Home | Category: Art and Architecture

ANCIENT GREEK ARCHITECTURE

Olympia Zeus Temple Restoration The word "architect" comes from the Greek word for master carpenter. "Tecture" means a dwelling or building. Most of the monuments and temples that remain today were made of marble or stone. In their time they were painted on the outside.

Unlike Egyptian temples which were made for a few select people to see from the inside Greek temples were constructed for everyone to enjoy from the outside. Greek architecture was oriented towards outdoor monuments and used post-and-lintel architecture while the Romans were oriented towards interior spaces, supported by Romans arches. The Greeks used the arch, but they found its shape so unappealing they used in mainly sewers. Many great works of European and American architecture are based on Greek architecture.

Greeks didn't appreciate nature for its own sake, it was something to be used. Mountains were not something to be climbed for a view, they were the home of gods, trees provided shade and plants gave food and drink. Beautiful places were often littered with shrines. Strabo wrote: "The whole tract is full of shrines to Artemis, Aphrodite, and the Nymphs...there are numerous shrines of Poseidon on the headlands by the sea."

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Ancient Greek architects strove for the precision and excellence of workmanship that are the hallmarks of Greek art in general. The formulas they invented as early as the sixth century B.C. have influenced the architecture of the past two millennia. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

According to the Canadian Museum of History: “Generally, when people speak of “Greek architecture” it is usually “public” architecture that they have in mind — temples, theatres, market-places, gymnasia, commemorative structures, and given the propensity of the ancient Greeks for war, fortifications. After all, as Plato suggested, war is the natural state of mankind. [Source: Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca |]

Websites on Ancient Greece: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; The Ancient City of Athens stoa.org/athens; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ;Ancient-Greek.org ancientgreece.com;Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Greek Architecture” (The Yale University Press Pelican History of Art)

by A. W. Lawrence (1996) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Architecture” Gene Waddell (2017) Amazon.com;

“Orders of Architecture” by R. A. Cordingley (2015) Amazon.com;

“Origins of Classical Architecture: Temples, Orders, and Gifts to the Gods in Ancient Greece” by Mark Wilson Jones (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Greek Temples” by Tony Spawforth (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Earth, the Temple, and the Gods: Greek Sacred Architecture” by Vincent Scully (1979 Amazon.com;

“Greek Sanctuaries and Temple Architecture: An Introduction” by Mary Emerson (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Optical Corrections of the Doric Temple: Form and Meaning in Greek Sacred Architecture” by Tapio Uolevi Prokkola (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Parthenon” (Wonders of the World)

by Mary Beard Amazon.com;

“The Parthenon: The Height of Greek Civilization” (Wonders of the World Book)

by Elizabeth Mann (Author), Yuan Lee (Illustrator) (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Art and Architecture of Ancient Greece: An Illustrated Account of Classical Greek Buildings, Sculptures and Paintings, Shown in 200 Glorious Photographs and Drawings” by Nigel Rodgers (2012) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Housing” by Lisa C. Nevett (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Houses: Their History and Development from the Neolithic Period to the Hellenistic Age” by Bertha Carr Rider (1964) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Houses and Households: Chronological, Regional, and Social Diversity”

by Bradley A. Ault and Lisa C. Nevett (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient City” by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges (1864) Amazon.com;

Minoan and Mycenaean Architecture, See Minoans and Mycenaeans Under History

Features of Greek Architecture

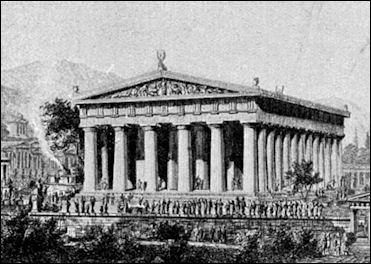

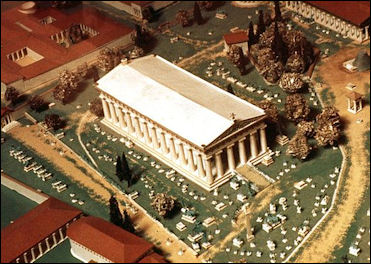

Zeus temple model Large houses, temples and tombs today have a similar plan — with a main court, hall and private rooms — as their counterparts in ancient Greece. Doric and Ionic are the two most well known styles of Greek architecture.

