Home | Category: Art and Architecture

EARLY ANCIENT GREEK SCULPTURE

Kore

The first Greek statues were made during the Archaic Age (750 B.C. to 500 B.C.). They had the same rigidity, stiff posture and stylized walking gait as their counterparts in Egypt. Their left arm was forward and the fist were clenched like most Egyptian standing figures. The first advancement the Greeks made was creating a free standing statue. Egyptian statues were either seated or shown emerging from a slab of stone which acted to hold the figure up.

Early statues called “ kouroi” were often sensuous and monumental nude statues and often featured a mysterious Mona Lisa smile. “Kouros” and “ kore” are the male and female terms for "young person." Art historian Andre Stewart told National Geographic, kouroi "were intended be erotic." The subjects were usually young, male and had beautiful bodies. The largest known kouri are 16 feet high and made from marble. Before kouri the largest known sculpture in Greece were small bronzes.

Adam Masterman, an art teacher, wrote in Quora.com: The Archaic period (700-490 B.C.) represents the Greek response to seeing the awesome and impressive monumental sculptures of ancient Egypt. Archaic sculptures are relatively realistic, but very stiff and formal. They often stand in perfectly symmetrical poses, and have an imposing bulk to their proportions. They tend to feel more like archetypes than individuals, monuments rather than portraits.”

Life-sized or larger stone sculptures were not produced in Greece before 650 B.C. It was around that time that the Egyptian pharaoh Psammetichos allowed two groups of Greeks (Ionians and Carians) to settle along the banks of the Nile River. The Greeks learned the art of large stone carving from the Egyptians although they used the limestone and marble available in Greece, not the harder porphyry and granodiorite favoured by the Egyptians. The Egyptian “look and feel” was initially adopted by the Greeks but they were not content for long to simply produce sculptures in a style that had served the East for many generations. Within a couple of centuries they had evolved their distinctive Greek approach and abandoned the Egyptian formula. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: Statues of gods featured prominently throughout the ancient world, but many of those that are best known from literary evidence have never been found. These include the nearly 40-foot-tall ivory and gold statue of the Greek goddess Athena that once stood at the back of the Parthenon.[Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine November/December 2023]

Websites on Ancient Greece: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; The Ancient City of Athens stoa.org/athens; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ;Ancient-Greek.org ancientgreece.com;Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“An Introduction to Greek Art: Sculpture and Vase Painting in the Archaic and Classical Periods” by Susan Woodford by Susan Woodford (1986, 2015) Amazon.com;

“Understanding Greek Sculpture: Ancient Meanings, Modern Readings”

by Nigel Spivey (1996) Amazon.com;

“Greek Sculpture” by John Boardman (1978) Amazon.com;

“Parthenon Sculptures” by Ian Jenkins Amazon.com;

“How to Read Greek Sculpture” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) by Sean Hemingway (2021) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Sculpture: An Image Archive for Artists and Designers” by Kale James Amazon.com;

“The Interpretation of Architectural Sculpture in Greece and Rome” by Diana Buitron-Oliver (1997) Amazon.com;

“A Manual of Ancient Sculpture, Egyptian – Assyrian – Greek – Roman: With One Hundred and Sixty Illustrations” by George Redford (2021) Amazon.com;

“Looking at Greek and Roman Sculpture in Stone: A Guide to Terms, Styles, and Techniques” by Janet Grossman (2003) Amazon.com;

“Textiles in Ancient Mediterranean Iconography” by Susanna Harris, Cecilie Brøns, Marta Zuchowska Amazon.com;

“Defining Beauty: the Body in Ancient Greek Art: Art and Thought in Ancient Greece”

by Ian Jenkins (2015) Amazon.com;

“Esthetic Basis of Greek Art” by Rhys Carpenter (1921) Amazon.com;

“Hellenistic Sculpture” (World of Art) by R. R. R. Smith (1991) Amazon.com;

“Greek Sculpture. Function, Materials, and Techniques in the Archaic and Classical Periods” by Olga Palagia, editor (Cambridge University Press, 2006); Amazon.com;

“The Technique of Greek Sculpture in the Archaic and Classical Periods” by Sheila Adam (1966) Amazon.com;

“The Emergence of the Classical Style in Greek Sculpture” by Richard T. Neer (2013) Amazon.com;

“Classical Art: From Greece to Rome (Oxford History of Art) by Mary Beard, John Henderson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

“Greek Art” (World of Art) by John Boardman (1964) Amazon.com;

“Archaic and Classical Greek Art” (Oxford History of Art) by Robin Osborne (1998) Amazon.com;

