Home | Category: Government and Justice

CRIME AND JUSTICE IN ANCIENT GREECE

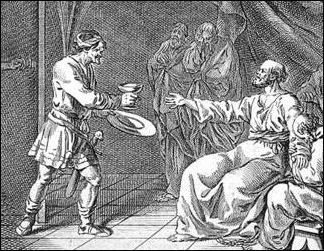

Socrates death Poisoning was a common way of murdering people. King Mithridates VI of Pontus was obsessed with the idea of being assassinated by poison. In an efforts to create a defense against such attacks he took minute amounts of toxins to be build up a tolerance to them and developed a complex compound — called methridatium — comprised of 54 toxins, which was taken by him took regularly and leaders after him who feared assassinations.

According to a myth, Medea murdered the uncle of Jason (of the Argonauts fame) by giving him a bath in a deadly poison that the king thought was going to restore his lost youth. Agamemnon was also murdered in a bathtub. His wife struck him twice on the head with an ax after he returned home from the Trojan War.◂

Laws varied from city to city state. The scholar John Gager, told National Geographic, "With the possible exception of modern America, no society has been more notorious for litigation than classical Athens. Women were not normally allowed to testify in Athenian courts.

In ancient times men sometimes made a pledge by putting their hands on their testicles as if to say, "If I am lying you can cut off my balls." The practice of making a pledge on the Bible is said to have its roots in this practice. Burning garments were used to punish criminals in ancient Greece and Rome. Plato described gruesome tortures involving tunics soaked in pitch. Many sentenced to death were poisoned. Excavations have revealed thimble-size terra cotta vessels in which executioners measured doses of hemlock.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Greek Laws: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Ilias Arnaoutoglou (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek Law” by Michael Gagarin and David Cohen (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Law in Classical Athens” by Douglas M. MacDowell (1986) Amazon.com;

“Early Greek Law” by Michael Gagarin (1989)

Amazon.com;

“Draco's Decrees: Early Greek Legal Codes” by Oriental Publishing Amazon.com;

“Solon the Thinker: Political Thought in Archaic Athens” by John David Lewis (2008) Amazon.com;

"The Laws of Solon: A New Edition with Introduction, Translation and Commentary” by D F Leão and PJ Rhodes (2016) Amazon.com;

“Revenge, Punishment and Anger in Ancient Greek Justice” by Joe Whitchurch (2024) Amazon.com;

“Law, Violence, and Community in Classical Athens” by David J. Cohen (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World: From the Archaic Age to the Arab Conquests” by G. E. M. de Ste. Croix (1981) Amazon.com;

“Athena's Justice: Athena, Athens, and the Concept of Justice in Greek Tragedy” by Rebecca Futo Kennedy (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Just State: Greek and Roman Theories of Justice and Their Legacy in Western Thought” by Benjamin Straumann (2025) Amazon.com;

“Citizenship in Classical Athens” by Josine Blok (2017) Amazon.com;

“Polis: An Introduction to the Ancient Greek City-State” by Mogens Herman Hansen (2006) Amazon.com;

“Classical Athens and the Delphic Oracle: Divination and Democracy” by Hugh Bowden (2005) Amazon.com;

“Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric, Ideology, and the Power of the People” by Josiah Ober (1989) Amazon.com;

Lawyers and Jurors in Ancient Greece

In the 4th century B.C. , Athenian jurors cast their votes in terra-cotta ballot boxes. The ballots, stamped "official ballot," resembled metal tops. Each juror was given two ballots: a solid one represented innocent and a hollow one represented guilty. The ballots were made in such a way that they could be deposited in the ballot box without any one seeing the juror's choice.

The first lawyers were 5th century B.C. “ logographoi”, professional Athenian speech writers who were trained in rhetoric and used their persuasive powers to write speeches to help defendants argue cases before a magistrate, to prepare the details of the case, to advise their clients which courts to use, and to come up with a strategy. They differed from modern lawyers however in that they didn't argue the cases themselves for their clients.

