AGRICULTURE IN ANCIENT GREECE

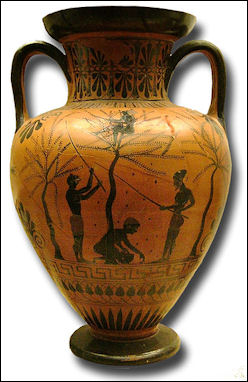

jug showing olive harvesting Cultivation of grains, olives and grapes has been practiced in what is now Greece since prehistoric times. The soil in Greece is generally poor. The Greeks grew grain at the bottom of the valleys and grapes and olives on the hill slopes. Greek-farmer soldiers usually only possessed about 15 acres of land or less. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

According to myth, Promethius was caught stealing fire from the gods and consequentially brought the harsh necessity of agricultural labour upon the Greeks. It was seen as a punishment imposed by a vengeful Zeus because without this labour seeds could not be converted into edible plants (Garnsey 1999).

One Italian archeobotanist told National Geographic that the Greeks "knew that some sites were good for olives, others for vines or wheat. So they divided the land accordingly. They brought new tools for deeper plowing. They rotated crops. They used cattle dung to fertilize fields. They knew that if you prune a tree properly, you get a much better yield."

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Greek Agriculture: An Introduction” by Signe Isager and Jens Erik Skydsgaard (1992) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Ancient Agriculture (Blackwell) by David Hollander and Timothy Howe (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Other Greeks: The Family Farm and the Agrarian Roots of Western Civilization”

by Victor Davis Hanson (1999) Amazon.com;

“Plant Foods of Greece: A Culinary Journey to the Neolithic and Bronze Ages” by Soultana Maria Valamoti (2023) Amazon.com;

“Food and Drink in Antiquity: A Sourcebook: Readings from the Graeco-Roman World” (Bloomsbury Sources in Ancient History) by John F. Donahue (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Early Neolithic in Greece: The First Farming Communities in Europe (Cambridge World Archaeology) by Catherine Perlès , Gerard Monthel (Illustrator) Amazon.com;

“Oil, Wine, and the Cultural Economy of Ancient Greece: From the Bronze Age to the Archaic Era” by Catherine E. Pratt (2021) Amazon.com;

“Estate Management and Symposium” (Oxford World's Classics) by Xenophon Amazon.com;

“Warfare and Agriculture in Classical Greece” by Victor Davis Hanson (1998) Amazon.com;

“Famine and Food Supply in the Graeco-Roman World: Responses to Risk and Crisis”

by Peter Garnsey (1988) Amazon.com;

“On Horsemanship” by Xenophon Amazon.com;

“The Culture of Animals in Antiquity” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones and Sian Lewis (2020) Amazon.com;

“Interactions between Animals and Humans in Graeco-Roman Antiquity” by Thorsten Fögen and Edmund V. Thomas (2017) Amazon.com;

Development of Agriculture

Agriculture began around 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. Considered the most important human advance after the control of fire and the creation of tools, it allowed people to settle in specific areas and freed them from hunting and gathering. According to the Bible, Cain and Abel, the sons of Adam and Eve, developed agriculture and domesticated animals, .”Now Abel was a keeper of sheep, and Cain a tiller of the ground,.” the Bible reads.

The first documented agriculture occurred 11,500 year ago in what Harvard archaeologist Ofer Ban-Yosef calls the Levantine Corridor, between Jericho in the Jordan Valley and Mureybet in the Euphrates Valley. At Mureybit, a site on the banks of the Euphrates, seeds from an uplands area — where the plants from the seeds grow naturally — were found and dated to 11,500 years ago. An abundance of seeds from plants that grew elsewhere found near human sites is offered as evidence of agriculture.