“Hellenistic Art: From Alexander the Great to Augustus” by Lucilla Burn (2005) Amazon.com;

Classical Greek Sculpture

Elgin Marbles part of the Cavalcade frieze from the Parthenon

Classical Greek Sculpture (500B.C. to 323 B.C.) was less rigid than sculptures from the Archaic period. Works featured flexed knees, turned heads, and contemplative expressions that were regarded as attempts to suggest motion, thoughts and naturalism. As time went on more and more anatomical features emerged, the bodies became more relaxed, muscular, sensual and less rigid, hair falls more naturally, motion was conveyed, clothing seems softer and more cloth-like facial expression convey more emotion and movement and action and are more realistically conveyed. A "middle distance" gaze of the statue’s eyes was greatly admired.

As Greek art developed and the sculptors evolved from skilled craftsmen into artists, the buttocks on their creations became more rounded, the ears took on more of a three-dimensional shape, collarbones were more pronounced, and, according to Boorstin, the lachrymal caruncle of the eyes was revealed for the first time. "The whole figure becomes more alive," he says, "as the stance becomes relaxed and rigid symmetry and posture disappears...Their favored sculptural material was bronze...Bronze freed the sculptor to uplift limbs and tempted him to new postures." [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Adam Masterman wrote in Quora.com: “The Classical period (480-323 B.C.) was defined by a marked increase in naturalism, which means that the sculptures started looking more like real people in real poses. This period shows the first examples of contrapposto, which is where the weight is shifted to one leg (which is how humans tend to stand). Contrapposto is more realistic, and it’s also more visually dynamic; it creates a subtle s-shape to the torso that is very common and recognizable in Classical sculpture. These figures are still very idealized, but with more anatomical subtlety and muscular definition, and a broadening range of poses.”

Describing a classical Nike, or Victory, from the Acropolis Museum Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times: “Bending to untie her sandal, the intricate, looping folds of her drapery creating a linear pattern that reveals rather than hides the swelling contours of her torso. Her sensuality stands in dramatic contrast to a stele from the Metropolitan's own collection, in which a mournful looking little girl holds two pet doves, one of which gently touches her mouth with its beak.” [Source: Holland Cotter, New York Times, March 12, 1993]

On some funerary sculptures, some of which may have been carved by artists who worked on the Parthenon, Cotter wrote in the New York Times: “Here the figures are neither gods nor heroes but human beings engaged in the intimate activities of their lives. On one memorial, a husband and wife gaze confidingly at each other; on another, the well-known "Grave Stele of Hegeso," a wealthy woman regretfully admires her jewels, carried in a box by her servant. The presence of the servant... is of much interest here. Notably smaller than her seated mistress, anonymous, proferring wealth that is not hers, surely she has something pertinent to say about what democracy... actually meant in the Greece of the fifth century B.C. "Golden Age," a society, after all, that held a large population of slaves and extended full citizenship only to men.

Polyclitus and Praxiteles

Polyclitus was one of Greece's most famous sculptures. According to an often repeated tale he once made two statues at the same time. One was made according to his principals of art and another he modified according the wishes of people who observed it. When the two were finally unveiled everyone marveled at one of the statues and laughed at the other. Thereupon Plyclitus said: "But the one of which you find fault with, you made yourselves; while he one you marvel at, I made." [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Polyclitus produced wonderful sculptures of athletes. A New York Times critic Grace Gluek wrote his “brilliance is evident on the rhythmic play between the torso and the thorax, each tilting slightly in the opposite directions, and in the lifelike separation of the feet that gives the otherwise placid statue a sense of movement.”

Phidias showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to His Friends by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Praxiteles did some of the most wonderful sculptures in Olympia and is one of the few artists we know by name who has produced works that exist today; the sensuous “ Aphrodite of the Cnidians” and classic “ Hermes “ . Scopas was the name of another great Greek sculptor.

On a famous story about Praxiteles, Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “ Leading from the prytaneum is a road called Tripods. The place takes its name from the shrines, large enough to hold the tripods which stand upon them, of bronze, but containing very remarkable works of art, including a Satyr, of which Praxiteles is said to have been very proud. Phryne once asked of him the most beautiful of his works, and the story goes that lover-like he agreed to give it, but refused to say which he thought the most beautiful. So a slave of Phryne rushed in saying that a fire had broken out in the studio of Praxiteles, and the greater number of his works were lost, though not all were destroyed. Praxiteles at once started to rush through the door crying that his labour was all wasted if indeed the flames had caught his Satyr and his Love. But Phryne bade him stay and be of good courage, for he had suffered no grievous loss, but had been trapped into confessing which were the most beautiful of his works. So Phryne chose the statue of Love; while a Satyr is in the temple of Dionysus hard by, a boy holding out a cup.” [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

