Home | Category: Literature and Drama

HOMER

Homer in the Musei Capitolini Homer is a person said to have written “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey”. He was the most important and earliest of the Greek and Roman writers. His influence was not only on literature, but ethics and morality as well. Homer is sometimes credited with the Homeric Hymns. However, scholars think these must have been written more recently than the Early Archaic period.

No one knows whether Homer was a he or she, or even a real person. The ancient Greeks believed he was a blind, itinerant bard who was born in Smyrna (present-day Izmir, Turkey) and lived in Chios (a Greek island near the coast of Turkey). Chios was famous for its epic singers and many people on the island called themselves “Homeridae” , the descendants of Homer. But these are far from universally-agreed-upon facts. Colophon, Salamis, Rhodes, Argos and Athens also claim to be his birthplace. There is no evidence that he was blind although a well-known bust of the poet suggests it.

Juan Piquero wrote in National Geographic: Homer's epics have been intriguing and entertaining audiences all over the world for centuries. From film to television, from page to stage, The Iliad and The Odyssey are well known for their riveting drama, fascinating characters, and timeless subjects and themes. These familiar stories have been studied and taught for centuries, but little is known about their author, the poet Homer. His birth date ranges between the 12th and eighth centuries B.C. Both The Iliad and The Odyssey are attributed to him, but he did not originate these stories. Many scholars believe that Homer may have been the first to write them down, an action which granted him fame that has endured for millennia. [Source: Juan Piquero, National Geographic, April 13, 2023]

The claim that Homer wrote the “Iliad” and “Odyssey” is traced to Herodotus. Homer is dated to about 850 B.C. because one Homeridae living in the 5th century said that Homer lived 400 years before him. Scholars believe the stories themselves evolved soon after the Trojan War, which took place about 1200 B.C., around the same time that Moses was leading the Jews to the Promised Land.

Both the Iliad and the Odyssey reveal a wealth of information about Greek society and cultural expression during the Dark Age. The description of the bronze armor of Achilles, the evolution of the Greek polis (city-state) and the detailed accounts of battles are all vividly written and visually evocative. They have the ring of truth about them. Although it may not be possible to extract solid historical data from Homer he certainly taught the world how the ancient Greeks thought and felt about themselves. [Source: Canadian Museum of History ]

RELATED ARTICLES:

HOMER'S TAKE ON TOPICS LIKE FOOD, SACRIFICES AND HADES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ILIAD: PLOT, CHARACTERS, BATTLES, FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HISTORICAL TROY: ARCHAEOLOGY, SITES, TROJAN WARS europe.factsanddetails.com l

ODYSSEY: PLOT, ODYSSEUS'S ADVENTURES AND THE CREATURES HE ENCOUNTERS europe.factsanddetails.com

REAL PLACES IN THE ODYSSEY, JAMES JOYCE AND THE SEARCH OF ODYSSEUS'S ITHACA europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece, Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Homer’s the Iliad and the Odyssey: A Biography” by Alberto Manguel (Atlantic Monthly, 2008) Amazon.com;

“Homer: The Very Idea” by James I. Porter Amazon.com;

“Homer: Poet of the Iliad” by Mark W. Edwards (1990) Amazon.com;

“The Iliad And The Odyssey of Homer” by Homer Amazon.com;

“Homeric Hymns” (Oxford World's Classics) Amazon.com;

“Homer and Mycenae” by Martin P. Nilsson (1933, 1968) Amazon.com;

“Homer's History: Mycenaean Or Dark Age?” by Carol. G. Thomas (1970) Amazon.com;

“From Hittite to Homer: The Anatolian Background of Ancient Greek Epic” by Mary R. Bachvarova (2016) Amazon.com;

“Greece in the Making (1200-479 BC)” by Robin Osborne (1996) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Archaic Greek World, ca. 1200-479 BCE” (Blackwell) by Jonathan M. Hall (2013) Amazon.com;

“From Mycenae to Homer: A Study in Early Greek Literature and Art” by T. B. L. Webster (1964) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Archaic Greece” by Kurt A. Raaflaub and Hans van Wees (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Coming of the Greeks” by Robert Drews Amazon.com;

“The Rise of the Greeks” by Michael Grant Amazon.com;

