Home | Category: Art and Architecture

ANCIENT GREEK SCULPTURE

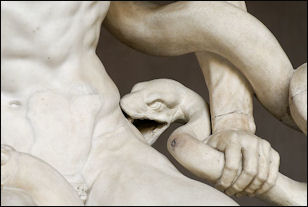

detail from the Laocoon Although marble is found everywhere on Greece, the Greeks did not begin making statues with it until after they became a seafaring people and witnessed the colossal monuments, statues and temples in Egypt.

Describing kouros at an exhibition titled "The Greek Miracle: Classical Sculptures from the Dawn of Democracy" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the 1990s, Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, “The first images to greet the visitor are the Metropolitan's own rose-tinged marble statue of a standing nude youth, or kouros, from the late seventh century B.C., and a few steps behind him is a sixth-century kouros from the National Archeological Museum in Athens... The contrast between the stiff, schematically rendered anatomy of the earlier figure and the supple form of the latter, his arms slightly bent as if anticipating an embrace, his face lifted in an unself-conscious smile, epitomizes in a stroke the development toward the "classical" style of the fifth century B.C. [Source: Holland Cotter, New York Times, March 12, 1993]

One of the most celebrated pieces in the show is the "Kritios Boy," the first surviving sculpture in Greek art to break away from the frontal rigidity of the archaic kouros to introduce a realistic depiction of the body's shifting weight and torsion. His white marble figure is a marvel of abstracted naturalism, though his lantern-jawed face has the thick, self-satisfied demeanor of a teen-age athlete just beginning to run to fat.”

There is a tradition of making copies of ancient Greek statues. The Romans, who greatly admired the Hellenic culture they’d conquered, carved many marble replicas of the Greek originals, which were usually cast in bronze.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; The Ancient City of Athens stoa.org/athens; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ;Ancient-Greek.org ancientgreece.com;Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Understanding Greek Sculpture: Ancient Meanings, Modern Readings”

by Nigel Spivey (1996) Amazon.com;

“Greek Sculpture. Function, Materials, and Techniques in the Archaic and Classical Periods” by Olga Palagia, editor (Cambridge University Press, 2006); Amazon.com;

“The Technique of Greek Sculpture in the Archaic and Classical Periods” by Sheila Adam (1966) Amazon.com;

“The Emergence of the Classical Style in Greek Sculpture” by Richard T. Neer (2013) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Greek Art: Sculpture and Vase Painting in the Archaic and Classical Periods” by Susan Woodford by Susan Woodford (1986, 2015) Amazon.com;

“Greek Sculpture” by John Boardman (1978) Amazon.com;

“Parthenon Sculptures” by Ian Jenkins Amazon.com;

“How to Read Greek Sculpture” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) by Sean Hemingway (2021) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Sculpture: An Image Archive for Artists and Designers” by Kale James Amazon.com;

“The Interpretation of Architectural Sculpture in Greece and Rome” by Diana Buitron-Oliver (1997) Amazon.com;

“A Manual of Ancient Sculpture, Egyptian – Assyrian – Greek – Roman: With One Hundred and Sixty Illustrations” by George Redford (2021) Amazon.com;

“Looking at Greek and Roman Sculpture in Stone: A Guide to Terms, Styles, and Techniques” by Janet Grossman (2003) Amazon.com;

“Textiles in Ancient Mediterranean Iconography” by Susanna Harris, Cecilie Brøns, Marta Zuchowska Amazon.com;

“Defining Beauty: the Body in Ancient Greek Art: Art and Thought in Ancient Greece”

by Ian Jenkins (2015) Amazon.com;

“Esthetic Basis of Greek Art” by Rhys Carpenter (1921) Amazon.com;

“Beauty: The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea” by David Konstan (2017)

Amazon.com;

“Hellenistic Sculpture” (World of Art) by R. R. R. Smith (1991) Amazon.com;

“Classical Art: From Greece to Rome (Oxford History of Art) by Mary Beard, John Henderson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

“Greek Art” (World of Art) by John Boardman (1964) Amazon.com;

“Archaic and Classical Greek Art” (Oxford History of Art) by Robin Osborne (1998) Amazon.com;

“Hellenistic Art: From Alexander the Great to Augustus” by Lucilla Burn (2005) Amazon.com;

