Home | Category: Art and Architecture

ANCIENT GREEK ART

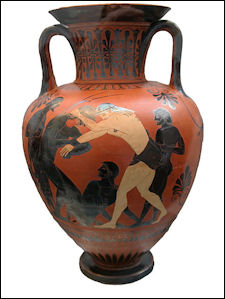

vase with Greek athlete Art from ancient Greece and Rome is often called classical art. This is a reference to the fact that the art was not only beautiful and of high quality but that it came from a Golden Age in the past and was passed down to us today. Greek art influenced Roman art and both of them were an inspiration for the Renaissance

The Greeks have been described as idealistic, imaginative and spiritual while the Romans were slighted for being too closely bound to the world they saw in front of them. The Greeks produced the Olympics and great works of art while the Romans devised gladiator contests and copied Greek art. In “Ode on a Grecian Urn” , John Keats wrote: "Beauty is truth, truth beauty, “that is all/ Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

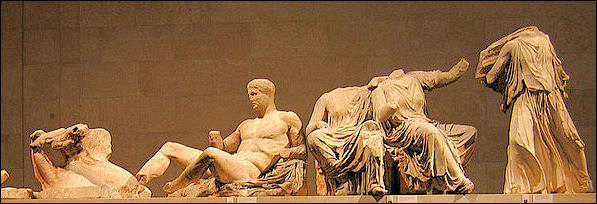

Greece reached its zenith during the Golden Age of Athens (457 B.C. to 430 B.C.) when great temples were built in Athens and Olympia and they were decorated with wonderful sculptures and reliefs. Hellenistic arts imitated life realistically, especially in sculpture and literature.

Greek artists identified themselves for the first time in the eight century B.C., when pottery painting contained statements such as "Ergotimos made me" and "Kletis painted me."

Fortunately the artistic production of the ancient Greeks was extensive enough that even though most of it has now been lost enough remains in form of originals, fragments and copies that we are able to appreciate it not only in terms of quantity but its quality. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

Minoan and Mycenaean Art, See Minoans and Mycenaeans Under History

Websites on Ancient Greece: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; The Ancient City of Athens stoa.org/athens; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ;Ancient-Greek.org ancientgreece.com;Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Classical Art: From Greece to Rome (Oxford History of Art) by Mary Beard, John Henderson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

“Greek Art” (World of Art) by John Boardman (1964) Amazon.com;

“A History of Greek Art” by Mark Stansbury-O'Donnell (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Classical Tradition in Art” by Michael Greenhalgh, (1982) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Greece and Rome, From the Rise of Greece to the Fall of Rome”

by Giovanni Becatti (1967) Amazon.com;

“The Art and Archaeology of Ancient Greece” by Judith M Barringer Amazon.com;

“Archaic and Classical Greek Art” (Oxford History of Art) by Robin Osborne (1998) Amazon.com;

“Hellenistic Art: From Alexander the Great to Augustus” by Lucilla Burn (2005) Amazon.com;

“Defining Beauty: the Body in Ancient Greek Art: Art and Thought in Ancient Greece”

by Ian Jenkins (2015) Amazon.com;

“Esthetic Basis of Greek Art” by Rhys Carpenter (1921) Amazon.com;

“Beauty: The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea” by David Konstan (2017)

Amazon.com;

“Images of Myths in Classical Antiquity” by Susan Woodford (2003) Amazon.com;

“Life, Myth, and Art in Ancient Greece” by Emma Stafford (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Greece; Sources and Documents” by Jerome J. Pollitt (1990) Amazon.com;

“Art and Experience in Classical Greece” by Jerome J. Pollitt (1972) Amazon.com;

“Greek & Roman Art” (Art Essentials) by Susan Woodford (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Greece” by Sabine Albersmeier |(2008) Amazon.com;

“Greek Art A&I” (Art and Ideas) by Nigel Spivey (1997) Amazon.com;

Ancient Greek View of Art as a Trade

5th century BC psykter Modern perspectives on what constitutes art and our clear distinctions between artists and craftspeople differ from the practice in ancient Greece. The Greeks did not have muses charged with responsibility for art and sculpture as they did for literature, music and dance. Indeed they did not have a word for “art” in their language using the word tekhne which translates as “craft”. Sculpture, pottery, metalwork and the creation of frescoes, mosaics and wall paintings fell into the realm of tekhne. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

