Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

FOOD IN ANCIENT GREECE

fish plate Foods consumed in ancient Greece included vegetables, legumes, fruits, meat and fish. Meats were roasted on spits, cooked in ovens, and boiled. Evidence of thin phyllo dough has been dated to the 4th century B.C. Food was sweetened with honey or products made from naturally sweet grapes. Wine, cereals, and olives formed the cornerstone of traditional Greek agriculture and diet.

The Greco-Romans ate porridge, honeycombs, puddings, irises, and lamb. Ancient people largely ate with their hands. Sometimes they used knives and spoons. Athenians reportedly didn't have breakfast but ate a single meal each day of porridge.

The oldest known pies were made in the 5th century B.C. Greece. Known as “ artocreas” , they were hash meat pies with only a bottom crust. Top crusts and fruit and sweet fillings were developed by the Romans. One of the most popular pies, “ placenta” , had a wheat-rye flour crust and had a filling made of honey, spices and sheep milk cheese. One of the greatest delicacy was foie gras made by force feeding figs to enlarge the goose’s liver. The Roman are sometimes credited with invented foie gras but the Greeks also ate it. In 1st century A.D. the Roman Emperor Nero ate desserts made from snow brought in from the mountains.

Almonds are one of the world's oldest cultivated crops. The ancient Mesopatamians used almond oil as a body moisturizer, perfume and hair conditioner. Almonds have been in the found in Minoan place in Knossos and were a favorite dessert food of the Greeks. They and pistachios are the only two nuts mentioned in the Bible.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece, Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Classical Cookbook” by Andrew Dalby and Sally Grainger (2012) Amazon.com;

"The Deipnosophists" (Banquet of the Learned) Vol. 1 by Naucratis Athenaeus, written about A.D. 200, Amazon.com;

“Plant Foods of Greece: A Culinary Journey to the Neolithic and Bronze Ages” by Soultana Maria Valamoti (2023) Amazon.com;

“Food and Drink in Antiquity: A Sourcebook: Readings from the Graeco-Roman World” (Bloomsbury Sources in Ancient History) by John F. Donahue (2015) Amazon.com;

“Courtesans & Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens” by James Davidson (1997) Amazon.com;

“Intoxication in the Ancient Greek and Roman World” by Alan Sumler (2023) Amazon.com;

“Famine and Food Supply in the Graeco-Roman World: Responses to Risk and Crisis”

by Peter Garnsey (1988) Amazon.com;

“Meals and Recipes from Ancient Greece” (J. Paul Getty Museum) by Eugenia Salza Prina Ricotti (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Cuisine of Ancient Greece: Ancient Recipes Revived”, featuring illustrations for every recipe, by Elena Winterbach (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Boastful Chef: The Discourse of Food in Ancient Greek Comedy” by John Wilkins | (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Early Neolithic in Greece: The First Farming Communities in Europe (Cambridge World Archaeology) by Catherine Perlès (Author), Gerard Monthel (Illustrator) Amazon.com;

“24 Hours in Ancient Athens: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Philip Matyszak (2019) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks” (The Greenwood Press Daily Life Through History Series) by Robert Garland (2008), Amazon.com;

“The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” (Classic Reprint) by Alice Zimmern (1855-1939) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks: Life and Customs” by E. Guhl and W. Koner (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Life of the Ancient Greeks, With Special Reference to Athens”

by Charles Burton (1868-1962) Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Life in Ancient Greece” by Leslie Adkins and Roy Adkins (1998) Amazon.com;

