ECONOMY OF ANCIENT GREECE

Female baker The earliest traders of the Mediterranean lands practiced barter, and in the Homeric poems we find cattle and bronze utensils frequently mentioned as standards of value. In the later part of the eighth century or the early part of the seventh century B.C., coinage originated in Asia Minor and made it way to Greece a few decades later.

After the Persian Wars, the city-states of Greece produced a government and culture organized and wealthy enough to allow the development of a private citizenship and with this a fledgling capitalist society. Wealth became separated from state ownership allowing individuals, some of whom became powerful oligarchs, to accumulate property and assets. Many loans were recorded on documents from the classical age but few of them were banks. The annual interest rate typically was around 12 percent. [Source: Wikipedia]

The ancient Greeks city of Aphrodisias boasted three supermarkets with set prices. To keep the economy stable sometimes the currency was devalued and wage and price controls were implemented. Yet, the French historian Fernand Braudel "observed that the Alexandrians had enough technical knowledge to start an industrial revolution but lacked the economic incentive to create labor-saving machinery because they relied on slaves."

Grain (wheat, oats and barely), olives, grapes, olive oil and wine were commonly traded goods. They were stored and transported by ships in large jug-like clay amphoras. Merchants in the Italian colonies grew wealthy by exporting wheat, oats and barley to Greece in return for pottery and bronze figurines. The Greeks had schools for mirror making, where students were taught the finer points of sand polishing.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

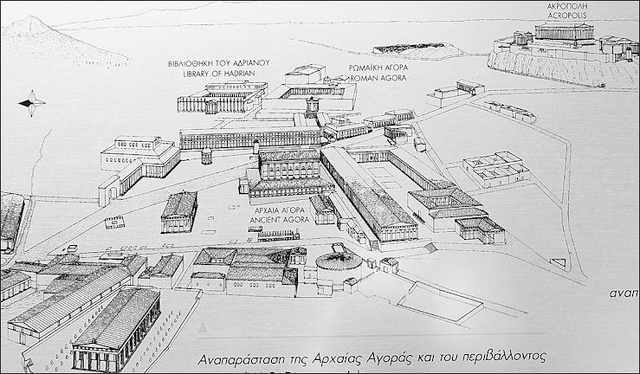

Most Greek cities and towns were organized around an agora (known to Romans as a forum), which served as a market area and meeting place Bronze workers, marble craftsmen, makers or terra cotta figurines and farmers all sold their products in the agora. Grecian Flower Market by John William Waterhouse Nearly every city of ancient Greece had an agora by about 600 B.C., when Greek civilization began to flourish. Heather Whipps wrote in Live Science: “Not only did the ancient Greeks go to the agora to pick up fresh meat and some wool for a new robe, but also to meet and greet with friends and colleagues.... Usually located near the center of town, the agora was easily accessible to every citizen, with a large central square for market stalls bound by public buildings. [Source: Heather Whipps, Live Science, March 16, 2008] “Who knows where we'd be without the "agoras" of ancient Greece. Lacking the concept of democracy, perhaps, or the formula for the length of the sides of a triangle (young math students, rejoice!). Modern doctors might not have anything to mutter as an oath. What went on at the agora went beyond the simple daily transactions of the market. The conversations that happened there and the ideas that they bore continue to affect us to this day, from the way scientists carry out their work to how we pass our laws. “The agora of Athens – the hub of ancient Greek civilization – was the size of several football fields and saw heavy traffic every single day of the week. Women didn't often frequent the agora, but every other character in ancient Greece passed through its columns: politicians, criminals, philosophers and traders, aristocrats, scientists, officials and slaves.” The ancient agora (market) of Athens was located just below the Parthenon on the north side of the Acropolis. It was where people shopped, voted, socialized and discussed the issues of the day. The comic poet Eubulus wrote: "You will find everything sold together in the same place at Athens: figs, witnesses to summons, bunches of grapes, turnips, pears, apples, givers of evidence, roses, meddlers, porridge, honeycombs, chickpeas, lawsuits, bee-sting-puddings, myrtle, allotment machines, irises, lambs, water clocks, laws, indictments." Agora of Athens Located between ancient Athen's main gates and the Acropolis, it was filled with workshops, markets, and law courts and was huge area, covering about 30 acres. On work days, vendors set up shop in wicker stalls. There were areas for moneychangers, fishmongers, perfumeries, and slave traders. Visitors today still find hobnails and bone eyelets in an ancient cobbler' shop.