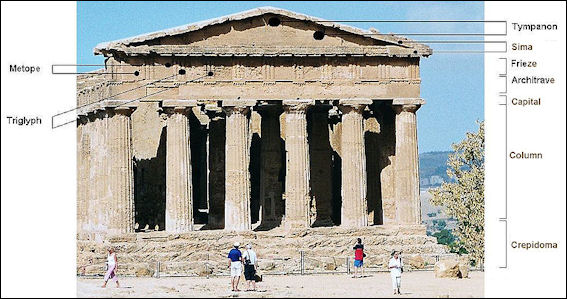

A quick review of some Greek architectural terms: As you look at the front of a Greek building the lintel is the part of the building held up by columns. The frieze is in between roof and the lintel, and it can either be filled with statues and bas-reliefs or composed of alternating trigylphs (little columnlike facades) and metopes (unornamented spaces). The long triangular part of roof above the frieze is the pediment.

Thick, muscular Doric columns have a plain and simple capital. The Parthenon is considered the quintessential Doric structure. More "feminine" Ionian columns are more slender and have declarative scroll-shaped capitals. Corinthian columns, which are an adaption of Ionian columns, have a flowery top. The side corners of the columns themselves are composed of a long shaft with a capital at the top and a base at the bottom.

As a general rule, every city was fortified with the extent and nature of the fortifications being influenced by natural landscape features. It was only a state such as Sparta, whose reputation preceded it, or a poorer community with little worth stealing that didn’t have substantial city walls. The main defensive structure was an encircling wall whose length was interrupted at strategic intervals by round or square towers. The thickness of the wall and the height, shape and placement of towers were important considerations. Usually the walls and towers were built of limestone. Vertical slits in the tower walls allowed archers to fire their arrows down upon attackers. |

History of Greek Architecture

Although nearly all forms of modern architecture can be traced back to Greek architecture no one knows how it evolved. Clay models of temples from the 8th century B.C. depict house-like buildings with steeped pitched roofs and columns only at the entrance and rear. Greek architecture developed from the wood and mud brick building of pre-classical Greece and was influenced by Egyptian architecture (columns), Minoans (column design) and Mycenaean architecture (the floor plan). The design for the Mycenaean royal hall provided the basic design on which Greek temples were based.

One of the great contributions of Greek architecture was putting sculpture and bas-reliefs on the pediments which the Mycenaeans had left empty. The Egyptian decorated some of their temples with sculpture but mostly in the form of shallow reliefs. The Greeks raised this form of expression to an artform.

Up until the 7th century B.C., Greek temples were made of wood. Stone became the building material of choice when wood columns were found to be incapable of bearing roofing tiles. Marble was most often used because it was found everywhere in Greece and Asia Minor. Most of the marble was quarried only about ten miles away from the site of the monument.μ

Doric order

From early times, the open air altar played an important role in worship. The outdoor aspect was a practical consideration. Sacrificing 100 head of oxen, as happened on festive occasions such as at the Olympic Games, with its inevitable blood and smoke, was an activity best carried out in the open air. But, influenced by the East- particularly, Egypt- temples began to be seen as appropriate structures to house the image of a deity. That usage dictated a level of quality befitting a divine being. Accordingly, the Greeks looked to their predecessors and to their neighbours for ideas on suitable designs for a temple. From their Mycenaean ancestors they took the idea of an architectural footprint based on the rectangular megaron or “great hall”- a room with a frontal porch supported by columns. From the Egyptians they borrowed the concept of monumentality and a range of design elements and ornaments such as fluted columns, palmettes, spirals, rosettes, lotus plant imagery, etc. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