This attitude was often reflected in Greek wage scales and we see in accounting records where the architect of a major temple and a stonemason working on the same structure received essentially equivalent wages. That is not to say that their craftsmen weren’t held in high regard and that there wasn’t a generally recognized distinction between journeymen artisans and those whose skills had earned them greater prestige and esteem. Alexander, the Great insisted that busts of him be executed only by the renowned sculptor Lycippus and that paintings of him (e.g. Alexander, with thunderbolt) be done by the equally-famous Apelles. |

“Greeks with aristocratic roots looked upon any kind of manual labour with distaste. That certainly included sculpture, pottery and metalwork. Aristotle, enlightened in many ways, wrote that the title of “citizen” should be withheld from all those who earned their living with their hands, that it wasn’t possible to practice the civic virtues as a salaried worker. Others who expressed a similar view included Plato and Xenophon (but not Socrates who saw merit in honest labour and who practiced what he preached.)

“The law-giver Solon notes that no well-bred young man could possibly want to be a sculptor and the pejorative word banausos was used to designate workers in at least some of the craft areas. This Athenian attitude, in a city admired for its art and beauty, is paradoxical and was not universal throughout ancient Greece. In many cities, particularly those with an industrial or commercial focus, the word cheironax was used to denote “master craftsmen” and these people were accorded honour and respect. |

Nudes in Greco-Roman Art

Apollo Belvedere

Jean Sorabella wrote for the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The nude first became significant in the art of ancient Greece, where athletic competitions at religious festivals celebrated the human body, particularly the male, in an unparalleled way. The athletes in these contests competed in the nude, and the Greeks considered them embodiments of all that was best in humanity. It was thus perfectly natural for the Greeks to associate the male nude form with triumph, glory, and even moral excellence, values which seem immanent in the magnificent nudes of Greek sculpture (25.78.56). Images of naked athletes stood as offerings in sanctuaries, while athletic-looking nudes portrayed the gods and heroes of Greek religion. The celebration of the body among the Greeks contrasts remarkably with the attitudes prevalent in other parts of the ancient world, where undress was typically associated with disgrace and defeat. The best-known example of this more common view is the biblical story of Adam and Eve, where the first man and woman discover that they are naked and consequently suffer shame and punishment. [Source: Jean Sorabella, Independent Scholar, Metropolitan Museum of Art, January 2008, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The ancestry of the female nude is distinct from the male. Where the latter originates in the perfect human athlete, the former embodies the divinity of procreation. Naked female figures are shown in very early prehistoric art, and in historical times, similar images represent such fertility deities as the Near Eastern Ishtar. The Greek goddess Aphrodite belongs to this family, and she too was imagined as life-giving, proud, and seductive. For many centuries, the Greeks preferred to see her clothed, unlike her Near Eastern counterparts, but in the mid-fourth century B.C., the sculptor Praxiteles made a naked Aphrodite, called the Knidian, which established a new tradition for the female nude. Lacking the bulbous and exaggerated forms of Near Eastern fertility figures, the Knidian Aphrodite, like Greek male athletic statues, had idealized proportions based on mathematical ratios. In addition, her pose, with head turned to the side and one hand covering the body, seemed to present the goddess surprised in her bath and thus fleshed the nude with narrative and erotic possibilities. The position of the goddess' hands may be meant to show modesty or desire to shield the viewer from too full a view of her godhead. Although the Knidian statue is not preserved, its impact survives in the numerous replicas and variants of it commissioned in the Hellenistic (12.173) and Roman (52.11.5) eras. Such images of Venus (the Latin name of Aphrodite) adorned houses, bath buildings, and tombs as well as temples and outdoor sanctuaries. \^/

“Since the nudes of ancient Greece and Rome became normative in later Western art, it is worth pausing to consider what they are and are not. They express profound admiration for the body as the shape of humanity, yet they do not celebrate human variety; they may have sex appeal, yet they are never totally prurient in intent. The nudes of Greco-Roman art are conceptually perfected ideal persons, each one a vision of health, youth, geometric clarity, and organic equilibrium. Kenneth Clark considered idealization the hallmark of true nudes, as opposed to more descriptive and less artful figures that he considered merely naked. His emphasis on idealization points up an essential issue: seductive and appealing as nudes in art may be, they are meant to stir the mind as well as the passions.

Ancient Greek Painting

painting of animal sacrifice from 6th century BC Corinth

Virtually no Greek paintings or murals have survived until the 20th century. Most of the what we know is based on written descriptions. The paintings that have survived are mostly those on vases that were made during the Archaic Age (750 B.C. to 500 B.C.) not during the Golden Age of Greece (457 B.C. to 430 B.C.).