Phidias

Phidias (or Pheidias, c. 480 – 430 BC) was a Greek sculptor, painter, and architect. His statue of Zeus at Olympia was one of the Seven Wonders of the World. He also designed the statues of the goddess Athena on the Athenian Acropolis, namely the Athena Parthenos inside the Parthenon, and the Athena Promachos, a colossal bronze which stood between it and the Propylaea, a monumental gateway that served as the entrance to the Acropolis in Athens. He is often credited as the main instigator of the Classical Greek sculptural design. Today, most critics and historians consider him one of the greatest of all ancient Greek sculptors. + [Source: Wikipedia +]

Phidias is credited with making the sculptures on the Parthenon, including the Elgin Marbles now in the British Museum, and the ivory and gold statue that was once inside, but we don't know whether he sculpted these pieces himself or was a supervisor. His skill was greatly admired and it was said he alone among mortals had seen the gods as they truly are.

Details of Phidias’s early life are minimal. Born in Athens around 500 B.C., he was the son of Charmides of Athens and likely fought in the battle of Salamis or Plataea against the Persians.The ancients believed that his masters were Hegias and Ageladas. His military service gained the favor of Cimon, a wealthy Athenian politician and military man who chose Phidias to build the memorial for the victory of Marathon at Delphi. Phidias’s reputation spread throughout Greece, and he was awarded many projects before his commission at Olympia. [Source: Mireia Movellán Luis, National Geographic History, December 15, 2023]

Phidias was involved in several scandals. Plutarch discusses Phidias' friendship with the Greek statesman Pericles and describes how enemies of Pericles tried to attack him through Phidias - who was accused of stealing gold intended for the Parthenon's statue of Athena, and of impiously portraying himself and Pericles on the shield of the statue. Phidias was also deeply in love with Pantarkes, a young boy from Elis, and carved his portrait at the foot of the Olympian Zeus

In 432 B.C., Phidias was arrested and convicted of sacrilege and "misappropriation of public funds" for carving an images of himself and his patron Pericles onto Athena's shield in the Parthenon. According to conflicting accounts, Phidias was either exiled or died in prison. See Parthenon, Athens

Lysippus

Alexander, a copy of Lysippos' piece

Lysippus is considered one of the finest sculptors of ancient Greece. Born around 390 B.C. near Corinth in a town called Sikyon, he is the only known portraitist of Alexander the Great who worked in his time. His portraits of Alexander the Great beginning when Alexander was only a small boy "were said to record the development of both a great artist and a great subject." Lysippus is also referred to as the inventor of portraiture. Portraits were a new idea to the Greeks and he was believed to be first sculpture to pour wax into his plaster mold to get the facial features right. Before him most Greek sculpture attempted only to create the most beautiful and idolized sculptures possible. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Lysippus is said to have made 1,500 statues, including portraits of Alexander the Great and Hercules and is said to have been the teacher of Chares of Lindos, the creator of the Colossus of Rhodes, one of the Seven Wonders of the World. None or few of Lysippus’s original works have been preserved. All we have today are copies of his works.

According to ancient chroniclers Lysippus worked until he was 80 and produced a great number of works in both marble and bronze. Most of what we know about his body of work has been gleaned from copies of his works and representations on coins.

Bronze Statue by Lysippus

A life-size bronze figure called “Victorious Youth,” attributed to Lysippus was snagged by fishermen in their trawling net in 1964 and was sold by the fishermen for a few hundred dollars without knowing its worth to the Barbetti brothers and smuggled out of Italy and showed in London 1971 where it was purchased by a European art consortium called Artemis. After lengthy negotiations it was purchased by the Getty Foundation and is now on display at the Getty Museum in Malibu. [Source: Los Angeles Times, July 2006]

The statue, which depicts a young athlete, is rare find in that it is one of the few existing Greek bronzes ever found and if it is indeed by Lysippus it is one of the greatest art and archeological finds ever. On top of that it is quite beautiful and displays great artistic skill. German art dealer Heinz Herzer told the Los Angeles Times, “the statues’s pose, with its hand’s poised centimeters away from its head, moments after donning the victor’s wreath...indicates great technical skill.” Remnants of flax found in its core suggest that it was made in the ancient city of Olympia. Some experts, including British archeologist Bernard Ashmle, have said that the statue is perhaps one Lysippus is said to have made of Olympic victors but proving it was made by him is difficult.