“The End of the Bronze Age” by Robert Drews (1995) Amazon.com;

“Militarism and the Indo-Europeanizing of Europe”

by Robert Drews Amazon.com;

“Last Mycenaeans, Their Successors: Archaeological Survey, 1200-1000 B.C.” by Vincent Desborough (1964) Amazom.com

“Homer and the Artists” by Anthony Snodgrass (1998) Amazon.com;

“Homer in Performance: Rhapsodes, Narrators, Characters” by Jonathan L. Ready, Christos C. Tsagalis (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Epic Rhapsode and His Craft: Homeric Performance in a Diachronic Perspective” by José González (2015) Amazon.com;

Who Wrote Homer's Epics

Richard Bentley, an 18th century English critic, claimed the “Odyssey” was written for women with the implication being it might have been written by a woman. To back up this assertion he pointed out that the epic's portrayal of women was realistic, while the male characters were wooden and "hopelessly wrong." The details about shipping, he said, were erroneous (a boat is once described as having rudders in both ends) and there seems to be a lot of details about things men usually don't worry about (there are passages, for example, about folding laundry carefully). The same idea was more forcefully put forward in the 19th century by Samuel Butler.

In 19th-century a popular theory argued that a single bard, long after the Trojan War, wove stories of military adventure into two integrated poems — a process that would be repeated in medieval romances. The English novelist and essayist Maurice Baring is credited with originating the quip that it wasn’t Homer who composed the "Iliad” and the “Odyssey” but another man by the same name. These day there are a number of modern scholars that believe Homer was more than one person. As evidence they point to inconsistencies in style, plot and dialect. These allegations could easily be attributed to sloppy translations and are impossible to prove.

On the allegations that there were two poets, the scholar Michael Schmidt sneers it's ''as though Shakespeare could not have written 'The Comedy of Errors' and 'Othello.' '' He said this was this was likely the case even though Homer’s diction was ''a composite of different dialect strands . . . as though a poet wrote in Scots, South African, Texan and Jamaican, all in a single poem.''

Homer, Hesiod and Early Greek Thought and Cosmology

Homer

“We see the working of these influences clearly in Homer. Though he doubtless belonged to the older race himself and used its language, it is for the courts of Achaean princes he sings, and the gods and heroes he celebrates are mostly Achaean. That is why we find so few traces of the traditional view of the world in the epic. The gods have become frankly human, and everything primitive is kept out of sight. There are, of course, vestiges of the early beliefs and practices, but they are exceptional. It has often been noted that Homer never speaks of the primitive custom of purification for homicide. The dead heroes are burned, not buried, as the kings of the older race were. Ghosts play hardly any part. In the Iliad we have, to be sure, the ghost of Patroclus, in close connection with the solitary instance of human sacrifice in Homer. There is also the Nekyia in the Eleventh Book of the Odyssey. Such things, however, are rare, and we may fairly infer that, at least in a certain society, that of the Achaean princes for whom Homer sang, the traditional view of the world was already discredited at a comparatively early date, though it naturally emerges here and there. [Source: John Burnet (1863-1928), “Early Greek Philosophy” London and Edinburgh: A. and C. Black, 1892, 3rd edition, 1920, Evansville University]

“When we come to Hesiod, we seem to be in another world. We hear stories of the gods which are not only irrational but repulsive, and these are told quite seriously. Hesiod makes the Muses say: "We know how to tell many false things that are like the truth; but we know too, when we will, to utter what is true." This means that he was conscious of the difference between the Homeric spirit and his own. The old lightheartedness is gone, and it is important to tell the truth about the gods. Hesiod knows, too, that he belongs to a later and a sadder time than Homer. In describing the Ages of the World, he inserts a fifth age between those of Bronze and Iron. That is the Age of the Heroes, the age Homer sang of. It was better than the Bronze Age which came before it, and far better than that which followed it, the Age of Iron, in which Hesiod lives. He also feels that he is singing for another class. It is to shepherds and husbandman of the older race he addresses himself, and the Achaean princes for whom Homer sang have become remote persons who give "crooked dooms." The romance and splendor of the Achaean Middle Ages meant nothing to the common people. The primitive view of the world had never really died out among them; so it was natural for their first spokesman to assume it in his poems. That is why we find in Hesiod these old savage tales, which Homer disdained.