Greeks used pigments mixed with hot wax to paint their warships. Later the Romans used this technique to make portraits. The Greeks also used paints made from precious stones, earth and plants. The Aristotelean beliefs that all colors were created by mixing black and white endured until the 17th century.

The ancient Mediterraneans obtained blue from a hermaphroditic snail with a gland that produces a fluid that becomes blue when exposed to air and light. The glands only produced the stuff when they were more male than female.

Subjects of ancient Greek paintings include snake-haired Medusas, centaurs, dancing girls, Olympic athletes and gods. A Greek tomb painting from the fifth century B.C. shows an athlete diving from one world to the next.

The Greek painter Zeuxis laughed so hard at one of his own paintings he broke a blood vessel and died.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK PAINTING europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Greek Sculpture

The Greeks were master sculptors. They were much more highly skilled than the Egyptians that preceded them and the Romans who came afterwards. Their skill and sense of aesthetics was not matched until the Renaissance. Describing a Greek statue of Hercules, Cicero wrote: "I do not know that I have ever seen a lovelier work of art." Its mouth and chin were rubbed, he said, as if the people had not only prayed to it but kissed it.

Athletes were favorite subjects. Fearing the establishment of personality cults, sculptors focused in on the physique and idealized physical features of the athletes they depicted. They did not, except in rare cases, attempt to create individualized portraits. We hardly know any of the names of the artists on most Greek works of art. In the case a sculpture when a work was identified with a name it is not clear whether the name is of a person who did the work by himself or if he was assisted by a school or workshop.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK SCULPTURE: MATERIALS, COLORS, FORMS AND SCULPTING TECHNIQUES europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Greek Pottery

8th century BC jug Ceramics created by the Greeks were far superior to anything made by civilizations that preceded it. The Greeks produced vases, urns and bowls. They were known for their craftsmanship. The most famous pieces were vases with paintings such as Apollo playing a tortoise shell lyre. Unlike oriental pottery which came in all kinds of shapes, ancient Greek pottery was more limited, comprised of only a few dozen shapes that changed little over time.

Many things — including grain, olive oil or wine — were stored and carried amphorae (large clay jars) with two handles near the mouth that made it possible to pick them up and carry them. They generally were two to three feet tall and carried about seven gallons. Their shapes and markings were unique and these helped archaeologists date them and identify their place of origin.

Most Greek pottery was connected with wine. Large two-handled amphorae (from the Greek “ amphi” , “on both sides,” and “ phero” , “to carry”) was used to transport wine. Smaller, flat bottom amphorae were used to hold wine on the table. Kraters were amphora-like vessels with a wide mouth used to mix water and wine. From a krater wine and water were retrieved with a metal ladle and placed into pitcher and from the pitcher poured into two-handled drinking cups.

Hydria, with two horizontal handles, were round jars used to carry water from a well to a fountain. Before glassblowing was developed in the 1st century B.C. “core glass” vessels were made by forming glass around a solid metal rod that was taken out as the glass cooled.

The largest ancient metal vessel ever found was bronze krater dated to the sixth century B.C. Found in the tomb of a Celtic warrior princess, it was buried with a chariot and other objects in a field near Vix, France. Almost as tall as a man and large enough to hold 300 gallons of wine, it had reliefs of soldiers and chariots around the neck and a bronze cover that fit snugly in the mouth. Ordinary amphora held only around a gallon of wine.

Pausanias on the Art in the Town of Amaklai

On “the interesting things at Amyklai”, a town in Laconia in southern Greece, six kilometers south of Sparta, Pausanias wrote in Periegesis Hellados III. 6 (A.D. 160): “There is a stone stele naming Ainetos a winner of the Pentathlon; he died, or so they say, with his head still wearing the wreath after winning at Olympia. There is a portrait of him, and there are bronze tripods. The older tripods are said to be a tithe of the spoils of the war against Messenia. Under the first tripod stands a statue of Aphrodite; under the second is Artemis; these tripods and their decorations are by Gitiadas. But the third tripod is by Kallon of Aegina, and under it stands a statue of Kore, Demeter's daughter. Aristandros of Paros made the Woman with the Harp, who is apparently "Sparta", and Polykleitos of Argos made the Aphrodite of the Amyklaians, as they call her. These tripods are larger than the others, which came from the Battle of Aegospotamoi. [Source: CSUN]