Laid out today like a park, and littered with thousands of pieces of columns and building, the Agora was ancient Athens' administrative center and main marketplace and gathering place. Socrates likes to hang out the agora in Athens. Xenophon wrote that his former teacher "was always on public view; from early in the morning he used to go to the walkways and gymnasia, to appear in the agora as it filled up, and to be present wherever he would meet with the most people." Socrates used to address his followers in the Agora. While on trial for insulting the gods, he was kept in the prison annex outside the angora. Plato, Pericles, Thucydides and Aristophenes all spent a lot of time in the agora. Citizens who avoided military service, showed cowardice in battle and mistreated their parents were forbidden from entering the Angora. Heather Whipps wrote in Live Science: Athens’ agora “was the heart of the city – where ordinary citizens bought and sold goods, politics were discussed and ideas were passed among great minds like Aristotle and Plato. Some of the world's most important ideas were born and perfected within the confines of the Athenian agora including, famously, the concept of democracy. [Source: Heather Whipps, Live Science, March 16, 2008 ] “The Athenian democratic process, whereby issues were discussed in a forum and then voted on, is the basis for most modern systems of governance. Regular Athenian citizens had the power to vote for anything and everything, and were fiercely proud of their democratic ways. No citizen was above the law – laws were posted in the agora for all to see – or was exempt from being a part of the legal process. In fact, Athenians considered it a duty and a privilege to serve on juries. Both the city law courts and senate were located in the agora to demonstrate the open, egalitarian nature of Athenian life. “Scientific theory also got its start in the agora, where the city's greatest minds regularly met informally to socialize. Socrates, Plato and Aristotle all frequented the Athenian agora, discussed philosophy and instructed pupils there. Aristotle, in particular, is known for his contributions to science, and may have developed his important theories on the empirical method, zoology and physics, among others, while chatting in the agora's food stalls or sitting by its fountains. Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine and its Hippocratic Oath, and Pythagoras, a mathematician who developed the geometric theory of a triangle's sides, were both highly public figures who taught and shared ideas in their own hometown agoras.” Around the agora were courts, assembly halls, military headquarters, the mint, keepers of weights and measurements, commercial buildings, a racetrack and shrines. On a hill behind the agora are the remains of the columned halls of the Hephaisteion (449 B.C, a temple dedicated to Hephaisteion), the best preserved Doric Temple in Greece. It contains friezes of Theseus battling the Minotaur, the labors of Hercules and the battle of the Centaurs. Below the Hephaisteion is the New Bouleuterion, where the 500-member Boule (Senate) met. Nearby is the Tholos, where the 50 members of the executive committee of the Boule met. In front of the Bouleuterion there were statues of the Eponymous Heroes (ten tribal namesakes chosen by the oracle of Delphi). This was a popular gathering spot. Other building in and around the Agora included the Shop of Simon the Cobbler, the Stoa of Zeus (a covered colonnade and religious shrine for Zeus), the Royal Stoa, the Painted Stoa (contained beautiful wall paintings that were taken by the Romans and have since been lost), the Altar of the Twelve Gods, the Panathanaic Way (a diagonal street running uphill to the Acropolis and parade route during major festivals), Mints, Fountain House, South Stoa and a, Racetrack. Stoa of Attalus (159-138 B.C.) is completely restored two story building in the Agora, with internal and external rows of columns, that was formerly an arcade with 21 shops. The museum inside the Stoa Attalus contains a slotted marble slab with numbered balls used to select assembly members, a water clock that ensured that speeches did no exceed six minutes, thimble-size terra cotta vessels used by executioners to measure doses of hemlock, pottery shards that were used for secret votes to ostracize people (a 10 year banishment), part of an old ballot box used for the election of city officials and a bronze shield taken from the defeated Spartans. Athenian citizen used to line the promenade of the Stoa of Attalos in the Agora to watch the Panatheenaic procession in which a huge dress was hauled up to the Acropolis as an offering to Athena. Near the Parthenon was a 30-foot-high bronze statue of Athena Promachos, the Warrior, whose metal glistened so brightly it was said it could be seen by ships approaching Athens. Argilos In the summer of 2013, archaeologists uncovered a 2,500-year-old portico — a bustling public space likened to ancient strip mall — in the ancient city of Argilos, situated on the scenic northern coast of the Aegean Sea in present-day Greece. At the time five of the seven storerooms that make up the portico had been excavated. Megan Gannon wrote in Live Science: “The seaside portico, or stoa, stretches 130 feet (40 meters) across with seven rooms inside, each bearing the distinct architectural touches of their ancient shop owners, the site's excavators say. Strewn about the ruins, archaeologists found coins, vases and other artifacts that hold clues to when and how people lived in the archaic city. “Porticos are well known from the Hellenistic period, from the third to first century B.C., but earlier examples are extremely rare," archaeologist Jacques Perreault, a classicist at the University of Montreal, said in a statement. "The one from Argilos is the oldest example to date from northern Greece and is truly unique." [Source: Megan Gannon, Live Science, October 10, 2013] “Perreault is a co-director of the dig at Argilos, which was strategically located just west of the Struma River, an area dotted with ancient gold and silver mines. Researchers think the city was founded around 655 B.C., making it perhaps the earliest Greek colony on the Thracian coast.

