Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

ANCIENT GREEK WEDDINGS

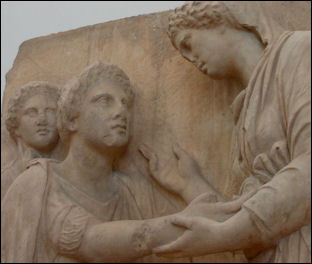

family scene on funerary stele It is likely that many ancient Greek brides and grooms never even met each other before their wedding day. Greek historian Ian Jenkins speculates that for some young brides the shock of being taken away from home and placed in a house with a complete stranger was "a frightening, even traumatic, experience." To symbolize the passing of her youth, on the day before her wedding, the bride sacrificed all of her toys to the virgin goddess Artemis and took a ritual bath with perfumed water from a vessel depicting a marriage scene and then swore fealty to Demeter, the goddess or agriculture and married women.| [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum,||]

On the wedding day itself, rich couples rode in a chariot to the groom's house, where the ceremony was held; poor couples were taken in an ox or mule cart. Before she was picked up the bride often pleaded with her mother to be hidden somewhere. When the couple arrived at the groom's house they were showered with dates, figs, nuts and small coins by the groom's family. After some verses were recited in a small ceremony, the couple was ushered into a bedroom where the marriage was consummated. It wasn't until the next day that the two families got together for a big wedding party. Presents, which were given only to the bride, were held in a trust so that if her husband died prematurely (not an uncommon occurrence) she would have a way of taking care of herself.||

Weddings usually took place in the winter, and a favorite time was the month Gamelion (the end of January and beginning of February), which hence received its name. Certain days regarded as auspicious were generally chosen, and the waning moon was specially avoided. It is curious, when we compare our own and the Roman customs, to note that, though the wedding received a religious character by sacrifices and other solemn ceremonies, it was not of itself regarded as a religious or legal act. The legality of the marriage depended on the engagement, and the religious consecration was not given by a priest (who took no part, as a rule, in the wedding ceremony), but by the marriage gods, who were invoked by prayer and sacrifice, more especially Zeus and Hera, Apollo, Artemis, and Peitho, the goddess of persuasion. We must now endeavour to form an idea of an Athenian wedding ceremony, as described by Greek writers. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

See Separate Articles: ANCIENT GREEK MARRIAGE: CONTRACTS, COUSINS AND DIVORCE europe.factsanddetails.com ; FAMILY LIFE IN ANCIENT GREECE: WIVES, ROLES, KIDS europe.factsanddetails.com ; LOVE IN ANCIENT GREECE: DATING, SPELLS, TABLETS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Marriage to Death: The Conflation of Wedding and Funeral Rituals in Greek Tragedy” (Princeton Legacy Library) by Rush Rehm (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Family in Greek History” by Cynthia B. Patterson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Family” by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges (1830-1889) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Houses and Households: Chronological, Regional, and Social Diversity”

by Bradley A. Ault and Lisa C. Nevett (2005) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Greece” by Susan Blundell (1995) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook” by Bonnie MacLachlan (2012) Amazon.com;

“Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from the Classical Past”

by Jenifer Neils , John H. Oakley , et al. (2003) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks” (The Greenwood Press Daily Life Through History Series) by Robert Garland (2008), Amazon.com;

“The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” (Classic Reprint) by Alice Zimmern (1855-1939) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks: Life and Customs” by E. Guhl and W. Koner (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Life of the Ancient Greeks, With Special Reference to Athens”

by Charles Burton (1868-1962) Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Life in Ancient Greece” by Leslie Adkins and Roy Adkins (1998) Amazon.com;

“Household Gods: Private Devotion in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Alexandra Sofroniew (2015) Amazon.com;

Ancient Greek Wedding Customs

Women in ancient Greece spent the day prior to marriage — known as proaulia — making offerings and sacrifices to gods, especially Artemis, the goddess of chastity and childbirth, says historian Emily Brand. One of the earliest recognized pre-wedding customs practiced by men took place in ancient Sparta, where soldiers would toast one another on the eve of their friend's wedding. [Source Isobel Whitcomb, Live Science July 18, 2020]

María José Noain wrote in National Geographic History: On the day of a wedding, female attendants would often prepare a purifying bath carrying water in a loutrophoros, an elongated vessel with two handles and a narrow neck typically decorated with marriage scenes. Archaeologists have uncovered loutrophoroi left as offerings in various temples, including in the Sanctuary of the Nymphe on the Acropolis in Athens.[Source María José Noain, National Geographic History, September 29, 2022]

Female attendants dressed and crowned brides in their father’s house, where the marriage ceremony would also take place. After the wedding, custody and protection of the bride was officially transferred from her father to the groom. A festive procession accompanied the newlyweds to their new home. The celebrations continued into the next day, when the bride received gifts from her family and friends.