“Bathykles of Magnesia, who made the Throne of the Amyklaian, dedicated the Graces when he had completed it, along with a statue of Artemis of Good Thoughts. The question as to who taught Bathykles and under which Spartan king he worked is one which I leave aside, but I saw the Throne, and I will describe it. In front of it and behind it rise two Graces and two Seasons; on the left stand Echidna and Typhoeus, while on the right there are Tritons. It would weary my readers if I went through all the workmanship in detail; but, to summarize (since most of it is familiar anyway), Poseidon and Zeus are carrying Taygete, the daughter of Atlas, and her sister Alkyone. Atlas is also carved on it, and the fight of Herakles and Cyknos, and the battle of the Centaurs in the Cave of Pholos. I do not understand why Bathykles carved the Minotaur, bound and taken alive by Theseus. There is a Phaeacean dance on the Throne, and Demodokos is singing. There is Perseus, triumphing over Medusa. There is the carrying off the daughters of Leukippos, the fight between Herakles and the giant Thourios, and the fight between Tyndareus and the giant Eurytos. Hermes is carrying the infant Dionysos to Olympus, and Athena is bringing Herakles to live with the gods forever. Peleus is handing over Achilles to be brought up by Cheiron, since Achilles is said to have been one of his pupils. Kephalos is being carried off by Eos because of his beauty. The gods are bringing gifts to the wedding of Harmonia. There are images of the combat of Achilles with Memnon, and Herakles punishing Diomedes the Thracian, and Nessos in the River Euenos. Hermes is taking the goddesses to be judged by Paris. Adrastos and Tydeus break up the fight between Amphiaraos and Lykourgos, son of Pronax. Hera is looking at Io, daughter of Inachos, who has been turned into a heifer. Athena is escaping from Hephaestus, who is pursuing her. Then there is the series of the great deeds of Herakles: Herakles and the Hydra, and Herakles bringing back the Hound of Hades. Anaxias and Mnasinous are each on horseback, but Megapenthes the son of Menelaus and Nikostratos share a horse. Bellerophon is destroying the Lycian monster; Herakles is driving off the cattle of Geryon.

Altar of Zeus from Pergamon

“At the upper limits of the Throne are the sons of Tyndareus on horseback, one on either side; here are sphixes under the horses and wild beasts with their heads raised, a lioness under Polydeukes and a leopard on the other side. On the very top of the throne is the dance of the Magnesians, who worked on the Throne with Bathykles. Underneath the throne, behind the Tritons, there is the Calydonian Boar Hunt, Herakles killing the sons of Aktor, Kalais and Zetes driving off the Harpies from Phineus, Perithoos and Theseus carrying off Helen, Herakles with the lion by the throat, and Apollo and Artemis shooting Tityos. There are carvings of Herakles fighting the Centaur Oreios and Theseus fighting the Minotaur, the wrestling match of Herakles and Acheloos, the story of Hera bound by Hephaestus, the games given by Akastos for his father, the story of Menelaus and Proteus the Egyptian (from the Odyssey. Finally, Admetus is harnessing his chariot with a boar and a lion, and the Trojans are bringing jars to offer them to Hektor.

“The part of the Throne where the god would sit is not a single continuous thing, but has several seats with a space next to each seat. The middle part is very broad, and that is where the statue stands. I know no one who has measured this, but at a guess you could say that it was forty-five feet. It is not the work of Bathykles, but ancient and made without artistry. Except for the face and the tips of its feet and hands it looks like a bronze pillar. It has a helmet on its head, and a spear and a bow in its hands. The base of the statue is shaped like an altar, and Hyakinthos is said to be buried in it. At the Hyakinthia, before the sacrifice to Apollo, they pass through a bronze door to dedicate the offerings of a divine hero to Hyakinthos in this altar; the door is on the left of the altar. There is a figure of (B)iris carved on one side of the altar, and Amphitrite and Poseidon on the other; Zeus and Hermes are talking together, with Dionysos and Semele standing nearby and Io beside Semele. Also on this altar are Demeter and Kore and Plouto, the Fates and the Seasons, and Aphrodite, Athena and Artemis (they are bringing Hyakinthos and Polyboia into Olympus; they say that she was his sister who died a virgin). In this sculpture, Hyakinthos has already grown hair on his face, but Nikias the son of Nikeratos had him painted as extremely beautiful, which is a reference to the fact that Apollo was in love with him. Herakles is also sculpted on this altar, being led into Olympus by Athena and all the gods. Then there are the daughters of Thestios, and the Muses and Seasons. The story of Zephyros, and how Hyakinthos was killed accidentally by Apollo, and the story of the flower, may not be true, but let it pass.”

