Home | Category: Art and Architecture

EARLY CYCLADIC ART AND CULTURE (3200-2300 B.C.)

Cycladic vase from the 4th millennium BC

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The Cyclades, a group of islands in the southwestern Aegean, comprises some thirty small islands and numerous islets. The ancient Greeks called them kyklades, imagining them as a circle (kyklos) around the sacred island of Delos, the site of the holiest sanctuary to Apollo. Many of the Cycladic Islands are particularly rich in mineral resources—iron ores, copper, lead ores, gold, silver, emery, obsidian, and marble, the marble of Paros and Naxos among the finest in the world. Archaeological evidence points to sporadic Neolithic settlements on Antiparos, Melos, Mykonos, Naxos, and other Cycladic Islands at least as early as the sixth millennium B.C. These earliest settlers probably cultivated barley and wheat, and most likely fished the Aegean for tunny and other fish. They were also accomplished sculptors in stone, as attested by significant finds of marble figurines on Saliagos (near Paros and Antiparos). [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“In the third millennium B.C., a distinctive civilization, commonly called the Early Cycladic culture (ca. 3200–2300 B.C.), emerged with important settlement sites on Keros and at Halandriani on Syros. At this time in the Early Bronze Age, metallurgy developed at a fast pace in the Mediterranean. It was especially fortuitous for the Early Cycladic culture that their islands were rich in iron ores and copper, and that they offered a favorable route across the Aegean. Inhabitants turned to fishing, shipbuilding, and exporting of their mineral resources, as trade flourished between the Cyclades, Minoan Crete, Helladic Greece, and the coast of Asia Minor. \^/

“Early Cycladic culture can be divided into two main phases, the Grotta-Pelos (Early Cycladic I) culture (ca. 3200?–2700 B.C.), and the Keros-Syros (Early Cycladic II) culture (ca. 2700–2400/2300 B.C.). These names correspond to significant burial sites. Unfortunately, few settlements from the Early Cycladic period have been found, and much of the evidence for the culture comes from assemblages of objects, mostly marble vessels and figurines, that the islanders buried with their dead. Varying qualities and quantities of grave goods point to disparities in wealth, suggesting that some form of social ranking was emerging in the Cyclades at this time. \^/

“The majority of Cycladic marble vessels and sculptures were produced during the Grotta-Pelos and Keros-Syros periods. Early Cycladic sculpture comprises predominantly female figures that range from simple modification of the stone to developed representations of the human form, some with natural proportions and some more idealized. Many of these figures, especially those of the Spedos type, display a remarkable consistency in form and proportion that suggests they were planned with a compass. Scientific analysis has shown that the surface of the marble was painted with mineral-based pigments—azurite for blue and iron ores, or cinnabar for red. The vessels from this period—bowls, vases, kandelas (collared vases), and bottles—display bold, simple forms that reinforce the Early Cycladic predilection for a harmony of parts and conscious preservation of proportion. \^/

Categories with related articles in this website: Ancient Greek History (48 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Art and Culture (21 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Life, Government and Infrastructure (29 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden–Sydney College, Virginia hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ; Ancient-Greek.org ancientgreece.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; The Ancient City of Athens stoa.org/athens; The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT rtfm.mit.edu; 11th Brittanica: History of Ancient Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ;Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu

Minoan Art

Minoan frescoes The Minoans are widely admired today for their art. They produced lovely frescos of dancers and bulls and made wild abstracts patterns on vases. Some Minoan engravings of women give them strange robot-like heads. They also produced extraordinary rhytons (liquid-containing vessels) made to look like bulls heads.

Animals and sea creatures were commonly depicted in Minoan art. Octopuses strangled vases, dolphins leaped from murals, and mountain goats dashed across vessels. One mural fragment shows a cat stalking a pheasant from behind a bush. One scholar claimed that the Minoans had a "passion for rhythmic, undulating movement."

The Minoans created pottery on hand-tuned wheels (2500 B.C.) and made earthen storage jars as tall as a man and thin shelled libation vessels decorated with starfish and sea shell motifs. Potters in Crete still make pottery using the same techniques as the Minoans.

According to the Canadian Museum of History: “The Minoans were gifted artists and that the subject matter of their artworks seems to have been heavily influenced by aesthetic considerations. Some have suggested that they may have loved art for its own sake, which would be an enormous change in the way art was traditionally created and used in other societies at that time. But more research on that possibility is needed. [Source: Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca ]

Colette Hemingway and Seán Hemingway of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: During the first half of the second millennium B.C. “great strides were made in metalworking and pottery—exquisite filigree, granulated jewelry, and carved seal stones reveal an extraordinary sensitivity to materials and dynamic forms. These characteristics are equally apparent in a variety of media, including clay, gold, stone, ivory, and bronze. [Source: Colette and Seán Hemingway, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002 metmuseum.org \^/]

See Minoan Religion

Art at the Heraklion Museum

Minoan dolphins

Heraklion Museum is one of the best museums in Greece and contains almost all of the world's Minoan artifacts. Among the museum’s treasures are ceramic polychrome vases found in the Kamares caves; marble vases encrusted with precious and semi-precious stones; sealstones carved out of semiprecious stones; gold ornaments; frescoes and sarcophagi. Particularly interesting are ceremonial axes and knives used in sacrifices; and libation jars used to collect the blood from the animals necks. Goats and bulls were the animals most commonly offered. Paintings on sarcophagi suggest that spotted bulls were the animals of choice. These same paintings show that the bull was tied down to a table and serenaded by a flutist while it bled.

