C.

Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) is considered the father of logic and the natural science. A pupil of Plato and a teacher of Alexander the Great, he was interested most in the natural world and explaining natural phenomena. He relied on observation to determine the truth, and founded the Lyceum in 335 B.C.

Aristotle has been called the world’s first and greatest encyclopedist. He seemed to be interested in almost everything he studied. He wrote about logic, metaphysics, ethics, aesthetics, physics, astronomy, drama, and biology. He left behind a wealth of material and remained an authority on nearly everything through the Renaissance. His suppositions were first seriously questioned during the Age of Reason but remained in vogue well into the 19th century..

Based on the number of books written about him (1,696 in 1999 in the Library of Congress collection), Aristotle is the world's 17th most famous person. He ranks behind Jesus and Plato but ahead of Freud and Mozart.

According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “Aristotle is a towering figure in ancient Greek philosophy, making contributions to logic, metaphysics, mathematics, physics, biology, botany, ethics, politics, agriculture, medicine, dance and theatre. He was a student of Plato who in turn studied under Socrates. He was more empirically-minded than Plato or Socrates and is famous for rejecting Plato's theory of forms.

“As a prolific writer and polymath, Aristotle radically transformed most, if not all, areas of knowledge he touched. It is no wonder that Aquinas referred to him simply as "The Philosopher." In his lifetime, Aristotle wrote as many as 200 treatises, of which only 31 survive. Unfortunately for us, these works are in the form of lecture notes and draft manuscripts never intended for general readership, so they do not demonstrate his reputed polished prose style which attracted many great followers, including the Roman Cicero. Aristotle was the first to classify areas of human knowledge into distinct disciplines such as mathematics, biology, and ethics. Some of these classifications are still used today. [Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP) ]

It was Aristotle, equally at ease as a philosopher and as a scientist, whose several treatises on animals laid the foundations of zoology. Aristotle also did important work on plants, although not nearly to the same extent as his thorough publications on animal life, but he did have a strong influence on other scholars, such as Theophrastus, who laid the groundwork for the science of botany.” [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ARISTOTLE’S PHILOSOPHY AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO SCIENCE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ARISTOTLE ON WOMEN, FAMILIES, SLAVERY AND EDUCATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

POETICS: ARISTOTLE ON POETRY, PLOTS, IMITATION, COMEDY AND TRAGEDY europe.factsanddetails.com

ARISTOTLE ON GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT GREEK PHILOSOPHY: HISTORY, PHILOSOPHERS, MAJOR SCHOOLS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Aristotle” by Sir David Ross (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Philosophy of Aristotle” (Signet Classics) by Aristotle, translated by A. E. Wardman, J. L. Creed (2011) Amazon.com;

“Complete Works of Aristotle, Vol. 1 (Bollingen, Oxford translation) by Aristotle, edited by Jonathan Barnes, orginally published in 12 volumes between 1912 and 1954 Amazon.com;

“Complete Works of Aristotle, Vol. 2 (Bollingen, Oxford translation) by Aristotle, edited by Jonathan Barnes (1984) Amazon.com;

“The Nicomachean Ethics” (Penguin Classics) by Aristotle Amazon.com;

“Poetics” (Penguin Classics) by Aristotle Amazon.com;

“Rhetoric to Alexander” (Illustrated) by Aristotle and Aeterna Press (2015), of dubious origin Amazon.com;

“Greek Philosophy: Thales to Aristotle (Readings in the History of Philosophy) by Reginald E. Allen (1991) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Philosophers: From Thales to Aristotle” by William K. Guthrie (1960) Amazon.com;

“Readings in Ancient Greek Philosophy: From Thales to Aristotle” by S. Marc Cohen, Patricia Curd, et al. (2016) Amazon.com;

“Greek Thought: A Guide to Classical Knowledge” by Jacques Brunschwig and Geoffrey E.R. Lloyd (Harvard University Press) Amazon.com;

“The Seekers” by Daniel Boorstin (1998) Amazon.com;

“Early Greek Science: Thales to Aristotle” by G. E. R. Lloyd (1974) Amazon.com;

“Aristotle’s Revenge: The Metaphysical Foundations of Physical and Biological Science”

by Edward Feser (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek and Roman Science” by Liba Taub (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Genesis of Science: The Story of Greek Imagination” by Stephen Bertman (2010) Amazon.com;

“Introducing the Ancient Greeks: From Bronze Age Seafarers to Navigators of the Western Mind” by Edith Hall Amazon.com;

“The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World” by Charles Freeman (2000) Amazon.com;

Works by Aristotle and Links to Them

Aristotle (384-323 B.C.)