Collection at the Greek National Archaeological Museum

The collection at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens is one of the best archeological museums in the world. The British may have taken the best the Parthenon had to offer but Greece has a lot of historical sites they missed and most outstanding stuff ended up here. In the center of the museum is the Mycenaean collection (circa 800 B.C.) which contains treasures taken from royal tombs including weapons, miniatures, stelae and cups from the famous Vafio beehive tomb.

On display from the so-called Agamemnon's beehive tomb are frescoes, gold jewelry and a golden mask which is believed to bear a likeness of Mycenaean commander who led the battle against Troy. Golden object from Mycenaean tombs including a lion helmet (1550 B.C), which looks like something from a science fiction movie. Classical Greek statues include a magnificent bronze of Poseidon casting a spear (which has been removed) and the standing youth. The exquisite bronze portrait head from Delos, with its sad longing eyes, made around 80 B.C., is one of the most expressive pieces of Greek sculpture.

In the Minoan collection (circa 900 B.C.) from Santorini is a collection of frescoes, vases and marble figurines taken from villages buried under volcanic ash. One 3500 year-old fresco shows two young boys in a boxing match, the first depiction of boxing gloves, or for that matter gloves of any kind. In another wing is a huge numismatic collection which contains some of the world's oldest coins.

The museum also contains sculptures of men with fish and a frescos of warships 20 feet long from Akrotiri, Santorini. two golden masks from Mycenae that don't belong to Argammenon, the tablets of Phylos with a chicken scratch written language that showed how the Greek language evolved from Mycenaean, and 44 pounds of gold treasure from the Mycenaean capital,

Minoan painting from Akrotiri

Collections at Other Museums in Greece

The Benaki Museum in Athens is a small museum with one of world's best collections of ancient gold objects. Founded in 1930 by collector Anthony Benaki, it contains a late-Archaic gold ring with an image of an archer, a 5th century B.C. gold bull-head pendant, a Hellenistic wreath fashioned from beaten gold “oak leaves,” a Hellenistic gold ring with an image of naked woman and a swan.

The Goulandris Museum of Cycladic and Ancient Greek Art (4 Neophytou Douka St) contains an extraordinary collection of 230 objects, including marble figurines from an isolated civilization that flourished 5,000 years ago on the Cyclades islands. Many of the figures have geometric oval faces with tubular noses that are reminiscent of some of Moor's work. The oldest pieces are violin-shaped stylized female torsos found in cemetery on Naxos that date back to 2800 B.C. Also worth checking out are the clay "frying pans" (whose function is unknown), a bronze hydria (three-handled water jug), and a jointed clay doll from Corinth with movable legs.

The Delphi Museum contains a life-size silver bull, the column of dancing girls and many stone carvings and monuments that once lined the sacred way. Also in the museum is a Roman replica of the sacred stone. The original stone, legend has its, was placed in Delphi by Zeus. To chose the site Zeus released one eagle from east and one eagle from the west. Where they met was where he threw the stone marking Delphi as "the navel of the world." The reconstruction of the Façade of the Treasury of the Siphnians feature a couple of draped women for columns and a frieze depicting “The Battle of the Gods and Giants” . Notice in particular that one of the lions pulling the chariot of Cybele is devouring one of the giants. The statue of a bronze charioteer is one of the earliest-known large bronze statues in Greek still in existence. Sculptors like bronze because they could lift up arms and defy gravity with more ease than with stone.

The Thessalonki Archeological Museum is regarded as the best archeological museum outside of Athens. It is comprised of classical treasures collected from all over northern Greece. Some of the best pieces are found in Vergina annex which houses items taken from the tomb of King Philip II, the father of Alexander the Great, which was excavated in 1977. There are also vases and bronze ornaments from the Geometric age; mosaic floors excavated in Thessalonki; and 1st century Roman sculptures including one of a empower who claimed his seat when he was 14.

There are two museums in Olympia: The archeological museum which contains a sculptures, pottery and bronze figures; and new museum which explains the history of the games and brings them to life. The main attraction at the Olympia Museum are sculptures of Hermes with a child and clothes in one hand, of Hippodamia attacked by a Centaur, and of Apollo.

Elgin Marbles, east pediment from the Parthenon

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum; Euphronious krater from New York Times; Alexandria funeral monument, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024