Vases depict men partying, shacking Egyptian rattles and singing so hard the ribs are pressed against their skin from lack of breath. A popular image was the bare breasted snake goddess with snakes crawling up her arms, around her head and tied into a knot about her waist. One of the unusual things about the worship of snakes by the Minoans is that Crete has virtually no snakes. Some miniature plaques show what Minoan houses looked like. There are also sculptures of dancers and bare-breasted maidens with snakes in their hands, vessels with starfish; massive knuckle covering gold rings with women with robot heads and frescoes of bull leapers.

The Archaeological Museum of Herakleion contains more than 15,000 artefacts, spanning a period of 5,000 years, from the Neolithic era to Greco-Roman period, and collected from excavations carried out in all parts of Crete. The pieces include pottery in a variety of utilitarian yet imaginative shapes; stone carving of exceptional artistry; seal engraving; miniature sculpture; gold work; metalwork; household utensils; tools; weapons and sacred axes. The highlight is the frescoes, with their exquisitely-rendered figures and thoughtful, colorful compositions. [Source: Interkriti]

Minoan golden bee

The pieces include: 1) a Libation vase (rhyton) of serpentine, in the shape of a bull's head with inlays of shell, rock crystal and jasper in the muzzle and eyes from Little Palace in Knossos and dated to 1600 - 1500 B.C.; 2) a flask decorated with a large octopus and supplementary motifs: sea urchins, seaweed and rocks from Palaikatsro (East Sitia) and dated to around 1400 B.C.; 3) a slender libation jug with spiky projections, decorated with painted papyrus flowers and nautilus from a grave at Katsambas (Iraklion) and dated to 1450-1400 B.C.; and 4) the famous "Harvesters' Vase", a steatite oval rhyton decorated with a relief procession of men returning from their work in the fields, from Agia Triada and dated to 1500 - 1450 B.C..

The Minoans developed tools capable of cutting even the hardest stones. Among the items that had to have been produced with such tools are: a large lenticular sealstone, made of agate, depicting a goddess between griffins from Knossos and dated to 1450 - 1400 B.C.) In the New Palace period (1600-1450 B.C.) bronze work advanced and miniature bronze sculpture became relatively common. Animal figures, such as a seated wild goat, from Agia Triada, were typically smaller than the human ones. Unfortunately the most surviving examples of Minoan fresco paintings are fragmentary. The "Blue Bird", a fresco with a blue bird sitting on a rock among plants and flowers, was part of a larger composition from the "House of Frescoes" at Knossos, dated to the Neopalatial period (1550 - 1500 B.C.).

Examples of finely crafted metalwork include 1) a gold lion-shaped pendant from Agia Triada from the Post Palatial period (1450-1100 B.C.); 2) a silver pot (kylix) with gold plated handle and rim from a grave in Knossos area from the Final Palatial period (1450 - 1350 B.C.); 3) a bronze sword with gold-sheathed hilt and gold covered rivets, decorated with relief spirals from a cemetery in the Knossos area from the Final Palatial period (1450 - 1400 B.C.); and 4) a gold votive double axe with incised decorations from Arkalochori cave from the Early Neopalatial period (1700 - 1600 B.C.).

Mycenaean Art (1600-1100 B.C.)

Mycenaean ceramics, painted with distinctive shiny red and black images, was crafted into storage jars and ceremonial vessels.

The Mycenaeans built large palaces with specialized rooms for food storage, repairing chariots, making ceramics, keeping archives and writing records on stone tablets. Many of the walls were plastered and some were decorated with frescoes.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “During the Mycenaean period, the Greek mainland enjoyed an era of prosperity centered in such strongholds as Mycenae, Tiryns, Thebes, and Athens. Local workshops produced utilitarian objects of pottery and bronze, as well as luxury items, such as carved gems, jewelry, vases in precious metals, and glass ornaments. Contact with Minoan Crete played a decisive role in the shaping and development of Mycenaean culture, especially in the arts. [Source: Colette Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

Geometric Art in Ancient Greece (900 to 700 B.C.)