Sculpture-Making in Ancient Greece

Sculptures and stone masons worked in the same medium and used the same tools. Both proceeded by similar stages, first roughing out the sculptural block or masonry column and then gradually cutting, dressing, and smoothing the stone once it was in place. To minimize the danger of accidental damage, the finishing was left until after the moving and hoisting had all been done. Finally tinted wax was worked into the pores of the marble to give the desired color to sculptured parts like hair, eyes, lips, costumes, moldings and metopes." [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

colored replica of

Peplos Kore as Artemis Sculptors worked with the same kind of mathematical precision that you'd expect from an architect. The architect Vitruvius once wrote: "Nature has so constructed the human body that the face...from the bottom of the chin to the lower edge of the nostrils is a third of its height; from the nostrils to the median termination of the eyebrows the length of the nose is another third."μ

The stone sculptures of the ancient Greeks would not appear familiar to us today. Shortly after the pieces were carved they were painted either completely or in part. That was consistent with Egyptian practice and it may have made sense in the bright sunlight of Greece. The statues also were outfitted with a range of accessories that would have made them resemble figures in a modern wax museum. Hair and eyelashes were fashioned out of metal. Eyes were inset and were made of glass, ivory or coloured stones. Female figures were often outfitted with earrings and necklaces. Athletes would have been shown wearing the victor’s wreath while warriors would be equipped with spears, shields and swords. Horses would have worn bridles and reins. If you look closely you can often see the holes for attachment of these accessories. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

The head and limbs of Greek stone statues were often made separately and attached to the statue torso using dowels and tenons of metal and stone. Occasionally, cement was used to fasten on smaller pieces. The huge statues of deities such as Athena and Zeus that were made of gold and ivory — chryselephantine (chrys = gold; elephantine =ivory) — deserve particular mention. They were huge works of art by any standards and remind us that the primary purpose of Greek sculptures, at least initially, was religious. They were the temple centerpieces and their production cost rivaled or exceeded that of the temple which housed them. A large wooden core made up the body of the statue to which sheets of beaten gold (for the clothing) and ivory (for the flesh) was added. The statue then was always the target in times of war or economic uncertainty. |

According to a review of the book “Greek Sculpture. Function, Materials, and Techniques in the Archaic and Classical Periods,” “Blocks abandoned in the quarries of Naxos, Paros, and Mount Hymettus show the process by which Archaic statues were given preliminary carving from rectangular blocks on site...Changes in quarrying methods in the second half of the sixth century are due to the development of new and better tools and result in the production of rounder figures with more spatial depth. Sturgeon examines the kouros and kore types separately and considers aspects such as their plinths and bases which, when available, can aid in recovering a more accurate presentation of the statues.” Sturgeon also “offers a wealth of little-known evidence for the technology of sculpture: piecing, attachments, joining methods (including anathyrosis), inset eyes, the use of metaL and paint.”

Marble, Bronze and Other Sculpture Materials

torso from a bronze equestrian statue

The Parian marble used to make statues like the “Venus de Medici” came from the island of Paros. The Pentelie marble used to make the Parthenon came from Mount Pentalieus. In areas that are short of stone sculptors made "acrolithic" statues, ones with heads and arms of marble attached to bodies of wood draped in cloth. Sometimes eyes, lips, nipples, hair, and clothing were painted in bright primary colors that were fixed in a wax covering. Other times tinted wax was worked into the pores of the marble to give the desired color to sculptured parts like hair, eyes, lips, costumes, moldings and metopes.. Some archaeologists say that many ancient Greek statues were so brightly colored they didn’t look all that different from kitschy images of saints and madonnas sold at souvenir stands today.

The Greeks produced numerous bronze statues but few of them have survived. Pliny mentioned that ancient Athens had 3,000 bronze statues. The majority of them were probably melted down by later generations of sculptors to make new sculptures. Most of those that have been discovered have been found in the sea. Greek bronzes were made hollow, cast with a clay core. Pieces were cast separately and soldered together. Sculptors patched up small defects made by air bubbles trapped in the original casting.

