Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

ANCIENT GREEK CLOTHES

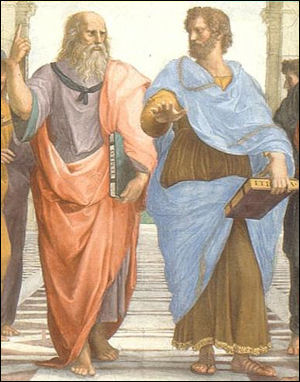

Raphael's vision of Greek clothing Trousers and shirts were not worn by the Greeks or Romans. Greeks wore a short diaper and a sheet for clothing. People generally didn't wear underwear in the modern sense. Through the use of pins, buttons, shoulder harness, and waist cinches the Greeks were able to produce a variety of clothing from what were otherwise pieces of draped cloth. Garments were often held in place with “ porpai” , dress pins that were sometimes razor sharp and made of gold. Designers such Fortuny, Yves saint Laurent and Madame Grez were much inspired by Greek clothes.

Generally speaking, we may distinguish, both in male and female Greek costume, two kinds of garments: 1) those which are cut in a certain shape and partly stitched, and 2) mantles of various shapes which are draped on the figure and only acquire their form by means of this draping. This distinction holds good with few exceptions throughout the whole history of Greek costume; and, generally speaking, it is the lower garments which are stitched, while the upper garments are draped. Yet we must observe that, while male clothing is, as a rule, confined to two garments, we very often find in female costume a third, or even a fourth, belonging sometimes to the first and sometimes to the second of the above-mentioned classes. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The names which were used throughout almost the whole of Greek antiquity for the two chief articles of dress are: 1) chiton, for the inner garment, and 2) himation (or chlaina), for the upper garment worn over the chiton. These terms are used for both male and female garments.. Several other designations are used. The word himation is not found in the Homeric period, around 700 B.C., but the cloak which is worn over the chiton is.

Although there the strong contrast today between between the dress of men and women in Greek antiquity both had essentially the same elements, sometimes even the same shape. This was not carried so far that a woman could simply have put on a man’s under garment; in fact, even the Homeric epics distinguish the woman’s peplos from the man’s chiton. Unfortunately, both the shape and the mode of wearing the Homeric peplos are matters of dispute which cannot be satisfactorily settled by the words of the epic. The long female chiton was not essentially different from the long male chiton, It descended to the feet, fitting closely and without folds to the figure, and was provided with an opening for head and arms.

Harold Koda of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The richness and variety of the costumes represented in ancient Greek art are often the result of simple manipulations of the three basic garment types: the chiton, the peplos, and the himation. Positioning a waist cinch or a shoulder harness and removing a fibula introduced to the ancient wardrobe the possibility of innumerable effects.” [Source: Harold Koda, The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

Greek literature features some unusual garments. In Euripides “ Medea” a bride is sent a wedding gift of a gown that tears of her flesh and a headpiece that spontaneously combusts leaving her just bits of bone and charred remains.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece, Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Costumes of the Greeks and Romans” by Thomas Hope (1962) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek, Roman & Byzantine Costume” by Mary G. Houston (2011)

Amazon.com;

“Women's Dress in the Ancient Greek World” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2023) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Jewellery” by Filippo Coarelli (1970) Amazon.com;

“Dress in Mediterranean Antiquity: Greeks, Romans, Jews, Christians” by Alicia J. Batten, Kelly Olson (2021) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Garments: Textiles in Greek Sanctuaries in the 7th to the 1st Centuries BC” by Cecilie Brøns (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Book of the Feet; a History of Boots and Shoes, With Illustrations of the Fashions of the Egyptians, Hebrews, Persians, Greeks and Romans” by Joseph Sparkes Hall (1847) Amazon.com;

“Textiles in Ancient Mediterranean Iconography” by Susanna Harris, Cecilie Brøns, Marta Zuchowska Amazon.com;

“Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece” by Mireille M. Lee (2015) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Dress from A to Z” by Liza Cleland, Glenys Davies, et al. (2007) Amazon.com;

“History of Costume: From the Ancient Mesopotamians to the Twentieth Century” by Blanche, Payne (1997). Amazon.com;

“How the Greeks and Romans Made Cloth” (Cambridge School Classics Project)

Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks” (The Greenwood Press Daily Life Through History Series) by Robert Garland (2008), Amazon.com;

“The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” (Classic Reprint) by Alice Zimmern (1855-1939) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks: Life and Customs” by E. Guhl and W. Koner (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Life of the Ancient Greeks, With Special Reference to Athens”

by Charles Burton (1868-1962) Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Life in Ancient Greece” by Leslie Adkins and Roy Adkins (1998) Amazon.com;