Describing a young lawyer in action, the satirical dramatist Aristophanes wrote: "We take our stand before the bench...Your youngster opens fire by discharging a verbal volley. Then he drags up some poor Methuselah and cross-examines him, baiting word traps, tearing, snaring and curdling him. The old fellow mumbles through his toothless gums and goes off with his case lost." Describing another lawyer in “ Clouds” , Aristophanes wrote: he was a "lawbook on legs, who can snoop like a beagle,/a double-faced, lethal-tongued legal eagle."

Athenian lawyers used many tactics well-known modern attorneys: They raised innumerable facts and details to bolster their own case and obscure the main points of their opponents arguments; they brought in weeping wives and children to solicit sympathy. A judge in one of Aristophanes plays said: "There isn't a form of flattery they don't pour into a jury's ear. And some try pleading poverty and giving me hard luck stories...Some crack jokes to get me to laugh and forget I've got it in for them. And, if I prove immune to all these, they'll right away drag up their babes by the hand." In the same play a judge hears a case concerning a dog accused of stealing cheese from a kitchen. The dog wins acquittal by bring his yowling pups to the stand.

The dikast’s ticket is the ticket of a juryman, Epikrates, entitling him to sit in the ninth court at Athens, of which there were ten in all, and to draw three obols a day, about ten cents, a “living wage,” however. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Courts in Athens

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “The Athenians have other law courts as well, which are not so famous. We have the Parabystum (Thrust aside) and the Triangle; the former is in an obscure part of the city, and in it the most trivial cases are tried; the latter is named from its shape. The names of Green Court and Red Court, due to their colors, have lasted down to the present day. The largest court, to which the greatest numbers come, is called Heliaea. One of the other courts that deal with bloodshed is called "At Palladium," into which are brought cases of involuntary homicide. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

ruins of the Athens Agora Law Court

“All are agreed that Demophon was the first to be tried there, but as to the nature of the charge accounts differ. It is reported that after the capture of Troy Diomedes was returning home with his fleet when night overtook them as in their voyage they were off Phalerum. The Argives landed, under the impression that it was hostile territory, the darkness preventing them from seeing that it was Attica. Thereupon they say that Demophon, he too being unaware of the facts and ignorant that those who had landed were Argives, attacked them and, having killed a number of them, went off with the Palladium. An Athenian, however, not seeing before him in the dark, was knocked over by the horse of Demophon, trampled upon and killed. Whereupon Demophon was brought to trial, some say by the relatives of the man who was trampled upon, others say by the Argive commonwealth.

“At Delphinium are tried those who claim that they have committed justifiable homicide, the plea put forward by Theseus when he was acquitted, after having killed Pallas, who had risen in revolt against him, and his sons. Before Theseus was acquitted it was the established custom among all men for the shedder of blood to go into exile, or, if he remained, to be put to a similar death. The Court in the Prytaneum, as it is called, where they try iron and all similar inanimate things, had its origin, I believe, in the following incident. It was when Erechtheus was king of Athens that the ox-slayer first killed an ox at the altar of Zeus Polieus. Leaving the axe where it lay he went out of the land into exile, and the axe was forthwith tried and acquitted, and the trial has been repeated year by year down to the present. Furthermore, it is also said that inanimate objects have on occasion of their own accord inflicted righteous retribution upon men, of this the scimitar of Cambyses affords the best and most famous instance.1 Near the sea at the Peiraeus is Phreattys. Here it is that men in exile, when a further charge has been brought against them in their absence, make their defense on a ship while the judges listen on land. The legend is that Teucer first defended himself in this way before Telamon, urging that he was guiltless in the matter of the death of Ajax. Let this account suffice for those who are interested to learn about the law courts.