Geometric style vase

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The roots of Classical Greece lie in the Geometric period of about ca. 900 to 700 B.C., a time of dramatic transformation that led to the establishment of primary Greek institutions. The Greek city-state (polis) was formed, the Greek alphabet was developed, and new opportunities for trade and colonization were realized in cities founded along the coast of Asia Minor, in southern Italy, and in Sicily. With the development of the Greek city-states came the construction of large temples and sanctuaries dedicated to patron deities, which signaled the rise of state religion. Each polis identified with its own legendary hero. By the end of the eighth century B.C., the Greeks had founded a number of major Panhellenic sanctuaries dedicated to the Olympian gods. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art. "Geometric Art in Ancient Greece", Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Geometric Greece experienced a cultural revival of its historical past through epic poetry and the visual arts. The eighth century B.C. was the time of Homer, whose epic poems describe the Greek campaign against Troy (the Iliad) and the subsequent adventures of Odysseus on his return to Ithaca (the Odyssey). A newly emerging aristocracy distinguished itself with material wealth and through references to the Homeric past. Their graves were furnished with metal objects, innately precious by the scarcity of copper, tin, and gold deposits in Greece. \^/

“Evidence for the Geometric culture has come down to us in the form of epic poetry, artistic representation, and the archaeological record. From Hesiod (Erga, 639–640), we assume that most eighth century B.C. Greeks lived off the land. The epic poet describes the difficult life of the Geometric farmer. There are, however, few archaeological remains that describe everyday life during this period. Monumental kraters, originally used as grave markers, depict funerary rituals and heroic warriors. The presence of fine metalwork attests to prosperity and trade. In the earlier Geometric period, these objects, weapons, fibulae, and jewelry are found in graves—most likely relating to the status of the deceased. By the late eighth century B.C., however, the majority of metal objects are small bronze figurines—votive offerings associated with sanctuaries. \^/

“Votive offerings of bronze and terracotta, and painted scenes on monumental vessels attest to a renewed interest in figural imagery that focuses on funerary rituals and the heroic world of aristocratic warriors and their equipment. The armed warrior, the chariot, and the horse are the most familiar symbols of the Geometric period. Iconographically, Geometric images are difficult to interpret due to the lack of inscriptions and the scarcity of identifying attributes. There can be little doubt, however, that many of the principal characters and stories of Greek mythology already existed, and that they simply had not yet received explicit visual form. \^/ “Surviving material shows a mastery of the major media—turning, decorating, and firing terracotta vases; casting and coldworking bronze; engraving gems; and working gold. The only significant medium that had not yet evolved was that of monumental stone sculpture—large-scale cult images most likely were constructed of a perishable material such as wood. Instead, powerful bronze figurines and monumental clay vases manifest the clarity and order that are, perhaps, the most salient characteristics of Greek art. \^/

Greek Art in the Archaic Period (700 to 490 B.C.)

Archaic style vase

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “A striking change appears in Greek art of the seventh century B.C., the beginning of the Archaic period. The abstract geometric patterning that was dominant between about 1050 and 700 B.C. is supplanted in the seventh century by a more naturalistic style reflecting significant influence from the Near East and Egypt. Trading stations in the Levant and the Nile Delta, continuing Greek colonization in the east and west, as well as contact with eastern craftsmen, notably on Crete and Cyprus, inspired Greek artists to work in techniques as diverse as gem cutting, ivory carving, jewelry making, and metalworking. Eastern pictorial motifs were introduced—palmette and lotus compositions, animal hunts, and such composite beasts as griffins (part bird, part lion), sphinxes (part woman, part winged lion), and sirens (part woman, part bird). Greek artists rapidly assimilated foreign styles and motifs into new portrayals of their own myths and customs, thereby forging the foundations of Archaic and Classical Greek art art. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art. "Greek Art in the Archaic Period", Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003. metmuseum.org \^/]

“The Greek world of the seventh and sixth centuries B.C. consisted of numerous autonomous city-states, or poleis, separated one from the other by mountains and the sea. Greek settlements stretched all the way from the coast of Asia Minor and the Aegean islands, to mainland Greece, Sicily, North Africa, and even Spain. As they grew in wealth and power, the poleis on the coast of Asia Minor and neighboring islands competed with one another in the construction of sanctuaries with huge stone temples. Lyric poetry, the primary literary medium of the day, attained new heights in the work of such notable poets as Archilochos of Paros and Sappho of Lesbos. Contact with prosperous centers like Sardis in Lydia, which was ruled in the sixth century B.C. by the legendary king Croesus, influenced eastern Greek art. Sculptors in the Aegean islands, notably on Naxos and Samos, carved large-scale statues in marble. Goldsmiths on Rhodes specialized in fine jewelry, and bronzeworkers on Crete fashioned armor and plaques decorated with superb reliefs. \^/

“The prominent artistic centers of mainland Greece—notably Sparta, Corinth, and Athens—also exhibited significant regional variation. Sparta and its neighbors in Laconia produced remarkable ivory carvings and distinctive bronzes. Corinthian artisans invented a style of silhouetted forms that focused on tapestry-like patterns of small animals and plant motifs. By contrast, the vase painters of Athens were more inclined to illustrate mythological scenes. Despite variance in dialect—even the way the alphabet was written varied from region to region at this time—the Greek language was a major unifying factor in Greece. Furthermore, Greek-speaking people came together for festivals and the games that were held at the major Panhellenic sanctuaries on mainland Greece, such as Olympia and Delphi. Dedications at these sanctuaries included many works from the eastern and western regions of Greece. \^/