Argilos hit its stride in the fifth century B.C., but went into decline shortly after, when the nearby city Amphipolis was founded as an Athenian outpost. In 357 B.C., Philip II of Macedon conquered the region and deported the residents of Argilos to Amphipolis. Archaeologists at the site think Argilos was largely deserted after its fourth-century inhabitants were forced to leave; excavations have not turned up any Roman or Byzantine ruins from later periods, according to the dig's website. The remains of the portico were discovered during this past summer's field season, at the edge of the city's former commercial district, about 160 feet (50 m) from the ancient port, the researchers say. The archaeologists partially dug up five of the portico's storerooms, finding curious differences in each space that suggest the building was not a city-sponsored project with one architect in charge. The construction techniques and the stones used are different for one room to another, hinting that several masons were used for each room," Perreault explained in a statement. "This indicates that the shop owners themselves were probably responsible for building the rooms, that 'private enterprise' and not the city was the source of this stoa."” In the eyes of the Greeks, tradesmen stood on the same footing as mechanical labourers. There was, of course, a distinction; if the cultured Greek, who occupied himself only with higher intellectual pursuits, despised the artisan because he regarded his bodily activity as unworthy of a free man, the tradesman seemed to him contemptible because he was influenced only by desire for gain, and all his striving was to get the advantage over others.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895] The profit and wealth accruing to so many Greek states from trade was not sufficient to decrease the prejudice against money-making occupations, even the common people were not able to understand that the merchant, on account of the risk of injury, or even loss of his goods, changing conditions of price, and all his own trouble involved, was obliged to demand a higher price for his wares than what had been originally paid by himself; and the opinion that the merchant’s business was based on love of gain and deceit was so common that even a philosophical intellect like Aristotle’s was under the influence of this prejudice. It is possible that the Greek merchants often deserved the reputation of dishonesty which they bore; their predecessors, the Phoenicians, who had formerly carried on the whole trade of Greece, had not unduly been reproached with deceit and even robbery and piracy, and it is possible that there were traces of this still visible in the Greek merchants. Contempt for the merchant class was not equally directed at all; the wholesale dealer who imported his wares from a distance, and had little personal contact with the public, was less affected by it; in trading cities, such as Aegina and Athens, a great number of the rich citizens belonged to this class. But the small trader was the more exposed to the reproach of false weights and measures, adulteration of goods, especially food, and all manner of deceitful tricks. Some complaints were made that are still heard at the present day, that the wine dealers mixed water with their wine, that the cloth-workers used artificial dressing to make their materials look thicker, that the poulterers blew out the birds to make them seem fatter, etc. Worst of all was the reputation of the corn dealers. The division between wholesale and retail traders seems to have been somewhat sharper in Greek antiquity than at the present day, partly because the former were not only merchants but also seafarers. Cristian Violatti wrote in Listverse: The pursuit of material wealth and mostly any other activity outside of a military career was discouraged by Spartan law. Iron was the only metal allowed for coinage; gold and silver were forbidden. According to Plutarch (“Life of Lycurgus”: 9), Spartans had their coins made of iron. Therefore, a small value required a great weight and volume of coins.Transporting a significant amount of value in coins required the use of a team of oxen, and storing it needed a large room. This made bribery and stealing difficult in Sparta. Wealth was not easy to enjoy and almost impossible to hide. [Source by Cristian Violatti, Listverse, August 3, 2016] Spartans were absolutely debarred by law from trade or manufacture, which consequently rested in the hands of the perioeci (q.v.), and were forbidden to possess either gold or silver, the currency consisting of bars of iron: but there can be no doubt that this prohibitian was evaded in various ways. Wealth was, in theory at least, derived entirely from landed property, and consisted in the annual return made by the helots (q.v.) who cultivated the plots of ground allotted to the Spartans. But this attempt to equalize property proved a failure: from early times there were marked differences of wealth within the state, and these became even more serious after the law of epitadeus, passed at some time after the Peloponnesian War, removed the legal prohibition of the gift or bequest of land. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, 1911 Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University] “Later we find the soil coming more and more into the possession of large landholders, and by the middle of the 3rd century B.C. nearly two fifths of Laconia belonged to women. Hand in hand with this process went a serious diminution in the number of full citizens, who had numbered 8000 at the beginning of the 5th century, but had sunk by Aristotle's day to less than 1000, and had further decreased to 700 at the accession of Agis IV. in 244 B.C. The Spartans did. what they could to remedy this by law: certain penalties were imposed upon those who remained unmarried or who married too late in life. But the~decay was too deep-rooted to be eradicated by such means, and we shall see that at a late period in Sparta's history an attempt was made without success to deal with the evil by much more drastic measures.” See Separate Article: SPARTAN STATE AND GOVERNMENT europe.factsanddetails.com Coins were the primary means of exchange (paper money was first used by the Mongols and the Chinese around A.D.1000). Coins were usually made by striking the smooth gold and silver blanks between engraved dies of bronze or hardened iron. The die for one side usually contained the face of a ruler. The other die was for the back of the coin. Molds were only rarely used. Talents and drachmas were the names of the ancient Greek currency. One talent equaled 6000 drachmas. By one estimate a drachma was worth about $2.00 in present-day money. By another estimate it was worth about half a cent. The cost of sending a letter was around 2 talents and 300 drachmas. In most reckonings talents were a lot of money. A single talent could pay a month’s wages