What had happened to the statue between the time the Barbetti brothers held it and its appearance in London is not known, In the 1966 the Barbettis were sentenced to four months in jail and a priest that helped them was given two months but the convictions were overturned on the grounds that the statue was found in international waters. The Italian government has demanded that the Getty museum return the statue. The Getty museum has responded by saying it was “not realistic for Italy to expect the statue to be returned, siting among other things that the statue of limitation for the claim had expired.

Masterpieces from the Classical Age

Statues in the Parthenon were heroically-scaled and meant to be seen at a distance. Unfortunately only bits and fragments of them remain. Inside the temple there was a gold and ivory statue of Athena (now gone), dully armed and wearing a triple-crested helmet. Phidias, a friend of Pericles regarded as the sculptor of the gods, sculpted the statue of Athena, the Frieze on the Parthenon and the ivory-and-gold statue of Zeus, at Olympia, one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

Most the sculptures in the Acropolis Museum were taken from buildings on the Acropolis other than the Parthenon. The most famous are the Caryatides of the Erechtheum, columns shaped like women that are known for their "archaic smiles." The other sculptures and reliefs don't look like that much at first but use your imagination. One of the more interesting ones shows Typhon, a monster with three human heads, watching a battle between Triton, a male mermaid who was the son of Poseidon, and Hercules. Another shows Athena taking on several giants. The museum also contains the exquisite statues of the enchanting doll-like “Kore in Dirian Peplos” with her falling hair. The “Kore “ from Chios retains some the original green paint and has a soothing sensual smile.

Zeus Statue at Olympia Zeus Temple

Statue of Zeus at Olympia

Reputed to be 12.2 meters (40 feet) high and placed in the great temple of Zeus in 457 B.C., the Statue of Zeus at Olympia depicted Zeus seated on a throne. His body was carved from ivory and his robe and ornaments were made of gold. It was sculpted by Phidias (who created a similar statue of Athena in the Parthenon in Athens) sometime after 432 B.C. The statue was so large that, according to the geographer Strabo, if Zeus stood up, his head would go through the roof. The craftsmanship was incredibly detailed, with intricate carvings and embellishments, including precious gemstones for his eyes. The gargantuan statue awed the ancient world for eight centuries and then disappeared — what happened to it is still not known. [Source: Mireia Movellán Luis, National Geographic History, December 15, 2023]

The statue of Zeus was made of gold and ivory plates placed over a wood structure (making it from bronze and gold would have been too heavy for a statue of this size). A system of pipes was devised to bring oil to the wood to prevent it from rotting, The oil also helped preserve the ivory. Zeus sat on the golden throne with jewels for eyes, with his feet resting on a foot stool of gold. Worshippers used to pray at the statue’s feet. Chroniclers said the statue was still there in the 2nd century B.C. After that it disappeared, most likely it was stripped and looted.

The original Temple of Zeus was destroyed in A.D. 426. The new temple one that housed the statue was 32 meters wide, 75 meters long and and 12 meters high, It was made of the finest marble and topped by a gilded statue of Nike. Sculpted lion heads with their mouths open served as drain spouts for the Temple of Zeus roof.

See Separate Article: OLYMPIA: TEMPLES, LAYOUT AND THE STATUE OF ZEUS europe.factsanddetails.com

Friezes at the Parthenon and the Elgin Marbles

The magnificent friezes on the Parthenon looped for 175 meters around the entire edifice. They show a procession of gods honoring Athena. Fragments from the eastern gable of the temple depict the birth of Athena from Zeus's head. Those on the western gable show the contest between Athena and Poseidon for patronage of the city. At the western entrance are the spirited horsemen.

Elgin Marbles, East pediment of the Parthenon

In the world of the ancient Greeks there was a very close relationship between sculpture and architecture. Both temples and sculptures were created in order to honour the gods and the sculptures were not just an embellishment of the temple; together they combined to form an integrated and harmonious whole. The Parthenon is a good example and modern Greeks have long made the point that the so-called Elgin marbles, now a centerpiece of the British Museum, were an inseparable part of the Parthenon and cry out to be reunited with the building. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

The most famous of the marbles, the “Three Goddesses” , features three headless well-developed female images with clothing folded and draped gracefully and naturally on their bodies. Describing these figures in 1808, B.R. Haydon wrote, "I saw the arm was in repose and soft parts in relaxation. That combination of nature and idea which I had felt was so much wanting for high art was here displayed." I turned to the Theseus and saw that every form was altered by action or pose—when I saw that two sides of his back varied, one side stretched from the shoulder-blade being pulled forward, and the other side compressed from shoulder-blade being pushed close to the spine as he rested on his elbow...I saw in fact the most heroic style of art combined with all essential detail of actual life." The head of a horse that pulls the chariot of the moon goddess Selene has been described by the art critic and politician Boris Johnson as "the archetype in Western Art." Heralded for both its realism and emotional impact, the horse head features the bulging eyes, flared nostrils and gaping mouth of an exhausted animal.”