Wheat and barley agriculture spread out of Fertile crescent by 7000 B.C. By 6000 B.C., it had gotten as far as the Black Sea and present day Greece and Italy. By 5000 B.C. it had spread to most of southern Europe. The Linear Pottery Culture of central Hungary is believed to have introduced agriculture to central Europe around 5000 B.C. Agriculture finally reached southern Britain and Scandinavia around 3800 B.C. and north Britain and central Scandinavia by 2,500 B.C.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ORIGIN AND EARLY HISTORY OF AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com ;

IMPORTANT EARLY DEVELOPMENTS IN AGRICULTURE: PLOUGHING, FERTILIZER, IRRIGATION factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST GRAINS AND CROPS: BARLEY, WHEAT, MILLET, SORGHUM, RICE AND CORN factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST NON-GRAIN CROPS: NUTS, FIGS, BEANS, OLIVES, FRUIT AND POTATOES factsanddetails.com

SPREAD OF AGRICULTURE TO EUROPE europe.factsanddetails.com

Farmers in Ancient Greece

wheat During the 5th century B.C. most farmers were small landowners. A typical farmer possessed olive and fig trees, and grew some wheat and barley on their plots of land. From the third century B.C. onwards, the sudden influx of cheap slave labor and the growth of abnormally large estates in Roman Italy dispossessed many small landholders and tenant-farmers and sent them to swell the ranks of an ever-increasing urban population." Former tenant farmers were claimed as slaves.||

The prejudice against many professions was not equally directed against all. Agriculture was least liable to it. In the heroic period, agriculture was the chief occupation, not only of the lower classes, but even of the nobles and princes, who regarded it as no disgrace to perform with their own hands, or superintend, many duties connected with farming. It was natural that a change should be gradually introduced in these patriarchal conditions, and this was due not only to political revolutions, but also to the advance of civilisation, and the growth of industrial and commercial life in Greece; yet agriculture always remained one of the most respected occupations, especially in those states whose geographical position cut them off from trade, and the nature of whose soil was suited for agriculture and cattle-rearing; in these places the citizens too took part in these occupations, though in other places, especially at Sparta, any work performed with the hands was regarded as unsuitable for citizens, and was assigned to slaves or free subjects. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

In the large towns, such as Athens, where trade and industry attained a great height, and democracy, growing freer and freer, tended to advance idleness by official gifts to citizens, such as the show-money and public meals, agriculture lost in general estimation, and the citizen of a large town regarded the industrious countryman as a creature of a lower rank. This was but natural, and we find analogy for it in many of our modern conditions.

Farming in Ancient Greece

Local circumstances naturally had a good deal to do in determining the position occupied by an agricultural population. Where the land was good and the profits considerable, the farmer occupied a better position than in those places where but a poor harvest rewarded his toil. The soil of Greece was not everywhere suited for agriculture, and in many places it required the most careful labour to win any fruits from it. In Hellas, the mountainous districts are more extensive than the plains suitable for cultivation; consequently in many places they had to construct artificial terraces, because the stony ground would not otherwise have borne any fruit. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

In other places too, want of water, which in the hot season of the year often amounted to actual drought, necessitated artificial irrigation by means of canals and drainage, and again, the mountain brooks, which often overflowed their banks in the rainy season and threatened destruction to the fields, had to be regulated by means of dykes. Descriptions of such structures have come down to us, and many traces of them may still be found in Greece, some of them even pointing to very considerable technical knowledge; the State, too, sometimes undertook work of this kind, as is proved by the office of water-superintendent, who, in many places, had the control of the natural and artificial watercourses, and whose duty it was to prevent undue use, and to inflict fines in such cases.

We know very little about the management of farms and the arrangements for dividing land among large landowners or small cultivators, in the separate districts of Greece. Greek antiquity shows no traces of latifundia, such as gradually made way in Italy; there were some large estates with numerous slave-workers, but small farms were commonest. In some districts, as for instance in Arcadia, a small peasantry were the chief part of the population, and it is not surprising, therefore, that even the leaders of the State did not shrink from taking part in agricultural labour, though the larger landowners left this to their slaves and overseers. The Athenians, however, regarded the rough manners of these smaller farmers as coarse, and the citizens of the larger towns, accustomed to the refinements of ordinary life, mocked at their rustic manners; we scarcely ever find any recognition of the fact that a strong and healthy race of peasants together with an industrious middle-class is the best means for maintaining the life of a state.