“Yet it would be wrong to see in the Theogony a mere revival of the old superstition. Hesiod could not help being affected by the new spirit, and he became a pioneer in spite of himself. The rudiments of what grew into Ionic science and history are to be found in his poems, and he really did more than anyone to hasten that decay of the old ideas which he was seeking to arrest. The Theogony is an attempt to reduce all the stories about the gods into a single system, and system is fatal to so wayward a thing as mythology. Moreover, though the spirit in which Hesiod treats his theme is that of the older race, the gods of whom he sings are for the most part those of the Achaeans. This introduces an element of contradiction into the system from first to last. Herodotus tells us that it was Homer and Hesiod who made a theogony for the Hellenes, who gave the gods their names, and distributed among them their offices and arts, and it is perfectly true. The Olympian pantheon took the place of the older gods in men's minds, and this was quite as much the doing of Hesiod as of Homer. The ordinary man would hardly recognize his gods in the humanized figures, detached from all local associations, which poetry had substituted for the older objects of worship. Such gods were incapable of satisfying the needs of the people, and that is the secret of the religious revival we shall have to consider later.

Homer's Books

Apotheosis of Homer The “Iliad” and the “Odyssey” were the first and greatest stories in Western civilization and many of the events described in them took place in present-day Turkey. The 3200-year-old epics were the basis for Greek religion, morality and history and arguably Roman religion, morality and history too. The 5th-century-B.C. Poet Aeschylus claimed that all his plays were merely “slices from the great banquets of Homer.” Plato mentioned him 331 times in his dialogues.

It was Homer (perhaps Homer of Chios) who wrote the two classic works of literature the Iliad and the Odyssey. (Actually he likely didn't “write”; it seems more probable that he “dictated” to a man legend identifies as Palamedes.) The way of life that is described in the two epic poems comes mostly from Homer's own time although the period he describes extends backwards into Mycenaean times. There is still much uncertainty in academic circles about when the poems were written down-perhaps around 775BC – after centuries of being recited or sung. What is clear is that it would not have happened without the invention of the first true alphabet, the first writing that could be pronounced by someone who is not a speaker of that language. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

The Iliad and Odyssey were written in the same epic meter—dactylic hexameter—and use many similar formulas and are couched in the same dialect, which lead one to believe they are written by the same person or at least people who lived in the same general place. Homer's stories were written in verse, partly because verse was easier to remember. Homer used 8,500 different words in his works, compared to Hugo who used 38,000 different words and Shakespeare who used 24,000. The Old Testament has 5,800 different word; the New Testament, 4,800.

The era in which Homer is said to have lived is also the era that Greek writing first appeared and the illiterate Greeks began to read. The oldest verison of Homer is a medieval copy made in the 10th or 11th century Half of the documents written on Egyptian papyri that exist today are copies of the “Iliad” and “ Odyssey “ or commentaries about them. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Impact of Homer’s Work

Greek soldiers who fought in the famous Persian Wars could reportedly quote long passages of the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey” . Romans looked to the books for moral lessons and used them as the basis of their great literary work Virgil’s “Aeneid” . Through the ages the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey” relayed information from generation to generation about geography, navigation and shipbuilding.

Homer's books were the basis of Greek and Roman education. Not only did they define honor and moral conduct for the Greeks, they were the foundations of Western literature. Alexander the Great slept with a copy of the “Iliad” and traced his maternal ancestry back to Achilles. Latin translations of the Homeric classics helped spur the Renaissance and inspired writers like Dante and Milton to write in the Homeric style. Today it can argued that the ancient texts are the sources of the metaphors that life is a battle (the “Iliad” ) and life is a journey (the “Odyssey”).