“The first Greek temples were a far cry from a classical masterpiece such as the Parthenon. During the Bronze Age it seems that no temples were built and there is uncertainty as to when they began to be built. It happened during the Dark Age but surviving examples, according to A.W. Lawrence are “few in number and of deplorable quality.” The construction materials were mud brick for the walls with high-pitched roofs made of timber. Greek builders were not satisfied for long with this model and they gradually made their way to stone construction. |

“During the 7th century the Greek “Orders of Architecture” began its evolution. Few people today are not familiar with the notion that there are Doric, Ionic and Corinthian styles. Many can even pick out the different styles in modern examples in their cities for these became widely admired and copied throughout the world...The Parthenon is considered to be the greatest of the Doric temples, the ultimate achievement of architectural perfection in this style. |

“All three styles are built upon a single construction system- the post and lintel- where a horizontal block of stone (the lintel) is laid across two supports (posts or columns). It was a simple system which imposed some limitations on the architects but it assured an appropriate result. An inspired architect might produce a Parthenon but a less gifted individual would at least produce a temple adequate for religious worship. Instead of seeking innovation in other systems and styles, Greek architects sought refinement and perfection in the system that they had chosen. They laid down a framework of rules which spelled out how to address composition and proportion. All of the elements and components had a specified form and function. Tey working within that formula Greek architects were able to produce a range of distinctive temples including some that made the List of Wonders of the ancient world. |

Did Greek Architecture Really Evolve From Wood?

Jarrat A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: Architectural historians studying the period around 600 to 700 B.C. when Classical Age architecture began to evolve could draw on the works of the Roman architect Vitruvius and his De Architectura, 10 books on architectural history written at the end of the first century B.C. Vitruvius believed that certain architectural elements of the entablature — the lintel of a classical building that is supported by the columns or walls — of Doric stone buildings had evolved from wooden prototypes, as had decorative elements, such as mutules, guttae, and triglyphs. The theory of the wooden origins of the Doric order became the prevailing one. [Source: Jarrat A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2016]

The Heraion, or Temple of Hera, in Olympia, has been studied to investigate this theory. “Because the sizes of the Heraion’s columns vary — some are composed of distinct drums (the individual sections that make up the shaft of a column) stacked atop one another, while others are monolithic — and because many of its capitals are of different styles and belong to different time periods, Wilhelm Dörpfeld theorized that as the original wooden columns decayed, they were replaced with stone ones. Nineteenth-century archaeologists conjectured that little would be found of early Greek monumental architecture because it all would have disappeared and been replaced by stone — a useful explanation for why none of these wooden architectural elements did, in fact, survive. “The temple of Hera at Olympia provided the best example of an older wooden Doric architecture in the midst of the hypothesized conversion to stone,” says archaeologist Phil Sapirstein, who teaches at University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Using thousands of digital images, Sapirstein created this highly detailed and extremely accurate 3-D model of the temple of Hera, or the Heraion, at the site of Olympia. “Inspired by a long-standing interest in the Heraion, which had not been comprehensively reexamined since Dörpfeld’s publication of his work on the temple nearly a century ago, and with the success of his 3-D models in mind, Sapirstein decided it was time to take another look. “Early on in my research I saw some evidence that the Heraion’s stone columns were mostly original to the building and that the model of the wood-turned-stone columns was actually pretty dubious,” Sapirstein says.

“One of the main pieces of evidence cited to support the idea that the Doric order evolved from wooden origins is the crescent-shaped cuttings in the stylobate, the platform on which the columns sit. These cuttings were believed to have been used to facilitate the raising of wooden, rather than stone, columns. This theory, which has gone largely unquestioned for more than 80 years, has rested on century-old drawings of the Heraion’s early excavations. While cleaning the area of the stylobate where six of the columns are missing, Sapirstein realized that the cuttings actually didn’t have to have anything to do with moving wooden columns at all. “I had a eureka moment,” he says, “and it occurred to me that these crescent-shaped slots might actually be associated with lifting monolithic stone column shafts and not necessarily wooden ones. This would mean that none of the peristyle would ever have been wood. The 3-D recording was essential for revealing how all of this would have worked.”