Agricultural Tools in Ancient Greece

olive oil extractor juicer

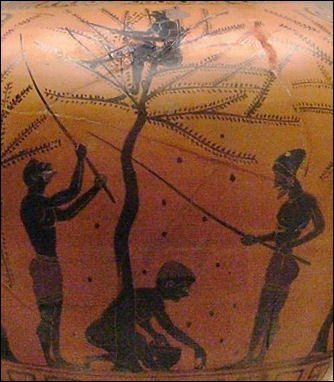

Ancient Greek agricultural tools consisted of copper, bronze or iron sickles, shears, and pick axes. Sometimes cattle were hooked up to primitive plows, but for the most part all the work was done by hand. Fields were tilled with shovels and spades and olives were beaten out of trees with sticks and collected in baskets.

A bronze farmyard group shows the animals and utensils most necessary to a farmer, and though Roman, will serve as an illustration of Greek life as well. The animals include two bulls, two cows, a pig and a sow, a ram and a ewe. There are also two double yokes, a cart, and a plough. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

The plough-tail has been lost, but a hole shows the place of attachment. The remainder is in one piece, though the joints of the rude wooden original are carefully represented, the pole which is fastened to the yoke being attached to the share-beam by pegs and the share-beam to the share by thongs or ropes. This primitive wooden plough is still used in Greece today. The cart is merely a platform with a front-board and tail-board, mounted on solid wheels. A terracotta cart from Cyprus, though of the early Iron Age, is much like the Roman cart. A small bronze sickle with indented edge from Cyprus belongs to a type common in Minoan Crete.

Farming Practices in Ancient Greece

In Homer, we find the custom, which always prevailed afterwards, of alternating only between harvest and fallow; even the succeeding ages seem to have known nothing of the rotation of crops. The implements used for the necessary farming occupations were of the simplest kind, in particular the primitive plough, which was not sufficient to tear up the earth, so that they had to use the mattock in addition; they had no harrow or scythe, in place of which they used the sickle, and their threshing arrangements were most unsatisfactory, since they simply drove oxen, horses, or mules over the threshing floor, and beat out the ears with their hoofs, by which means a great part of the harvest was lost.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

It was only the large number of labourers at the disposal of the farmers, in consequence of the numerous slaves, to which at times, when there was a press of work, they added hired labourers, and the great care taken in manuring and improving the ground, etc., that enabled them to earn a living at all. Great wealth was never attained in ancient Greece by agriculture, certainly not by growing corn; vines and olives supplied better profits, though here too the instruments used were of the simplest, but the ground was especially favorable to their cultivation. Oil, in particular, could be supplied by Greece to foreign countries, but corn did not grow in a quantity sufficient to provide their own population, and consequently they had to import a great deal from foreign countries, especially from the Black Sea, and afterwards too from Egypt.

Greek writers give us very little information about the life of the country people; a few simple pictures taken from vase paintings afford some little notion of it. One image represents three countrymen surrounded by a variety of animals: deer, lizards, a tortoise, a strange bird, and another creature, perhaps meant to represent a locust; each of the men is directing a plough drawn by two oxen, holding the handle in one hand, and in the other the goad-stick for urging on the beasts. Behind one of the ploughmen walks a man with a large basket on his left arm, in which, no doubt, there are supposed to be seeds, which he is about to strew with his right hand. Another image represents a scene from the olive harvest. On the right and left of an olive tree sit two men, before them on the ground stand jars; one of them holds a little flask in his left hand, and appears to be squeezing the juice of an olive into it through a funnel, in order to test the quality of the harvest. The inscription on the picture is, “O, Father Zeus, would that I might grow rich!” The reverse side of the vessel, not represented here, shows the fulfilment of this simple prayer in the picture and inscription.

Olive Oil Production and Olive Tree Cultivation

Olive oil and olives were widely used and consumed in ancient Greece. Olive oil is labor-intensive and time-consuming to make. Most oils are made using a simple press. Tom Mueller wrote in the New Yorker, “they are more like fresh-squeezed orange juice than industrial fats. Oil is usually dark green after it is us pressed and turns a golden color over time as it ages and settles.