The battles with Amazons, giants and centaurs and scenes from the Trojan war that once graced the Parthenon are now in the British museum and called the Elgin Marbles. Perhaps the most striking and well known piece of classical Greek statuary, the Elgin Marbles are sections of a pediment and the 175-meter frieze that looped around the Parthenon. The Elgin Marble friezes contains images of battling horsemen and reclining deities, the most glorious of which are the “ Three Goddesses” . These three beautiful but headless female bodies have wonderful shape and form. Their clothing is folded and drops gracefully and naturally on the bodies.

The Elgin Marbles were brought to England from Greece and given to the British museum by Lord Elgin who paid of a Turkish sultan £35,000 for them. The first shipment of the friezes was lost at sea. Only the second shipment made it to the British Museum. Although the rightful owners of these treasures are perhaps the Greeks, removing them from Athens notorious pollution has kept them in better condition than they would have been in if they had stayed in Greece.

See Separate Article: ELGIN MARBLES: SCULPTURES, FRIEZES AND METOPES FROM THE PARTHENON europe.factsanddetails.com

Hellenistic Sculpture

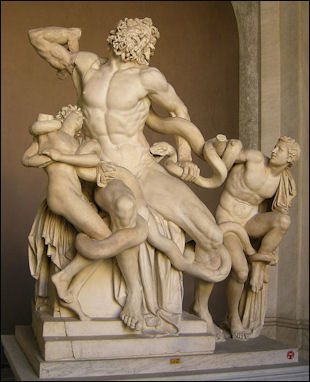

The Laocoon, a Hellenistic

period work Hellenistic Sculpture (323 B.C. to 31 B.C.) was much more varied and exquisitely-produced than sculpture made during the Classical period. Some of the most beautiful pieces of Greek statuary, including the Nike of Samonthrace, the Dying Gaul, Apollo Belvedere , and the Lacoön Group, date back to Hellenistic times. The Dying Gual has the hair and facial features of an ethnic Gaul.

The Lacoon, now at Vatican Museum, features a father and two sons struggling to entangle themselves from the grasps of giant serpents. The 2000-year-old statue depicts the punishment meted out to a priest who warned the Trojans to beware of Greeks bearing gifts.

Adam Masterman, wrote in Quora.com: During the Hellenistic period (323031 B.C.) sculpture fully embraced naturalism. Figures look like individuals instead of ideals, and a full range of emotions and actions are portrayed. Poses are the most diverse of any of the periods, representing a wide variety of actions and physical states. The anatomical detail is the most closely resembling real bodies (and thus the least idealized), and particular attention is paid to how bodies morph and change in different positions, showing a strong tradition of empirical observation. Finally, the work is more ornate than in any other period, reflecting a preference for complexity of design that can also be seen in the architecture of the time.

“Apollo Belvedere” , also at the Vatican Museum, glorifies the male body. Described by one critic as "a symbol of all that is young and free strong and gracious," it is most likely a Roman copy of a Greek bronze made by Leochares around 330 B.C. The original once stood in the Agora in Athens but is now lost. The copy lacks its left hand and most of its straight arm and scholars believe the right hand held a quiver and the left hand a bow. The elegant cloak is still in place. For several centuries it had a fig leaf over private parts.

Lost Greek Sculpture and Replicating Them

Venus de Milo restoration

with arms The reason so few ancient statues have survived is that many statues were burned in lime kilns to make mortar and plaster, and bronze statues were melted down for the metal by the Greeks and civilizations that followed them. Of the statues that remain hardly any have survived in one piece. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

These days observers of classical statues are fine viewing bodies with missing arms, broken torsos and other damaged good but that wasn’t always the case when the first Greek and Roman statues were unveiled to European audiences in the late 18th century. Then an effort was made to piece fragments together and replace any missing parts.

In the old days when a copy of a statue was made it required packing the statue in plaster to create a mold from which a copy could be caste. The direct application of plaster could damage the sculpture and damage pigment traces and other clues that archaeologists could use to determine the color of the statues and other things about it. Today, 3-D laser scanning can produce a copy without any contact to the original. The technology uses lasers to scan the image, replicating details down to small chisel marks. Reproductions can be made using rapid prototyping technologies in which 3-D objects are generated from computer data with machines that build up the object a layer at a time.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024