Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

POPULATION OF ANCIENT GREECE

Greece is broken up into four major regions: 1) Thrace, Macedonia, Thessaly, Epirus in the north; 2), central Greece, including Thessaly; 3) the Peloponnesus; and 4) and the Greek islands in the Aegean Sea to the east and the Ionian Sea in the west. The mountainous northern part of Greece is considered part of the Balkans. Thrace, formerly part of Turkey, and Macedonia are south of Bulgaria on the eastern Greek panhandle. Epirus is south of Albania.

During the Golden Age of Greece Athens was home to about 75,000 people and and between 200,000 and 250,000 lived in the surrounding countryside called "Attica." The city had an area of about 0.7 square miles.

When ancient Greece was at its height it was resource poor and overpopulated. The Greeks needed to colonize the Mediterranean to get resources. Half of the population in some city states were farmers who lived outside the city. By the 4th century B.C. it has been estimated that in all of ancient Greece there were only about 250,000 people. After the Peloponnesian wars and the plague the population city-state of Athens had been reduced by from around 80,000 to as a low as 21,000.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Demography and the Graeco-Roman World: New Insights and Approaches”

by Claire Holleran and April Pudsey (2011) Amazon.com;

“Population and Economy in Classical Athens” by Ben Akrigg (2019) Amazon.com;

“Abortion in the Ancient World” by Konstantinos Kapparis (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks and Greek Civilization” by Jacob Burckhardt (1902) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks” by H. Kitto (Penguin History) (Six books) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greece: From Prehistoric Times to Hellenistic Times” by Thomas R. Martin (1996) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral Journeys: The Peopling of Europe from the First Venturers to the Vikings” by Jean Manco (2016) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Ancient DNA and the European Neolithic: Relations and Descent” by Alasdair Whittle, Joshua Pollard (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Early Neolithic in Greece: The First Farming Communities in Europe (Cambridge World Archaeology) by Catherine Perlès (Author), Gerard Monthel (Illustrator) Amazon.com;

“A Social Archaeology of Households in Neolithic Greece: An Anthropological Approach” (Cambridge Studies in Archaeology) Stella G. Souvatzi Amazon.com;

“In Search of the Indo-Europeans” by J. P. Mallory (1991) Amazon.com;

“The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World” by David W. Anthony (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Way” by Edith Hamilton (1930) Amazon.com;

“Sailing Wine-Dark Sea: Why the Greeks Matter “ by Thomas Cahill, Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Mask of Apollo” by Mary Renault, (1966), Novel Amazon.com;

“The Last of the Wine” by Mary Renault (1956), Novel Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History” by Sarah B. Pomeroy (1998) Amazon.com;

“Creators, Conquerors, and Citizens: A History of Ancient Greece” by Robin Waterfield (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World: From the Archaic Age to the Arab Conquests” by G. E. M. de Ste. Croix (1981) Amazon.com;

Skin Color in the Ancient World

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: The notion of "whiteness" or "Blackness" as conceived today would have been alien to ancient people. "The ancients simply didn't care about it the way that modern and contemporary people do. It wasn't relevant to them and their worldview. They were more concerned about her being Egyptian, Macedonian, a woman etc.," Jane Draycott, a classics lecturer at the University of Glasgow's school of humanities, told Live Science. [Source:Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 9, 2023]

That doesn't mean some ancient people didn't notice differences across cultural groups, Draycott said. "The Romans commented on the white blonde and red-haired peoples in Northern Europe and the dark-skinned, 'woolly' haired people from Africa, and saw both groups as being different from themselves," Draycott said..

Romans would not have considered themselves to have white skin but rather brown or olive-toned skin, Draycott said. This can be inferred from the fact that the Romans didn't describe themselves as white but rather described people from northern Europe this way, noted Draycott. Kenrick said that the Greeks would also not have considered themselves to be white. “Greek should not be equated with white, as the Greeks and Romans certainly didn't consider themselves to be white” Kenrick said.

According to Science: Minoans and Mycenaeans looked alike, both carrying genes for brown hair and brown eyes. Artists in both cultures painted dark-haired, dark-eyed people on frescoes and pottery who resemble each other, although the two cultures spoke and wrote different languages. [Source:Ann Gibbons, Science, August 2, 2017]

How Tall Were Ancient Greeks?