“Throughout the sixth century B.C., Greek artists made increasingly naturalistic representations of the human figure. During this period, two types of freestanding, large-scale sculptures predominated: the male kouros, or standing nude youth, and the female kore, or standing draped maiden. Among the earliest examples of the type, the kouros in the Metropolitan Museum reveals Egyptian influence in both its pose and proportions. Erected in sanctuaries and in cemeteries outside the city walls, these large stone statues served as dedications to the gods or as grave markers. Athenian aristocrats frequently erected expensive funerary monuments in the city and its environs, especially for members of their family who had died young. Such monuments also took the form of stelai, often decorated in relief. \^/

Medusa from the Archaic period

“Sanctuaries were a focus of artistic achievement at this time and served as major repositories of works of art. The two main orders of Greek architecture—the Doric order of mainland Greece and the western colonies, and the Ionic order of the Greek cities on the coast of Asia Minor and the Ionian islands—were well established by the beginning of the sixth century B.C. Temple architecture continued to be refined throughout the century by a process of vibrant experimentation, often through building projects initiated by rulers such as Peisistratos of Athens and Polykrates of Samos. These buildings were often embellished with sculptural figures of stone or terracotta, paintings (now mostly lost), and elaborate moldings. True narrative scenes in relief sculpture appeared in the latter part of the sixth century B.C., as artists became increasingly interested in showing figures, especially the human figure, in motion. About 566 B.C., Athens established the Panathenaic games. Statues of victorious athletes were erected as dedications in Greek sanctuaries, and trophy amphorai were decorated with the event in which the athlete had triumphed. \^/

“Creativity and innovation took many forms during the sixth century B.C. The earliest known Greek scientist, Thales of Miletos, demonstrated the cycles of nature and successfully predicted a solar eclipse and the solstices. Pythagoras of Samos, famous today for the theorem in geometry that bears his name, was an influential and forward-thinking mathematician. In Athens, the lawgiver and poet Solon instituted groundbreaking reforms and established a written code of laws. Meanwhile, potters (both native and foreign-born) mastered Corinthian techniques in Athens and by 550 B.C., Athenian—also called "Attic" for the region around Athens—black-figure pottery dominated the export market throughout the Mediterranean region. Athenian vases of the second half of the sixth century B.C. provide a wealth of iconography illuminating numerous aspects of Greek culture, including funerary rites, daily life, symposia, athletics, warfare, religion, and mythology. Among the great painters of Attic black-figure vases, Sophilos, Kleitias, Nearchos, Lydos, Exekias, and the Amasis Painter experimented with a variety of techniques to overcome the limitations of black-figure painting with its emphasis on silhouette and incised detail. The consequent invention of the red-figure technique, which offered greater opportunities for drawing and eventually superseded black-figure, is conventionally dated about 530 B.C. and attributed to the workshop of the potter Andokides. \^/

Art from Archaic-Period Sparta

Contrasting the austerity of Sparta (Lacedaemon) to the rich artistic scene in Athens, Thucydides wrote at the end of the fifth century B.C. in “The Peloponnesian War,” Book 1:1:“I suppose if Lacedaemon (Sparta) were to become desolate, and the temples and the foundations of the public buildings were left, that as time went on there would be a strong disposition with posterity to refuse to accept her fame as a true exponent for her power. … [A]s the city is neither built in a compact form nor adorned with magnificent temples and public edifices, but composed of villages, after the old fashion of Hellas, there would be an impression of inadequacy. Whereas, if Athens were to suffer the same misfortune, I suppose that any inference from the appearance presented to the eye would make her power to have been twice as great as it is."

Spartan pottery from around 500 BC

“Painted pottery was produced in Laconian workshops already in the eighth century B.C., in a local version of the Geometric style, and circulated to most regions and centers of the Greek world. After the mainly nonfigural decoration of the Orientalizing period, around 630 B.C., Laconian vase painters adopted the black-figure technique from Corinth, at about the same time the more famous and important Athenian black-figure style began. Although it cannot be compared to the Athenian in quantity and in artistic invention, Laconian black-figure vase painting produced a characteristic style and reached even remote regions of the Mediterranean, beyond the boundaries of the Greek world. Its heyday coincides roughly with the second and third quarters of the sixth century B.C., when five leading masters and some lesser painters were active. The most popular pottery shape was a local variant of the kylix (a rather shallow, two-handled drinking cup on a more or less tall stem), usually decorated with a figural scene in the tondo and with ornamental rows and compact black bands on the exterior. In the tondos, mythological subjects are frequent, alternating with scenes from real life, which, however, always bear a heroic connotation. Laconian black-figure painters had a predilection for special variations on conventional mythological scenes, symbolic figures like winged human figures, sirens, and sphinxes, and floral ornamental patterns including pomegranates and tendrils . A specific Laconian vase shape is the lakaina, which, however, was never decorated with figural scenes. Laconian pottery was widely distributed in the Greek East (Samos, Rhodes), in North Africa, where part of the Greek population claimed Spartan origins (Naucratis, Cyrene), in Southern Italy (where Taras, the only city-state founded by Spartans in the West, could play a role as a center of distribution), Sicily, and Etruria. It can be argued that the representation of myth and life seen on Laconian vases also inspired some local artistic creations in the Greek West and in Etruria. \^/