It is impossible to overemphasize his impact on Greek society. Homer gave his countrymen an expected model of behavior, a handbook of values. Students relied on Homeric texts, orators and politicians quoted him and philosophers and philologists dissected his poems. As more than one person expressed it, "I studied Homer so that I might become a better man." Admirers included Alexander, the Great who slept with his sword and a copy of Homer by his bedside. The German archaeologist Schliemann would not have discovered (and inadvertently partially destroyed) the ancient city of Troy without the aid of Homer. His status as the greatest epic poet ever is rarely challenged. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

Aristotle Praises Homer for the Unity of His Plots

Aristotle

Aristotle (384-323 B.C.) wrote in “The Poetics”: ““Unity of plot does not, as some persons think, consist in the unity of the hero. For infinitely various are the incidents in one man's life which cannot be reduced to unity; and so, too, there are many actions of one man out of which we cannot make one action. Hence the error, as it appears, of all poets who have composed a Heracleid, a Theseid, or other poems of the kind. They imagine that as Heracles was one man, the story of Heracles must also be a unity. But Homer, as in all else he is of surpassing merit, here too- whether from art or natural genius- seems to have happily discerned the truth.

“In composing the Odyssey he did not include all the adventures of Odysseus- such as his wound on Parnassus, or his feigned madness at the mustering of the host- incidents between which there was no necessary or probable connection: but he made the Odyssey, and likewise the Iliad, to center round an action that in our sense of the word is one. As therefore, in the other imitative arts, the imitation is one when the object imitated is one, so the plot, being an imitation of an action, must imitate one action and that a whole, the structural union of the parts being such that, if any one of them is displaced or removed, the whole will be disjointed and disturbed. For a thing whose presence or absence makes no visible difference, is not an organic part of the whole.

“It is, moreover, evident from what has been said, that it is not the function of the poet to relate what has happened, but what may happen- what is possible according to the law of probability or necessity. The poet and the historian differ not by writing in verse or in prose. The work of Herodotus might be put into verse, and it would still be a species of history, with meter no less than without it. The true difference is that one relates what has happened, the other what may happen. Poetry, therefore, is a more philosophical and a higher thing than history: for poetry tends to express the universal, history the particular. By the universal I mean how a person of a certain type on occasion speak or act, according to the law of probability or necessity; and it is this universality at which poetry aims in the names she attaches to the personages.”

Singing Bards and Rhapsodes

In Homer's time, stories were generally heard or spoken rather than read or written. People who memorized stories spoke them at public performances to share the stories and entertain the people. It was in this manner that The Odyssey and stories like it could be passed onto new generations in a culture without an alphabet.In ancient Greek, Homer’s poems were recited by rhapsodes (song- stitchers) who could add their own personal and cultural touches depending on where and when the stories were told. It seems likely that some rhapsodes were better than others. Homer himself said: “So it is that the gods do not give all men gifts of grace - neither good looks nor intelligence nor eloquence.”

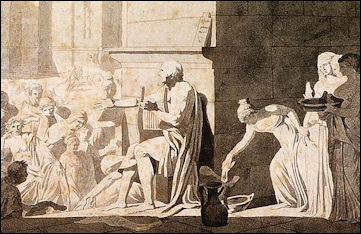

Homer Reciting his Verses

to the Greeks During Homer's time the people who told stories were mostly traveling bards who recited from memory, often accompanied by a lyre, at feasts and religious gatherings. They told stories about epic battles, heros, adventures and supernatural creatures. The "chapters" of the “Iliad “ and “ Odyssey “ came from episodes that were recited by singer-poets at social gatherings. The people listening knew the story already. Perhaps the listened to it like a pop song that gave them a lift every time they heard it.

In the early part of the 20th century a young American scholar named Milman Parry tried to get a sense of what Homer's works were originally like by observing illiterate bards in Muslim Serbia that still sang heroic epics to illiterate audiences. The bards, Parry discovered, were skilled improvisers who recounted certain episodes but told different stories every time. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

By observing the Muslim Bards, Parry determined, the chapters were perhaps an hour in length, because that was the limit of an audience's attention span, and were strung together from gathering to gathering with an involved plot and a larger theme.μ

Around the 7th century B.C., in ancient Greece, traveling bards began being replaced by trained reciters called “ rhapsode” who began using written texts and performed at poetry contests. Their tellings were thought to be less spontaneous and improvised than the singer-bards.