Research by anthropologist J. Lawrence Angel indicates Greco-Roman times men averaged around 5 foot 6 and women averaged around 5 foot 0. People who 5 foot 10 were considered exceptionally tall. In contrast, 30,000 years ago men averaged 5 feet 11 and women averaged 5 foot 6. In 1960, American men averaged 5 foot 9.

Fiona Kotziampasi posted on Quora.com in 2023: Anthropological studies of Greek skeletal remains give mean heights for Classical Greek males of 170.5 centimeters or 5' feet 7.1 inches,. and for Hellenistic Greek males of 171.9 centimeters or 5 feet 7.7 inches, and these figures have been corroborated by further studies of material from Corinth and the Athenian Kerameikos. The average height for a man in Europe today is 180 centimeters, while the average height for a woman in Europe is 167. The average height for modern Greek men is 179 centimeters and the average height for Greek women is 165 centimeters, based on World Data Info.

Eirini Patrikiou posted on Quora.com in 2023: Ancient Greeks were moderately shorter than modern humans, who have much better nutrition than in destitute ancient times. This has been found by reconstructing the human skeleton by a series of different bones. They didn’t become shorter at all, in fact in Byzantine times they became taller, especially the men, and modern humans, including modern Greeks, would tower over most ancient people.

How Long Did Ancient Greeks Live?

The life expectancy of a newborn Greek baby was 21 years. Half of all children died before the age of 15. If a female lived beyond that age she was expected to live to 38; a male to 41. Excavation of burial sites in southern Italy dating between 580 and 250 B.C. show that ancient Greeks had a high infant mortality rate and almost four out five children likely suffered from life-threatening diseases.

Yannis Gaitanas posted on Quora.com in 2023: Most modern sources will give you pretty low numbers. For example encyclopedia Britannica mentions “In ancient Greece and Rome the average life expectancy was about 28 years”. However the thing is that statistics work in a way that lowers the average a lot. It’s not that in older times people wouldn’t reach old age.

The thing is that in antiquity most infants died. If you take the average life expectancy of a family living in a house where the grandma died at 45 and grandpa at 75, mom died at 70 and dad at 48 due to say war, the two kids lived to both become 60 and 70 but there were also kids that died at 2 and four kids that died as babies, then the average life expectancy of the family would be 33,6. This doesn’t mean that people suprassing that age were too old. As one sees in my example, all adults easily did. Men could have died at war or some cancer but still in this example people reached 70 if they surpassed the infancy stage. In fact men in ancient Greece wouldn’t even normally be trusted an important office or start a family before the age of 30, as I explained before,

DNA Evidence Regarding Early Greeks

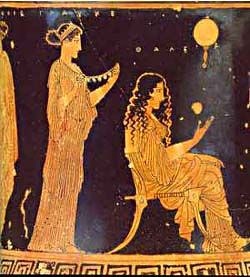

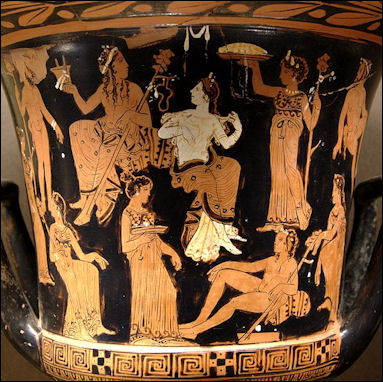

Calyx krater

When scientists compared the ancient DNA of Europe’s earliest farmers to that of modern-day Europeans, they found that the farmer’s DNA was most similar to Mediterranean populations like Cypriots and Greeks. In contrast, the hunter-gatherer DNA most closely resembled northerners like Finns. The simplest explanation for this pattern is that an ancient migration of farmers started in southern Europe and moved northward over many generations, said the researchers, from Uppsala University in Sweden and other institutions in Sweden and Denmark. .”[Source:University of Wisconsin, Madison, February 11, 2013]

Fertile Crescent cultures diverged and took farming east and west based on DNA taken from bone fragment from a 7,000-year-old farmer discovered in a cave in the Zagros region of Iran and the DNA of three other individuals from a second Iranian site. According to Science News: “Sometime after farming was developed, the two cultures began to move apart. Why they spread so differently is still a mystery. More DNA samples from ancient people east of the Fertile Crescent are necessary to confirm that people spread from Iran eastward, says anthropologist Christina Papageorgopoulou of the Democritus University of Thrace in Greece. She coauthored the Anatolian study but was not involved in the new work. [Source: Amy McDermott, sciencenews.org, July 14, 2016 ||-||]

Some think agriculture was carried westward from the Near East suddenly and dramatically in early ships. Remains of boats found in Sardinia and Crete show that men have been crossing seas for more than 10,000 years. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science in June 2016 that supports the idea that at least some migrants came by sea and challenges the notion that farming simply spread from one population to another through cultural diffusion.