“The Spartan sanctuary of Artemis Orthia is also the find-spot of other unusual series of votive offerings, among which are the curious tiny lead relief-figurines, representing a winged goddess , a variety of human figures, and different kinds of animals. \^/

“Literary sources confirm that in the sixth century B.C., Sparta was also a major artistic center and home to several important artists and workshops. Some of the artists may have been immigrants, mainly of East Greek origin, such as Bathykles of Magnesia, whose elaborate "throne" of Apollo in Amyclae is described in detail by Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 3: 18.6–19.5). Others seem to have been born and educated in Sparta, such as Gitiadas, creator of the cult statue of Athena Chalkioikos and of prestigious votive gifts to Artemis in Amyclae (Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 3:18.7 and 4:14.2). While these works of art, however famous in late antiquity, are now lost, we can rely on some extant stone sculptures for an idea of Laconian large-scale art: such works include the Archaic Spartan hero reliefs, especially the monumental piece found in Chrysapha, and an early sixth-century B.C. female head in Olympia, which can be connected with Sparta on firm stylistic grounds. \^/

“In the second half and particularly in the last quarter of the sixth century B.C., Laconian crafts declined in quantity and quality. Laconian painted pottery was driven out of its old markets by Athenian exports. There were still remarkable achievements in bronze statuary, as evinced by a hollow-cast bronze statue head in Boston, but gradually Laconian artists abandoned the characteristic stylistic traits of the region and adopted more generic conventions of Late Archaic Greek art.” \^/

Bronze Art from Archaic-Period Sparta

Agnes Bencze and Péter Pázmány wrote: “An outstanding field of Laconian art and craft was bronzeworking, in particular small-scale bronze sculpture and the production of decorated bronze vessels. Solid cast, small-scale bronze figures usually embellished vessels, tripods, mirrors, and other utensils; however, isolated pieces found in sanctuaries could also have been votive offerings on their own. A characteristic Spartan figural type can already be recognized in the eighth century B.C. in the representation of horses, a widespread subject in early Greek small-scale bronze sculpture: among these extremely abstract renderings of the late Geometric period, a large number of statuettes found in Laconia and in the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia can be ascribed to Laconian craftsmen. [Source: Agnes Bencze, Department of Art History, Péter Pázmány Catholic University, Budapest, June 2014, metmuseum.org \^/]

Spartan woman

“Towards the end of the seventh century B.C., Laconian bronzeworkers began to produce magnificent decorated vessels and other artistic objects. The greatest assets of Laconian workshops are large kraters (mixing bowls) and smaller hydriai (water jars), made by hammering and decorated with solid cast figures, ranging from floral ornaments and snakes to animal and human protomes and mythological figures. Vertical handles can assume the shape of a human figure; in other cases, mainly on the earlier pieces, we find a pair of lions or the face of a goddess at the base of a handle or below the rim. Laconian bronze vessels are distinguished essentially on stylistic grounds from contemporary Corinthian, Argive, Athenian, and other products, taking into account both the shape and technical traits of the vessels themselves and the rendering of the figural decoration. One particular class of bronze objects can be entirely ascribed to Sparta on the account of their special iconography: disk-shaped mirrors supported by figures of nude girls. The subject of naked women is extremely rare in archaic Greek art, but the conspicuously young, almost childish female figure, naked except for a series of ritual attributes, can be plausibly ascribed to Laconia, where the local cult of Artemis Orthia may have inspired this unusual iconography. Sometimes Spartan mirrors of this type were exported as well, with examples from as far away as Cyprus. \^/

“Laconian bronze artifacts were especially popular in the West: they were not only exported to Southern Italy, Sicily, and Central Italy, but also inspired important local productions of bronze artifacts. While in the case of painted pottery, imports and local imitations can be distinguished rather clearly, the same task becomes extremely complicated with bronzes. In fact, decorated bronze artifacts were prestigious goods and traveled along different itineraries than pottery, reaching sometimes surprisingly distant destinations. Craftsmen specialized in this art could travel more easily, following commissions to remote regions. They could settle down in new places and found new workshops whose stylistic and iconographic repertory could derive at least partly from the tradition of their founders. For this reason, often fine bronzes are tentatively ascribed to a Spartan workshop, although discovered in Italy, or even beyond, in France or Central Europe. However, these attributions are subject to long debates, sometimes without a real possibility of conclusion. This problem is particularly evident in Southern Italy, where a number of bronze artifacts show characteristic traits that recall the Laconian tradition, nevertheless they cannot be ascribed to Sparta with certainty. A famous example is an elaborate tripod found in Metaponto.” \^/

Art of Classical Greece (ca. 480–323 B.C.)