In 2012, an archaeologist said he found what he thought was a murder court in Athens. Yannis Stavrakakis wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Next to the Acropolis' south slope, archaeologists have discovered possible evidence of one of ancient Athens’ murder courts. During several years of excavation, archaeologist Xristos Kontoxristos uncovered artifacts dating from the prehistoric through late Roman periods. He was particularly intrigued by a pedestal formed of sculpted lions’ legs, upon which sat two marble slabs forming a very large table or podium that he dated to the late Classical or early Hellenistic period (about 400–300 B.C.). Near the podium, Kontoxristos found a piece of copper of the type that citizens may have used to record legal verdicts. Kontoxristos suggests that the podium may be part of a complex that includes a very large building foundation and portico dating to the same period—first identified in the 1960s as the Palladium. According to second-century A.D. geographer Pausanias, the Palladium was the court in which cases of involuntary homicide and killing of noncitizens were tried. Kontoxristos stresses that the identification of pedestal and building is not definitive, but he hopes to uncover additional evidence. [Source: Yannis Stavrakakis, Archaeology , Volume 65 Number 4, July/August 2012]

Trial of Socrates

In Socrates trial there were no lawyers and Socrates defended himself, saying simply he was a humble seeker of truth. One by one his accusers, limited by the time established by a water clock, addressed the 501 member jury. His chief accuser, Meletus, was. Socrates said, “an unknown youth with straight hair and a skimpy beard.”

Socrates, then 70 years old, "gave a bumbling performance. He was no orator" said Historian M.I. Finley. In the trial, Socrates said that people were threatened by his self appointed role as "the gadfly of Athens." Socrates's questioning of the existence of the gods, cross-examination of conventional wisdom and criticizing of the government had won him many enemies. Some say he was used as a scapegoat for Athens' loss in the Peloponnesian War.

The jury found Socrates guilty by a vote of 281 to 220 and advocated the death penalty. Socrates was given an opportunity to suggest an alternative punishment. He said he deserved to be treated like an Olympic champion and receive a life-time pension. The jury was not amused and he was sentencing to die by drinking a cup off hemlock.

Accountability, Corruption and Bribes in Ancient Greece

John McK. Campo, a classic professor at Randolph-Macon College in Virginia, wrote in the New York Times: “The Athenians were better than we are at enforcing accountability in their public officials. They had an examination to check the qualifications of an individual before entering office (a "dokimasia” ), but they also had a formal rendering of accounts at the end of a term of office (“euthynai”) and ostracism in the meantime.”

Legislators were wined and dined at public expense using official drinking cups and tableware that one can see today in Athens.

Bribe-taking was not taken lightly in ancient Greece. In “Laws” Plato said that it merited “disgrace”. In Athens it was grounds for having one’s citizenship revoked. Demosthenes was found guilty of accepting bribes in 324 B.C. and was fined 50 talens — which by some estimated is equal to $20 million in today’s money — and ultimately got off with being exiled. Other officials were executed for taking bribes, University of Texas classic professor Michael Gagarin told the New York Times, “Bribery was taken very seriously and certainly could lead to capital punishment.”

Tyrants and Ostracism in Ancient Greece

ostracism token

The first Greek "tyrants" were not tyrants as we think of them today. They were rulers who ousted local oligarchies with the support of the people. On one level they raised expectations of accountability but on other they were often corrupted by power and evolved in despots, who themselves were overthrown with the support of the people.

Politicians who fell out of favor could be ostracized — exiled for 10 years — by a vote of the assembled citizens, who cast their ballots by scratching the name of the ostracized person on a shard of pottery, or “ ostrakon” (source of the word ostracize) used as ballots. The measure was set up not to punishment in any harsh or cruel way; the idea was simply to remove them from the political arena and public life. Many prominent Athenian politicians were ostracized.

Ostracism was introduced by Cleisthenes in 508 B.C. after exiling the tyrant Hippias, reportedly with the aim of preventing the emergence of a dictator who might seize powerful unlawfully by whipping up public discontent. It was used from 487 to 417 B.C., which some historians have pointed out was when Athens was at its peak, According to the procedure, citizens of ancient Athens were instructed to gather once a year and asked if they knew of anyone aiming to be a tyrant. If a simple majority voted yes the members were dispersed and told to come back in two months time and used an “ostrakon” to scratch the name of the citizen whom they deemed most likely to become a tyrant. The person who received the most votes in excess of a set number was expelled from the city-state for 10 years. This simple act is regarded by some historians as the foundation of democracy in ancient Athens.