2ND Aristotle IEP iep.utm.edu/aristotle

WEB Classics Archive: Aristotle MIT Classics classics.mit.edu ;

Nichomachean Ethics Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

Politics Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

Metaphysics Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

Physics Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

Poetics Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

Poetics MIT Classics classics.mit.edu , excerpts for Teaching

Nichomachean Ethics, excerpts, Ancient History sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

The Politics, excerpts from Books I, III, VII and VIII, Ancient History sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

The Nicomachean Ethics, excerpts from Book 1, Ancient History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

The Doctrine of the Mean, Nichomachean Ethics II:-7 WSU, Internet Archive web.archive.org

Aristotle's Life

Aristotle was born in Stagira, a now extinct Greek colony and seaport on the coast of Thrace in northeastern Greece. His birth there would forever make him an outsider in Athens. Many of Aristotle's relatives and ancestors had a connection with medicine, which was regarded as the most practical and grounded of the sciences. His father Nichomachus was court physician to King Amyntas of Macedonia, and from this sprung Aristotle's long association with the Macedonian Court, which considerably influenced his life. [Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP) ]

Aristotle was born in Stagira, a now extinct Greek colony and seaport on the coast of Thrace in northeastern Greece. His birth there would forever make him an outsider in Athens. Many of Aristotle's relatives and ancestors had a connection with medicine, which was regarded as the most practical and grounded of the sciences. His father Nichomachus was court physician to King Amyntas of Macedonia, and from this sprung Aristotle's long association with the Macedonian Court, which considerably influenced his life. [Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP) ]

While he was still a boy Aristotle’s father died and he became an orphan. At age 17 his guardian, Proxenus, sent him to Athens, the intellectual center of the world, to complete his education. Aristotle studied at Plato's Academy. He was so studious, smart and determined that Plato called him “the mind of the school." Many of the others there called him a “metic," meaning foreigner. Aristotle stayed at the Academy for 20 years and only left when Plato died in 347 B.C. In the end Plato felt betrayed by the direction that Aristotle took with his philosophy and called him “the foal that kicks his mother."

According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: In the later years of his association with Plato and the Academy he began to lecture on his own account, especially on the subject of rhetoric. At the death of Plato in 347, the pre-eminent ability of Aristotle would seem to have designated him to succeed to the leadership of the Academy. But his divergence from Plato's teaching was too great to make this possible, and Plato's nephew Speusippus was chosen instead.

After leaving the Academy, Aristotle drifted for a while. He couldn't return to Stagira because it had been destroyed in battle of conquest by Alexander the Great's father Philip of Macedonia. He set up a small academy in a small kingdom in Asia Minor at the invitation of his friend Hermeas, ruler of Atarneus and Assos in Mysia. Aristotle stayed three year and, while there, married Pythias, the niece and adopted daughter of a king and indulged himself in his passion of studying nature. In later life he was married a second time to a woman named Herpyllis, who bore him a son, Nichomachus. Despite this some scholars have suggested that Aristotle was gay. At the end of three years Hermeas was overtaken by the Persians, and Aristotle went to the island of Mytilene (Lesbos) and spent two years studying biology.

Aristotle spent five years teaching Alexander the Great and 13 years teaching at the Lyceum (See Below). In 323 B.C. During a wave of anti-Macedonian feeling, that followed the death of Alexander the Great and the overthrow of the pro-Macedonian government in Athens, Aristotle was accused of impiety and forced to flee Athens. He ended up in Chaleis on the island of Euboea, where he said: "The Athenians might not have another opportunity of sinning against philosophy as they had already done in the person of Socrates." After living in Chalcis for a year complained of a stomach illness and died in 322 B.C. at the age of 63. He was rich when he died. He left most of his money to his family and freed some of his slaves.

Some scholars have suggested that Aristotle was gay.

Aristotle and Alexander the Great

In 342 B.C., Philip II of Macedonia hired Aristotle to teach science and politics to his 13-year-old son Alexander the Great. The two were together for five years. Little is known about what transpired between the two. Neither Aristotle nor Alexander the Great had much to say about the other afterwards and neither seem to have much influence on the other as they both took very different paths. Even so, according to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy:“Both Philip and Alexander appear to have paid Aristotle high honor, and there were stories that Aristotle was supplied by the Macedonian court, not only with funds for teaching, but also with thousands of slaves to collect specimens for his studies in natural science. These stories are probably false and certainly exaggerated.

