Home | Category: Themes, Archaeology and Prehistory / Science and Philosophy

GEOGRAPHY OF ANCIENT ROME AND ITALY

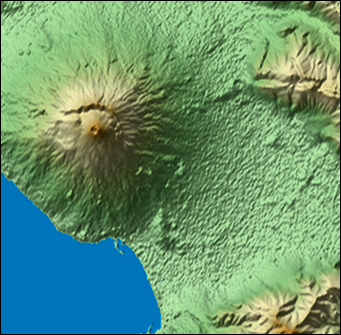

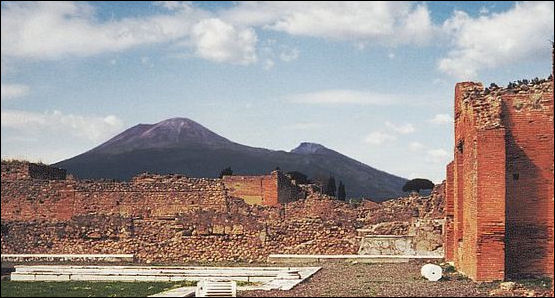

satellite view of Vesuvius The position of the Italian peninsula was favorable to the growth of the Roman power. It was situated almost in the center of the Mediterranean Sea, on the shores of which had flourished the greatest nations of antiquity—Egypt, Carthage, Phoenicia, Judea, Greece, and Macedonia. By conquering Italy, Rome thus obtained a commanding position among the nations of the ancient world. The soil of Italy is generally fertile, especially in the plains of the Po and the fields of Campania. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Bordered by Switzerland and Austria to the north, France and the Tyrrhenian Sea to the west, Slovenia and the Adriatic Sea to the east, modern Italy is a peninsular country shaped like a boot. Separated from the rest of Europe by the Alps, it is 760 miles in length and covers an area of 116,303 square (about the size of Florida and Georgia combined). The leg of the boot is between 100 to 150 miles wide.

About 32 percent of the country is good for agriculture (compared to 21 percent in the U.S.) and the most productive land is around the Po River Valley in the north, the coastal plains and the valleys in central parts of the country (generally areas where there are no high mountains). About 17 percent of Italy is covered by pasture land and 33 percent by forests and woods.

Italy is 80 percent mountainous. The majestic snow capped Alps in the northwest Italy and the magnificent rock spires Dolomites in northeast Italy form a natural border between Italy and France, Switzerland, Austria and Slovenia. Mt. Blanc, Europe's highest mountain, is between Italy and France, the Matterhorn is shared by Italy and Switzerland. Most of northern Italy is drained by the Po river. The fertile and largely flat Po Valley dominates the area south of the Alps and Dolomites.

Another major mountain range, the rugged Apennines runs the length of the Italian peninsula like the spine of a animal. Its highest peaks are around 8.000 feet high. Italy also has two famous volcanos: Vesuvius, which buried Pompeii, is near Naples, and very active Mt. Etna is on Sicily. Umbria and Tuscany in central Italy are characterized by undulating hills with farms, vineyards and Renaissance and medieval hill towns. The southern part of the country is a land of rugged, rocky hills and mountains, vineyards, orange and lemon trees, olive groves and vegetation similar to that found in southern California.

Italy has over 5,310 miles of coastline with Adriatic Sea to the northeast, the Tyrrhenian Sea to the southwest and the Ionian Sea to the southeast. All three seas are branches of the Mediterranean Sea. Off the toe of the boot, like two soccer balls getting kicked, are the islands of Sicily and Sardinia, the largest islands in the Mediterranean. Other notable islands include Capri in the Bay of Naples and Elba in the Tuscan Archipelago.

Much of Italy's western coastline is defined by cliffs, pebble beaches or towns. The best beaches are on Sicily and some of the other islands. Many Europe tourist flock to the beaches on the Adriatic coast around Rimini. The Vatican City (the Papal State of Rome) and San Marino (oldest republic in the world) are separate enclaves within Italy. Major Rivers in Italy include The Po, the Tiber (the river that goes through Rome), and the Arno (the river that goes through Florence).