On the marriage-vases we see the bride being dressed by her friends and servants, or receiving presents on the day after the wedding, the traditional occasion for the presentation of gifts. The usual presents seem to have been bands and ribbons for the hair, perfumes, jewelry, and pets, especially birds.[Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Greek brides wore veils. In Aphrodisias it was a common custom for women to prostitute themselves in the Temple of Aphrodite before they were married. The money they earned was donated to the goddess. Women who didn't want to go along with this could sacrifice their hair instead. Aphrodite was a metamorphosed form of the Babylonian fertility goddess, Ishtar, who Julius Caesar, Romulus and Remus, and the Trojan Aeneashave were all said to have descended from. [Source: Kenan T. Erim, National Geographic, October 1981 **]

In Sparta, the bride was usually kidnapped, her hair was cut short and she dressed as a man, and laid down on a pallet on the floor. "Then," Plutarch wrote, "the bride groom...slipped stealthily into the room where his bride lay, loosed her virgin's zone, and bore her in his arms to the marriage-bed. Then after spending a short time with her, he went away composedly to his usual quarters, there to sleep with the other men."||

The world's first known stag parties were held by the Spartans. At these parties Spartan grooms were given a feast by their friends and comrades the night before his wedding. There was no doubt singing, drinking and lewd jokes. The ritual marked the end of bachelorhood and the groom assured his comrades he would remain loyal to them and not leave them.

Wedding Rites in Ancient Greece

a kiss Among the ceremonies bearing a religious character which preceded the wedding, an important part was played by the bath. Both bride and bridegroom took a bath either on the morning of the wedding-day or the day before, for which the water was brought from a river or from some spring regarded as specially sacred, as at Athens the spring Callirhoe (or Enneacrunos), at Thebes the Ismenus; and this water had to be fetched by a boy who was some near relation; sometimes, however, we hear of maidens sent to fetch it. The bride also offered libations and gifts — as, for instance, her toys, locks of hair, and the like — to one of the marriage goddesses. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

More important was the sacrifice generally celebrated on the wedding-day, but we know few details about the mode of its performance. It was offered to the marriage deities mentioned above, either to all collectively or singly; the families of both bridegroom and bride took part in the ceremony. We do not know of any special directions as to the animals to be sacrificed; it appears to have been the custom to remove the gall of the victim, and not burn it with the rest of the inner parts, and this was supposed to indicate symbolically that all bitterness must be absent from marriage.

Most sacrifices connected with the slaughtering of animals were followed by a festive banquet, at which the flesh of the victims constituted the principal dish, and thus the wedding sacrifice also was followed by a feast, which was generally held at the house of the bride’s father. As this must, according to custom, have taken place in the afternoon, we may assume that the other wedding ceremonies had been performed in the morning.

Wedding Banquet in Ancient Greece

The wedding banquet was one of the few occasions when men and women dined together; this generally occurred only in most intimate family circles, but not when guests were present. The luxury of these wedding banquets seems to have increased so much that the State was at last obliged to limit the number of guests by law. Plato would not have allowed husband and wife to invite more than five friends and five relations each — that is, twenty in all — on any occasion, whether a wedding or otherwise; and a statute of the fourth century B.C. makes thirty the maximum limit for weddings, and instructs the officials who had charge of the women to see that this rule is not infringed; and they seem to have carried out their office so strictly that on these occasions they often entered the house, counted the guests, and turned out all who exceeded the legal number. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

At the banquet, as well as at the sacrifice which preceded it, the bride appeared in all her bridal adornments. Some female relation or friend who took the part of a modern bridesmaid undertook to deck the bride and anoint her with costly essences, and dress her in clothes of some fine, probably coloured, material, while special shoes, ribbons, and flowers in the hair were regarded as important, as well as the veil, which was the special mark of the bride, and covered the head, falling low down and partly covering the face.