One of the few things that Aristotle was recorded as saying was: “the young man is not a proper audience for political science. He has no experience of life, and because he still follows his emotions, he will only listen to purpose, uselessly." Aristotle appears to have written some pamphlets especially for Alexander. They include On Kingship , In Praise of Colones and The Glory of Rices.

The reason Philip chose Aristotle to be Alexander's teacher is not clear. Aristotle was not a well known philosopher at that time. His father served as court physician for Philip's father (Alexander's grandfather) and perhaps Philips choice was a political move aimed at rebuilding Stagira. Aristotle spent three years with Alexander, until he was 16, when he was made a regent while his father Philip was in Asia Minor.

Aristotle was well paid. Philip also helped Aristotle in his studies of nature by assigning gamekeepers to tag wild animals for him. After Alexander became king of Macedonia he gave Aristotle a lot of money so he could set up a school. While he was in Macedonia, Aristotle made friends with the general Antipater, who ran Macedonia while Alexander was on his campaign of conquest. The friendship was close enough that Antipater was the executor of Aristotle's will. Aristotle no doubt received some financial assistance from him as well.

See Separate Article: ALEXANDER THE GREAT AND ARISTOTLE: TEACHING, INFLUENCES AND HOW THEY GOT TOGETHER europe.factsanddetails.com

Aristotle's Lyceum

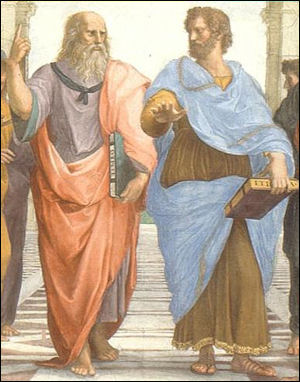

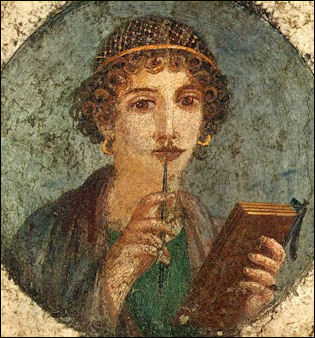

Plato and Aristotle in The

School of Athens by Rafael Aristotle established the Lyceum, a school of learning, in Athens. According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “Upon the death of Philip, Alexander succeeded to the kingship and prepared for his subsequent conquests. Aristotle's work being finished, he returned to Athens, which he had not visited since the death of Plato. He found the Platonic school flourishing under Xenocrates, and Platonism the dominant philosophy of Athens. He thus set up his own school at a place called the Lyceum. [Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP) ]

He taught at the Lyceum from the age of 49 until his retirement at 62. The Lyceum was one of the great schools of philosophy in ancient Greece along with Plato's Academy and the school created by the Cynics after the death of Socrates in 339 B.C. The Lyceum was more than a school. It had an extensive library, gardens and a museum. The library was extensive. Some have called it the first well-organized library. After he died his heirs ordered the books and scrolls buried to keep them out of the hands of his rivals.

Aristotle liked to stroll around the garden while he was teaching. Some people called the Lyceum the Peripatetic School (“the Walking Around” School) because of Aristotle's teaching methods. Morning classes were for serious students. Evening ones for anyone who wanted to come. Afterwards there were often symposium — festive meals — were conducted according to Aristotle's rules.

At the Lyceum, Aristotle divided his time between teaching and composing his philosophical treatises. The more detailed discussions in the morning were for an inner circle of advanced students, while the symposium and popular discourses in the evening were open to the general body of students. In the classes, students didn't just listen to lectures and engage in discussions they also studied the habits of insects and dissected animals. In response to students that complained about the smell and guts, Aristotle told them: “The consideration of the lower forms of life ought not to excite a childish repugnance. In all natural things there is something to move wonder." Aristotle and his students were encouraged to take notes on everything and share them with each other.

Aristotle’s Writing

When Aristotle left Plato Academy he set out on his own to make his own observations on the world and attempted to systematically classify and organize what he saw and thought. In his great work on natural history, the “ Historia Animalium” , he did a series of investigations into "these beings that are the work of nature."

When Aristotle left Plato Academy he set out on his own to make his own observations on the world and attempted to systematically classify and organize what he saw and thought. In his great work on natural history, the “ Historia Animalium” , he did a series of investigations into "these beings that are the work of nature."

Many of Aristotle’s texts were lists of why questions followed by because answers. His arguments often begin with banal assumptions that everyone could agree on, and he then built on them. “Ethics” begins: “Every art and every inquiry, and similarly every action and pursuit is thought to aim at some good.” “ Politics” opens: Every state is a community of some kind and every community is established with a view to do some good.” Even “ Metaphysics” starts that way: “All men by nature desire to know. An indication of this is the delight we take in our senses.”