Underwear and Bras in the Ancient Greece

Men and women sometimes wore triangular loincloths, called perizoma, as underwear. As early as 2500 B.C. women in Minoa wore bras that completely lifted the a woman's breasts out of her garments. Greek and Roman women strapped in their breasts with bands of cloth that flattened their chest and reduced their breast size. Women often wore a strophion, the bra of the time, under their garments and around the mid-portion of their body. The strophion was a wide band of wool or linen wrapped across the breasts and tied between the shoulder blades.

strophions on "bikini girls" mosaic, found by archaeological excavation of the AD 4th century ancient Roman villa del Casale near Piazza Armerina in Sicily

Melissa Sartore wrote in National Geographic: Egyptians had schenti, Romans wore subligaculum...The earliest form of underwear was a loincloth. Prehistorically, loincloths were worn by men and women, crafted out of strips of fabric that ran between one's legs and were fastened around the waist. Ancient Egyptians fashioned triangular swatches of linen with strings at the ends.. Nudity was much more acceptable in ancient Greece, but even there, underwear comparable to that of the Egyptians called perizoma might be worn. Meanwhile, ancient Romans had their own undergarments to sport underneath a tunic, toga, or robe: Worn by the mid-2nd century A. D. and adapted from the ancient Etruscans, Roman subligaculum could resemble a loincloth or look more like a pair of shorts. [Source:Melissa Sartore, National Geographic, January 10, 2024]

Erin Blakemore wrote in National Geographic History: Though it’s unclear when the first of the bra’s many precursors was invented, historians have found references to bra-like garments in ancient Greek works like Homer’s Iliad, which depicts the goddess Aphrodite removing a “curiously embroidered girdle” from her bosom, and Aristophanes’ Lysistrata, in which a woman withholding sex from her husband teases him by saying she’s taking off her strophion, clumsily translated as “breast-band.” Scholars are divided on whether Greek and Roman women wore bra-like garments for support, style, or both. Historian Mireille Lee writes that though the strophion had sexual and gendered connotations, it’s difficult to determine exactly what, if anything, ancients wore beneath their clothes — there’s only a single artistic depiction from the time that shows a woman wearing a strophion beneath clothing. [Source Erin Blakemore, National Geographic History, October 4, 2023]

A tan, limestone statuette shows a male votary from the legs up with Cypriot loincloth and an Egyptian crown. It dates to the first half of the 6th century B.C. and measures 44. 5 x 21. 3 x 8. 6 centimeters (17 1/2 x 8 3/8 x 3 3/8 inches). A white statue of a woman with a gold bikini-like top and gold, bikini-like bottoms is a Roman marble copy of a Hellenistic original found in the House of Julia Felix (Praedia di Giulia Felice) in Pompeii (A.D. 1st century). It is on display in the Secret Cabinet (Gabinetto Segreto) in the National Archaeological Museum in. Naples. Her arm is resting on the head of a child, also in statue form. A smaller child is seen crouched down under her foot, holding up it's hand to touch the foot.

Drapery on Ancient Greek Clothing

Ancient Greek monuments of show signs of drapery, generally of an artificial, exaggerated, and pedantic kind. It must have been the fashion at that time, that is, from the sixth till nearly the middle of the fifth century, to lay the folds of men’s dress, as well as of women’s, in symmetrically parallel lines. In pictures the lower edges of dresses and cloaks show various regularly cut-out points, while on the inner side there are many small zigzag folds arranged with laborious symmetry. This may be partly due to the artistic style, which at that period inclined to over-elaboration; yet it is impossible to doubt that we find here not only an expression of archaic art, but also the representation of a dress laboriously and artificially folded, stiffened, and ironed, in which the folds were produced by external aids, such as ironing, starching, pressing, even stitching of the stuff laid in folds, or sewing such folds on to the material. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

We cannot determine when this custom began in Greece. In works of art we find it comparatively late in the sixth century B.C.; yet, as Helbig remarks, it is by no means impossible that this fashion existed at a far more ancient period, since the custom of laying material in artificial folds by means of stiffening or ironing was already known in Egypt in 4000 B.C.; and it therefore seems extremely probable that the Phoenicians adopted the practice at a very early period, and introduced it into Greece. It is a very natural assumption that this mode of draping would in the first instance be adopted for linen material, and that it would therefore be introduced among the Greeks with the linen chiton, which took the place of the woollen one formerly worn.

On the other hand, however, it is probable that, as woollen clothing was afterwards worn as well as linen, they attempted to ornament this in similar fashion by artificial folds; the works of art, however, show that these folds were far less in quantity and less sharply defined in woollen clothing than in linen, which is naturally much better adapted for the purpose.