Grains in Ancient Greece

Bread and porridge were staples. The kinds of grain chiefly used were wheat and barley, as well as spelt; rye was not cultivated in Greece, and rye bread was regarded as food for barbarians. Bread was made chiefly of wheat, and was white or brown, according to the greater or less addition of bran and the finer quality of the flour. But the common people did not eat much wheaten bread; the chief daily food of the poorer people was a kind of barley cake, called maza, a sort of porridge, which was moistened and dissolved in water, and of which there were various kinds with different savoury additions. This porridge seems to have resembled the polenta still used in the south, but was probably not much eaten by the richer classes. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

woman grinding wheat

Barley grew well in Greece, but bread made with it was coarse and hard; Emmer, the wheat species that grew best in Greece also was not so good for making bread. . Broths, porridges, and mashes were made with grains. these. Athens and some other cities imported bread wheat from Sicily, North Africa, and the northern Black Sea coasts. Fine, mass-produced, industrially baked bread could be purchased at the Athenian market.In the “Odyssey,” Homer wrote: the "housekeeper brought in the bread" and "there is wheat and millet here and white barley, wide grown". Rice arrived in Egypt in the 4th century B.C. Around that time India was exporting it to Greece. [Source: Andrew Dalby, Encyclopedia of Food and Culture, Encyclopedia.com][Source: Ancientfoods, November 10, 2009]

Matthew Maher of the University of Western Ontario wrote: “The ancient Greeks used cereals not only as domesticate food, but also and more importantly, for bread. There is a significant amount of archaeological evidence to show the importance of cereals. At Knossos there are a number of indications that the ancient Greeks were heavy cereal eaters. In a small room later discovered to be a stable, archaeologists found stores of wheat, and it is interesting to note that it was not kept in a container. Vickery also claims that "wheat and barley certainly were the principle grains of the Aegean world". In the north, in Thessaly and Olynthus, samples of millet have been found as well as what might be rye. Moreover, German archaeologists working near Melos have discovered what they believe to be a model of a granary. [Source: Matthew Maher, University of Western Ontario, The Odyssey of Ancient Greek Diet, Totem: The University of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology, Volume 10, Issue 1, Article 3, June 19, 2011]

“The cereals used in ancient Greece are a reflection of the variable Greek climate and soil quality; for example, barley is tolerant to poorer soils and a range of climactic conditions and was, therefore, probably grown in Greece; while the more intolerant wheat was most likely imported. Bread was a staple commodity to the ancient Greeks. Archaeological discoveries of certain pottery covers suggest that they had been used in ovens. Bread could be placed on a slab of stone or pottery ware, covered with a lid of the sort referred to, and placed in an oven or over coals. There is an ongoing argument to whether these ovens were known in Homeric times because mention of them is absent in his work. According to archaeological and historical data, Garnsey (1999) believes that over the years barley lost ground to wheat, husked grains lost ground to naked grains, and eventually bread was preferred over porridge. Nonetheless, it is clear that cereals played an important role in ancient Greek diet. “

Bread in Ancient Greece

baking bread Bread was the staple of the Greek diet. People often ate it for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Wheat and rye were grown domestically and imported from North Africa (fertile and rain-drenched in Greek and Roman times). After these grains were crushed in washing-machine-size mortars and baseball bat-size pestles they were baked into bread and boiled into a porridge-like gruel. The wheat used to make round loaves of bread in Greece today is a similar to wheat used 3,300 years ago in the Copper Age and in ancient Greek times.

Charles King wrote in his website “A History of Bread”: “The Greeks and Romans liked their bread white; colour was one of the main tests for quality at the time of Pliny (A.D. 70). Those who think the craze for white bread is a modern fad should note this. Pliny wrote: ‘The wheat of Cyprus is swarthy and produces a dark bread, for which reason it is generally mixed with the white wheat of Alexandria’.[Source: Charles King, “A History of Bread” botham.co.uk/bread|~|]

“Plato (c. 400 B.C.) pictured the ideal state where men lived to a healthy old age on wholemeal bread ground from a local wheat. Socrates, however, suggested that this proposal meant the whole population would be living on pig-food. In those days, there were certain mean bakers who kneaded the meal with sea-water to save the price of salt. Pliny did not approve of this. |~|