Aristotle wrote about everything from the habits of bees, to the mechanics of perception to the laws of barbarians. The way he classified things and solved problems in subjects as diverse as biology, logic and politics shaped the vocabulary and way these things were thought about even today. Most of the works that have come down to us today were originally notes and commentary connected to his morning lectures to serious students.

Aristotle’s major works include “Rhetoric” , “History of Animals” , “Metaphysics” , “Ethics” , “Politics” and “Poetics “. Among the 200 or so other titles attributed to him are “On the Gait” , “On Psychology (On the Soul)” , “On Sleep and Sleeplessness” , “Parts of Animals” , “On Prophesying” and “On Longevity, Youth and Age”

According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “The works of Aristotle fall under three headings: (1) dialogues and other works of a popular character; (2) collections of facts and material from scientific treatment; and (3) systematic works. Among his writings of a popular nature the only one which we possess of any consequence is the interesting tract On the Polity of the Athenians. The works on the second group include 200 titles, most in fragments, collected by Aristotle's school and used as research. Some may have been done at the time of Aristotle's successor Theophrastus. Included in this group are constitutions of 158 Greek states. The systematic treatises of the third group are marked by a plainness of style, with none of the golden flow of language which the ancients praised in Aristotle. This may be due to the fact that these works were not, in most cases, published by Aristotle himself or during his lifetime, but were edited after his death from unfinished manuscripts. Until Werner Jaeger (1912) it was assumed that Aristotle's writings presented a systematic account of his views. Jaeger argues for an early, middle and late period (genetic approach), where the early period follows Plato's theory of forms and soul, the middle rejects Plato, and the later period (which includes most of his treatises) is more empirically oriented. [Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP) ]

page 1 of Aristotle's Rhetoric

Aristotle's systematic treatises may be grouped in several divisions:

Logic

Categories (10 classifications of terms)

On Interpretation (propositions, truth, modality).

Prior Analytics (syllogistic logic)

Posterior Analytics (scientific method and syllogism)

Topics (rules for effective arguments and debate)

On Sophistical Refutations (informal fallacies)

Physical works

Physics (explains change, motion, void, time)

On the Heavens (structure of heaven, earth, elements)

On Generation (through combining material constituents)

Meteorologics (origin of comets, weather, disasters)

Psychological works

On the Soul (explains faculties, senses, mind, imagination)

On Memory, Reminiscence, Dreams, and Prophesying

Works on natural history

History of Animals (physical/mental qualities, habits)

On the parts of Animals

On the Movement of Animals

On the Progression of Animals

On the Generation of Animals

Minor treatises

Problems

Philosophical works

Metaphysics (substance, cause, form, potentiality)

Nicomachean Ethics (soul, happiness, virtue, friendship)

Eudemain Ethics

Magna Moralia

Politics (best states, utopias, constitutions, revolutions)

Rhetoric (elements of forensic and political debate)

Poetics (tragedy, epic poetry)

Famous Aristotle works and their English translations

De Anima, Book I. Translated by J. A. Smith

De Anima, Book II. Translated by J. A. Smith

De Anima, Book III. Translated by J. A. Smith

Metaphysics, Book XII. Translated by W. D. Ross

Physics, Book II. Translated by R. P. Hardie and R. K. Gaye

Physics, Book IV. Translated by R. P. Hardie and R. K. Gaye

Politics, Book I. Translated by Benjamin Jowett

Politics, Book II. Translated by Benjamin Jowett

Politics, Book III. Translated by Benjamin Jowett

Aristotle’s Legacy and Preservation of His Work

Pompeii scholar After his death Aristotle’s writings were scattered or lost. It took three centuries just to drag up what remained from underground caches and cellars and put them in a coherent form.By the early Middle Ages all that was left in Europe of Aristotle’s work were a few fragments from “ Logic” . Fortunately, many of his texts had earlier made their way to the great Arab-Islam dynasties in the Middle East, where were translated into Arabic. Centuries later they made their way back to Europe and were translated into Latin. Aristotle views on science endured until relatively recently. Among those who sang his praises were Darwin who called him the great scientist of his time and described other scientists as “mere schoolboys to old Aristotle.”