Apart from the folds, the clothes now became wider and more comfortable, and were less closely girt round the hips. The chiton is still a garment made by sewing, and the long differs from the short only in length, not in shape. Both are, as a rule, so cut as to be sewn together regularly below the girdle; above the girdle they are sometimes provided with a slit on one side to facilitate putting on. They usually have sleeves, sometimes short, sometimes long; these are either fastened all round, or, as is also the case in female dress, open at the top and fastened by pins or buttons. In this case the chiton is sewn in such a manner as to be all in one above the girdle as far as the sleeve, and open at the top, so that the slits for the arms and neck are connected; the wearer puts the chiton over his head, draws up the sleeve on the upper arm, and thus supplies the opening for the neck. Besides this, there is often an ornamental arrangement such as we find in the female dress of the same period a puff of regular folds (kolpos), formed by drawing up the dress over the girdle and letting the piece drawn up all round fall again over the girdle; and, in addition, a bib falling over the breast in zig-zag folds, which appears, as a rule, to be a separate piece sewn on the dress at the opening of the neck. In another image we observe the kolpos and bib over the short chiton of Hermes in the center, the bib also over the long chiton of Paris, and of Tyndareus.

Ancient Greek Men’s Clothes

Greek, Macedonian and Roman men favored toga-like garments while ancient Chinese and Persian men often wore trousers. Greek men wore two kinds of clothing: a cloak draped in various ways around the body with "varying degrees of modesty" (the “ himation” ), and a cloak draped around one shoulder and pinned to the other (the “ chlamys” ). Belts were sometimes worn and excess material was stuffed into a pouch.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Men in ancient Greece customarily wore a chiton similar to the one worn by women, but knee-length or shorter. An exomis, a short chiton fastened on the left shoulder, was worn for exercise, horse riding, or hard labor. The cloak (himation) worn by both women and men was essentially a rectangular piece of heavy fabric, either woolen or linen. It was draped diagonally over one shoulder or symmetrically over both shoulders, like a stole. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art. "Ancient Greek Dress", Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org]

Young men often wore a short cloak (chlamys) for riding. The chlamys was a seamless rectangle of woolen material worn by men for military or hunting purposes. It was worn as a cloak and fastened at the right shoulder with a brooch or button. The chlamys was typical Greek military attire from the 5th to the 3rd century BC.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK MEN'S CLOTHES europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Greek Women’s Clothes

The earliest garment for women which we know of was a chiton of wool without sewing. This was a large rectangular piece of cloth considerably wider and longer than the body. It was folded through the middle lengthwise, so that one side was closed and the other open. The top, again, was generally folded over, this hanging portion being called “apoptygma.” Long pins inserted with the points upwards, or fibulae, were used to fasten the double edge on the shoulders, and a girdle was usually worn to hold the edges of the open side in place. If the chiton were still too long, part of the cloth was drawn up through the girdle into a blouse called “kolpos.” From early representations in art, it seems that clothing for both men and women was at first rather narrow and was often covered with woven or embroidered patterns. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Athena-Artemis kore wearing peplos

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The diversity of women's apparel in ancient Greece can be reduced to three general garment types: the chiton, the peplos, and the himation Structurally, the most elemental dress type is the chiton, which is constructed in several ways. The most commonly represented is accomplished by stitching two rectangular pieces of fabric together along either sideseam, from top to bottom, forming a cylinder with its top edge and hem unstitched. The top edges are then sewn, pinned, or buttoned together at two or more points to form shoulder seams, with reserve openings for the head and arms. [Source: Harold Koda, The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

The chiton was made of a much lighter material, usually imported linen. It was a very long and very wide rectangle of fabric sewn up at the sides, pinned or sewn at the shoulders, and usually girded around the waist. Often the chiton was wide enough to allow for sleeves that were fastened along the upper arms with pins or buttons. Both the peplos and chiton were floor-length garments that were usually long enough to be pulled over the belt, creating a pouch known as a kolpos. Under either garment, a woman might have worn a soft band, known as a strophion, around the mid-section of the body. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art. "Ancient Greek Dress", Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The cloak (himation) worn by both women and men was essentially a rectangular piece of heavy fabric, either woolen or linen. It was draped diagonally over one shoulder or symmetrically over both shoulders, like a stole. The girdle was worn rather low down, not immediately under the breast or round the waist, but round the hips, and fell down somewhat in front. The peplos was put on by means of a slit between the breasts, which often descended as far as the feet, and was fastened by a large number of fibulae, or hooks. Some scholars thinks that this fashion was due to Asian influence, since such openings are very commonly found on monuments representing Asian nations.