classical style krater

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “After the defeat of the Persians in 479 B.C., Athens dominated Greece politically, economically, and culturally. The Athenians organized a confederacy of allies to ensure the freedom of the Greek cities in the Aegean islands and on the coast of Asia Minor. Members of the so-called Delian League provided either ships or a fixed sum of money that was kept in a treasury on the island of Delos, sacred to Apollo. With control of the funds and a strong fleet, Athens gradually transformed the originally voluntary members of the League into subjects. By 454/453 B.C., when the treasury was moved from Delos to the Athenian Akropolis, the city had become a wealthy imperial power. It had also developed into the first democracy. All adult male citizens participated in the elections and meetings of the assembly, which served as both the seat of government and a court of law. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, January 2008, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Perikles (r. ca. 461–429 B.C.), the most creative and adroit statesman of the third quarter of the fifth century B.C., transformed the Akropolis into a lasting monument to Athen's newfound political and economic power. Dedicated to Athena, the city's patron goddess, the Parthenon epitomizes the architectural and sculptural grandeur of Perikles' building program. Inside the magnificent Doric temple stood the colossal gold-and-ivory statue of Athena made by the Greek sculptor Pheidias. The building itself was constructed entirely of marble and richly embellished with sculpture, some of the finest examples of the high Classical style of the mid-fifth century B.C. Its sculptural decoration has had a major impact on other works of art, from the fifth century B.C. through the present day. \^/

“Greek artists of the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. attained a manner of representation that conveys a vitality of life as well as a sense of permanence, clarity, and harmony. Polykleitos of Argos was particularly famous for formulating a system of proportions that achieved this artistic effect and allowed others to reproduce it. His treatise, the Canon, is now lost, but one of his most important sculptural works, the Diadoumenos, survives in numerous ancient marble copies of the bronze original. Bronze, valued for its tensile strength and lustrous beauty, became the preferred medium for freestanding statuary, although very few bronze originals of the fifth century B.C. survive. What we know of these famous sculptures comes primarily from ancient literature and later Roman copies in marble. \^/

“The middle of the fifth century B.C. is often referred to as the Golden Age of Greece, particularly of Athens. Significant achievements were made in Attic vase painting. Most notably, the red-figure technique superseded the black-figure technique, and with that, great strides were made in portraying the human body, clothed or naked, at rest or in motion. The work of vase painters, such as Douris, Makron, Kleophrades, and the Berlin Painter, exhibit exquisitely rendered details. \^/

Elgin Marbles horsemen

“Although the high point of Classical expression was short-lived, it is important to note that it was forged during the Persian Wars (490–479 B.C.) and continued after the Peloponnesian War (431–404 B.C.) between Athens and a league of allied city-states led by Sparta. The conflict continued intermittently for nearly thirty years. Athens suffered irreparable damage during the war and a devastating plague that lasted over four years. Although the city lost its primacy, its artistic importance continued unabated during the fourth century B.C. The elegant, calligraphic style of late fifth-century sculpture was followed by a sober grandeur in both freestanding statues and many grave monuments. One of the far-reaching innovations in sculpture at this time, and one of the most celebrated statues of antiquity, was the nude Aphrodite of Knidos, by the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles. Praxiteles' creation broke one of the most tenacious conventions in Greek art in which the female figure had previously been shown draped. Its slender proportions and distinctive contrapposto stance became hallmarks of fourth-century B.C. Greek sculpture. In architecture, the Corinthian—characterized by ornate, vegetal column capitals—first came into vogue. And for the first time, artistic schools were established as institutions of learning. Among the most famous was the school at Sicyon in the Peloponnese, which emphasized a cumulative knowledge of art, the foundation of art history. Greek artists also traveled more extensively than in previous centuries. The sculptor Skopas of Paros traveled throughout the eastern Mediterranean for his commissions, among them the Mausoleum at Halicarnassos, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. \^/

“While Athens began to decline during the fourth century B.C., the influence of Greek cities in southern Italy and Sicily spread to indigenous cultures that readily adopted Greek styles and employed Greek artists. Depictions of Athenian drama, which flourished in the fifth century with the work of Aeschylus, Sophokles, and Euripides, was an especially popular subject for locally produced pottery. \^/

“During the mid-fourth century B.C., Macedonia (in northern Greece) became a formidable power under Philip II (r. 360/59–336 B.C.), and the Macedonian royal court became the leading center of Greek culture. Philip's military and political achievements ably served the conquests of his son, Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 B.C.). Within eleven years, Alexander subdued the Persian empire of western Asia and Egypt, continuing into Central Asia as far as the Indus River valley. During his reign, Alexander cultivated the arts as no patron had done before him. Among his retinue of artists was the court sculptor Lysippos, arguably one of the most important artists of the fourth century B.C. His works, most notably his portraits of Alexander (and the work they influenced), inaugurated many features of Hellenistic sculpture, such as the heroic ruler portrait . When Alexander died in 323 B.C., his successors, many of whom adopted this portrait type, divided up the vast empire into smaller kingdoms that transformed the political and cultural world during the Hellenistic period.