The Roman empire was at its height in the second and third centuries A.D. At that time it included North Africa (by the conquest of Carthage in the three Punic Wars, 264-146 B.C.), the Holy Land, Egypt, Iberia (Spain), Gaul (France, conquered by Caesar in 56-49 B.C.), Britain (claimed in 43 A.D.), Asia Minor (Turkey), Macedonia (Greece) and Dacia (former Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, conquered in A.D. 117).

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Travel and Geography in the Roman Empire” by Colin Adams and Ray Laurence (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Eternal City: A History of Rome in Maps”

by Jessica Maier (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Atlas of Ancient Rome: Biography and Portraits of the City” (Two Volumes) by Andrea Carandini (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Science of Roman History: Biology, Climate, and the Future of the Past”

by Walter Scheidel (2018) Amazon.com;

“Pliny's Natural History in Thirty-Seven Books” by Pliny and the Elder Amazon.com;

“Rivers and the Power of Ancient Rome” by Brian Campbell (2012) Amazon.com;

“A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome” by L. Richardson Jr. (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Rome” by Chris Scarre (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire” by Kyle Harper (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Climate of Rome and the Roman Malaria” by Corrado Tommasi-Crudeli and Dick Charles Cramond (Classic Reprint) Amazon.com

“Geography of Claudius Ptolemy” by Claudius Ptolemy , Edward Luther Stevenson, et al. | (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Geography: The Discovery of the World in Classical Greece and Rome” (2017)

by Duane W. Roller Amazon.com;

“Atlas of the Roman World” by (1981) Amazon.com

“Strabo's Geography: A Translation for the Modern World”

by Strabo, translated by Sarah Pothecary Amazon.com;

“Delphi Complete Works of Strabo - Geography (Illustrated)” Amazon.com;

“A Historical and Topographical Guide to the Geography of Strabo”

by Duane W. Roller (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Mediterranean” by Michael Grant (1988) Amazon.com;

Boundaries and Divisions of Italy

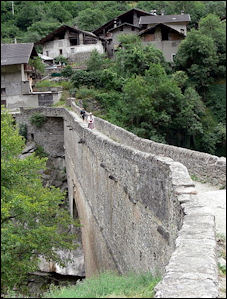

aqueduct through the countryside In very early times, the name “Italy” was applied only to the very southern part of the peninsula. But from this small area it was extended so as to cover the whole peninsula which actually projects into the sea, and finally the whole territory south of the Alps. The peninsula is washed on the east by the Adriatic or Upper Sea, and on the west by the Tyrrhenian or Lower Sea. Italy lies for the most part between the parallels of thirty-eight degrees and forty-six degrees north latitude. It has a length of about 720 miles; a width varying from 330 to 100 miles; and an area of about 91,000 square miles. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Ancient Italy is generally divided Italy into three divisions: northern, central, and southern. 1) Northern Italy comprised the whole continental portion from the Alps to a line drawn from the river Macra on the west to the Rubicon on the east. It contained three distinct countries: Liguria toward the west, Cisalpine Gaul in the center, and Venetia toward the east. 2) Southern Italy comprised the rest of the peninsula and contained four countries, namely, two on the western coast, Lucania and Bruttium, extending into the toe of Italy; and two on the eastern coast, Apulia and Calabria (or Iapygia), extending into the heel of Italy. \~\

3) Central Italy comprised the northern part of the peninsula proper, that is, the territory between the line just drawn from the Macra to the Rubicon, and another line drawn from the Silarus on the west to the Frento on the east. This territory contained six countries, namely, three on the western coast,—Etruria, Latium (la'shi-um), and Campania; and three on the eastern coast and along the Apennines,—Umbria, Picenum, and what we call the Sabellian country, which included many mountain tribes, chief among which were the Sabines, the Frentani, and the Samnites. \~\

Mountains and Rivers of Italy

There are two famous mountain chains which belong to Italy, the Alps and the Apennines. 1) The Alps form a semicircular boundary on the north and afford a formidable barrier against the neighboring countries of Europe. Starting from the sea at its western extremity, this chain stretches toward the north for about 150 miles, when it rises in the lofty peak of Mt. Blanc, 15,000 feet in height; and then continues its course in an easterly direction for about 330 miles, approaching the head of the Adriatic Sea, and disappearing along its coast. It is crossed by several passes, through which foreign peoples have sometimes found their way into the peninsula. 2) The Apennines, beginning at the western extremity of the Alps, extend through the whole length of the peninsula, forming the backbone of Italy. From this main line are thrown off numerous spurs and scattered peaks. Sometimes the Apennines have furnished to Rome a kind of barrier against invaders from the north. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901 \~]