The himation was always orthogonal, unlike the Roman toga, which had some shaping. Like the toga, however, it appears to have had a variety of cultural meanings, depending on its proportion and how it was worn. Generally, when worn by women, it was a garment of decorous modesty, but it has been shown on hetaerae as a device for provocation. In the seventh and sixth centuries there were various ways of arranging the himation; as a shawl, or as a scarf fastened on one shoulder. An archaic statue of a woman shows her wearing it doubled and fastened on one shoulder over an Ionic chiton of soft, crinkled linen. Gradually a simpler and more beautiful arrangement was adopted; the himation was laid across the back with one corner over the left shoulder, then folded around the front of the body, passing either over or under the right arm according to the wearer’s wish, and the end thrown over the left shoulder, from which it hung down the back, kept in place by a weight in the corner. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Women sometimes wore an epiblema (shawl) over the peplos or chiton. While there are a number of scarf, veil, shawl, and mantle forms, each with a distinct nomenclature, it is the himation with its range of draping and wrapping possibilities that has been the most evident source of later evocations of Hellenistic dress. Some Greek women donned a flat-brimmed hat with a high peaked crown. Like men, women wore sandals, slippers, soft shoes, or boots, although at home they usually went barefoot

Peplos

Greek women initially wore a “ peplos” , a garment consisting of two bed sheet-size pieces of cloth, one in the front and one in the back, that were held together with two dagger-like pins, one over each shoulder. According to legend this garment was popular until Athens fought a war with the city-state of Aegina. During the battle every man was killed but one. When the survivor delivered the news to the wives and mothers of dead men, the women took out their anger with their dagger-pins, stabbing the man to death. Greek officials were so outraged by the behavior of women, they forced the women to wear Ionic style “ chintons” . These garments were virtually the same as the peplos except they were fastened together with buttons not lethal pins. Women could also wear a shawl called an epiblema. [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum,||]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The peplos was simply a large rectangle of heavy fabric, usually wool, folded over along the upper edge so that the overfold (apoptygma) would reach to the waist. It was placed around the body and fastened at the shoulders with a pin or brooch. Openings for armholes were left on each side, and the open side of the garment was either left that way, or pinned or sewn to form a seam. The peplos might not be secured at the waist with a belt or girdle. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art. "Ancient Greek Dress", Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The peplos is perhaps a more distinctively Greek garment than the chiton, insofar as the chiton's reductive construction has similarities to apparel types in a number of other cultures and times. However, the peplos has several characteristics that distinguish it from other clothing traditions. Made of one large rectangular piece of cloth, it was formed into a cylinder and then folded along the topline into a deep cuff, creating an apoptygma, or capelet-like overfold. Although there are rare instances of chitons represented with overfolds, a garment is not a peplos unless it has been draped with an apoptygma. The neckline and armholes of the peplos were formed by fibulae, broochlike pins that attached the back to the front of the garment at either shoulder. Of all the identifying characteristics of a peplos, the fastening of its shoulders with fibulae is its single defining detail. [Source: Harold Koda, The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

Changing Fashions in Ancient Greece

If the vase painters are to be relied on, especially in the arrangement of the girding, the fashion at Athens in the middle of the fifth century B.C. was still rather heavy and awkward. It was not until the excessive fulness of the girding was limited that it developed that regular and truly noble dress which we admire in the female figures of classic art and the following period. Still the dress is by no means uniform, for the same chiton can be worn in various ways, according to the arrangement of the girding and bib. There were, in particular, two methods. The one was to cover the body from the feet to the shoulders with a piece of stuff, and to fasten this by drawing the points of the folded back piece over the shoulders and hooking them to the points of the front piece, which was also doubled back. Then the extra piece fell down at the back and front, and the girdle was passed over it. The stuff was then drawn up a little over the girdle, while the ends of the garment fell down over the hips. Strictly speaking, the kolpos here fell over the bib. The second plan was to take a longer piece of the chiton than was required below the girdle, so that the remainder fell on the ground; the upper part was drawn up to the shoulders and fastened there by fibulae, either in such a way that these were visible (in that case the doubled pieces were fastened together), or so that the pins were hidden by the front piece. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The bib then fell freely over the breast and back till a little above the waist, the superfluous piece below was drawn up over the girdle. The manner of arranging this kind of dress, which is the commoner, is very clearly seen in the bronze statue from Herculaneum. The girl, who is in the act of dressing herself, has already girded the chiton, and is now arranging the bib; she has fastened it on the left shoulder and is now drawing the folded back piece over the right shoulder with her right hand, in order to pin to it the front piece, which she holds in her left hand in such a way that the back piece may fall over the front piece. The points of both then fall over the hips to right and left a little more than half-way down the front breadth. To complete her dress, the girl will then draw up part of the garment, which is too long for walking, over the girdle, and this will appear below the bib. In the dress of the best period this puffing does not fall as low as before. It is so arranged that the folds fall lower on the sides than in the middle, so that its lines may follow the outline of the bib, the points of which fall lower at the sides. Thus originated that beautiful costume, inspired by a truly artistic spirit, which we admire in the best Attic works of the age of Pheidias.