The Greeks used a variety of materials for their large sculptures: limestone, marble (which soon became the stone of choice- particularly Parian marble), wood, bronze, terra cotta, chryselephantine (a combination of gold and ivory) and, even, iron. The only material which has survived in any quantity is stone; the others were too precious or too fragile to survive the 25 centuries or so interval between the time of production and the present. The huge statues of deities such as Athena and Zeus that were made of gold and ivory- chryselephantine (chrys = gold; elephantine =ivory). [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

The quality of marble was closely linked to the place it was quarried In her study of kouroi According to a review of the book “Greek Sculpture. Function, Materials, and Techniques in the Archaic and Classical Periods,” Mary Sturgeon “shows that the marble from Naxos was exploited first. from the second half of the seventh century onwards. The beginning of the sixth century sees the export in Parian statues, and by the middle of the century, this marble dominates the Greek market, with Hymettan stone initially used only for architectural sculpture. Pentelic marble has an even more limited application, but occasional use occurs for korai throughout this century; its heyday falls after the Persian destruction in 480 B.C..”

See Separate Article: BRONZE ART IN ANCIENT GREEK: STATUES, VESSELS, THE LOST-WAX TECHNIQUE europe.factsanddetails.com

Contexts for the Display of Ancient Greek Statues

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In the classical world, large-scale, freestanding statues were among the most highly valued and thoughtfully positioned works of art. Sculpted in the round, and commonly made of bronze or stone, statues embodied human, divine, and mythological beings, as well as animals. Our understanding of where and how they were displayed relies on references in ancient texts and inscriptions, and images on coins, reliefs, vases, and wall paintings, as well as on the archaeological remains of monuments and sites. Even in the most carefully excavated and well-preserved locations, bases usually survive without their corresponding statues; dispersed fragments of heads and bodies provide little indication of the visual spectacle of which they once formed a part. Numerous statues exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum, for example, have known histories of display in old European collections, but their ancient contexts can only be conjectured. [Source: Marden Nichols, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

the Elgin Marbles were originally part of the Parthenon

“Among the earliest Greek statues were images of divinities housed in temples, settings well suited to communicate their religious potency. The Greeks situated these standing or seated figures, which often wore real clothing and held objects associated with their unique powers, on axis with temple entrances for maximum visual impact. By the mid-seventh century B.C., rigidly upright statues in stone, referred to as kouroi (youths) and korai (maidens), marked gravesites and were dedicated to the gods as votive offerings in sanctuaries. Greek sanctuaries were sacred, bounded areas, typically encompassing an altar and one or more temples. Evidence for a range of display contexts for statues is more extensive for the Classical period. Public spaces ornamented with statues included open places of assembly like the Athenian agora, temples, altars, gateways, and cemeteries. Statues of athletic contest winners were often erected at large sanctuaries such as Olympia and Delphi, or sometimes in the victors' hometowns. \^/

“Throughout the Archaic and Classical periods, however, the focus of statue production and display remained the representation and veneration of the gods. From the sixth to fifth centuries B.C., hundreds of statues were erected in honor of Athena on the Athenian Akropolis. Whether in a shrine or temple, or in a public space less overtly religious, such as the Athenian agora, statues of deities were reminders of the influence and special protection of the gods, which permeated all aspects of Greek life. By the end of the fifth century B.C., a few wealthy patrons began to exhibit panel paintings, murals, wall hangings, and mosaics in their houses. Ancient authors are vocal in their condemnation of the private ownership and display of such art objects as inappropriate luxuries (for example, Plato's Republic, 372 D–373 A), yet pass no judgment on the statuettes these patrons also exhibited at home. The difference in attitude suggests that even in private space, statues retained religious significance. \^/ “The ideas and conventions governing the exhibition of statues were as reliant on political affairs as they were on religion. Thus the changes in state formation set in motion by Alexander the Great's conquest of the eastern Mediterranean brought about new and important developments in statue display. During the Hellenistic period, portrait statuary provided a means of communicating across great distances both the concept of government by a single ruler and the particular identities of Hellenistic dynasts. These portraits, which blend together traditional, idealized features with particularized details that promote individual recognition, were a prominent feature of sanctuaries dedicated to ruler cults. Elaborate victory monuments showcased statues of both triumphant and defeated warriors. Well-preserved examples of such monuments have been discovered at Pergamon, in the northwestern region of modern-day Turkey. For the first time, nonidealized human forms, including the elderly and infirm, became popular subjects for large-scale sculptures. Statues of this kind were offered as votives in temples and sanctuaries. The extensive collections housed within the palaces of Hellenistic dynasts became influential models for generals and politicians in far-away Rome, who coveted such displays of power, prestige, and cultural sophistication. \^/