“In ancient Greece, keen rivalry existed between cities as to which produced the best bread. Athens claimed the laurel wreath, and the name of its greatest baker, Thearion, has been handed down through the ages in the writings of various authors. During the friendly rivalry between the towns, Lynceus sings the praises of Rhodian rolls. ‘The Athenians’, he says, ‘talk a great deal about their bread, which can be got in the market, but the Rhodians put loaves on the table which are not inferior to all of them. When our guests are given over to eating and are satisfied, a most agreeable dish is produced called the “hearth loaf”, which is made of sweet things and compounded so as to be very soft, and it is made up with such an admirable harmony of all the ingredients as to have a most excellent effect, so that often a man who is drunk becomes sober again, and in the same way, a man who has just eaten is made hungry by eating of it.’ |~| “The island of Cyprus had a reputation for good bread. Another old writer, Eubulus, says, “Tis a hard thing, beholding Cyprian loaves, to ride carelessly by, for like a magnet, they do attract the hungry passengers.’”

Fruits in Ancient Greece

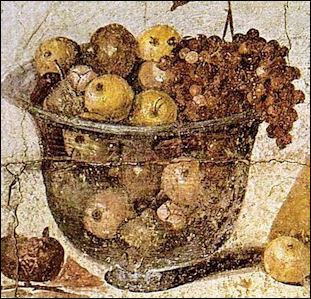

The Greco-Romans grew olives, tangerines, oranges and lemons often in poor soils.They ate figs, grapes, pears, and apples. Lemons, apricots and cherries were introduced to Rome around the A.D. 1st century. In the “Odyssey,” Homer wrote: "pear trees and pomegranate trees and apple trees "and "rows of greens, all kinds, and these are lush."

fruit in Pompeii fresco The fruits named in The Odyssey including apples, pears, grapes, pomegranates and figs. Grapes, dates, plums and figs were usually dried for preservation because they are better adapted to this process than apples or pears. Grapes were commonly made into wine. Other fruit juices were consumed. Matthew Maher of the University of Western Ontario wrote: Among vegetables, the ancient Greeks made the distinction between root vegetables and leafy greens and it appears that onions and garlic were the most popular. Herbs and spices were also present, and were not only used for food preparation, but were also often used for medicinal purposes. “At the ancient site of Dimini, there is a deposit that yielded the remains of wild pears and a large quantity of figs. Similarly, a site in Olynthus also yielded a significant quantity of figs. The presence of grapes (for wine or other) has been identified in Tiryns and Sparta. [Source: Matthew Maher, University of Western Ontario, The Odyssey of Ancient Greek Diet, Totem: The University of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology, Volume 10, Issue 1, Article 3, June 19, 2011]

“There exists a portrait of a priestess from Thera in which it appears that she is holding a vessel bearing fruit of some sort (grapes or berries). Additionally, a painting from Andriuolo dated 350 B.C. shows a woman carrying an offering that contains pomegranates. Ultimately it is easy to assume that the presence of the fruits and vegetables in the archaeological record is proof that the Greeks consumed them but this would be a precarious assumption. Only through careful excavation, taking into account the context of the food and through cross-referencing with art and literature can it be said with any degree of certainty that these fruits and vegetables were actually eaten."

Apples were mentioned in the Bible, Greek myths and the Viking sagas. The earliest apples were versions of crab apples. Pictures of apples have been found in caves used by prehistoric men. All trees which produce eating apples are believed to originate from the “Malu sieversii “ tree, which grows in the high altitude forests of Kazakhstan. Almaty, the capital of Kazakhstan, means “father of apples.” Apple tree orchards are found in and around Almaty. “Aport” is a famous variety of apple with links to ancient apples. [Source: Natural History, October 2001]

Scientists believe that “Malu sieversii” was hybridized with crab apples native to Central Asia. Most likely these hybrids not “Malu sieversii “ itself became the ancestors of the apples that people eat today. By the 3rd millennium B.C. eating apples were being cultivated over a wide area around the Tien Shan. By the 3rd millennium B.C. eating apples were common place around the Mediterranean. The Romans spread apple cultivation throughout their empire.