Greek travelling costume, comprised of a chiton, a chlamys, sandals, and a petasos hat hanging in the back

With this dress sleeves, like those above described, are sometimes, but not always, worn. They are usually half-sleeves, with openings fastened by buttons or fibulae, not pieces separately sewn on, but part of the actual chiton. The last-described form of the chiton, which formed the kolpos and bib by means of the girdle and pins, continued in the next period, and seems not only to have extended throughout Greece, but also throughout later Greek antiquity down to the Roman period. But there were also several other styles of dress, distinguished partly by their shape, partly by the manner of wearing. Thus, for instance, the general form of the chiton was retained, but the dress was made more comfortable by the separate construction of the bib, which, as we observed, was probably the case at an earlier period too, and by sometimes omitting it altogether. Sometimes, again, only a light chiton was worn without any kolpos or bib, either with a girdle which was sometimes worn above the waist. Afterwards it was not unusual for the bib to fall below the girdle, while the kolpos was entirely absent, or else fell above the bib. In the graceful female figure in one image there is another peculiarity. Here, the chiton is open at one side, even below the hips, which was not the case with the ordinary dress, especially that worn out of doors. It is probable that this was the original form of the so-called Doric chiton, for it is thus that the Doric maidens were dressed, and on this account were mockingly described as “showing their hips.” In the ideal figures the chiton of Artemis and the Amazons, though shorter, is of the same kind. The form of the chiton fastened together all round originated so early that we only find the kind open at the side in rare instances on the oldest monuments. This chiton corresponds in shape most closely to the short male chiton; like this, it often only extends to the knees, and is fastened on the shoulders by pins without forming the bib. The dress with regular sleeves is also found in the later costume, either connected with the under garment or specially constructed so as to cover only the upper part of the body. It was fastened together all round, and opened at the sleeves, which were constructed by buttons.

The himation continued to be the usual upper garment. In the older costume of the sixth and fifth centuries it is often treated as a scarf in the manner above described, with two points falling down in front over the shoulders, but afterwards women began to wear the himation in the same way as men, either enveloping the arms entirely or leaving the right arm free. A third mode of wearing the himation, which, however, is commoner in older than in later costume, is to draw it from the right shoulder across the breast to the left hip, leaving the left breast uncovered, and letting the points fall down on the right side of the body. In the pictures it often looks as though the himation were fastened on the shoulder by pins, or even stitched together. We also find a light kind of shawl, put on something in the manner of the scarf worn by ladies some forty or fifty years ago. In fact, there seem to have been many varieties of female dress in the Alexandrine period, but we are not intimately acquainted with the details, as our principal authorities, the vase pictures, at that time no longer confined themselves as strictly as in the older periods to the prevailing fashion. In one of Theocritus’ idylls a woman puts on first her chiton, then a peronatris (a robe fastened by clasps) of costly material, and over that an ampechonion. It is not clear what sort of garment this peronatris was. On the other hand, the terra-cottas of that period often represent graceful female forms in walking dress, that is, in the chiton and himation. We see a woman in a long dress with a train, wearing over it a cloak drawn over her head in such a manner that only her face is visible. To promote freedom of motion her cloak is drawn up over both arms, which are closely enveloped. In a similar matron-like dress is the lady represented in the terra-cotta figure, No. 28. She holds up her long himation daintily with both hands, to enable her to walk more easily.

We cannot with certainty prove the existence of a chemise, since those expressions which are generally thus interpreted appear to relate to different kinds of chitons. Sometimes we see in vase pictures representing scenes from the baths short garments with little sleeves, which cannot well be anything but chemises, worn under the actual chiton. We must not, however, assume that these were universally worn; far commoner was the band called strophion, corresponding to the modern corset, used to check the excessive development of the breasts, or to hold them up when the firmness of youth was gone.

In the fourth century B.C. a gradual decline is again observable, and after the time of Alexander the Great rich designs, sometimes introducing figures, become commoner, even in purely Hellenic dress. Numerous examples on works of art show us the unaesthetic and absurd side of this fashion. The elaborate patterns give a disturbing appearance to the whole figure; the outline of the body is completely hidden by the dress; and when the drapery is disturbed or folded, in the case of borders or materials covered with figures, the result is sometimes very ridiculous.

Doric and Ionic Styles of Clothing

During the seventh and sixth centuries the rich and artistic Ionian cities had a great influence on the customs of Greece, and from them the ladies of Athens adopted the linen chiton, which was wider and was sewed on the sides. The additional width was sometimes used to form sleeves by catching the two pieces together at the top in three or four places, with sewing, buttons, or small pins. Long sleeves sewn in were occasionally worn, but were exceptional rather than customary, so that artists often represent barbarians with sleeves to distinguish them from Greeks. On one kotyle a woman is hown wearing a spotted chiton with long, close-fitting sleeves. At this period men as well as women at times wore the apoptygma and kolpos, but the man’s chiton was generally short.