for a 170 oarsmen on a Greek warship. The cost of the Parthenon in Athens was estimated to worth 340 to 800 silver talents. In addition to being legal tender, coins were also regarded as works of art and forums for political views. Every city state struck its own coins, usually from silver, and their designs changed constantly to commemorate victories or rulers. The figures on these coins conveyed emotion, sereneness and strength and some their makers considered them be such works of art the coins were signed. See Separate Article: MONEY IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com Aristotle wrote in “Politics” Book I; Chapter V: “Property is a part of the household, and the art of acquiring property is a part of the art of managing the household; for no man can live well, or indeed live at all, unless he be provided with necessaries. And as in the arts which have a definite sphere the workers must have their own proper instruments for the accomplishment of their work, so it is in the management of a household. [Source: Aristotle, “The Politics of Aristotle,” translated by Benjamin Jowett,(New York: Colonial Press, 1900), pp. 4-9] “Now instruments are of various sorts; some are living, others lifeless; in the rudder, the pilot of a ship has a lifeless, in the look-out man, a living instrument; for in the arts the servant is a kind of instrument. Thus, too, a possession is an instrument for maintaining life. And so, in the arrangement of the family, a slave is a living possession, and property a number of such instruments; and the servant is himself an instrument which takes precedence of all other instruments. “For if every instrument could accomplish its own work, obeying or anticipating the will of others, like the statues of Daedalus, or the tripods of Hephaestus, which, says the poet, of their own accord entered the assembly of the Gods; if, in like manner, the shuttle would weave and the plectrum touch the lyre without a hand to guide them, chief workmen would not want servants, nor masters slaves.” Alexander silver Babylon victory coin from 322 BC The Law Code of Gortyn (450 B.C.) is the most complete surviving Greek Law code. According to the Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: “In Greek tradition, Crete was an early home of law. In the 19th Century, a law code from Gortyn on Crete was discovered, dealing fully with family relations and inheritance; less fully with tools, slightly with property outside of the household relations; slightly too, with contracts; but it contains no criminal law or procedure. This (still visible) inscription is the largest document of Greek law in existence (see above for its chance survival), but from other fragments we may infer that this inscription formed but a small fraction of a great code.” [Source:Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University] “V. If a man die, leaving children, if his wife wish, she may marry, taking her own property and whatever her husband may have given her, according to what is written, in the presence of three witnesses of age and free. But if she carry away anything belonging to her children she shall be answerable. And if he leaves her childless, she shall have her own property and whatever she has woven, the half, and of the produce on hand in possession of the heirs, a portion, and whatever her husband has given her as is written. If a wife shall die childless, the husband shall return to her heirs her property, and whatever she has woven the half, and of the produce, if it be from her own property, the half. If a female serf be separated from a male serf while alive or in case of his death, she shall have her own property, but if she carry away anything else she shall be answerable. “VII. The father shall have power over his children and the division of the property, and the mother over her property. As long as they live, it shall not be necessary to make a division. But if a father die, the houses in the city and whatever there is in the houses in which a serf residing in the country does not live, and the sheep and the larger animals which do not belong to the serf, shall belong to the sons; but all the rest of the property shall be divided fairly, and the sons, howsoever many there be, shall receive two parts each, and the daughters one part each. The mother's property also shall be divided, in case she dies, as is written for the father's. And if there should be no property but a house, the daughters shall receive their share as is written. And if a father while living may wish to give to his married daughter, let him give according to what is written, but not more. . . “X. As long as a father lives, no one shall purchase any of his property from a son, or take it on mortgage; but whatever the son himself may have acquired or inherited, he may sell if he will; nor shall the father sell or pledge the property of his children, whatever they have themselves acquired or succeeded to, nor the husband that of his wife, nor the son that of the mother. . . If a mother die leaving children, the father shall be trustee of the mother's property, but he shall not sell or mortgage unless the children assent, being of age; and if anyone shall otherwise purchase or take on pledge the property, it shall still belong to the children; and to the purchaser or pledgor the seller or pledgee shall pay two-fold the value in damages. But if he wed another, the children shall have control of the mother's property. “XIV. The heiress shall marry the brother of the father, the eldest of those living; and if there be more heiresses and brothers of the father, they shall marry the eldest in succession. . . But if he do not wish to marry the heiress, the relatives of the heiress shall charge him and the judge shall order him to marry her within two months; and if he do not marry, she shall marry the next eldest. If she do not wish to marry, the heiress shall have the house and whatever is in the house, but sharing the half of the remainder, she may marry another of her tribe, and the other half shall go to the eldest. . . “XVI. A son may give to a mother or a husband to a wife 100 staters or less, but not more; if he should give more, the relatives shall have the property. If anyone owing money, or under obligation for damages, or during the progress of a suit, should give away anything, unless the rest of his property be equal to the obligation, the gift shall be null and void. One shall not buy a man while mortgaged until the mortgagor release him. . Cleopatra coin According to AncientPages.com: “During the whole Graeco-Roman period (332 B.C. – 642 A.D.), banks were of three types, either privately run, leased, or owned by government, of which included within this last group were some organizations having dual roles including being additionally treasury departments. [Source: AncientPages.com, March 7, 2016] “In ancient Greece, private entrepreneurs, as well as