from the Five Orders of Architecture (1889)

Doric Versus Ionic Architecture

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The two principal orders in Archaic and Classical Greek architecture are the Doric and the Ionic. In the first, the Doric order, the columns are fluted and have no base. The capitals are composed of two parts consisting of a flat slab, the abacus, and a cushion-like slab known as the echinus. On the capital rests the entablature, which is made up of three parts: the architrave, the frieze, and the cornice. The architrave is typically undecorated except for a narrow band to which are attached pegs, known as guttae. On the frieze are alternating series of triglyphs (three bars) and metopes, stone slabs frequently decorated with relief sculpture. The pediment, the triangular space enclosed by the gables at either end of the building, was often adorned with sculpture, early on in relief and later in the round. Among the best-preserved examples of Archaic Doric architecture are the temple of Apollo at Corinth, built in the second quarter of the sixth century B.C., and the temple of Aphaia at Aegina, built around 500–480 B.C. To the latter belong at least three different groups of pedimental sculpture exemplary of stylistic development between the end of the sixth century and beginning of the fifth century B.C. in Attica. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

“In the Ionic order of architecture, bases support the columns, which have more vertical flutes than those of the Doric order. Ionic capitals have two volutes that rest atop a band of palm-leaf ornaments. The abacus is narrow and the entablature, unlike that of the Doric order, usually consists of three simple horizontal bands. The most important feature of the Ionic order is the frieze, which is usually carved with relief sculpture arranged in a continuous pattern around the building. \^/

“In general, the Doric order occurs more frequently on the Greek mainland and at sites on the Italian peninsula, where there were many Greek colonies. The Ionic order was more popular among Greeks in Asia Minor and in the Greek islands. A third order of Greek architecture, known as the Corinthian, first developed in the late Classical period, but was more common in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Corinthian capitals have a bell-shaped echinus decorated with acanthus leaves, spirals, and palmettes. There is also a pair of small volutes at each corner; thus, the capital provides the same view from all sides. “The architectural order governed not only the column, but also the relationships among all the components of architecture. As a result, every piece of a Greek building is integral to its overall structure; a fragment of molding often can be used to reconstruct an entire building. \^/

Greek Versus Roman Architecture

Some say that the Romans took Etruscan elements — the high podium and columns arranged in a semicircle — and incorporated them with Greek temple architecture. Roman temples were more spacious than their Greek counterparts because unlike the Greeks, who displayed only a statue of the god the temple was built for, the Roman needed room for their statues and weapons they took as trophies from the people they conquered.

One of the main differences between Greek and Roman architecture was that the Greek buildings were intended to be viewed from the outside and Romans created huge indoor spaces that were put to many uses. Greek temples were essentially a roof with forest of columns underneath it that were necessary to support it. They had nevr learned to develop the arch, dome or vaults to great level of sophistication. The Romans used these three elements of architecture to construct all sorts of different kinds of structures: baths, aqueducts, basilicas, etc. The curve was the essential feature: "walls became ceilings, ceilings reached up to the heavens." ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

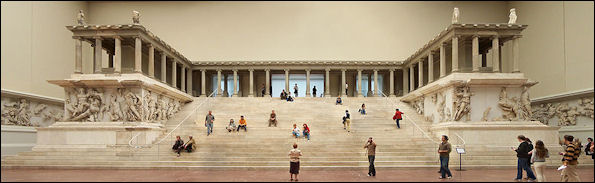

Altar of Zeus from Pergamon, Turkey

The Greeks depended on post-and-lintel architecture while the Romans used the arch. The arch helped the Romans construct larger interior spaces. If the Pantheon was built using Greek methods the large open space inside would have been overcrowded with columns.