According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “It is reported that Aristotle's writings were held by his student Theophrastus, who had succeeded Aristotle in leadership of the Peripatetic School. Theophrastus's library passed to his pupil Neleus. To protect the books from theft, Neleus's heirs concealed them in a vault, where they were damaged somewhat by dampness, moths and worms. In this hiding place they were discovered about 100 B.C. by Apellicon, a rich book lover, and brought to Athens. They were later taken to Rome after the capture of Athens by Sulla in 86 B.C.. In Rome they soon attracted the attention of scholars, and the new edition of them gave fresh impetus to the study of Aristotle and of philosophy in general. This collection is the basis of the works of Aristotle that we have today. Strangely, the list of Aristotle's works given by Diogenes Laertius does not contain any of these treatises. It is possible that Diogenes' list is that of forgeries compiled at a time when the real works were lost to sight.” [Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP) ]

The followers of Aristotle became known as the Peripatetics (“Those Who Walk” after Aristotle’s teaching style) The Peripatetic doctrines were introduced into Rome along with other Greek philosophies by the embassy of Critolaus, Carneades, and Diogenes, but were little known until the time of Sylla. Tyrannion the grammarian and Andronicus of Rhodes were the first who brought the writings of Aristotle and Theophrastus into notice. The obscurity of Aristotle's works hindered the success of his philosophy among the Romans. Julius Caesar and Augustus patronized the Peripatetic doctrines. Under Tiberius, Caligula, and Claudius, however, the Peripatetics along with other philosophical schools, were either banished or obliged to remain silent on their views. This was also the case during the greater part of the reign of Nero, although, in the early part of it philosophy was favored. Ammonius the Peripatetic made great efforts to extend the authority of Aristotle, but about this time the Platonists began to study his writings, and prepared the way for the Eclectic Peripatetics under Ammonius Sacas, who flourished about a century after Ammonius the Peripatetic. After the time of Justinian, philosophy in general declined. But in the writings of the scholastics, Aristotle's views predominated. About the 12th century it had many adherents among the Saracens and Jews, particularly in Spain.

Theophrastus, Aristotle’s Successor

“Theophrastus (c. 371—c. 287 B.C.E.) was a Greek philosopher of the Peripatetic school, and immediate successor of Aristotle in leadership of the Lyceum. According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “He was a native of Eresus in Lesbos, and studied philosophy at Athens, first under Plato and afterwards under Aristotle. He became the favorite pupil of Aristotle, who named Theophrastus his successor, and bequeathed to him his library and manuscripts of his own writings. Theophrastus sustained the Aristotelian character of the Lyceum. He is said to have had 2,000 disciples, among them the comic poet Menander. He was esteemed by the kings Philippus, Cassander, and Ptolemy. He was tried for impiety, but acquitted by the Athenian jury B.C., having presided over the Lyceum about thirty-five years. His age is sometimes put at 85, and 107 by others. He is said to have closed his life with the complaint about the short duration of human life, that it ended just when the insight into its problems was beginning. [Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP) ]

Theophratus

“Although Theophrastus generally followed Aristotle's lead in philosophy, he was no mere slavish imitator, and he continued important empirical and philosophical investigations of his own. Very little of his work survives, but he seems in general to have emphasized the empiricist side of Aristotle's thought and downplayed remaining Platonist elements, a trend that was further continued by Theophrastus' successor as head of the Lyceum, Strato. Theophrastus criticized some of Aristotle's arguments for the existence of a Prime Mover, and he expressed dissatisfaction with Aristotle's universal application of teleological (that is, goal-directed) explanations. Theophrastus also composed a large compendium of the doctrines of previous philosophers, which itself is lost, but which probably formed the basis for much of the later doxography which is our main source of information on the pre-Socratic philosophers.”

Aristotle's Long-Lost Tomb Discovered?

In 2016, archaeologists working at the site of the ancient city of Stagira in central Macedonia claim they had discovered the tomb of Aristotle “I have no hard proof, but strong indications lead me to almost certainty," archaeologist Kostas Sismanidis told Sigmalive of the discovery. [Source: The Week, May 26, 2016]

The Week reported: “Aristotle was born in Stagira in 384 B.C. and died in 322 B.C. in Chalcis, where many believed he was buried. However, two literary sources pointed archaeologists to Stagira, where Aristotle's ashes may have later been transferred.

The 2,400-year-old tomb stands in the middle of Stagira with 360-degree views. The top of the dome is at 10 meters and there is a square floor surrounding a Byzantine tower. A semi-circle wall stands at two meters in height. A pathway leads to the tomb's entrance for those that wished to pay their respects. Other findings included ceramics from the royal pottery workshops and fifty coins dated to the time of Alexander the Great. The Byzantines later destroyed the tomb and constructed a tower in its place.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024