See Separate Article: SPREAD OF AGRICULTURE TO EUROPE BY MIGRANTS FROM ANATOLIA (TURKEY) europe.factsanddetails.com

DNA Evidence Connects Modern Greeks with Mycenaeans and Minoans

A 2017 study, based on DNA evidence, suggests that living Greeks are the descendants of Mycenaeans, with only a small proportion of DNA coming from later migrations to Greece. And the Mycenaeans themselves were closely related to the earlier Minoans. Mycenaeans created a famous civilization that dominated mainland Greece and the Aegean Sea from about 1600 to 1200 B.C. Minoans flourished on the island of Crete from 2600 to 1400 B.C.[Source:Ann Gibbons, Science, August 2, 2017]

Ann Gibbons wrote in Science: The ancient DNA comes from the teeth of 19 people, including 10 Minoans from Crete dating to 2900 B.C.E. to 1700 BCE, four Mycenaeans from the archaeological site at Mycenae and other cemeteries on the Greek mainland dating from 1700 B.C.E. to 1200 B.C.E., and five people from other early farming or Bronze Age (5400 B.C.E. to 1340 B.C.E.) cultures in Greece and Turkey. By comparing 1.2 million letters of genetic code across these genomes to those of 334 other ancient people from around the world and 30 modern Greeks, the researchers were able to plot how the individuals were related to each other.

The ancient Mycenaeans and Minoans were most closely related to each other, and they both got three-quarters of their DNA from early farmers who lived in Greece and southwestern Anatolia, which is now part of Turkey, the team reports today in Nature. Both cultures additionally inherited DNA from people from the eastern Caucasus, near modern-day Iran, suggesting an early migration of people from the east after the early farmers settled there but before Mycenaeans split from Minoans.

The Mycenaeans did have an important difference: They had some DNA—4 percent to 16 percent—from northern ancestors who came from Eastern Europe or Siberia. This suggests that a second wave of people from the Eurasian steppe came to mainland Greece by way of Eastern Europe or Armenia, but didn't reach Crete, says Iosif Lazaridis, a population geneticist at Harvard University who co-led the study.

When the researchers compared the DNA of modern Greeks to that of ancient Mycenaeans, they found a lot of genetic overlap. Modern Greeks share similar proportions of DNA from the same ancestral sources as Mycenaeans, although they have inherited a little less DNA from ancient Anatolian farmers and a bit more DNA from later migrations to Greece. The continuity between the Mycenaeans and living people is "particularly striking given that the Aegean has been a crossroads of civilizations for thousands of years," says co-author George Stamatoyannopoulos of the University of Washington in Seattle.

This suggests that the major components of the Greeks' ancestry were already in place in the Bronze Age, after the migration of the earliest farmers from Anatolia set the template for the genetic makeup of Greeks and, in fact, most Europeans. "The spread of farming populations was the decisive moment when the major elements of the Greek population were already provided," says archaeologist Colin Renfrew of the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, who was not involved in the work.

Cousin Marriages Surprisingly Common in Ancient Greece

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: An international team, led by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, produced a scientific study of the genetics of people from a number of Greek islands. The team analyzed more than a hundred samples of genomes from inhabitants from the Neolithic and Middle Bronze age Aegean (17-12th centuries B.C.) and noticed an interesting result: more than half the people who lived on these islands married their cousins. The results were published open access in January 2023 in the prestigious journal Nature Ecology & Evolution. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 22, 2023]

Professor Philipp Stockhammer, a lead author on the study and archeologist at the Max Planck Institute, told CNN that the study was significant for what it revealed about social structures of the communities who lived on the Island. “We managed to construct the first family pedigree for the Mediterranean. We can see who lived together in this house from looking at who was buried outside in the courtyard. We could see, for example, that the three sons lived as adults in this house. One of the marriage partners brought her sister and a child. It’s a very complex group of people living together.”