temples and public bodies, undertook financial transactions. They took deposits, made loans, changed money from one currency to another and tested coins for weight and purity. They even engaged in book transactions. Money lenders can accepted payment in one Greek city and arranged for credit in another, avoiding the need for the customer to transport or transfer large numbers of coins. Ancient Rome adopted the banking practices of Greece.” Trapezitica is the first source documenting banking. According to one source (Dandamaev et al), trapezites were the first to trade using money, during the 5th century B.C, as opposed to earlier trade which occurred using forms of pre-money. The speeches of Demosthenes contain numerous references to the issuing of credit. Xenophon is credited to have made the first suggestion of the creation of an organisation known in the modern definition as a joint-stock bank in “On Revenues” written circa 353 B.C. [Source: Wikipedia +] The temple of Artemis at Ephesus was the largest depository of Asia. A pot-hoard dated to 600 B.C. was found there. During the time of the first Mithridatic war the entire debt record at the time being held was annulled by the council. The temple to Apollo in Didyma was constructed sometime in the 6th century B.C.. A large sum of gold was deposited within the treasury at the time by king Croesus. Before its destruction by Persians during the 480 B.C. invasion of Athens, the Athenian Acropolis stored money. Pericles rebuilt a depository afterward within the Parthenon and controversially took money from it pay for the Peloponnesian War. Mark Anthony is recorded to have stolen from the deposits of the temple of Artemis at Ephesus on an occasion. This temple served as a depository for Aristotle, Caesar, Dio Chrysostomus, Plautus, Plutarch, Strabo and Xenophon. + Occupations connected with money were largely developed in antiquity. The merchants who dealt with such business — the bankers and money-changers — were called by the Greeks “table-merchants”, from the table at which they originally carried on their occupations. Their duties were of a double nature; besides the actual business of changing, they undertook the investment of capital and the transaction of money business. When the increased coinage of money and the augmentation of trade and travel brought large sums into the hands of individuals, those who had not invested their possessions in wares or property or slaves, naturally desired to profit by it in some other way, and thus the loan business was gradually developed, in which capitalists lent money to those who required it for any mercantile undertaking, in return for a security and interest. In the bond executed in the presence of witnesses, the amount of the capital, the interest agreed upon, as well as the time for which the loan was arranged, had to be entered. For greater safety, a third person usually became security for the debtor, or else some possession was mortgaged, the value of which corresponded to the sum lent. They distinguished between pledges in movable objects, such as cattle, furniture, slaves, etc.; and mortgages given partly on movable objects, such as factory slaves, and partly on immovable property. Mortgages of this kind were very common in seafaring business. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895] The merchant who borrowed money from a rich citizen in order to carry on a particular business with it, pledged his ship or the goods with which he dealt, or perhaps both, to his creditor in a formal contract. They endeavoured to obtain as much security as possible by very exact arrangements concerning the object of the journey, the nature of the goods, etc.; moreover, the interest in business of this kind was very high, because the creditor ran the risk of losing his bargain entirely, or in part, by storms, or pirates, or other misfortunes. Mortgages were also given on property in land, and the creditor’s right of ownership was inscribed on stone tablets set up on the property in question, with the name of the creditor and the amount of the debt. In some places the State itself conducted books for mortgages, in which all the property was entered, together with the amount of the mortgages upon it. Here, as in other loans, interest was high, and this was due to the insecurity of trade and the very incomplete development of agricultural conditions. There were no laws against usury; from ten to twenty per cent., or higher if it was for risk at sea, was common, but there were even cases where thirty-six or forty-eight per cent. were taken. Of course, in these circumstances complaints of extortion were made. The arrangement of this money business was chiefly in the hands of the bankers. Their original and chief occupation was the changing of money — the various kinds of coinage which became current through foreign trade; and here they got their profit from the rate of exchange. They also lent money, both small sums and capital for trade and other business undertakings, and this was their share in these monetary transactions. Rich people often invested their money with these bankers, who paid them interest and gave them security or pledges; they then themselves lent the money to men of business, and on account of the risk naturally demanded higher interest than they paid. But even when money was lent direct by a capitalist to a merchant, the mediation of a banker was often resorted to in concluding the contract; for these men were well known to the public on account of their extensive business, and possessed considerable business knowledge. As a rule, though some were known as usurers, and trickery and bankruptcy occasionally occurred, they enjoyed so much confidence that they were gladly engaged as witnesses in business contracts, and requested to take charge of the documents. Money also was deposited with them, for which no particular use appeared at the moment, and which would not be safe if kept at home; of course, if this capital lay idle the banker could pay no interest, but often demanded a sum for taking charge of the deposit. Some of them left their money in the hands of money-changers to increase the business capital, and the extent to which this was done is proved by the fact that the banker Pasion, at the time of Demosthenes, in a business capital of 50 talents , had 11 talents lent by private persons. mining slave Greece was resource poor and overpopulated. They needed to colonize the Mediterranean to get resources. The Greeks processed iron from ore mined on Etruscan lands. Copper came from Cyprus. The Tarsus mountains in present-day Turkey was a source of tin, used to make bronze. Cristian Violatti wrote in Listverse: “Mining has always been a highly profitable activity, and ancient Greece was no exception. The profits from mining were as immense as the risks of working in the mines. It’s no wonder that the Athenians employed slaves for a job so dangerous.