Greek olive gathering Olive oil is made from olives that are picked by hand from November to January, then washed in cold water and crushed pit and all into a gooey paste under granite wheels. The paste is spread over bags or mats made from rush, grass or hemp. These mats are the stacked in piles and pressed, producing the oil. It takes about five kilograms of olives to produce one liter of oil. The oil is then placed into vats. In the old days the presses were powered by donkeys, camels, cattle and mules and later steam. Today they are mainly driven by electricity. In Tunisia olive oil is still made from camel-driven presses.

Gnarled olive trees survive well in places with dry climates, particularly in the Mediterranean Some olive trees take 15 years to bear fruit. There is old saying that farmers would grow a vineyard for their sons and an olive tree grove for their grandsons. But once they start producing, they can keep producing for centuries. These day varieties of olive of tree are available that begin producing fruit after tree or four years.

Olives need sandy soil and at least 180 mm of rain fall. They are pruned and fertilized. The olive fly is the the primary olive pest. Olives are vulnerable to killing frosts — an ice storm in January 1985 killed hundred of thousands of olive trees One farmer in Tuscany lost all but 79 of his 2,800 trees — but overall are incredible survivors. Even if the central trunk is eaten away by disease, the tree manages to survive.

See Separate Article: OLIVES: OIL, HISTORY, PRODUCTION AND SCAMS factsanddetails.com

Grape Production in Ancient Greece

The cultivation of the vine and wine-making for domestic use were a part of the yearly routine on the farms of Greece and Italy, while the finer kinds of wine were a valuable article of commerce. One object that illustrates wine-making is an Arretine bowl decorated with figures of satyrs gathering and treading grapes. The process of getting rural produce to market is represented by two terracotta figures of donkeys with panniers whose counterparts can be seen in Greece at the present day. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Between 3000 and 2700 B.C. the Egyptians were marketing wines in amphorae with labels that indicated the year, the contents, where it was produced, the owner of the vineyard and the quality with the best being rated as “very, very good.” . Between 3000 and 2500 B.C. winemaking became a major export business in what is now Shiraz in Iran. The Sumerians and other Mesopotamian groups were major buyers. Viticulture arrived in Crete in 2500 B.C. From there it made its way to Greece. A Greek drinking cup from the 6th century B.C. shows the god Dionysus carrying grapes in a ship across the Mediterranean.

The Greeks and Romans loved wine so much they created the gods Dionysus and Bacchus to honor it. The Greeks drank wine mixed water at a ratio of about three parts water to one part wine. Historians believe that wine was introduced to France (Gaul) by the Romans. Roman wine was generally thick syrupy stuff stored in amphorae and mixed with water — at a ratio of two to one or three to one — before it was consumed. In Roman times the best French wine came from Béziers. The native drink of Gaul was cervoise, a beer-like drink made from grain.

See Separate Articles: WINE, DRINKING AND ALCOHOLIC DRINKS IN ANCIENT GREECE factsanddetails.com ; WINE BASICS, AND HOW WINE IS MADE factsanddetails.com; EARLIEST WINES, WINEMAKING, WINERIES AND WINE GRAPES factsanddetails.com

Domesticated Animals and Pets in Ancient Greece

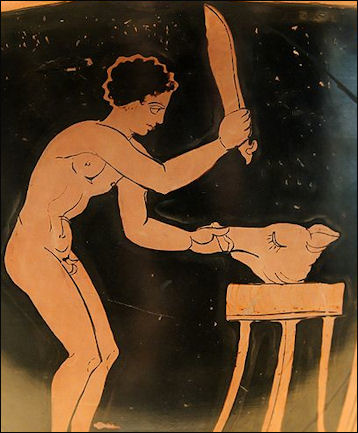

5th century BC Greek pig figurine The main domesticated animals possessed by the Greeks and used for overland transportation were including horses, mules, donkeys and oxen. Pigs were raised for food and sacrifices. According to Encyclopedia.com: Of these animals, donkeys and mules were the most versatile and commonly used. They were either ridden, hitched to wheeled vehicles, or used as pack animals capable of carrying three or four times as much cargo as a human. Oxen were useful as draft animals when large loads had to be transported. They had greater pulling power and could be harnessed more efficiently than either horses or mules. The drawbacks to oxen were that they were slow (averaging about one mile per hour versus three miles per hour for mules), and they were also rare and expensive compared to donkeys and mules.