Pottery shards that were used for secret votes have been found by archaeologists. Among the names that have been found on ostrakons are Pericles, Aristides and Thucydides. Pericles was nearly ostracized over opposition to his plan to build the Parthenon. A pile of 190 shards with the name Themosticles written on them by 12 individuals found in a well and is believed to be one of the first examples of vote rigging.

There were abuses of the system, notibly when strong politicians wanted to oust rivals. Pericles used the system to get rid of his main challenger, Thucydides. Ostracism itself was dropped when the powerful politicians Alcibiades and Nikias ganged to on Hyperbolos, a rival to both of them, and had him exiled.

RELATED ARTICLES: See Ostracism Under GOVERNMENT IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Defense Against a Charge of Black Magic

The Apologia (Apulei Platonici pro Se de Magia) is the version of the defense presented in Sabratha, Libya, in A.D. 158-159, before the proconsul Claudius Maximus, by Apuleius accused of the crime of magic. Apuleius was a priest and an initiate in several Greco-Roman mysteries, including the Dionysian Mysteries. In his defense he said: “For my part, Claudius Maximus, and you, gentlemen who sit beside him on the bench, I regarded it as a foregone conclusion that Sicinius Aemilianus would for sheer lack of any real ground for accusation cram his indictment with mere vulgar abuse; for the old rascal is notorious for his unscrupulous audacity, and, further, launched forth on his task of bringing me to trial in your court before he had given a thought to the line his prosecution should pursue. Now while the most innocent of men may be the victim of false accusation, only the criminal can have his guilt brought home to him. It is this thought that gives me special confidence, but I have further ground for self-congratulation in the fact that I have you for my judge on an occasion when it is my privilege to have the opportunity of clearing philosophy of the aspersions cast upon her by the uninstructed and of proving my own innocence. Nevertheless these false charges are on the face of them serious enough, and the suddenness with which they have been improvised makes them the more difficult to refute. [Source: Apuleius, translated by H. E. Butler, MIT]

Curse inscription “For you will remember that it is only four or five days since his advocates of malice prepense attacked me with slanderous accusations, and began to charge me with practice of the black art and with the murder of my step-son Pontianus. I was at the moment totally unprepared for such a charge, and was occupied in defending an action brought by the brothers Granius against my wife Pudentilla. I perceived that these charges were brought forward not so much in a serious spirit as to gratify my opponents' taste for wanton slander. I therefore straightway challenged them, not once only, but frequently and emphatically, to proceed with their accusation...The result was that Aemilianus, perceiving that you, Maximus, not to speak of others, were strongly moved by what had occurred, and that his words had created a serious scandal, began to be alarmed and to seek for some safe refuge from the consequences of his rashness.

“Therefore as soon as he was compelled to set his name to the indictment, he conveniently forgot Pontianus, his own brother's son, of whose death he had been continually accusing me only a few days previously. He made absolutely no mention of the death of his young kinsman; he abandoned this most serious charge, but — to avoid the appearance of having totally abandoned his mendacious accusations — he selected, as the sole support of his indictment, the charge of magic — a charge with which it is easy to create a prejudice against the accused, but which it is hard to prove....

“I rely, Maximus, on your sense of justice and on my own innocence, but I hope that in this trial also we shall hear the voice of Lollius raised impulsively in my defence; for Aemilianus is deliberately accusing a man whom he knows to be innocent, a course which comes the more easy to him, since, as I have told you, he has already been convicted of lying in a most important case, heard before the Prefect of the city. Just as a good man studiously avoids the repetition of a sin once committed, so men of depraved character repeat their past offence with increased confidence, and, I may add, the more often they do so, the more openly they display their impudence. For honour is like a garment; the older it gets, the more carelessly it is worn. I think it my duty, therefore, in the interest of my own honour, to refute all my opponent's slanders before I come to the actual indictment itself.