The bridegroom, too, appeared in a festive white dress, which differed from his ordinary clothing chiefly by the fineness of material; he, too, wore a wreath, as did all the other guests at the banquet; but special flowers, supposed to be of fortunate omen, were worn by the bride and bridegroom. We do not hear of any special dishes supplied at weddings, but cakes, to which the Greeks assigned a symbolical connection with festive occasions, played an important part, and in particular cakes of sesame found a place at the wedding banquet. A special custom peculiar to Athens was for a boy, both of whose parents must be alive, to go round wreathed with hawthorn or acorns carrying a basket of cakes, singing, “I fled from misfortune, I found a better lot.”

Wedding Songs from Ancient Greece

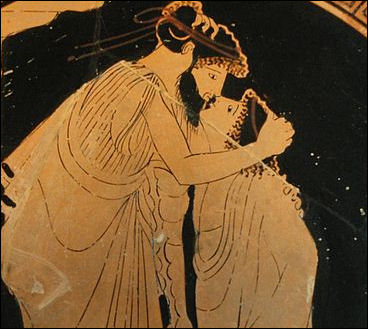

alabastron with a courtship scene

Aristophanes, “Wedding Song to Hymenaios” (c. 400 B.C.) found at the end of the Birds goes:

Zeus, that god sublime,

When the Fates in former time,

Matched him with the Queen of Heaven

At a solemn banquet given,

Such a feast was held above,

And the charming God of Love

Being present in command,

As a bridegroom took his stand

With the golden reins in hand,

Hymen, Hymen, Ho!

[Source: Mitchell Carroll, Greek Women, (Philadelphia: Rittenhouse Press, 1908), pp. 96-103, 166-175, 210-212, 224, 250, 256-260]

“Anacreon, The Morning Nuptial Chant", c. 400 B.C.

Aphrodite, queen of goddesses;

Love, powerful conqueror;

Hymen, source of life:

It is of you that I sing in my verses.

'Tis of you I chant, Love, Hymen, and Aphrodite.

Behold, young man, behold your wife!

Arise, O Straticlus, favored of Aphrodite,

Husband of Myrilla, admire your bride!

Her freshness, her grace, her charms,

Make her shine among all women.

The rose is queen of flowers;

Myrilla is a rose midst her companions.

May you see grow in your house a son like to you!

Wedding Procession in Ancient Greece

Among the ancient Greeks, a procession of the bride and groom to the bathhouse, led by flute players and torchbearers, was an integral part of the wedding ceremonial. A young male child carried a special jar for the bathing of the couple.

When the banquet was concluded, according to custom, by libation and prayers, and the night began to set in, the bride was conducted home to the house of the bridegroom. It was only among very poor people that the bride went on foot in this procession; if it was at all possible, she took her place between the bridegroom and the groomsman, who was a near relation or intimate friend of the bridegroom, in a carriage drawn by oxen or horses. All the other persons who took part in the procession — that is, all who had been at the banquet, and probably many others as well — went on foot behind the carriage to the sound of harps and flutes, while one went on in front as leader. The bride’s mother occupied the place of honour in the procession, carrying in her hand the bridal torches, kindled at the family hearth, and thus the bride took the sacred fire of her home to her new dwelling. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

On this account the ancients represented the god of Marriage, Hymen, with a torch as symbol. If other members of the procession also carried torches, that was only in accordance with the custom of using them when going out in the evening; it was only the torches of the bride’s mother that had any symbolical meaning. Meanwhile the bride’s attendants sang a bridal song, while the procession moved through the streets to the bridegroom’s house.

The bridegroom’s mother, also carrying torches, awaited the procession by the bridegroom’s door, which was festively decked with wreaths. A shower of all manner of sweetmeats was poured on the bridal pair, partly in jest and partly to symbolise the rich blessing invoked upon them; nor was the serious work forgotten which now awaited the young wife in her new position: a pestle for bruising the corn grains was hung up near the bridal chamber, to remind her of her duties as head of the household, and it was an ancient Athenian custom for the bride herself to carry some household implement in the procession, as, for instance, a sieve or a vessel for roasting. Another symbolical custom, supposed also to date from an ordinance of Solon, was for the bride, after her arrival in her new home, to eat a quince, which, like the pomegranate, was supposed to be a symbol of fruitfulness.