“The most important river of Italy is the Po, which, with its hundred tributaries, drains the fertile valley in the north, lying between the Alps and the Apennines. The eastern slope of the peninsula proper is drained by a large number of streams, the most noted of which are the Rubicon, the Metaurus, the Frento, and the Aufidus. On the western slope the most important river is the Tiber, with its tributary, the Anio. \~\

Roman Provinces

Chief Roman Provinces (with dates of their acquisition or organization): Total, 32. Many of the main provinces were subdivided into smaller provinces, each under a separate governor—making the total number of provincial governors more than one hundred. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

EUROPEAN PROVINCES

1) Western.

Spain (205-19 B.C.).

Gaul (France, 120-17 B.C.).

Britain (A.D. 43-84).

2) Central.

Rhaetia et Vindelicia (roughly Switzerland, northern Italy15 B.C.).

Noricum (Austria, Slovenia, 15 B.C.).

Pannonia (western Hungary, eastern Austria, northern Croatia, north-western Serbia, northern Slovenia, western Slovakia and northern Bosnia and Herzegovina. A.D. 10).

3) Eastern.

Illyricum (northern Albania, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina and coastal Croatia, 167-59 B.C.).

Macedonia (northern Greece, modern Macedonia, 146 B.C.).

Achaia (western Greece, 146 B.C.).

Moesia (Central Serbia, Kosovo, northern modern Macedonia, northern Bulgaria and Romanian Dobrudja 20 B.C.).

Thrace (northeast Greece, A.D. 40).

Dacia (Romania, A.D. 107). \~\

AFRICAN PROVINCES

Africa proper (Libya, former Carthage, 146 B.C.).

Cyrenaica and Crete (74, 63 B.C.).

Numidia (Algeria, small parts of Tunisia, Libya, 46 B.C.).

Egypt (30 B.C.).

Mauretania (western Algeria, Morocco, A.D. 42). \~\

ASIATIC PROVINCES

1) In Asia Minor (Anatolia, modern Turkey)

Asia proper (western Turkey133 B.C.).

Bithynia et Pontus (northern Turkey, south of the Black Sea, 74, 65 B.C.).

Cilicia (southeast coast of Turkey, 67 B.C.).

Galatia (central Turkey, 25 B.C.).

Pamphylia et Lycia (southwest Turkey, 25, A.D. 43).

Cappadocia (eastern Turkey, A.D. 17).

2) In Southwestern Asia.

Syria (64 B.C.).

Judea (Israel, 63 - A.D. 70).

Arabia Petraea (A.D. 105).

Armenia (A.D. 114).

Mesopotamia (A.D. 115).

Assyria (A.D. 115). \~\

ISLAND PROVINCES

Sicily (241 B.C.).

Sardinia et Corsica (238 B.C.).

Cyprus (58 B.C.). \~\

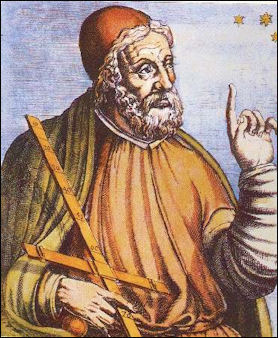

Ptolemy, Geography and the Earth at the Center of the Universe

Ptolemy Claudius Ptolemaeus , Ptolemy for short, was a Greco-Roman astronomer and mathematician of the 2nd century A.D. The exact dates of his life are unknown, but he is believed to have worked in Alexandria between A.D. 127 and 148 since some of his astronomical observations are consistent with those dates. Ptolemy combined centuries of Greek learning with 14 years of observations of the stars and planets to produce “ Geography” (A.D. 141), which declared that the Earth was at the center of the universe and used this theory to explain and predict the positions of stars and planets. Ptolemy is regarded as the father of modern geography. He also wrote about music, optics, kings, chronology and astrology, but he is remembered most for his assertion the Earth was the center of the universe.