Horses were in frequently employed because they were expensive to obtain and raise; they were a privilege indulged in by the upper classes and used chiefly for racing and, to a lesser extent, warfare. Although far more fleet of foot than donkeys or mules, horses were difficult to control, more temperamental, less surefooted on mountain roads and tracks, and prone to injury.

Monkeys and dogs were kept as pets, and a few lucky children even got to have pet cheetahs. Representations of pet animals from ancient Greece include an old gentleman walking with his sharp-nosed Melitean dog on interior of the kylix by Hegesiboulos. Cocks and quails were kept for fighting by boys and young men. Ganymede on an amphora carries his cock on his arm. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT GREEK TRANSPORTATION: MULES, OXEN, CARTS AND FOOT TRAVEL europe.factsanddetails.com

PETS IN ANCIENT GREECE: DOGS, GEESE, CHEETAHS AND CATS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK SACRIFICES europe.factsanddetails.com

EARLY DOMESTICATED ANIMALS factsanddetails.com ;

PIGS: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, PRODUCERS AND PORK-EATING CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com ;

DONKEYS, MULES AND ONAGERS: THEIR HISTORY, USES AND BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

Livestock in Ancient Greece

Domesticated animals raised on ancient Greece include horses, asses, mules, and oxen, and also sheep, goats, and pigs. Large horses first appeared in Greek times. Greeks developed the first horseshoes in the A.D. forth century. Sheep were raised for their fine wool. Bronze shepherd’s crooks found in ancient Greek sites recall the important place held by the care of sheep and goats in ancient country life. A stone model of a sheep-fold in the Cesnola Collection, containing sheep and a drinking-trough, was intended as a votive offering, probably for increase of flocks. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

pig sacrifice A Hungarian biologist told National Geographic that the Greeks were often cruel to their animals. "They were quite rude to them," he said. "I've found cattle with unhealed fractures. Their owners could have set the bones easily, but they didn't bother. Animals were often beaten. I've seen many fractures on the heads of dogs."

Except in a few districts, horse-rearing was of little importance. The mountainous nature of the country made the use of horses for driving difficult, nor do they seem to have been required for carrying burdens; they were chiefly used for riding purposes, for the cavalry, and also for travelling, racing, etc.; and in connection with racing horse-rearing became a favorite occupation of the aristocracy, and almost a mania at Athens at the time of the Peloponnesian war, when many young men were ruined by it. Horse-rearing was best developed in Thessaly, where the wide plains were suitable for the purpose. The Thessalian cavalry was always noted for its quantity and excellence. For domestic use mules and asses took the place of horses, especially as beasts of burden. The mules were used for drawing and for the plough, while the asses were chiefly employed for carrying burdens. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Pig-rearing, on the other hand, played a very small part, for it was not sufficiently remunerative. Although the flesh was used for food, yet, in the historic period it was not so popular a dish as in the age of Homer, and they did not understand how to draw a profit in other ways from pigs.

Chickens were raised in Egypt and China for meat and eggs by 1400 B.C. Greeks ate them and they were in Britain at the time the Romans arrived. They were brought to New World by explorers and conquistadors. Chickens and other fowl were known to the Greeks. The expression "Don't count your chickens before they are hatched" is attributed to Aesop in 570 B.C. In the story “ The Milkmaid and her Pail” , Patty the farmer's daughter says, "The milk in this pail will provide me with cream, which I will make into butter, which I will sell at the market, and buy a dozen eggs, and soon I shall have a large poultry yard. I'll sell some of the fowls and buy myself a handsome new gown."