Sculpture and Color

When we think of Greek and Roman statues we think of white marble. When the Greek statuary was rediscovered in the Renaissance it was assumed that it was white and that become the norm that Renaissance artists such as Michelangelo tried to emulate. However, the Greeks painted their statues and decorated them with wire eyelashes, tinted nipples and inserted glass eyes.

When we think of Greek and Roman statues we think of white marble. When the Greek statuary was rediscovered in the Renaissance it was assumed that it was white and that become the norm that Renaissance artists such as Michelangelo tried to emulate. However, the Greeks painted their statues and decorated them with wire eyelashes, tinted nipples and inserted glass eyes.

The 18th-century scholar Johann Winckelmann used the phrase “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur” to describe the qualities that were pleasing about Greek and Roman statuary. He wrote “the whiter the body is, the more beautiful it is as well. Color contributes to beauty, because it is not [color] but structure that constitutes its essence.”

But this is not the reality of the statues in their original forms. When Greek statues were created they were often painted in what was would seem today to be bright, garish colors. This first came to light in a graphic way when sculptures from a mythical battle scene were pulled out of excavations of the Temple of Aphaia on the Greek island of Aegina in 1811. Some of the sculptures has red paint to mimic oozing blood as well as holes used for various props and accouterments attached to the statue.

The German archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkman has made it his mission to uncover what original Greek sculptures looked like — using chemical analysis, high-intensity lamps, ultraviolet light, cameras — and then recreating the original materials and finally creating copies of the statues with plaster and marble, hand painted in bright colors using pigments made of the same materials used by the ancient Greeks such as green made from malachite, blue from azurite, yellow and ocher from arsenic compounds, red from cinnabar, black from burned bone and vine. Some of Brinkmann’s work can be seen at the Glyptothek Museum in Munich and have been displayed at a number of museums around the world including Harvard’s Sackler Museum in 2007.

Painted Greek warrior head Brinkmann’s most useful tool is a hand-held spotlight which he shines on the sculptures late in the day when the light is low it achieve “extreme raking light” (a technical term for light that falls on a surface from the side at a very low angle) to detect faint incisions that would otherwise be near impossible to detect with the naked eye. These markings help him determine images and patterns. Pigment colors are mostly determined from chemical analysis. Ultraviolet light locates color shadows — where some pigments were applied more slowly that others — providing more insights into colors used and possible mixing of colors, shading and shadowing.

A reconstruction of an archer — thought to be Paris, the man who started the Trojan war — found at the Temple of Aphaia recreated by Brinkman features: 1) flowing hair made of molded lead, painted brown, which was fitted into holes in the statue’s head; 2) bronze arrows and a bronze and marble bow; 3) bright colors determined by traces of pigments and variation in the stone’s weathering (durable vermilion protects stones better than fragile yellow ochers, for example; and 4) images and intricate patterns worked out by the presence of incised lines and patterns that show up under ultraviolet light.

Nudes in Greco-Roman Art

Jean Sorabella wrote for the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The nude first became significant in the art of ancient Greece, where athletic competitions at religious festivals celebrated the human body, particularly the male, in an unparalleled way. The athletes in these contests competed in the nude, and the Greeks considered them embodiments of all that was best in humanity. It was thus perfectly natural for the Greeks to associate the male nude form with triumph, glory, and even moral excellence, values which seem immanent in the magnificent nudes of Greek sculpture (25.78.56). Images of naked athletes stood as offerings in sanctuaries, while athletic-looking nudes portrayed the gods and heroes of Greek religion. The celebration of the body among the Greeks contrasts remarkably with the attitudes prevalent in other parts of the ancient world, where undress was typically associated with disgrace and defeat. The best-known example of this more common view is the biblical story of Adam and Eve, where the first man and woman discover that they are naked and consequently suffer shame and punishment. [Source: Jean Sorabella, Independent Scholar, Metropolitan Museum of Art, January 2008, metmuseum.org \^/]