“For I am pleading not merely my own cause, but that of philosophy as well, philosophy, whose grandeur is such that she resents even the slightest slur cast upon her perfection as though it were the most serious accusation. Knowing this, Aemilianus' advocates, only a short time ago, poured forth with all their usual loquacity a flood of drivelling accusations, many of which were specially invented for the purpose of blackening my character, while the remainder were such general charges as the uninstructed are in the habit of levelling at philosophers. It is true that we may regard these accusations as mere interested vapourings, bought at a price and uttered to prove their shamelessness worthy of its hire.

“It is a recognized practice on the part of professional accusers to let out the venom of their tongues to another's hurt; nevertheless, if only in my own interest, I must briefly refute these slanders, lest I, whose most earnest endeavour it is to avoid incurring the slightest spot or blemish to my fair fame, should seem, by passing over some of their more ridiculous charges, to have tacitly admitted their truth, rather than to have treated them with silent contempt. For a man who has any sense of honour or self-respect must needs — such at least is my opinion — feel annoyed when he is thus abused, however falsely. Even those whose conscience reproaches them with some crime, are strongly moved to anger, when men speak ill of them, although they have been accustomed to such ill report ever since they became evildoers. And even though others say naught of their crimes, they are conscious enough that such charges may at any time deservedly be brought against them. It is therefore doubly vexatious to the good and innocent man when charges are undeservedly brought against him which he might with justice bring against others. For his ears are unused and strange to ill report, and he is so accustomed to hear himself praised that insult is more than he can bear.”

Herodotus on the Trial by Ordeal of the Getae

Zalmoxix Aleksandrovo, a Thracian Getae king

Herodotus wrote in Histories IV, 93-6: The Getae “pretend to be immortal’ and are “the bravest and most just Thracians of all. Their belief in their immortality is as follows: they believe that they do not die, but that one who perishes goes to the deity Salmoxis, or Gebeleïzis, as some of them call him. Once every five years they choose one of their people by lot and send him as a messenger to Salmoxis, with instructions to report their needs; and this is how they send him: three lances are held by designated men; others seize the messenger to Salmoxis by his hands and feet, and swing and toss him up on to the spear-points. If he is killed by the toss, they believe that the god regards them with favor; but if he is not killed, they blame the messenger himself, considering him a bad man, and send another messenger in place of him. It is while the man still lives that they give him the message. Furthermore, when there is thunder and lightning these same Thracians shoot arrows skyward as a threat to the god, believing in no other god but their own. [Source: Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920]

“I understand from the Greeks who live beside the Hellespont and Pontus, that this Salmoxis was a man who was once a slave in Samos, his master being Pythagoras son of Mnesarchus; [2] then, after being freed and gaining great wealth, he returned to his own country. Now the Thracians were a poor and backward people, but this Salmoxis knew Ionian ways and a more advanced way of life than the Thracian; for he had consorted with Greeks, and moreover with one of the greatest Greek teachers, Pythagoras; therefore he made a hall, where he entertained and fed the leaders among his countrymen, and taught them that neither he nor his guests nor any of their descendants would ever die, but that they would go to a place where they would live forever and have all good things. [Source: Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920]

“While he was doing as I have said and teaching this doctrine, he was meanwhile making an underground chamber. When this was finished, he vanished from the sight of the Thracians, and went down into the underground chamber, where he lived for three years, while the Thracians wished him back and mourned him for dead; then in the fourth year he appeared to the Thracians, and thus they came to believe what Salmoxis had told them. Such is the Greek story about him. Now I neither disbelieve nor entirely believe the tale about Salmoxis and his underground chamber; but I think that he lived many years before Pythagoras; and as to whether there was a man called Salmoxis or this is some deity native to the Getae, let the question be dismissed.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024