strawberries in Pompeii fresco Melons are one the earliest crops. Native to Iran, Turkey and western Asia, they are depicted in an Egyptian tomb painting dated to 2400 B.C. Greek documents from the 3rd century B.C. refer to them. Pliny the Elder described them in the 1st century A.D. Watermelon originated in Africa. Domesticated watermelon seeds dated to 4000 B.C. were found in the 1980s in southern Libya. Dorian Fuller of University College London told the New York Times, “The wild watermelon is a horrible, dry little gourd that grows in wadis of the northern savannahs but it has seeds you can roast up and eat.” The watermelon we eat was not developed until Roman times.

Pomegranates are ancient fruit. They are mentioned in the Bible, the Koran and the “ Odyssey” . According to one of the most famous Greek legends, Persephone was condemned to the underworld for eating a seed from a pomegranate. The Assyrians made necklaces of gold pomegranates. Pomegranates are thought have originated in Southeast Asia. They were found in much of the ancient world and are thought to have introduced to several places by the Phoenicians. The ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans used the fruit in their medicines.

Figs have been around since ancient times, when they were associated with magic and medicine. The Egyptians buried entire basketfuls with dead and valued them as a digestive aid. The Greeks called them “the most useful of all the fruits which grows on trees.” In the Middle Age, fig syrup was a popular sweetener.

Vegetables in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greeks ate green vegetables and salads, asparagus, radishes, mushrooms, lentils, peas, lupins, etc. These leguminous vegetables supplied nourishing fare for poor people, and were therefore sold by street cooks hot from the fire, at a low price. The Greco-Romans grew cabbage, leeks, and turnips. Cucumbers were known in ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome. They originated in the foothills of the Himalayas in northern India, where they have been cultivated for more than 3,000 years.

Matthew Maher of the University of Western Ontario wrote: ““Vegetable remains are much more abundant in the archaeological record than are fruits. On the mainland, the use of leguminous vegetables is proved to go back centuries before the onset of the classical period. Excavations near Sedes have produced jars containing these dried leguminous vegetables, specifically peas and beans. These and other similar vegetables were probably raised in the household gardens as they are grown today. Of the garden vegetables, only the legumes listed above could survive, so for the other types of vegetables we must rely on other forms of evidence. In a fresco found in Praeneste, there is an image of a vegetable garden in front of a house. [Source: Matthew Maher, University of Western Ontario, The Odyssey of Ancient Greek Diet, Totem: The University of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology, Volume 10, Issue 1, Article 3, June 19, 2011]

Cabbage is the world's most widely consumed vegetable and one of the first to be harvested. Native to the Mediterranean, it was eaten by Achilles in the “Iliad” and is believed to have introduced it to Europe and other parts of the world by the Romans. Asparagus was a favorite of the Romans. It was used mostly as a medicine in the Middle Ages before it became a popular food in the 17th century.

We find even in antiquity the fondness for onions and garlic still shown by southern nations, and these were eaten raw with bread. Besides salt, pepper, and vinegar, various spices were used to flavour the dishes, such as sesame, coriander, caraway, mustard, etc., and also silphium, which was much sought after because it served as a birth control method, but very expensive, and was imported from Cyrene, but could no longer be obtained at the beginning of the Christian era. Olive oil was used for cooking. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Onions originated in Egypt. Egyptians believed that onions symbolized the many-layered universe. They swore oaths on onions like a modern-time Bible. Radishes were cultivated by the ancient Egyptians at least 4,000 years ago. They were eaten with onions, and garlic by workers. Egyptians believed that radishes were aphrodisiacs. Leeks were also eaten in ancient Egypt.Ovid wrote that radishes were aphrodisiacs. Martial said onions were. In a popular epigram he wrote, "If you wife is old and your member is exhausted, eat onions in plenty."