According to the article the high rates of “consanguineous endogamy” (cross-cousin unions) are “unprecedented in the global ancient DNA record.” Stockhammer explained, “People have studied thousands of ancestral genomes and there’s hardly any evidence for societies in the past of cousin-cousin marriage. From a historical perspective this

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK MARRIAGE: CONTRACTS, COUSINS AND DIVORCE europe.factsanddetails.com

Birth Control and Contraceptives in Ancient Greece

silphion According to historians, demographic studies suggest the ancients attempted to limit family size. Greek historians wrote that urban families in the first and second centuries B.C. tried to have only one or two children. Between A.D. 1 and 500, it was estimated the population within the bounds of the Roman Empire declined from 32.8 million to 27.5 million (but there can be all sorts of reason for this excluding birth control).

Birth control methods in ancient Greece included avoiding deep penetration when menstruation was "ending and abating" (the time Greeks thought a woman was most fertile); sneezing and drinking something cold after having sex; and wiping the cervix with a lock of fine wool or smearing it with salves and oils made from aged olive oil, honey, cedar resin, white lead and balsam tree oil. Before intercourse women tried applying a perceived spermicidal oil made from juniper trees or blocking their cervix with a block of wood. Women also ate dates and pomegranates to avoid pregnancy (modern studies have shown that the fertility of rats decreases when they ingest these foods).

Women in Greece and the Mediterranean were told that scooped out pomegranates halves could be used as cervical caps and sea sponges rinsed in acidic lemon juice could serve as contraceptives. The Greek physician Soranus wrote in the 2nd century A.D. : "the woman ought, in the moment during coitus when the man ejaculates his sperm, to hold her breath, draw her body back a little so the semen cannot penetrate into the uteri, then immediately get up and sit down with bent knees, and this position provoke sneezes."

The ancient Greeks inserted olive oil into thercervix . The Talmud mentions the use of a sponge soaked in vinegar. Intrauterine devices were also used. Books attributed to Hippocrates, the great Greek physician, mention their existence in ancient Greece.

Valuable Ancient Greek Contraceptive Plant

In the seventh century B.C., Greek colonists in Libya discovered a plant called “ silphion” , a member of the fennel family which also includes “ asafoetida” , one of the important flavorings in Worcester sauce. The pungent sap from silphion, the ancient Greeks found, helped relieve coughs and tasted good on food, but more importantly it proved to be an effective after-intercourse contraceptive. A substance from a similar plant called “ ferujol” has been shown in modern clinical studies to be 100 percent successful in preventing pregnancy in female rats up to three days after coitus. [Source: John Riddle, J. Worth Estes and Josiah Russell, Archaeology magazine, March/April 1994]

Known to the Greeks as silphion and to the Romans as silphium, the plant brought prosperity to the Greek city-state of Cyrene. Worth more than is weight on silver, it was described by Hippocrates, Diosorides and a play by Aristophanes.

Sixth century B.C. coins depicted women touching the silphion plant with one hand and pointing at their genitals with the other. The plant was so much in demand in ancient Greece it eventually became scarce, and attempts to grow it outside of the 125-mile-long mountainous region it grew in Libya failed. By the 5th century B.C., Aristophanes wrote in his play “ The Knights” , "Do you remember when a stalk of silphion sold so cheap?" By the third or forth century A.D., the contraceptive plant was extinct.

Abortions in Ancient Greece

silphion symbol Abortions were performed in ancient times, says North Carolina State history professor John Riddle, and discussions about featured many of the same arguments we hear today. The Greeks and Romans made a distinction between a fetus with features and one without features. The latter could be aborted without having to worry about legal or religious reprisals. Plato advocated population control in the ideal city state and Aristotle suggested that "if conception occurs in excess...have abortion induced before sense and life have begun in the embryo.”

The Stoics believed the human soul appeared when first exposed to cool air, and the potential for a soul existed at conception. Hippocrates warned physicians in his oath not to use one kind of abortive suppository, but the statement was misinterpreted as a blanket condemnation of all of abortion. John Chrystom, the Byzantine bishop of Constantinople compared abortion to murder in A.D. 390, but a few years earlier Bishop Gregory of Nyssa said the unformed embryo could not be considered a human being. [Riddle has written a book called “ Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance” ].

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024