Bill Thayer of the University of Chicago wrote: ““Ptolemy's most famous works are the Almagest, a 13 book textbook of astronomy in which among many other things, he lays the foundations of modern trigonometry; the Tetrabiblos, a compendium of astrology; and the Geography. He also wrote many other works centered on applied mathematics: astronomy, optics, music, etc.; a small Canon of Latitudes and Longitudes may be his as well: it is a sort of abridged version of the Geography, although the coördinates for certain places are not the same — manuscript transmission problems, maybe. It is sad that, as with so many figures of Antiquity, we know next to nothing about the man himself. [Source: Bill Thayer of the University of Chicago , Lacus Curtius]

Ptolemy wrote "Geography looks at the position rather than quality, noting the relation of distances everywhere, and emulating the art of painting only in some of its major description.” Ptolemy's system of latitude and longitude used lines that were a uniform distance apart and were represented with curved lines to compensate for the spherical shape of the Earth. The first longitude were not equally spaced apart like those today; they ran through well known places like Alexandria, Rhodes, the Pillars of Hercules and the mouth of the Persian Gulf. Ptolemy improved this system. However he grossly underestimated the circumference of the Earth. He declared it to be 18,000 miles (as opposed to the true figure of about 24,586 miles)

Ptolemy may have also been the one who invented the words "longitude" and "latitude." The principals he laid out in “ Geography” were the basis for the knowledge of geography, maps and atlases in Europe until the 17th century. Barthalamule Dias and Vasco de Gama had sailed around the Cape of Good Hope of southern Africa maps based on Ptolemy's view of the world showed the Indian Ocean to be as land bound as the Mediterranean Sea. His erroneous calculation of the circumference of the Earth was one reason why Columbus decided to sail of to India across the Atlantic (based on Ptolemy's calculations Columbus thought that Asia was closer than it is really was). [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin,∞]

Ptolemy's system endured for more than 1,400 years (until Copernicus), partly because the Roman Catholic Church liked "the human-centered view of the world." Ptolemy was ignored during the Middle Ages and many says his revival in the Renaissance is once of the forces that spurred thinking about man’s place in the world and the universe. Even though the Greeks had figured out the Earth was round, the Christians put forth the idea that seas were probably unnavigable, and if they were navigable, one should not venture too close to paradise which was not to far away.∞

Strabo (born 63 B.C.) produced maps of the Roman Empire, then the known world. He called the Atlantic the “continuous sea” in his “ Geography” . The famous Farnese Atlas is a globe found at Pompeii that showed the Roman constellations.

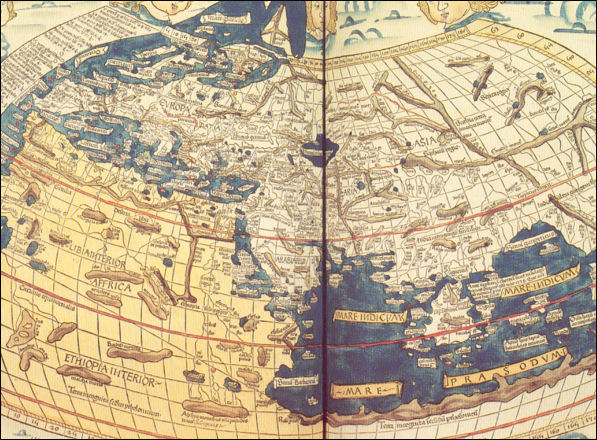

Ptolemy's Geography

Ptolemy

Bill Thayer of the University of Chicago wrote: “Ptolemy's Geography was what we would now call an atlas, the core of which were of course the maps, referred to in the text and table of contents below as "Fifth Map of Europe", "Third Map of Asia", etc. The manual copying of maps is fiendish work, however, and considerably less reliable than that of text — Ptolemy was well aware of this (Book I, Chapter 18) — and his maps have consequently disappeared: nothing remains but the index. Recognizing that the maps would be a sticking point, Ptolemy also suggested that people replot his data, and a good section of Book I of the Geography offers advice on how to draw the maps. [Source: Bill Thayer of the University of Chicago , Lacus Curtius]

“Ptolemy's coördinates are in degrees and minutes (360 degrees to a circle, 60 minutes to a degree), just like our own. His North-South coördinates (latitudes) are measured like our own from the Equator. His East-West coördinates (longitudes) are measured eastward from a point somewhere W of the westernmost point he catalogues in the Geography, traditionally read as "east of the Blessed Isles": for that reason, in this Web edition I indicated latitudes with the familiar degree sign (e.g., 5°00N), but his longitudes with an asterisk instead (e.g., 25*00).