Art from Hellenistic Period (323-31 B.C.)

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Between 334 and 323 B.C., Alexander the Great and his armies conquered much of the known world, creating an empire that stretched from Greece and Asia Minor through Egypt and the Persian empire in the Near East to India. This unprecedented contact with cultures far and wide disseminated Greek culture and its arts, and exposed Greek artistic styles to a host of new exotic influences. The death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C. traditionally marks the beginning of the Hellenistic period. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

Nike of Samothrace

“Alexander's generals, known as the Diadochoi, that is, "successors," divided the many lands of his empire into kingdoms of their own. New Hellenistic dynasties emerged—the Seleucids in the Near East, the Ptolemies in Egypt, and the Antigonids in Macedonia. However, some Greek city-states asserted their independence through alliances. The most important of such alliances between several city-states were the Aitolian League in western central Greece and the Achaian League based in the Peloponnese. \^/

“During the first half of the third century B.C., smaller kingdoms broke off from the vast Seleucid kingdom and established their independence. Northern and central Asia Minor was divided into the kingdoms of Bithynia, Galatia, Paphlagonia, Pontus, and Cappadocia. Each of these new kingdoms was ruled by a local dynasty lingering from the earlier Achaemenid Persian empire, but infused with new, Greek elements. The Attalid royal family of the great city-state of Pergamon reigned over much of western Asia Minor, and an influential dynasty of Greek and Macedonian descent ruled over a vast kingdom that stretched from Bactria to the Far East. In this greatly expanded Greek world, Hellenistic art and culture emerged and flourished. \^/

“Hellenistic kingship remained the dominant political form in the Greek East for nearly three centuries following the death of Alexander the Great. Royal families lived in splendid palaces with elaborate banquet halls and sumptuously decorated rooms and gardens. Court festivals and symposia held in the royal palaces provided opportunities for lavish displays of wealth. Hellenistic kings became prominent patrons of the arts, commissioning public works of architecture and sculpture, as well as private luxury items that demonstrated their wealth and taste. Jewelry, for example, took on new elaborate forms and incorporated rare and unique stones. New precious and semiprecious stones were available through newly established trade routes. Concurrently, increased commercial and cultural exchanges, and the greater mobility of goldsmiths and silversmiths, led to the establishment of a koine (common language) throughout the Hellenistic world. \^/

“Hellenistic art is richly diverse in subject matter and in stylistic development. It was created during an age characterized by a strong sense of history. For the first time, there were museums and great libraries, such as those at Alexandria and Pergamon. Hellenistic artists copied and adapted earlier styles, and also made great innovations. Representations of Greek gods took on new forms. The popular image of a nude Aphrodite, for example, reflects the increased secularization of traditional religion. Also prominent in Hellenistic art are representations of Dionysos, the god of wine and legendary conqueror of the East, as well as those of Hermes, the god of commerce. In strikingly tender depictions, Eros, the Greek personification of love, is portrayed as a young child. \^/

Hellenistic Sculpture

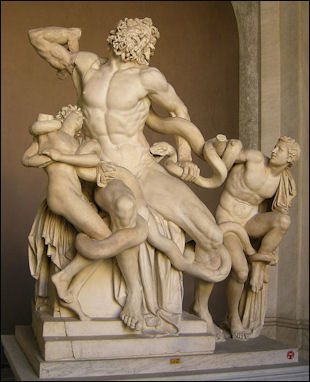

Apollo Belvedere Hellenistic Sculpture (323 B.C. to 31 B.C.) was much more varied and extreme than sculpture produced during the Classical period. Some of the most beautiful pieces of Greek statuary, including the “ Nike of Samonthrace, the Dying Gaul, Apollo Belvedere” , and the “ Lacoön Group,” date back to Hellenistic times. “The Dying Gual” has the hair and facial features of an ethnic Gaul.

The Lacoon, now at Vatican Museum, features a father and two sons struggling to entangle themselves from the grasps of giant serpents. The 2000-year-old statue depicts the punishment meted out to a priest who warned the Trojans to beware of Greeks bearing gifts.

Adam Masterman, wrote in Quora.com: During the Hellenistic period (323031 B.C.) sculpture fully embraced naturalism. Figures look like individuals instead of ideals, and a full range of emotions and actions are portrayed. Poses are the most diverse of any of the periods, representing a wide variety of actions and physical states. The anatomical detail is the most closely resembling real bodies (and thus the least idealized), and particular attention is paid to how bodies morph and change in different positions, showing a strong tradition of empirical observation. Finally, the work is more ornate than in any other period, reflecting a preference for complexity of design that can also be seen in the architecture of the time.

“Apollo Belvedere” , also at the Vatican Museum, glorifies the male body. Described by one critic as "a symbol of all that is young and free strong and gracious," it is most likely a Roman copy of a Greek bronze made by Leochares around 330 B.C. The original once stood in the Agora in Athens but is now lost. The copy lacks its left hand and most of its straight arm and scholars believe the right hand held a quiver and the left hand a bow. The elegant cloak is still in place. For several centuries it had a fig leaf over private parts.