After the Persian Wars, as the result of the strong reaction against Eastern fashions, men and women both adopted the woolen Doric chiton again, and for men it remained the universal dress, being now short and without apoptygma and kolpos. Still, the adoption of the Doric chiton did not imply a violent change, for working people had worn it continuously and it was the usual dress for young girls. Old men, priests, charioteers, and officials on public occasions continued to wear the long Ionic chiton, and both were in use by ladies at the same period. It should be added that at this time the two types were often worn together, the Ionic forming an undergarment with short sleeves, and the Doric, a sleeveless gown. This costume is frequently seen on grave-reliefs.

The woman’s Doric chiton of this time may be seen in the statue of Eirene. It is worn without a girdle by the young girl on a gravestone. A drawing of Zeus on a krater and a young hunter on a krater show the man’s chiton. The Ionic chiton is illustrated by the statue of a goddess. Metal buttons to represent the sleeve fastenings were inserted in the marble.

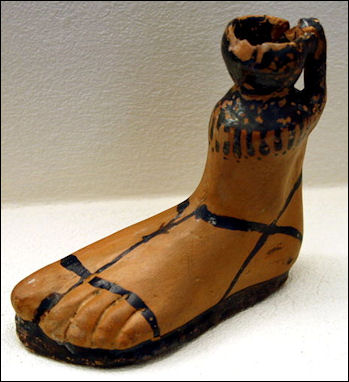

Ancient Greek Footwear

Shoes were of two principal types: sandals with straps, and high shoes or boots for hunting and traveling. The Greeks valued finely made shoes, and dandies sometimes invented new fashions which were called by their names, as “Alkibiades shoes.” A terracotta foot from Cyprus wearing a sandal is shown on the left. On a krater Hermes wears high laced boots with a tongue rising above the laces, and a stamnos shows the hunter Eos in boots. The bronze statuette of the philosopher Hermarchos wears sandals which are worked out in detail, and an idea of the thickness of the soles may be gained from those worn by the woman on a stele. The number and arrangement of the straps which held the sandal in place were various and they were sometimes broad enough to form what was practically a shoe. Women wore sandals or low shoes. Black was the usual color for foot-coverings, but gay colors were worn by women and young men. The warm climate and custom permitted people often to dispense with shoes in the house, and working-men went barefoot. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Sandals were the primary form of footwear in ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece and Rome. Wealthy Greeks wore sandals decorated with jewels and gold. Roman developed sandals with thicker soles, leather sides and laced insteps. Footwear was mainly the rich. The poor mostly went barefoot. Both women and men wore sandals, slippers, soft shoes, or boots, although at home they usually went barefoot. In the 5th century B.C. actors wore platform shoes not unlike those worn by modern glam rockers. Women in ancient Greece and Rome wore thick-soled sandals. Early Greek actors and comedians wore a light pull-on shoes or sykhos. Developed versions of these were made of leather and wood and had a division between the first and second toes.

At home, and in summer, men as a rule went barefoot; artisans and other members of the lower classes and slaves did so out-of-doors also, as well as people who desired to harden their bodies, like Socrates, or those who perhaps only affected an ascetic mode of life, like some of the Cynic philosophers. At Sparta, where the State took cognisance of the dress and food of the citizens, young men were actually forbidden to wear shoes, and many adhered to this habit even in old age, as, for instance, Agesilaus, who, even as an old man, used to go without shoes and chiton, dressed only in his cloak. Still, it was unusual for men to go out of doors in winter barefoot, as Socrates is said to have done during his campaign in Macedonia. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Besides sandals and boots, there were a great number of transition stages, so that it is sometimes impossible to say to which of the two classes some kinds belonged. Sandals, which were probably the oldest kind, and in Homer apparently the only one, were worn by men and women alike, though far more commonly by the latter. They consisted of a sole made of several thicknesses of strong leather, with sometimes a layer of cork; to this straps were fastened, which passed across the foot and held them firm. For this purpose a pair of straps passing over the instep and heel were often sufficient, and these were either tied or fastened in such a way that another strap, passing between the first and second toes, was connected with the other two, which were fastened to the edge of the sole and buckled on the instep, the buckle usually having the shape of a heart or a leaf. But these straps were often more numerous, and so complicated as to cover almost the whole foot, and thus resemble a perforated shoe. Sometimes they were continued as far as the ankle, or even the shins, but this is only the case in men’s dress. Costly and brightly-coloured leather, with gilt and other ornaments, made this footgear, which was naturally simple, both ornamental and expensive.