Venus de Milo

“The ancestry of the female nude is distinct from the male. Where the latter originates in the perfect human athlete, the former embodies the divinity of procreation. Naked female figures are shown in very early prehistoric art, and in historical times, similar images represent such fertility deities as the Near Eastern Ishtar. The Greek goddess Aphrodite belongs to this family, and she too was imagined as life-giving, proud, and seductive. For many centuries, the Greeks preferred to see her clothed, unlike her Near Eastern counterparts, but in the mid-fourth century B.C., the sculptor Praxiteles made a naked Aphrodite, called the Knidian, which established a new tradition for the female nude. Lacking the bulbous and exaggerated forms of Near Eastern fertility figures, the Knidian Aphrodite, like Greek male athletic statues, had idealized proportions based on mathematical ratios. In addition, her pose, with head turned to the side and one hand covering the body, seemed to present the goddess surprised in her bath and thus fleshed the nude with narrative and erotic possibilities. The position of the goddess' hands may be meant to show modesty or desire to shield the viewer from too full a view of her godhead. Although the Knidian statue is not preserved, its impact survives in the numerous replicas and variants of it commissioned in the Hellenistic (12.173) and Roman (52.11.5) eras. Such images of Venus (the Latin name of Aphrodite) adorned houses, bath buildings, and tombs as well as temples and outdoor sanctuaries. \^/

“Since the nudes of ancient Greece and Rome became normative in later Western art, it is worth pausing to consider what they are and are not. They express profound admiration for the body as the shape of humanity, yet they do not celebrate human variety; they may have sex appeal, yet they are never totally prurient in intent. The nudes of Greco-Roman art are conceptually perfected ideal persons, each one a vision of health, youth, geometric clarity, and organic equilibrium. Kenneth Clark considered idealization the hallmark of true nudes, as opposed to more descriptive and less artful figures that he considered merely naked. His emphasis on idealization points up an essential issue: seductive and appealing as nudes in art may be, they are meant to stir the mind as well as the passions." \^/

The few female sculptures produced were usually clothed and the clothing was painted. There were very female nudes in Greek art until the forth century B.C. when Praxiteles began creating cult images of a nude Aphrodite. One of the first Greek statues to reveal the body of woman was Dying Niobid (450-440 B.C.). According to legend Niobid boasted about her fourteen children and humiliated the mother of Apollo and Artemis. To get even the two gods killed all of her children and then shot her in the back with an arrow. In an frantic attempt to reach back and remove the arrow her peplos fell off. The nude statue of her is the earliest large female nude in Greek art. The first images of Aphrodite (Venus) stepping out of a scallop shell were statues found in Anatolian Turkey. [Source: "History of Art" by H.W. Janson, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.]

Sculpture, Sports and Nudity in Ancient Greece

While male gods and athletes were sculpted in the nude, goddesses and women were usually chiseled fully clothed. The exception was Aphrodite who was often depicted with her breasts blossoming from the top of her chilton.

The male subjects of Greek statues were often in the nude because the athletes they depicted competed in the nude. Instead of using models in a studio early Greek sculptor and painters worked from athletes exercising in a gymnasium. When the painter Zeuxis asked for models to use in his painting of Helen of Troy he was taken to a boy's gymnasium and told to imagine the beauty of their sisters. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

discus thrower from the 2nd century BC

Many scholars link the development of Greek statuary art with the rise in the popularity of Greek athletics. Some towns had thousands of athletic statues and citizens often sought them out as cures for illnesses for the same reason citizens in modern Chinese eat bear gall bladders: they believed that the strength emanating out the statues would be passed on to them.