“Apollo Belvedere” stood for four centuries in a niche in the Octagonal court of the Vatican until it was taken by Napoleon's army in 1798 and kept in Paris until 1816, when it was returned. It was said Napoleon that coveted it more than any other booty because it was considered the embodiment of the high culture of classical Greece.

“ Nike of Samonthrace”, at the Louvre, is considered one of the greatest masterpieces of Greek art. Wings spread wide into a headwind that blows her clothes against her headless body, an image that later would grace the bow of many ships. see the Louvre

Venus de Milo

Venus de Milo ”The Venus de Milo” is arguable the world’s most famous sculpture and may be the second most famous work of art after the “Mona Lisa”. Thousands check it out daily in the Louvre, where it has stood for more than a century. It has been sketched, copied, debased and lampooned, Among the artists who have been inspired by it and/or placed it in their own works have been Cezanne, Dail and Magritte but at the same time it has been debased in advertisement and kitschy souvenirs . When she came to Japan in 1964 more than 100,000 people came to greet the ship that carried her and 1.5 million filed past on a moving sidewalk that ran past where she was displayed. [Source: Gregory Curtis, Smithsonian magazine, October 2003]

The “Venus de Milo” was originally carved in two parts, with the two halves concealed by the fold of drapery circling her hips. The pedestal and the arms have been lost. No one is sure how the arms were posed. Some believe the upraised arm rested on a pillar. Others believe it may have held a shield. Yet others believe it may have held an apple found near the statue.

After the statue was brought to the Louvre restorers tried to attach plaster arms in all conceivable positions — carrying robes, apples and lamps or just painting here and there. None of which looked right. It was thus decreed that the "work of another artist must never mar her beauty" which set a worldwide precedent. From then on classical works of art were never monkeyed with again.

The Venus de Milo was found in 1820 by a peasant in a cave on Melos, a Greek island in the Aegean Sea about halfway between Crete and the Greek mainland (her name means “Venus of Melos”). It was then claimed by French archaeologists and bought by French officials for the relatively paltry sum of 1,000 francs, which was paid to the Ottoman Turkish overlords of Greece. After it was displayed the Germans claimed the statue was there as it was unearthed on land purchased by Crown Prince Ludwig I of Bavaria in 1917.

Sculpted around 100 B.C., the Venus de Milo was found in two parts, along with pieces of the arms and a pedestal. The French originally thought it was made by the master Phidias or Praxiteles, until it was discovered it was inscribed with the name “Alexandros, son of Menides, from the city of Antioch on the Meander". Compounding the disappointments was the fact it was produced after the classical period (statues made in the Hellenistic period were considered inferior to those made in the classical period). Not to worry the base with the name on it was simply made to disappear. However drawings made when the base was still in existence and the debate on whether it was a classical piece or not entered the dispute between France and Germany as to who owned. To this day the Louvre remains a little embarrassed by the whole issue.

Early in the 20th century reference to Alexandros of Antioch were found in Thespiae, a city near Mount Helicon on the mainland of Greece. It turns that Alexandros was more than just a sculptor. An inscription dated to 80 B.C. identifies Alexandros of Antioch, son of Menides as the winner of a singing and composing competition.

Impact of Hellenistic Period Art (323-31 B.C.)

The Laocoon According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: ““One of the immediate results of the new international Hellenistic milieu was the widened range of subject matter that had little precedent in earlier Greek art. There are representations of unorthodox subjects, such as grotesques, and of more conventional inhabitants, such as children and elderly people. These images, as well as the portraits of ethnic people, especially those of Africans, describe a diverse Hellenistic populace. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

“A growing number of art collectors commissioned original works of art and copies of earlier Greek statues. Likewise, increasingly affluent consumers were eager to enhance their private homes and gardens with luxury goods, such as fine bronze statuettes, intricately carved furniture decorated with bronze fittings, stone sculpture, and elaborate pottery with mold-made decoration. These lavish items were manufactured on a grand scale as never before. \^/

“The most avid collectors of Greek art, however, were the Romans, who decorated their town houses and country villas with Greek sculptures according to their interests and taste. The wall paintings from the villa at Boscoreale, some of which clearly echo lost Hellenistic Macedonian royal paintings, and exquisite bronzes in the Metropolitan Museum's collection testify to the refined classical environment that the Roman aristocracy cultivated in their homes. By the first century B.C., Rome was a center of Hellenistic art production, and numerous Greek artists came there to work. \^/

“The conventional end of the Hellenistic period is 31 B.C., the date of the battle of Actium. Octavian, who later became the emperor Augustus, defeated Marc Antony's fleet and, consequently, ended Ptolemaic rule. The Ptolemies were the last Hellenistic dynasty to fall to Rome. Interest in Greek art and culture remained strong during the Roman Imperial period, and especially so during the reigns of the emperors Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–14 A.D.) and Hadrian (r. 117–138 A.D.). For centuries, Roman artists continued to make works of art in the Hellenistic tradition.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2018