See Separate Article:

RHAPSODES: THE SINGING BARDS OF HOMERIC-ERA AND CLASSICAL GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Homeric Hymns

The Homeric Hymns are a collection of thirty-three anonymous ancient Greek hymns celebrating individual gods perhaps written around Homer’s time. The hymns are "Homeric" in the sense that they employ the same epic meter—dactylic hexameter—as the Iliad and Odyssey, use many similar formulas and are couched in the same dialect. They were uncritically attributed to Homer himself in antiquity—from the earliest written reference to them, Thucydides (iii.104)—and the label has stuck. "The whole collection, as a collection, is Homeric in the only useful sense that can be put upon the word;" A. W. Verrall noted in 1894, "that is to say, it has come down labeled as 'Homer' from the earliest times of Greek book-literature." [Source: Wikipedia]

Homeric Hymn XXX: To Earth the Mother of All: “I will sing of well-founded Earth, mother of all, eldest of all beings. She feeds all creatures that are in the world, all that go upon the goodly land, and all that are in the paths of the seas, and all that fly: all these are fed of her store. Through you, O queen, men are blessed in their children and blessed in their harvests, and to you it belongs to give means of life to mortal men and to take it away. Happy is the man whom you delight to honour! He has all things abundantly: his fruitful land is laden with corn, his pastures are covered with cattle, and his house is filled with good things. Such men rule orderly in their cities of fair women: great riches and wealth follow them: their sons exult with ever-fresh delight, and their daughters in flower-laden bands play and skip merrily over the soft flowers of the field. Thus is it with those whom you honour O holy goddess, bountiful spirit. 1 Hail, Mother of the gods, wife of starry Heaven; freely bestow upon me for this my song substance that cheers the heart! And now I will remember you and another song also. [Source: Hesiod, “Homeric Hymns, Epic Cycle,” Homerica. 1922]

Homeric Hymn XXXI: To Helios: And now, O Muse Calliope, daughter of Zeus, begin to sing of glowing Helios whom mild-eyed Euryphaëssa, the far-shining one, bare to the Son of Earth and starry Heaven. For Hyperion wedded glorious Euryphaëssa, his own sister, who bare him lovely children, rosy-armed Eos and rich-tressed Selene and tireless Helios who is like the deathless gods. As he rides in his chariot, he shines upon men and deathless gods, and piercingly he gazes with his eyes from his golden helmet. Bright rays beam dazzlingly from him, and his bright locks streaming from the temples of his head gracefully enclose his far-seen face: a rich, fine-spun garment glows upon his body and flutters in the wind: and stallions carry him. Then, when he has stayed his golden-yoked chariot and horses, he rests there upon the highest point of heaven, until he marvellously drives them down again through heaven to Ocean. 1 Hail to you, lord! Freely bestow on me substance that cheers the heart. And now that I have begun with you, I will celebrate the race of mortal men half-divine whose deeds the Muses have showed to mankind.

Homeric Hymn to Demeter

I begin to sing of Demeter, the holy goddess with the beautiful hair.

And her daughter [Persephone] too. The one with the delicate ankles, whom Hadês

seized. She was given away by Zeus, the loud-thunderer, the one who sees far and wide.

Demeter did not take part in this, she of the golden double-axe, she who glories in the harvest.

She [Persephone] was having a good time, along with the daughters of Okeanos, who wear their girdles slung low.

She was picking flowers: roses, crocus, and beautiful violets.

Up and down the soft meadow. Iris blossoms too she picked, and hyacinth.

And the narcissus, which was grown as a lure for the flower-faced girl

by Gaia [Earth]. All according to the plans of Zeus. She [Gaia] was doing a favor for the one who receives many guests [Hadês].

It [the narcissus] was a wondrous thing in its splendor. To look at it gives a sense of holy awe

to the immortal gods as well as mortal humans.

It has a hundred heads growing from the root up.

Its sweet fragrance spread over the wide skies up above.

And the earth below smiled back in all its radiance. So too the churning mass of the salty sea.

[Source: translated by Gregory Nagy, uh.edu/~cldue/texts/demeter]

She [Persephone] was filled with a sense of wonder, and she reached out with both hands

to take hold of the pretty plaything. And the earth, full of roads leading every which way, opened up under her.

It happened on the Plain of Nysa. There it was that the Lord who receives many guests made his lunge.

He was riding on a chariot drawn by immortal horses. The son of Kronos. The one known by many names.

He seized her against her will, put her on his golden chariot,

And drove away as she wept. She cried with a piercing voice,

calling upon her father [Zeus], the son of Kronos, the highest and the best.