Grapes, See Wine

Olives and Olive Oil in Ancient Greece

ancient olive tree in Pelion, Greece

Olives and olive oil were staples in ancient Greece and Rome. Olives were used as food. fuel and a trade commodity. Sophocles called olives "our sweet silvered wet nurse.” Olives were valued more as a source of fuel for oil lamps than as a food. They were also used to make soap. Olives were regarded as so precious that killing an olive tree was sometimes punished by death. In the “Odyssey,” Homer wrote: "oozes the limpid olive' oil" and "the flourishing olive".

Olives and olive oil have been staples of the Mediterranean diet for millennia. Their consumption is ancient Greece and Rome has been well documented. Italian archaeologists discovered that some of the world’s oldest perfumes, made in Cyprus, were olive oil based. The commodity was also used to fire copper furnaces and light lamps.

Olives were very important to the ancient Greeks. Olive production is best when there is a dry season for the olives to develop their oil content; a cool winter for the trees to rest; a climate with no frost; and elevations lower than 800 meters — conditions that exist in much of Greece. The cultivation of olive trees, and the use of olive oil dates back to the early part of the Bronze Age. Archaeological evidence of ancient olive cultivation includes traces of ancient orchards, olive mills and presses, and lots of amphorae used to transport and store oil. [Source: Matthew Maher, University of Western Ontario, The Odyssey of Ancient Greek Diet, Totem: The University of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology, Volume 10, Issue 1, Article 3, June 19, 2011]

Matthew Maher of the University of Western Ontario wrote: “ On the island of Naxos, the actual remains of olive oil were found in a jug discovered in a tomb. Interestingly, two lamps were found alongside the oil leaving archaeologists to wrestle with the idea that the oil was actually fuel. The discovery of great quantities of storage jars leads us to believe that the oil was probably a Greek export. It appears that the olives themselves were prepared for eating while the oil was used for cooking, salad oil, and applied to the skin for hygienic and cultural reasons.

“Olives and olive oil are represented in the art of the ancient Greeks. In Cretan art, olive trees (at fIrst questionable) are now being identifIed with confIdence due to the quantity of examples. One such example is found on a painted ceiling block entitled, The Diver, dated to 480 B.C., shows two distinct representations of olive trees. Because of the extensive archaeological evidence, it can be said with a fair deal of certainty that olives already existed for centuries prior to the classical period. The olive tree was Athena's gift to the Athenians after she defeated Poseidon for possession of Athens. It therefore represented the strength, peace, and continuity of the Greek state. Although it is of great nutritional importance, its cultural significance must not be overlooked.

A large number of olive stones found in a 2,400-year-old ancient shipwreck appear to indicate that olives were one of the main components of the diet of sailors in the ancient world, researchers at Cyprus’s antiquities department said. The shipwreck, discovered in deep waters off Cyprus’s southern coast, was of a ship dated to around 400 B.C. and carried mainly wine amphorae from the Aegean island of Chios and other north Aegean islands, Excavation which started in November 2007 determined that the ship was a merchant vessel of the late classical period. [Source: by Michele Kambas, Reuters, August 2010]

See Separate Article OLIVES: OIL, HISTORY, PRODUCTION AND SCAMS factsanddetails.com

Fish in Ancient Greece

Fish was the main source of protein. Fish were often eaten in fish cakes. Raw oysters were considered a delicacy. In Thebes. archaeologists have discovered small amounts of fish vertebra. These vertebrae represent a rare find because, to the ancient Greeks, fish was more of a delicacy than a regular part of the diet.