Ancient Greek Boots

The boots were something like ours; they covered the whole foot, and were laced or buttoned in front, over the instep, or at the side. In the older period men’s boots generally went above the ankle, and at the front edge had a more or less pointed tongue bent forward. Afterwards, low shoes, generally stopping short of the ankle, were the rule, especially for women, if they did not wear sandals. They are usually pointed at the toes, and old Spartan reliefs even represent shoes with points in front as part of female dress. Huntsmen, countrymen, and the like, wore high boots reaching to the shins, laced or buttoned in front. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

footwear vase

These generally had broad toes and thick soles, but like the ordinary shoes they had no heels. A common decoration of such boots were broad zigzag lappets of leather, falling down from the upper edge. Between sandals and boots we find various forms of low shoes, in which the foot is partly covered with leather and partly with straps. Thus there was a kind of slipper covering the upper part of the foot in front, while the back was covered with straps, and another kind which left the toes quite free and covered the rest of the foot. Probably the crepida, which only originated in the Alexandrine period, but then became very common, belonged to this class, and was a shoe with low leather sides, from which straps passed across the foot. Other kinds of shoes we know only by their antique names. Thus there was an elegant kind worn by guests invited to dinner; and a coarser kind worn chiefly by peasants made of rough leather, and probably not on a block, but roughly sewn together by the country people themselves. The material used was, as a rule, leather, but occasionally felt. They were mostly black; but we also find coloured shoes mentioned, especially for women, and sometimes see them represented on polychrome vases.

The number of names for footgear used by the ancient writers is very large, and we may thence conclude that the fashion changed frequently. Thus in Greece there were shoes of the Persian fashion. At Athens they wore Laconian shoes; Amyclaean, Sicyonian, Rhodian shoes, and others which are also mentioned, probably refer more to the shape than to the origin. There were also shoes called after celebrated men, who probably made use of them, such as Alcibiades shoes, Iphicrates shoes, etc.; but we cannot illustrate all these from works of art, in spite of the rich variety supplied by them. They also distinguished between shoes which, like our slippers, could be worn on either foot, and those which were made on particular lasts for the right and left foot. The latter were regarded as more elegant, for they laid great stress on having shoes well-fitting and not too wide. They said of people who wore too comfortable shoes that they “swam about” in them. It was a mark of poverty or avarice to wear patched boots, and heavy nailed shoes were only worn by soldiers or country people, and for others were regarded as a mark of rusticity.

Socks, Gloves, Canes and Sunshades in Ancient Greece

Stockings were generally not known in antiquity, but sometimes in extreme cold it was the custom to wrap fur or felt round the legs. Thus, in Homer, old Laertes, when doing rough work in his garden wears gaiters of neat’s leather, and also gloves to protect himself against the thorns. As a rule, the latter were also unknown; only actors wore something of the kind, but their object was, by apparent lengthening of the arms, to harmonise them with the artificial increase in height. As early as 600 B.C. Greek women wore socklike slippers called “ sykhos”, the source of the word sock. Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The stick belonged to the ordinary equipment of a man. Old people walked with the help of a heavy knotted stick, or leant on it as they stood, like the Athenian citizens on the Parthenon frieze; and young people also used them. They seem always to have used natural sticks; but the Laconian canes, with curved handles, were considered specially convenient, and were used at Athens by those who liked to imitate Spartan manners and customs. In the fourth century the use of sticks seems to have become less common. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

For protection against the sun women often used sunshades, which were made to fold up like ours. Such sunshades are common on old monuments, but, as a rule, ladies did not carry them themselves, but were accompanied by a slave, who performed this office for them. The sunshades were usually round, but there are also examples of a fan-shaped kind, which enabled the servant who walked behind to hold the sunshade by its long handle comfortably over her mistress without going too near her. Sometimes we even see men on vase pictures with sunshades. This, however, was regarded as effeminate luxury.

Ancient Greek Hats

Man wearing a petaso on a coin from Macedonia, around 400 BC

Head-coverings were generally worn only by travelers, riders, or working-men. A hat with a wide brim, called “petasos,” was the usual traveler’s head-gear. It was made in a variety of shapes, the brim being sometimes broader at back and front, sometimes at the sides. Another form had a circular brim which turned up. This may be seen on three terracotta statuettes. A cap, called “pilos,” was worn by smiths, sailors, and working-men in general. Some head-coverings which may be either caps or small hats with rolled brims, are represented in several terracotta statuettes of boys.Women wore the petasos for traveling, and they also used a kind of sun-hat, called “tholia,” with a pointed crown and broad brim, made of straw and fastened by a ribbon. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

The first known hats with brims were worn by ancient Greeks in the fifth century B.C. The broad rimmed “ pelasus” of ancient Greece is considered by some scholars to be the world's first hat. It was worn while traveling for protection from the weather. They had chin straps that allowed them to hang down on the back when not needed. Greek men occasionally wore a broad-brimmed hat (petasos).