Olympians competed in the nude. In some competitions and during the opening and closing ceremonies they often covered themselves in perfumed oils. Even jockeys wore nothing. Wrestlers in the nude often had their foreskin tied over the tip of the penis for protection. The only exception was the charioteers who wore long white robes. Nudity was seen as a way of making all competitors equal by stripping social ranks they could otherwise express with their clothes. See Olympics and Nudity

The victor in the various athletic festivals or his supporters often paid for a statue of the athlete, erected either at the festival site or in his hometown. In the case of the Spartan woman Kyniska who won the four-horse chariot race at the Olympics in 396 B.C. she had a bronze commemorative statue erected at Olympia. (Unfortunately only the fractured base and a part of the inscription text remains. As was often the case with large bronze sculptures it was likely melted down for the valuable metal.) The famous bronze charioteer from Delphi is one votive offering that did survive. In addition, statues were often commissioned in remembrance of an historical event. (e.g. the equally-famous Tyrannicides statues which commemorated the assassination of the tyrant Hipparchos) The need for private grave markers and memorials also contributed to the on-going demand for statues. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

See Separate Article: ANCIENT OLYMPIC ATHLETES: TRAINING, NUDITY, WINNERS AND CHEATERS europe.factsanddetails.com

Idealized Naturalism in Ancient Greek Sculpture

Harold Koda of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The Roman poet Ovid recounted an ancient myth in which Pygmalion, a sculptor disenchanted by mortal women, creates an image of feminine perfection. When he becomes enthralled with his own sculpted ideal, Venus—the Greek Aphrodite—responds to his prayers and brings the statue to life as Galatea.” [Source: Harold Koda, The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

The evolution of Greek sculpture is a journey from the realm of the rigid and stylized towards the ideal of naturalism. Early figures resemble a mathematical formula executed in a hard and unyielding medium. It is as if the sculptures have emerged rigid from a frozen block of material. Late figures are far more relaxed and natural to the extent that one could easily imagine the statue taking a breath. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

Wet Drapery in Ancient Greek Sculpture

Many Ancient Greek monuments highlight drapery (clothing draped on the the body). It must have been the fashion of the sixth to the middle of the fifth centuries B.C. to lay the folds of men’s dress, as well as of women’s, in symmetrically parallel lines. In pictures the lower edges of dresses and cloaks show various regularly cut-out points, while on the inner side there are many small zigzag folds arranged with laborious symmetry. This may be partly due to the artistic style, which at that period inclined to over-elaboration; yet it is impossible to doubt that we find here not only an expression of archaic art, but also the representation of a dress laboriously and artificially folded, stiffened, and ironed, in which the folds were produced by external aids, such as ironing, starching, pressing, even stitching of the stuff laid in folds, or sewing such folds on to the material. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

One of the most outstanding features of quality ancient Greek sculptures such as the Elgin Marbles is the way loose, elaborately folded and wrinkled clothing is draped on the human body. Koda wrote: Wet-drapery is a “a term used by art historians to describe cloth that appears to cling to the body in animated folds while it reveals the contours of the form beneath (Victory of Samothrace, Musée du Louvre, Paris). This sculptural characteristic” is “evidenced in figures from the classical and Hellenistic periods. In Greek art, fabrics are rendered with the texture of both regular folds and irregular pleating.” [Source: Harold Koda, The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

The most famous of the marbles, the “Three Goddesses” , features three headless well-developed female images with clothing folded and draped gracefully and naturally on their bodies. Describing these figures in 1808, B.R. Haydon wrote, "I saw the arm was in repose and soft parts in relaxation. That combination of nature and idea which I had felt was so much wanting for high art was here displayed...I turned to the Theseus and saw that every form was altered by action or pose—when I saw that two sides of his back varied, one side stretched from the shoulder-blade being pulled forward, and the other side compressed from shoulder-blade being pushed close to the spine as he rested on his elbow...I saw in fact the most heroic style of art combined with all essential detail of actual life."

some intense drapery on the Elgin Marble

We cannot determine when this custom began in Greece. In works of art we find it comparatively late in the sixth century B.C.; yet it is by no means impossible that this fashion existed at a far more ancient period, since the custom of laying material in artificial folds by means of stiffening or ironing was already known in Egypt in 4000 B.C.; and it therefore seems extremely probable that the Phoenicians adopted the practice at a very early period, and introduced it into Greece. It is a very natural assumption that this mode of draping would in the first instance be adopted for linen material, and that it would therefore be introduced among the Greeks with the linen chiton, which took the place of the woollen one formerly worn.