Epithalamium — Sung When Couple Enters the Bridal Chamber

An Epithalamium was a song or poem to celebrate a wedding. It often refers to the bedding of the bride and groom and were recited or sung outside bridal chamber (the thalamos in Greek) by young men and maidens, usually accompanied by soft music. The best Greek proponent of the epithalamium verse form was the poetess Sappho (said to be born at Mytilene in the island of Lesbos around 612 B.C.). She often commissioned to write marriage poems for aristocratic families. A surviving fragment of one of Sappho’s verses is: Bride, full of rosy love-desires; Bride, the most beautiful ornament of Aphrodite of Paphos, Go to your marriage-bed, Go to the marriage-couch whereon you shall play so gently and sweetly with your bridegroom; and may the evening star lead you willingly to that place, for there you will be astonished at the silverthroned Hera. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004]

Typically after wedding procession, the The bridegroom’s mother attended the bridal pair to the bridal chamber, where the richly-decked, flower-strewn marriage couch was prepared. When all the guests had gone away the bridegroom locked the door, and while the bride unveiled herself to him for the first time, the youths and maidens outside sang another song — either a few verses of the Hymenaeus or an Epithalamium, accompanied with praises of the married pair, and also doubtless by some jesting personal allusions.The Epithalamium of Helen, in Theocritus, begins thus: “Slumberest so soon, sweet bridegroom?

Art thou over-fond of sleep?

Or hast thou leaden-weighted limbs?

Or hadst thou drunk too deep

When thou didst fling thee to thy lair?

Betimes thou shouldst have sped,

If sleep were all thy purpose,

Unto thy bachelor’s bed,

And left her in her mother’s arms

To nestle and to play,

A girl among her girlish mates,

Till deep into the day:

For not alone for this night,

Nor for the next alone,

But through the days and through the years

Thou hast her for thine own.”

[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

And it ends thus:

“Sleep on, and love and longing

Breathe in each other’s breast;

But fail not, when the morn returns,

To rouse you from your rest:

With dawn shall we be stirring,

When, lifting high his fair

And feathered neck, the earliest bird

To clarion to the dawn is heard.

O God of brides and bridals,

Sing ‘Happy, happy pair!’”

Very often the young men, before setting out homewards, amused themselves by knocking and banging at the door of the bridal chamber, though a friend of the bridegroom’s kept watch there, ostensibly to prevent the maidens from going in to their married comrade. The last lines of the above-quoted epithalamium show that the chorus sometimes returned early next morning to greet the pair on their awakening.

Day After the Wedding in Ancient Greece

On the morning after the wedding, the newly-married pair received visits and congratulations from their relations and friends. The husband presented his young wife with gifts, and so also did the visitors, but this ceremony sometimes did not take place till the second day after the wedding; for a curious custom existed (only at Athens, however) for the husband on the day after the wedding to move into his father-in-law’s house, and there spend a night apart from his wife; she then sent him a new garment, whereupon he returned to her. With the wedding presents the dowry was often presented, along with various objects belonging to the trousseau, such as jars, ointments, sandals, toilette implements, etc. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The wedding festivities were then concluded by a banquet given either by the bridegroom’s father in his house or by the bridegroom himself; but it does not appear that there were any women present on this occasion. Still, this banquet was of a certain importance for the young wife; at Athens it was connected with her formal admission among the clansmen to whom the bride now belonged by her marriage. Every tribe (φυλή) at Athens was divided into three clans (φρáτραι), each of these into thirty households (γένη); the members of the clans examined into the purity of descent of citizens, and every new-born child had to be entered in their register. This ceremony gave a sort of official, or at any rate public, legitimation to the marriage.

Among the monuments which have been preserved to us, there are several which refer to marriage; but, as a rule, they adhere to a mythological form, and do not represent a real scene from daily life. Thus, for instance, we often see the bridal pair driving in a car, but those who attend them are the Marriage gods in person, especially Apollo and Artemis, and when the presentation of marriage gifts to the newly-wedded pair is represented, it is usually the celebrated couple, Peleus and Thetis, that we see depicted, while those who offer them the gifts are gods, such as Hephaestus and the Horae, etc. The vase painting also bears a mythological character, though it, no doubt, adheres very closely to the forms of reality. It represents the arrival of the bride at the bridegroom’s house. The latter stands leaning on a spear (which, however, must be an heroic attribute, and not customary at marriages in the historic period) before the door of his house. On the left comes the bride, who is recognised by the veil covering her head. She approaches with a hesitating step, and the bridesmaid attending her is pushing her gently forward with both hands, while the groomsman, who goes before her, holds her left hand. Apollo, with his laurel staff, and Artemis, with quiver and bow, are gazing sympathetically at the bride; in front of them a woman, either the match-maker or the bride’s mother, holds out both her arms to welcome the bridegroom.