Sheep and Goats in Ancient Greece

Sheep-rearing, however, was very general, and brought to great perfection, since they not only used the flesh and milk of the sheep for food, but in particular required their skin and wool for clothing. Linen was not much worn; the country people wore sheepskins, and the rest of their dress was almost entirely made of sheep’s wool. Excellent qualities of this were produced by Hellas proper, as well as by the Greek colonies in Asia Minor and Lower Italy, and a great deal of it was exported to foreign countries, where the woollen stuffs of Asia Minor, Attica, and Megara, were held in great repute from most ancient times. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The sheep got most attention, because the excellence of the wool depended on the care they received, and Diogenes is supposed to have said that it was better at Megara to be a ram than the son of a citizen, for the sheep were carefully covered up, but the children were allowed to run about naked. This custom of covering the sheep with skins to preserve the wool existed in other places too. As Greece was not rich in pasture land, there was a difficulty occasionally in providing sufficient pasture for the herds; sometimes they had to be sent to very distant parts, it even happened that states made treaties together, which permitted the citizens of one state to use the pasture land of another for a fixed period.

Goats were chiefly kept for the sake of the milk; the skins were used by the peasants for clothing. The goat’s hair was woven into stuff, not in Greece itself, but probably in Northern Africa and Cilicia, where a kind of coarse cloth was manufactured of it, which however was not often used for clothing. The facility of goat-rearing, which required no special care, and could be carried on even on rocky ground, where but little grass grew, enabled it to become very extensive, and we find it, in fact, throughout almost the whole of Greece in ancient times.

RELATED ARTICLES:

GOATS: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, MILK AND MEAT factsanddetails.com ;

SHEEP: THEIR HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS AND DOLLY factsanddetails.com

WOOL: HISTORY, TYPES, PROCESSING AND TRADE factsanddetails.com

Cattle in Ancient Greece

Ophiotaurus Mosaic; In Greek mythology, the Ophiotaurus was a creature that was part bull and part snake

Cattle-rearing played a very important part in Greek farming. In the time of Homer it even exceeded agriculture in importance; the wealth of great people at that time consisted chiefly in herds; to give cattle as a bridal gift was very common; in calculations of value cattle formed the basis instead of coined money, which was at that time unknown.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Cattle-rearing seems to have been more important in the Homeric age than afterwards, when the needs of the population could not be satisfied by the home growth, and importation of foreign cattle from the Black Sea and from Africa was necessary. The small number of herds of cattle was probably due to the fact that in Greek antiquity very little cow’s milk was drunk, but chiefly goat’s milk.

Cattle-rearing was conducted on tolerably rational principles. They were very careful in the choice of the animals used for breeding, and in very early times attempts were made to improve the race by importing foreign kinds from other countries. The cattle were chiefly fed on pasture; the herds were driven out not only in summer, but even in winter, when the climate permitted it; and in summer they were taken to the mountains and forests, in winter to the plains.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FIRST CATTLE AND COW DOMESTICATION factsanddetails.com ;

CATTLE: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND MEAT factsanddetails.com

First Chickens in the West

Some of the earliest evidence of chickens being consumed as food in the West comes from Maresha, an ancient, abandoned city in Israel that flourished in the Hellenistic period from 400 to 200 B.C.. “The site is located on a trade route between Jerusalem and Egypt,” says Lee Perry-Gal, a doctoral student in the department of archaeology at the University of Haifa. As a result, it was a meeting place of cultures, “like New York City,” she says. [Source: Daniel Charles, NPR, July 20, 2015]

Daniel Charles of NPR wrote: “The surprising thing was not that chickens lived here. There’s evidence that humans have kept chickens around for thousands of years, starting in Southeast Asia and China. But those older sites contained just a few scattered chicken bones. People were raising those chickens for cockfighting, or for special ceremonies. The birds apparently weren’t considered much of a food.

In Maresha, though, something changed. The site contained more than a thousand chicken bones. “They were very, very well-preserved,” says Perry-Gal, whose findings appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Perry-Gal could see knife marks on them from butchering. There were twice as many bones from female birds as male. These chickens apparently were being raised for their meat, not for cockfighting.

See Separate Article: CHICKENS: THEIR HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS AND DOMESTICATION europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024