On the other hand, however, it is probable that, as woollen clothing was afterwards worn as well as linen, they attempted to ornament this in similar fashion by artificial folds; the works of art, however, show that these folds were far less in quantity and less sharply defined in woollen clothing than in linen, which is naturally much better adapted for the purpose. Apart from the folds, the clothes now became wider and more comfortable, and were less closely girt round the hips. The chiton is still a garment made by sewing, and the long differs from the short only in length, not in shape.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK CLOTHES europe.factsanddetails.com

Retrospective Styles in Ancient Greek Sculpture

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “From at least the fifth century B.C. on, Greek artists deliberately represented certain works of art in the style of previous generations in order to differentiate them from other works in contemporary style. Features of retrospective styles may occur in the pose of a figure, its garment type and drapery pattern, its facial features, or its hairstyle. In Greek and Roman sculpture, two retrospective styles predominate: archaistic and classicizing. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Metropolitan Museum of Art, July 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Archaistic, the most common retrospective style in Greek and Roman sculpture, refers to works of art that date after 480 B.C., but share stylistic affinities with works of the Greek Archaic period (ca. 700-480 B.C.). Archaistic figures stand with legs unbent and occasionally with one leg forward. The shoulders and hips are level and the head faces directly forward. In general, the most often imitated costumes are the late Archaic chiton combined with a diagonal himation of the type worn by many korai from the Athenian Akropolis, and the peplos with a long overfold belted at or above the waist. Archaistic drapery folds typically hang straight, and there is often a broad central pleat. Facial features and hairstyles of archaistic figures usually imitate those of Archaic sculpture-heavy-lidded eyes, high cheekbones, and sometimes a hint of the Archaic smile. The hair is styled with long spiral tresses, and snail curls over the forehead are favored for male figures and herms. \^/

“From the first century B.C. to the second century A.D., the so-called neo-Attic relief sculptors adapted works of previous artistic periods—the late Archaic, the mid-fifth century B.C., and the second half of the fourth century B.C.—and regrouped them in compositions, often for decorative purposes. To what extent neo-Attic artists adhered to their prototypes is a question than can be answered only by carefully considering each work individually. \^/

Reasons for Retrospective Styles

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The function of retrospective style in Greco-Roman sculpture is one of continuing debate. Perhaps Greek and Roman artists intentionally drew upon stylistic features of earlier artistic periods in order to distinguish specific representations as divine or otherworldly. For example, Spes, the personification of hope, is commonly shown as an archaistic maiden. The Hope Dionysos, in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum, features such an archaistic figure. Her pose and costume distinctly differ from the figure of Dionysos shown standing at ease and wearing more naturalistically rendered attire. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Metropolitan Museum of Art, July 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Retrospective style also distinguishes some statues as boundary markers, or as steadfast guardians. Herms—square pillars topped with a bust of the Greek god Hermes—were used as boundary markers and protective images at doorways and along roads in ancient Greece and Rome. Most herms are represented in a retrospective style, which seems appropriate for an image that needed to remain steadfast in order to function properly. Hekate, goddess of the moon and nocturnal sorcery, was a popular deity and guardian in Greek and Roman times. Triple-bodied representations of the goddess, known as hekateia, frequently stood in front of private homes and at crossroads. Generally, hekateia are depicted in archaistic costume comprising a peplos with a long, belted overfold, symmetrical pleats, and a triangular pattern of folds at the neckline. The archaistic style endows the hekateia with qualities of permanence and stability. \^/

“Generally, an older style also lends an air of venerability and authenticity to a religious image and its cult. And iconography played an important role in the selection of sculptural types. Hellenistic religious preferences may have dictated that an archaistic style be used for images of the Greek god Dionysos, or a classicizing style for statues of the Greek goddess Artemis. \^/

“As the political dominance of Rome spread throughout the Mediterranean in the second and first centuries B.C., the Romans increasingly became the chief patrons of Greek art, and the achievements of Classical Greece came to be looked upon with awe and reverence. A neoclassical tradition, centered particularly in Athens, developed late in the second century B.C. It emulated Classical art and catered especially to Roman clientele. \^/

“Retrospective styles continued to flourish under the emperor Augustus, who wished his empire to emulate and surpass the achievements of the golden age of Classical Greece. Wealthy Romans filled their villa courtyards and gardens with fountains, sculpture, and monumental vases, many of which were decorated with motifs drawn from the Greek art produced some 500 years earlier.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024