Large profits were made not only from the actual mining activity, but also by those who could supply slave labor. We know that the politician and general Nicias (fifth century B.C.) supplied as many as 1,000 slaves to work in the mines, making 10 talents a year, an income equivalent to 33 percent on his capital. [Source: Cristian Violatti, Listverse, September 29, 2016] “The fate of slaves working in the mines was precarious. Many of them worked underground in shackles, deprived from sunlight and fresh air. In 413 B.C. an Athenian army was captured during a disastrous expedition to Sicily, and all 7,000 Athenian prisoners were forced to work in the quarries of Syracuse. Not one of them survived. Roman historian Diodorus Siculus wrote in the first century B.C. "The men engaged in these mining operations produce unbelievably large revenues for their masters, but as a result of their underground excavations they become physical wrecks...they are not allowed to give up working or have a rest, but are forced by the beatings of their supervisors to stay at their places and throw away their wretched lives...Some of them survive to endure their misery for a long time because of their physical stamina or sheer will power; but because of the extent of their suffering they prefer dying to surviving." [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum] A rude relief on a stone slab from Cyprus is a votive offering for rescue from an accident in quarrying or mining. Above is Apollo seated before an altar. Below, a man is hastening to help another who is standing in front of a large mass of rock or earth. Between them a pickaxe lies on the ground. Probably the relief represents a dangerous fall of rock or earth. The inscription runs: “Diithemis dedicated it to the god Apollo, in good fortune.” [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924] See Separate Articles: SLAVERY IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