“Various people at various times have redrawn the maps from the coördinates given in the work: the map appended to Prof. Stevenson's edition, for example, is a medieval version or copy of just such a replot, but both Planudes and Karl Müller have done it as well. Thus, in undertaking this Web edition at the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, I found myself very moved to be, and in good company at that, following Claudius Ptolemy's instructions using instruments he would never have dreamt of: every once in a while, this would hit me for a few seconds and make the unspeakably tedious cartographic reproduction much easier.

Book 2

1 Hibernia island of Britannia - First Map of Europe

2 Albion island of Britannia - First Map of Europe

3 Hispanic Baetica - Second Map of Europe

4 Hispanic Lusitania - Second Map of Europe

5 Hispanic Tarraconensis - Second Map of Europe

6 Aquitanian Gaul - Third Map of Europe

7 Lugdunensian Gaul - Third Map of Europe

8 Belgic Gaul - Third Map of Europe

9 Narbonensian Gaul - Third Map of Europe

10 Greater Germania - Fourth Map of Europe

11 Raetia and Vindelica - Fifth Map of Europe

12 Noricum - Fifth Map of Europe

13 Upper Pannonia - Fifth Map of Europe

14 Lower Pannonia - Fifth Map of Europe

15 Illyria or Liburnia and Dalmatia - Fifth Map of Europe

15 Provinces • 5 Maps

Book 3

1 All Italy - Sixth Map of Europe

2 Corsica island - Sixth Map of Europe

3 Sardinia island - Seventh Map of Europe

4 Sicily island - Seventh Map of Europe

5 Sarmatian Europe - Eighth Map of Europe

6 Tauric peninsula - Eighth Map of Europe

7 Iazyges Metanastae - Ninth Map of Europe

8 Dacia - Ninth Map of Europe

9 Upper Moesia - Ninth Map of Europe

10 Lower Moesia - Ninth Map of Europe

11 Thracia and the Peninsula - Ninth Map of Europe

12 Macedonia - Tenth Map of Europe

13 Epirus - Tenth Map of Europe

14 Achaia - Tenth Map of Europe

15 Crete island - Tenth Map of Europe

15 Provinces • 5 Maps

World of Ptolemy as shown by Johannes de Armsshein Ulm 1482

Book 4

1Mauritania Tingitana - First Map of Africa

2 Mauritania Caesariensis - First Map of Africa

3 Numidia and Africa proper - Second Map of Africa

4 Cyrenaica - Third Map of Africa

5 Marmarica, which is properly called Libya, All of Egypt, both Lower and Upper - Third Map of Africa

6 Libya Interior - Fourth Map of Africa

7 Ethiopia below Egypt - Fourth Map of Africa

8 Ethiopia in the interior below this - Fourth Map of Africa

12 Provinces • 4 Maps

Book 5

1Pontus and Bithynia - First Map of Asia

2 Asia which is properly so called - First Map of Asia

3 Lycia - First Map of Asia

4 Pamphylia - First Map of Asia

5 Galatia - First Map of Asia

6 Cappadocia - First Map of Asia

7 Cilicia - First Map of Asia

8 Asiatic Sarmatia - Second Map of Asia

9 Colchis - Third Map of Asia

10 Iberia - Third Map of Asia

11 Albania - Third Map of Asia

12 Greater Armenia - Third Map of Asia

13 Cyprus island - Fourth Map of Asia

14 Syria - Fourth Map of Asia

15 Palestine - Fourth Map of Asia

16 Arabia Petraea - Fourth Map of Asia

17 Mesopotamia - Fourth Map of Asia

18Arabia Deserta - Fourth Map of Asia

19 Babylonia - Fourth Map of Asia

19 Provinces • 4 Maps

Huge 2nd Century Map of Rome

Dated to A.D. 203–211, the Forma Urbis Romae, or map of the city of Rome, was a massive plan of the layout of the city under the emperor Septimius Severus (r. A.D. 193–211). Although only a small portion of the plan survives, scholars are relatively certain it illustrated most of the city. Drawn at a scale of 1:240, the plan resembles a land surveying map, in that it includes not only streets and blocks, but also interior features of buildings, such as colonnades and staircases.