Women, who were seen out of doors much seldomer than men, had even less need for head-coverings. Especially in the oldest period, where scarves covering the greater part of the hair were in fashion, they probably contented themselves with drawing the himation over their heads when they went out. This was often done in later periods also, as we see in terra-cotta figures; it even at that time women in the country, or travelling, often wore a petasos similar to that of the men, though with a narrower brim. A graceful Sicilian terra-cotta, shows a lady wearing one of these, and it is very becoming to the face. On the other hand, after the Alexandrine period, the tholia is very common. This is a light straw hat, with a pointed crown and broad brim, fastened by a ribbon and balanced on the head — no doubt very convenient, since the broad brim protected the wearer from the rays of the sun, but by no means becoming. Terra-cotta figures from Tanagra give numerous examples of this hat, which was evidently very common at the time, and is also mentioned by writers. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Ancient Greek Jewelry

By the 5th century B.C., Greek craftsmen had raised jewelry-making to a fine art. Greek jewelry and ornaments included gold jewelry, diadems, beads, and intricately carved sealing stones. The Egyptians and Assyrians used enamel bricks to decorate their buildings. The Greeks and Romans were masters of using enamels to make jewelry.

Jewelry in use included necklaces and bracelets, rings for the ears and fingers, and pins for the hair and clothes. The Doric chiton originally required two very large pins, which were inserted with the points upwards, but they went out of use in the sixth century when the Ionic chiton came into fashion and were not worn with the later Doric chiton. The fibula or safety-pin was used throughout the Greek and Roman world. The fibula was sometimes worn in a head-band. Greek jewelry of the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. was frequently of great beauty. Precious stones were used but seldom until the Hellenistic period, but the excellence of Greek workmanship has rarely been equalled by other craftsmen. The Greek gentleman permitted himself only a handsome ring which was useful as a seal, and the artistic value of these engraved seal rings of gold or of gold set with a semi-precious stone has made them favorites with collectors for many centuries.[Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Some of the oldest known rings were used as signets by rulers, public officials and traders to authorize documents with a stamp. Signatures were not used until late in history. Most ancient rings were made of steatite (soapstone) or medals such as bronze, silver or gold. Few were adorned with precious stones. Those that were contained amethyst, coral or lapis lazuli. The Greeks believed that coral protected sailors for storms and amethyst had the power to keep people from getting drunk.

golden diadem from "Priam's Treasure"

Collete amd Seán Hemingway wrote: “When Alexander the Great conquered the Persian empire in 331 B.C., his domain extended from Greece to Asia Minor, Egypt, the Near East, and India. This unprecedented contact with distant cultures not only spread Greek styles across the known world, but also exposed Greek art and artists to new and exotic influences. Significant innovations in Greek jewelry can be traced even earlier to the time of Philip II of Macedonia (r. 359–336 B.C.), father of Alexander the Great. An increasingly affluent society demanded luxurious objects, especially gold jewelry. With technical virtuosity, Greek artists executed sumptuously ornate designs, such as the beechnut pendant, the acanthus leaf, and the Herakles knot (1999.209). [Source:Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

“After Alexander conquered the Persian empire and seized its fantastically rich treasures in Babylon, vast quantities of gold passed into circulation. The market for fashionable gold jewelry exploded. Even after the reign of Alexander, his successors for centuries supported flourishing industries of artists and craftsmen, the most important of whom were associated with the Hellenistic royal courts. \^/

“A wide variety of jewelry types were produced in the Hellenistic period-earrings, necklaces, pendants, pins, bracelets, armbands, thigh bands, finger rings, wreaths, diadems, and other elaborate hair ornaments. Bracelets were often worn in pairs according to Persian fashion. And jewelry was frequently produced in matched sets. Many pieces were inlaid with pearls and dazzling gems or semiprecious stones-emeralds, garnets, carnelians, banded agates, sardonyx, chalcedony, and rock crystal. Artists also incorporated colorful enamel inlays that dramatically contrasted with their intricate gold settings. Elaborate subsidiary ornamentation drew plant and animal motifs, or the relation between adornment and the goddess, Aphrodite, and her son, Eros. Airborne winged figures, such as Eros, Nike, and the eagle of Zeus carrying Ganymede up to Mount Olympus, were popular designs for earrings. \^/

“In Hellenistic times, jewelry often passed from generation to generation as family heirlooms. And occasionally, it was dedicated at sanctuaries as an offering to the gods. There are records of headdresses, necklaces, bracelets, rings, brooches, and pins in temple and treasury inventories, as, for example, at Delos. Hoards of Hellenistic jewelry that were buried for safekeeping in antiquity have also come to light. Some of the best-preserved examples, however, come from tombs where jewelry was usually placed on the body of the deceased. Some of these pieces were made specifically for interment; most, however, were worn during life. In the early Hellenistic period, wealthy Macedonians buried their dead with elaborate gold jewelry. However, by late Hellenistic times, rich burial goods were less common. This modification most likely signals a decrease in disposable wealth and, perhaps, a change in burial customs.” \^/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024