Scene from the Kadmos Painter, an amphora dated to 425 BC, depicting w wedding scene on the left with a crowned bride surrounded by attendants who are preparing her for her wedding; Eros (Cupid), winged god of love, stands just behind; The scene on left shows a young man pursuing a woman while another woman flees

Wedding Customs in Different Places in Ancient Greece

Of course, marriage customs differed considerably in the various Greek states, as is proved by many allusions. Strangest of all seems the Laconian custom, which points clearly to marriage by capture; a custom of great antiquity, mentioned in many legends (as, for instance, that of the Dioscuri and the daughters of Leucippus). No mention is made here of a real marriage celebration; the bridegroom carried off his bride, who must, however, have previously been betrothed to him by her father, from her parents’ house, and in his own dwelling handed her over to the charge of some middle-aged woman, who was either a relation or an intimate friend. During his absence at the common dining table, to which all Spartan citizens and youths went every day, this woman cut off the bride’s hair, dressed her in male dress, with men’s shoes, and left her lying in the dark on some straw. Then, when the bridegroom returned, he unloosed the bride’s girdle and carried her in his arms to the bridal chamber. Curiously enough, the appearance of secrecy was kept up for some time longer; the young husband continued to live with the other young citizens, and only visited his wife occasionally in secret. Similar practices prevailed also at Crete. We do not, however, know how long these strange customs continued in the Doric states. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

In considering the position of women in relation to men and in the household, we must allow for the differences between the heroic and historic periods, and also between the Doric and the Ionic-Attic states. Of the Aeolian states we know very little. In the heroic period, as far as we can gather from the Homeric poems, women occupied an important position, in many respects equal to that of the men. Heroic times, like the rest of Greek antiquity, were only acquainted with monogamy; polygamy is an entirely Asian custom. Still, it was by no means unusual in olden times for princes and nobles to have a number of concubines, who were either slaves or female captives, besides their own lawful wives, who were sprung of noble family. In fact, the idea of conjugal fidelity held good only for the female portion of the population, while the men were absolutely free to act as they pleased. Undoubtedly there were cases in which husband and wife were so well suited together that the men resisted all temptations to infidelity; among these we may include Hector, Laertes, and Odysseus, in spite of the amours of this last with Circe and Calypso. Whenever we obtain a closer insight into the conditions of married life, as in the case of Hector and Andromache, Odysseus and Penelope, the impression received is a favorable one. There is even a vein of true affection perceptible, which is generally absent from ancient conceptions of marriage.

In the heroic age women were chiefly occupied with household management and female accomplishments, while they plied their tasks with their attendants in the women’s apartments; but their life was not one of such absolute retirement as that of the Asian harems. On some occasions they associated with men, and took part in their sacrifices and banquets; and though they never went out unattended, yet a good deal of liberty must have been allowed the young girls, to judge from the story of Nausicaa, who went down to the sea-shore to wash the clothes.

In the historic age, the Doric states bear the closest analogy to heroic times in their marriage customs. Here, too, we find the same undisguised assumption that marriage existed for the sake of rearing children; and, in fact, the laws of Lycurgus permitted a man to transfer his conjugal rights for a time to another, if his childlessness imperilled the existence of the family. In spite — or, perhaps, on account — of this custom, infidelity was very rare at Sparta, even among the men, and the institution of hetaerae never gained ground there. Concubinage, which was very common in the heroic age, fell into disuse during historic times, but, except at Sparta, it was really discontinued only in name.

The domestic relations between husband and wife more closely resembled our own at Sparta than in the Ionic-Attic states. Even at Sparta the household was the center around which the woman’s life revolved, but she was not degraded into a mere housekeeper; a Spartan addressed his wife as “Mistress” (δέσποινα), made her the partner of his interests, and consulted her about matters of importance. This seemed so strange to the other Greek states that they were inclined to regard the Spartan husbands as henpecked, which was by no means the case; but there is no doubt that Spartan history can boast of far more remarkable women and admirable mothers than Athenian. The strong patriotism of the Spartan women which triumphed over gentler feelings is sometimes a little unattractive to our modern sentiments, but, in any case, these women command our fullest respect. The position of women in the Ionic states bears a more Asian character, and here it is the wife who addresses the husband as “Master.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024