A marble fragment of this map found in Rome measures 66 by 60 centimeters (26 by 23.6 inches). According to Archaeology magazine: It shows commercial structures on the southeastern slope of the Viminal Hill. The Forma Urbis adorned the wall of a room in Rome’s Temple of Peace that might have served as an archive of maps and records.

The monumental size of the whole thing — 18 by 13 meters (60 by 43 feet) — suggests a decorative rather than practical function, says archaeologist Susann Lusnia of Tulane University. “The Forma Urbis provided an overview of the changes made to Rome by Severus in his quest for legitimacy and establishment of his dynastic succession,” she says. “The marble plan was itself a monument to the Severan legacy in Rome.” Severus’ ambitious building program included both restoration of older monuments and creation of new ones as part of his effort to draw attention to his nascent dynasty. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2019]

Weird Ancient Geography

Strabo (64 B.C.-A.D. 25) speculated the land straddling the equator was so parched by the sun only turpentine trees could grow there. The only creatures that could live in such a place, he said, would have "woolly hair, crumpled horns, protruding lips, and flat noses (for their other extremities were contorted by the heat)." In A.D. 250 Solinis described one-eyed giants that drank from human skulls and umbrella men in India who stood on one foot and put their other foot over their head to protect themselves when it rained.

Among the fantastic places described by Pliny the Elder were the Ear Islands off of Germany, where fisherman were reported to have to such large ears they wrapped their bodies with them like cloaks; Hyperborea, an island near Scotland, where the sun only set once a year, people chose the time of their death by leaping off a cliff and cliffs shaped like women came to life at night and lured ships to their doom among the rocks. In Africa he said there were snakes with heads at each end of their body and a headless tribe with eyes and lips on their chest.

Extent of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire between 218 BC and 117 AD

Lucian described a 25-mile-long island made completely of cheese and an island where women grew from vines. Travelers to the latter were warned not to have sex with these women for they might turn into vines themselves. Lucian also described an island where people could walk on water because their feet were made of cork and another island where men made oats from giant pumpkins. [Source: "Don't Know Much About Geography" by Kenneth Davis, William Morrow & Co.]

Weather in Rome and Italy

The climate of Italy varies greatly as we pass from the north to the south. In the valley of the Po the winters are often severe, and the air is chilled by the neighboring snows of the Alps. In central Italy the climate is mild and agreeable, snow being rarely seen south of the Tiber, except on the ranges of the Apennines; while in southern Italy we approach a climate almost tropical, the land being often swept by the hot south wind, the sirocco, from the plains of Africa. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

Most of Italy has four seasons, which are somewhat similar to those in the United States, and climate is generally mild, even though Italy has the same latitude as New England, thanks to the tempering effect of the Mediterranean Sea. Because Italy stretches about 750 miles from north to south there are variations in climate, ranging from tropical in southern Sicily to blustery and snowy in the Alps in northern Italy.

More rain tends to fall in the autumn, winter and spring than in the summer. And the Alps and the Dolomites receive quite a bit of snow. Temperatures are considerably cooler in the mountains and warmer along the coast. Spring is generally pleasant and sometimes rainy. Summer is dry and hot and can be very muggy and humid. Autumn is slightly rainier and has temperatures that are generally slightly warmer than in the spring. Winter varies in length and coldness depending on the region.

View of Vesuvius on a nice day

The coastal regions, southern Italy and the islands of Sardinia and Sicily, have spring- and summer-like weather throughout much of the year. The weather in these places is quite hot and sunny in the summer and varies from cool to pleasant in the winter. The mountains and northern regions have four distinct seasons with hot summers and cold winters.

Warm summers and mild winters characterize the center of the country. Sometimes, however, the weather can be surprisingly cold. It is in not unusual for temperatures to drop below freezing at night in Rome in January and for there to be temperature difference of 30̊F between night and day so bring layers of clothing if you are traveling there in the autumn, winter or spring and bundle up in he morning and shed the layers as the temperature warms. It also seems hot when the weather is sunny and cold when it us windy and cloudy.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024