Ancient Greek Temples

Ancient Greek temples, unlike churches, were places the gods lived, not houses of worship. They were regarded as the home of cult statues and places where people could pay homage to gods and leave gifts for them. Some were only entered once or twice a year, and then only by the priest of the temple. Temples were built on hills, known as acropolises, apparently to impress outsiders coming to the city.

Greek temples were constructed to be admired from the outside. Ordinary people were often not allowed to go inside and if they were there usually wasn't much for them to see except for a large statue of the god the temple honored. On the outside statues were placed in niches. In a couple of instances the columns themselves were made into statues of women.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The Greeks worshipped in sanctuaries located, according to the nature of the particular deity, either within the city or in the countryside. A sanctuary was a well-defined sacred space set apart usually by an enclosure wall. This sacred precinct, also known as a temenos, contained the temple with a monumental cult image of the deity, an outdoor altar, statues and votive offerings to the gods, and often features of landscape such as sacred trees or springs. Many temples benefited from their natural surroundings, which helped to express the character of the divinities. For instance, the temple at Sounion dedicated to Poseidon, god of the sea, commands a spectacular view of the water on three sides, and the Parthenon on the rocky Athenian Akropolis celebrates the indomitable might of the goddess Athena. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

See Separate Articles: ANCIENT GREEK TEMPLES, SANCTUARIES AND SACRED PLACES europe.factsanddetails.com ; ACROPOLIS AND TEMPLES IN ANCIENT ATHENS europe.factsanddetails.com PARTHENON: ITS HISTORY, ARCHITECTURE AND SCULPTURES europe.factsanddetails.com

Temple features

Ancient Greek Temple Construction

Ancient Greek temples were designed and constructed by craftsmen and decisions about column size and their location, it appears, were made when the building was being erected. According to Boorstin "scholars have not found a single architectural drawing." Most temples had a similar design and really the only creative work done by the architects was the artwork on the friezes and lintels. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,"]

To construct a temple, Greek builders used ropes, pulleys and wooden cranes, as high as 80 feet tall, and sometimes used 25-foot-tall teamons, statues of a giant used as a support. Rough limestone columns were lifted and placed and then fluted by a stone cutter.

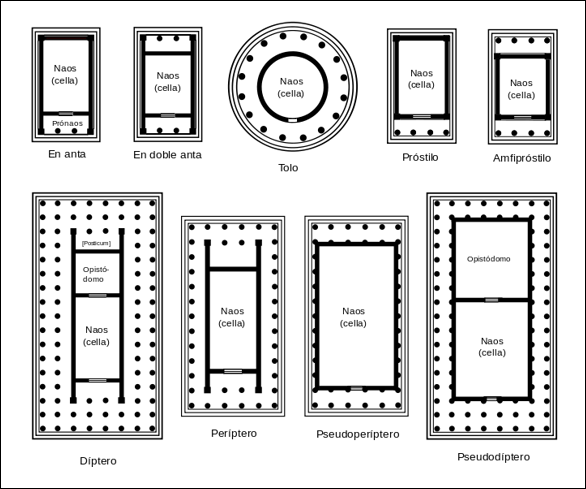

“According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Although the ancient Greeks erected buildings of many types, the Greek temple best exemplifies the aims and methods of Greek architecture. The temple typically incorporated an oblong plan, and one or more rows of columns surrounding all four sides. The vertical structure of the temple conformed to an order, a fixed arrangement of forms unified by principles of symmetry and harmony. There was usually a pronaos (front porch) and an opisthodomos (back porch). The upper elements of the temple were usually made of mudbrick and timber, and the platform of the building was of cut masonry. Columns were carved of local stone, usually limestone or tufa; in much earlier temples, columns would have been made of wood. Marble was used in many temples, such as the Parthenon in Athens, which is decorated with Pentelic marble and marble from the Cycladic island of Paros. The interior of the Greek temple characteristically consisted of a cella, the inner shrine in which stood the cult statue, and sometimes one or two antechambers, in which were stored the treasury with votive offerings. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