Andrew Dalby wrote in the Encyclopedia of Food and Culture: In Athens and many other Greek cities, fish was available at the market — expensive, as fine fish still is in Greece, but very fresh. Europe's first gourmet writer, Archestratus (c.350 B.C.), wrote extensively on the types of fish that should be sought in specific cities, during which season, at what price, and the manner in which it should be cooked. "The bonito, in autumn when the Pleiades set, you can prepare in any way you please. . . . But here is the very best way for you to deal with this fish. You need fig leaves and oregano (not very much), no cheese, no nonsense. Just wrap it up nicely in fig leaves fastened with string, then hide it under hot ashes and keep a watch on the time: don't overcook it. Get it from Byzantium, if you want it to be good. . . ." [Source: Andrew Dalby, Encyclopedia of Food and Culture, Encyclopedia.com]

A special delicacy was eels, from Lake Copais, which are often mentioned, and were favorites with all the Athenian gourmets. Otherwise, sea fish was preferred to fresh-water fish, and there seems no end to the various kinds mentioned, which were also prepared in many different ways. The inexhaustible wealth of the neighbouring sea permitted even the poor people to have fish in plenty; in particular, the delicate sardines, which were caught in the harbour of Phalerum, and which were cheap and also quickly prepared, formed an important article of food for the Athenians. There were also great quantities of salt and smoked fish, which were prepared in the large smoking establishments of the Black Sea and on the coast of Spain, and brought by traders to Greece. The salted tunnies, herrings, etc., were excellent and also cheap, and therefore very common as food for the people. In the houses of the richer classes the finer kinds were also used — various sorts of fish sauces, caviar, oysters, turtles, etc., which added to the variety of the bills of fare, and could satisfy even the daintiest palates. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Meat in Ancient Greece

For most Greeks meat was expensive and in short supply and rarely eaten. Cattle was not easy to raise in mountainous Greece and the pastures were best suited for sheep and goats. In many cases, animals were simply killed; they needed to be sacrificed to a god first. Eating meat was closely associated with ritual sacrifice although goats, pigs, sheep and cattle had all been domesticated by this time. Meat was thus associated with festivals, celebrations, family events. and other special occasions. In the “Odyssey,” Homer wrote: "and sacrifIce our oxen and our sheep and our fat goats" and "where his herds of swine were penned in sacrificed them." The sacrificial butcher-priest, the mageiros, who was always male, served also as cook on these occasions; the art of cooking was named for this profession, mageirike techne (sacrificer's art).[Source: Andrew Dalby, Encyclopedia of Food and Culture, Encyclopedia.com]

The ancients were acquainted with various kinds of sausage; we find allusions to these even in Homer; they were also acquainted with the practice of adulterating them by introducing the flesh of dogs or asses. Sausages made by stuffing spiced meat into animal intestines were made by the Babylonians around 1500 B.C. The Greeks also ate them and the Romans called hem “salsus” , the source of the word sausage. In the “ Odyssey” , Homer wrote "when a man beside a great fire has filled a sausage with fat and blood and turns it this way and that and is very eager to get it quickly roasted."

In poultry, they had fowls, ducks, geese, quails, and also wild birds, such as partridges and wood pigeons; the special favorites were thrushes, which were a very popular dainty in the poultry market, where dishonest poulterers blew the birds up in order to make them seem fatter and in better condition. A favorite kind of game was hare, which is very frequently mentioned; they even had a proverb, “To live in the midst of roast hare,” which means to be in a land of plenty. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Matthew Maher of the University of Western Ontario wrote: “Small domestic animals such as fowl were most likely prepared and cooked privately in the home while the larger animals, like the ones listed above, were most commonly cooked publicly and eaten at festivals. In The Odyssey, there are countless numbers of detailed descriptions of sacrifIcial arrangements, and they usually involved the blood letting of the animal followed by the consumption of the meat. Some of these sacrifIcial elements are hard to trace in the archaeological record, but the actual consumption itself is easier to distinguish. [Source: Matthew Maher, University of Western Ontario, The Odyssey of Ancient Greek Diet, Totem: The University of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology, Volume 10, Issue 1, Article 3, June 19, 2011]

“Bones of domestic animals have been found in such great quantities it is easy to assume that the ancient Greeks lived largely on meat, but this would be a mistake. Meat in the Aegean area was in relatively short supply. There is evidence that the Greeks domesticated and ate the flesh of sheep, goats, swine, and cattle. The three archaeological clues pointing to the fact they practiced domestication are "representations of men capturing cattle alive; evidence of the long-homed oxen being kept in captivity; and direct evidence of domestication".