TYPES OF SLAVES IN ANCIENT GREECE AND THE WORK THEY DID europe.factsanddetails.com According to legend Magnesia (magnet-bearing stone) was discovered by a shepherd named Magnets in ancient Thessaly along the Aegean Sea when a strange mineral pulled out all the nails out of his shoes. Loadstones made from magnetic rock were used as a medicine and a contraceptive; their magic, the Greeks believed, was powerful enough to force unfaithful wives to admit their transgressions and cure bad breath caused by garlic and onions. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin,∞] The Greeks called amber “ elektron” (the root of the word "electricity"), or "substance of the sun," perhaps because of its golden color and the fact that it absorbed sunlight and gave off heat. According to Greek mythology, it was created from tears shed by Apollo's daughters over the death of their dead brother Phaëton. Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: To the Greeks and Romans, a red pigment known as miltos was a sort of multipurpose supersubstance. Ancient writers, from Theophrastus to Pliny, record that the finegrained, red iron oxide–based material was much sought after for use in decoration, cosmetics, agriculture, medicine, and even boat maintenance. A new study indicates that one of the reasons miltos was so versatile is that not all miltos was created equal. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2019] “An international team analyzed the mineralogy, geochemistry, and even microbiology of miltos samples recovered from the Greek islands of Kea and Lemnos, and has been able to identify subtle variations that made each sample suitable for a particular use. “Different sources produced different types of miltos,” says University of Glasgow archaeologist Effie Photos-Jones. “It was not a pure mineral but rather a combination of minerals. There are also variations in the microorganisms that live in the immediate vicinity of those minerals.” For example, some Kea miltos samples contain microorganisms that would have enhanced their use as a fertilizer. Others contain high concentrations of lead, which could help prevent growth of harmful biofilms and barnacles on ships’ hulls. One sample from Lemnos has traces of titanium dioxide, a known antibacterial compound, making it useful for medicinal purposes. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications. Last updated September 2024