But not one of the immortal ones, or of human mortals,

heard her voice. Not even the olive trees which bear their splendid harvest.

Except for the daughter of Persaios, the one who keeps in mind the vigor of nature.

Demeter

She heard it from her cave. She is Hekatê, with the splendid headband.

And the Lord Helios [Sun] heard it too, the magnificent son of Hyperion.

They heard the daughter calling upon her father, the son of Kronos.

But he, all by himself,

was seated far apart from the gods, inside a temple, the precinct of many prayers.

He was receiving beautiful sacrificial rites from mortal humans.

She was being taken, against her will, at the behest of Zeus,

by her father’s brother, the one who makes many sêmata, the one who receives many guests,

the son of Kronos, the one with many names. On the chariot drawn by immortal horses.

So long as the earth and the star-filled sky

were still within the goddess’s [Persephone’s] view, as also the fish-swarming sea [pontos], with its strong currents,

as also the rays of the sun, she still had hope that she would yet see

her dear mother and that special group, the immortal gods.

For that long a time her great noos was soothed by hope, distressed as she was.

The peaks of mountains resounded, as did the depths of the sea [pontos],

with her immortal voice. And the Lady Mother [Demeter] heard her.

And a sharp akhos seized her heart. The headband on her hair

she tore off with her own immortal hands

and threw a dark cloak over her shoulders.

She sped off like a bird, soaring over land and sea,

looking and looking. But no one was willing to tell her the truth [etêtuma],

not one of the gods, not one of the mortal humans,

not one of the birds, messengers of the truth [etêtuma].

Thereafter, for nine days did the Lady Demeter

wander all over the earth, holding torches ablaze in her hands.

Not once did she take of ambrosia and nectar, sweet to drink,

in her grief, nor did she bathe her skin in water.

But when the tenth bright dawn came upon her,

Hekatê came to her, holding a light ablaze in her hands.

She came with a message, and she spoke up, saying to her:

“Lady Demeter, bringer of hôrai, giver of splendid gifts,

which one of the gods who dwell in the sky or which one of mortal humans

seized Persephone and brought grief to your philos thûmos?

I heard the sounds, but I did not see with my eyes

who it was. So I quickly came to tell you everything, without error.”

So spoke Hekatê. But she was not answered

by the daughter [Demeter] of Rhea with the beautiful hair. Instead, she [Demeter] joined her [Hekatê] and quickly

set out with her, holding torches ablaze in her hands.

They came to Hêlios, the seeing-eye of gods and men.

They stood in front of his chariot-team, and the resplendent goddess asked this question:

Homeric Hymn to Dionysus

Dionysus procession

“I will tell of Dionysus, the son of glorious Semele, how he appeared on a jutting headland by the shore of the fruitless sea, seeming like a stripling in the first flush of manhood: his rich, dark hair was waving about him, and on his strong shoulders he wore a purple robe. Presently there came swiftly over the sparkling sea Tyrsenian1 pirates on a well-decked ship —a miserable doom led them on. When they saw him they made signs to one another and sprang out quickly, and seizing him straightway put him on board their ship exultingly; for they thought him the son of heaven-nurtured kings. They sought to bind him with rude bonds, but the bonds would not hold him, and the withes fell far away from his hands and feet: and he sat with a smile in his dark eyes. [Source: Anonymous. “The Homeric Hymns and Homerica” translated by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Homeric Hymns. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914]

Then the helmsman understood all and cried out at once to his fellows and said: “Madmen! what god is this whom you have taken and bind, strong that he is? Not even the well-built ship can carry him. Surely this is either Zeus or Apollo who has the silver bow, or Poseidon, for he looks not like mortal men but like the gods who dwell on Olympus. Come, then, let us set him free upon the dark shore at once: do not lay hands on him, lest he grow angry and stir up dangerous winds and heavy squalls.”

“So said he: but the master chid him with taunting words: “Madman, mark the wind and help hoist sail on the ship: catch all the sheets. As for this fellow we men will see to him: I reckon he is bound for Egypt or for Cyprus or to the Hyperboreans or further still. But in the end he will speak out and tell us his friends and all his wealth and his brothers, now that providence has thrown him in our way.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024