Theaters in Ancient Greece

According to the Canadian Museum of History: “In the fourth century B.C. cities began to build stone theatres. In fact one of the most characteristic buildings found in any ancient Greek city of any importance was a quality theatre. Audiences in Athens who had attended presentations by the masters of the Greek stage- Sophocles, Aeschylus and Euripides- had been seated on wooden benches lining the south slope of the Acropolis. Their descendants had a better environment. The typical Greek theatre was built into the slope of a hillside which provided support for the curving banks of stone seats that faced the stage. Most patrons brought their own seat cushions to these open air structures since watching plays during a festival period was somewhat of an endurance contest. [Source: Canadian Museum of History ]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The Greek theater consisted essentially of the orchestra, the flat dancing floor of the chorus, and the theatron, the actual structure of the theater building. Since theaters in antiquity were frequently modified and rebuilt, the surviving remains offer little clear evidence of the nature of the theatrical space available to the Classical dramatists in the sixth and fifth centuries B.C. There is no physical evidence for a circular orchestra earlier than that of the great theater at Epidauros dated to around 330 B.C.” [Source: Colette Hemingway, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org]

“Most likely, the audience in fifth-century B.C. Athens was seated close to the stage in a rectilinear arrangement, such as appears at the well-preserved theater at Thorikos in Attica. During this early period in Greek drama, the stage and most probably the skene (stage building) were made of wood. Vase paintings depicting Greek comedy from the late fifth and early fourth centuries B.C. suggest that the stage stood about a meter high with a flight of steps in the center. The actors entered from either side and from a central door in the skene, which also housed the ekkyklema, a wheeled platform with sets of scenes. A mechane, or crane, located at the right end of the stage, was used to hoist gods and heroes through the air onto the stage. Greek dramatists surely made the most of the extreme contrasts between the gods up high and the actors on stage, and between the dark interior of the stage building and the bright daylight.” \^/

RELATED ARTICLE: THEATERS IN ANCIENT GREECE: STRUCTURES, STAGES, SETS, MACHINES europe.factsanddetails.com

Greek temple plans

Gymnasiums and Hippodromes

A typical Greek gymnasium was an open court surrounded by columns with areas for running, jumping and throwing and a covered area for wrestling and bathing. Young men often spent a greater part of their day in the gymnasium, occupying themselves as much with chatting and hanging out as working out. It is no surprise that Sophists conducted their first meetings in gymnasiums and Plato set up his Academy and Aristotle set up his Lyceum next to gymnasiums.

Chariot and horse races were held in long, narrow Hippodromes that seated up to 45,000 spectators. The track was not like a modern horse racing track. It was more like an oval football field with a row of columns down the middle, which created a lot of maneuvering room.

Seven Wonders of the World in Greece

The Seven Wonders of the World were first mentioned in the 2nd century B.C. by a man called Antipater of Sidon. They are: 1) the Pyramids of Giza (Egypt); 2) Hanging Gardens of Babylon (Iraq); 3) the Tomb of King Mausolus (Turkey); 4) Temple of Diana (Turkey); 5) Colossus of Rhodes (Greece); 6) Statue of Olympia (Greece); 7) The Pharos of Alexandria (Egypt).

The Seven Wonders of the World in ancient Greece and Greek Asia Minor were: 1) the Tomb of King Mausolus (Turkey); 2) Temple of Diana (Turkey); 3) Colossus of Rhodes (Greece); 4) Statue of Olympia (Greece).

Why seven? Even in ancient times, the number seven was believed to have had mystical significance and bring good. That is also why there were seven seas, seven deadly sins and seven early churches of Christendom. In ancient times, there were different lists of seven wonders and people visited the “wonders” like modern-day tourists.

The pyramids are the only one of the seven wonders still standing. Part of the Temple of Diana remains. The others vanished after they were toppled by earthquakes and/or scavenged for building material. The images that we have of the seven wonders today are primarily paintings and drawing made by medieval and Renaissance artists over a thousand years after the wonders were gone.

See Separate Article: SEVEN WONDERS OF THE WORLD europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024