“The Making of the Ancient Greek Economy: Institutions, Markets, and Growth in the City-States” by Alain Bresson and Steven Rendall (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Greek Economy: Markets, Households and City-States” by Edward M. Harris, David M. Lewis, et al. (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to the Ancient Greek Economy”

by Sitta von Reden Amazon.com;

“Ancient Economy” by M. I. Finley (1912-1986) and Ian Morris (1999) Amazon.com;

“Population and Economy in Classical Athens” by Ben Akrigg (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Economy of Classical Athens: Organization, Institutions and Society”

Amazon.com;

“Economy and Society in Ancient Greece” by M. I. Finley , Brent Shaw, et al. (1982) Amazon.com;

“Poverty in Ancient Greece and Rome: Realities and Discourses” (Routledge) by Filippo Carlà-Uhink, Lucia Cecchet, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Open Sea: The Economic Life of the Ancient Mediterranean World from the Iron Age to the Rise of Rome” by J. G. Manning (2024) Amazon.com;

“Mining and Metallurgy in the Greek and Roman World” by John F Healy (1978) Amazon.com;

“Silver for the Gods: 800 Years of Greek and Roman Silver” by Andrew Oliver (1977) Amazon.com;

“Oil, Wine, and the Cultural Economy of Ancient Greece: From the Bronze Age to the Archaic Era” by Catherine E. Pratt (2021) Amazon.com;

“Making Money in Ancient Athens” by Michael Leese (2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Jobs” by Haydn Middleton (2003)

Amazon.com;

“Mycenaean Greece, Mediterranean Commerce, and the Formation of Identity” by Bryan E. Burns (2010) Amazon.com;

“Technology and Society in the Ancient Greek and Roman Worlds” by Tracey Elizabeth Rihll (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Economics of War in Ancient Greece” by Roel Konijnendijk and Manu Dal Borgo | (2024) Amazon.com;

“Economics of Religion in the Mycenaean World: Resources Dedicated to Religion in the Mycenaean Palace Economy” by Lisa Maria Bendall (2007)

Agoras (Marketplaces) in Ancient Greece

Athens Agora

Buildings in Athens Agora

Ancient Greek Seaside Strip Mall

Contempt for Tradesmen in Ancient Greece

Spartan Economy and Frugality

Money in Ancient Greece

coins for Ptolemy II and Ptolemy III The first coins appeared in Lydia, a small kingdom in Asia Minor, around 600 B.C. Coinage was introduced to Asia Minor by the Lydians and was used by several Greek city-states on Asia Minor within a few decades after it first appeared. The Greeks made coins of various denomination in unalloyed gold and silver and the stamped them with images of gods and goddesses.Aristotle on Property

Law Code of Gortyn (450 B.C.) on Property and Inheritance

Banks in Ancient Greece

Bankers and Money-Changers in Ancient Greece

Resources and Mining in Ancient Greece

Magnets, Amber and Miltos