An example of one of the numerous sites found that contain animal remains is Thebes. Here archaeologists have discovered the processed remains of sheep, swine, cattle, wild boars and rabbits. Other forms of archaeological evidence can be found by examining reliefs found on both walls and pottery. A beautiful fresco from Corinth dated 500 B.C. shows a procession approaching an altar with a sheep for sacrifIce. Another good example is the Dionysus amphora mentioned above, which also shows two maenads holding up a slaughtered hare to their wine god. Meat and other foods of animal origin in the Greek world were in relatively short supply and, therefore, were probably of minor importance in the diets of the population. Meat was never a staple to the ancient Greeks and although its dietary importance was relatively small, its cultural significance was much greater”

Milk and Cheese in Ancient Greece

Hellenistic era cow

The fish was often cooked with cheese. In the “Odyssey,” Homer wrote: "baskets were there, heavy with cheeses" and “he sat down and milked his sheep".

Matthew Maher of the University of Western Ontario wrote: “As mentioned earlier, the people of classical Greece kept sheep, goats, and cattle. It is certain that the goats and sheep yielded milk, and it is probable that besides being drunk as sweet or soured milk it was also used for making cheese. Certain seals have been found that have illustrations depicting milk jars but there is no direct evidence of the milk's source. Although it is likely that some cow's milk was used, the fact that there was a significantly larger quantity of goats, has lead archaeologists to believe that goat's milk was more common. Furthermore, because milk and cheese are perishable and not easily transported, it was probably not kept in a regular supply. [Source: Matthew Maher, University of Western Ontario, The Odyssey of Ancient Greek Diet, Totem: The University of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology, Volume 10, Issue 1, Article 3, June 19, 2011]

“German archaeologists discovered a late classic relief showing a peasant driving a goat to market with what appears to be a jar of milk and a sack of cheese. Moreover, there are countless reliefs showing the milking of sheep and goats. Because of the short life and the perishable nature of milk and cheese, it will be extremely difficult (if not impossible) to ever find hard evidence in the archaeological record. In this situation, like that of the fruits and vegetables, proof must be sought in other media like art and literature.”

Insects as Food in Ancient Greece

The Greeks ate insects. Aristotle wrote that he liked cicadas best when they were in the nymph stage, adding that “first males were better to eat, but after copulation the females, which are then full of white eggs.” Aristophanes (446-386 B.C.), the fames Greek dramatist, called grasshoppers “four winged fowl.” Professor Gene R. De Foliart wrote: “ In one of the earliest references to the eating of insects in Greece, Aristophanes, quotes poulterers who sell "four-winged" fowl on the market. According to Bodenheimer these four-winged fowl were grasshoppers which apparently were cheap and consumed by the poorer classes. Young shepherds in the fields also enjoyed eating them. [Source: “Human Use of Insects as a Food Resource”,Professor Gene R. De Foliart (1925-2013), Department of Entomology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2002]

While the lower-class Greeks ate locusts or grasshoppers, the upper-class Greeks apparently preferred cicadas. According to Aristotle (3rd Century B.C.), the most polished of the Greeks considered cicada nymphs the greatest of tid-bits. Aristotle hinted that they were not an uncommon food in Attica (Athens) and wrote: "The larva of the cicada on attaining full size in the ground becomes a nymph (tettigometra); then it tastes best, before the husk is broken [i.e., before the last moult] . . . . [Among the adults] at first the males are better to eat, but after copulation the females, which are then full of white eggs.”

In the 1st Century AD a statement by the Greek writer Plutarch indicates that many Greeks believed that cicadas should not be eaten: "Consider and see whether the swallow be not odious and impious . . . . , because it feeds upon flesh and kills and devours the cicadas, which are sacred and musical.”

Pliny the Elder, 1st Century AD Roman natural history author, mentions that cicadas are eaten in the East. Pliny also records that Roman epicures of his day highly esteemed the Cossus grub and fattened them for the table on flour and wine. There has been much confusion about the identity of the Cossus, which Pliny stated feeds in oak. Bodenheimer lists several species that have been put forward by various authors as the Cossus of Pliny, but credits Mulsant with settling the question, and concludes that almost certainly it was the larva of Cerambyx heros Linn. [Source: “Human Use of Insects as a Food Resource”,Professor Gene R. De Foliart (1925-2013), Department of Entomology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2002]

Cowan discussed the Cossus as follows: The Cossus of the Greeks and Romans, which, at the time of the greatest luxury among the latter, was introduced at the tables of the rich, was the larva, or grub, of a large beetle that lives in the stems of trees, particularly the oak; and was, most probably, the larva of the Stag-beetle, Lucanus cervus. On this subject, however, entomologists differ very widely . . . . But the larva of the Lucanus cervus, and perhaps also the Prionus coriarius, which are found in the oak as well as in other trees, may each have been eaten under this name, as their difference could not be discernible either to collectors or cooks. . . . Pliny tells us that the epicures, who looked upon these cossi as delicacies, even fed them with meal, in order to fatten them.

Athenaeus, about 200 AD, mentions cicadas as dainties in Greek banquets, being served to stimulate the appetite. Athenaeus' opinion should possibly carry extra weight as he was a Greek grammarian and rhetorician who wrote extensively on Greek contemporary life, including cookery.

Third Century AD Roman sophist naturalist and author Aelian sounds another discordant note regarding cicadas when he reports with discontent that he saw people selling small parcels of cicadas for food. Aelian also tells that the King of India served as dessert for his Greek guests a dish of roasted grubs from palm trees, which Holt believes to have been the palm weevil, Calandra palmarum. The locals considered these grubs a great delicacy, but the Greeks did not enjoy them.

First Chickens in the West

jungle fowl (chicken)

Some of the earliest evidence of chickens being consumed as food in the West comes from Maresha, an ancient, abandoned city in Israel that flourished in the Hellenistic period from 400 to 200 B.C.. “The site is located on a trade route between Jerusalem and Egypt,” says Lee Perry-Gal, a doctoral student in the department of archaeology at the University of Haifa. As a result, it was a meeting place of cultures, “like New York City,” she says. [Source: Daniel Charles, NPR, July 20, 2015]

Daniel Charles of NPR wrote: “The surprising thing was not that chickens lived here. There’s evidence that humans have kept chickens around for thousands of years, starting in Southeast Asia and China. But those older sites contained just a few scattered chicken bones. People were raising those chickens for cockfighting, or for special ceremonies. The birds apparently weren’t considered much of a food.

In Maresha, though, something changed. The site contained more than a thousand chicken bones. “They were very, very well-preserved,” says Perry-Gal, whose findings appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Perry-Gal could see knife marks on them from butchering. There were twice as many bones from female birds as male. These chickens apparently were being raised for their meat, not for cockfighting.

Perry-Gal says there could be a couple of reasons why the people of Maresha decided to eat chickens. Maybe, in the dry Mediterranean climate, people learned better how to raise large numbers of chickens in captivity. Maybe the chickens evolved, physically, and became more attractive as food. But Perry-Gal thinks that part of it must have been a shift in the way people thought about food. “This is a matter of culture,” she says. “You have to decide that you are eating chicken from now on.”

In the history of human cuisine, Maresha may mark a turning point. Barely a century later, the Romans starting spreading the chicken-eating habit across their empire. “From this point on, we see chicken everywhere in Europe,” Perry-Gal says. “We see a bigger and bigger percent of chicken. It’s like a new cellphone. We see it everywhere.”

See Separate Article: CHICKENS: THEIR HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS AND DOMESTICATION europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024