Home | Category: Religion and Gods

ANCIENT ROMAN GRAVES AND PLACES OF BURIALS

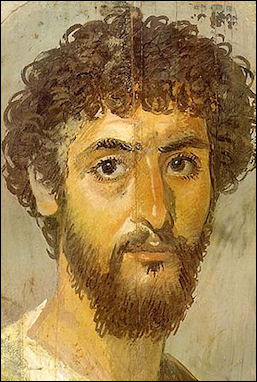

Fayum Egypt Roman-era mummy portrait Graves for people who were buried were dug by professional grave diggers. The poor were often unceremoniously thrown into shallow trench graves or common graves without coffins. Sometimes a half amphora was placed over the grave so that libations could be poured in it. Wealthy Christians were buried in elaborate sarcophagi that were placed in catacombs. If the right arm of the deceased was folded across his chest it may have meant the deceased was a Christian. Sometimes the dead were buried with leaves. A pig was often sacrificed as required by Roman law to make the grave official.

The Twelve Tables forbade the burial or even the burning of the dead within the walls of the city. For the very poor, places of burial were provided in localities outside the walls, corresponding in some degree to the potter’s field of modern cities. The well-to-do made their burial places as conspicuous as their means would permit, with the hope that the inscriptions upon the monuments would keep alive the names and virtues of the dead, and with the idea, perhaps, that the dead still had some part in the busy life around them.To this end they lined the great roads on either side for miles out of the cities with rows of tombs of the most elaborate and costly architecture. In the vicinity of Rome the Appian Way, as the oldest road, showed the monuments of the noblest and most ancient families, but none of the roads lacked such memorials. Many of these tombs were standing in the sixteenth century; few still remain. The custom was followed in the smaller towns, and an idea of the importance of the monuments may be had from the so-called “Street of Tombs” outside of Pompeii. There were other burial places near the cities, of course, less conspicuous and less expensive, and on the farms and country estates like provision was made for persons of humbler station.” [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“During the Republic the Esquiline Hill, or at least the eastern part of it, was the place to which was carted all the refuse of the city that the sewers would not carry away. Here, too, were the grave-pits (puticuli) for the pauper class. They were merely holes in the ground, about twelve feet square, without lining of any kind. Into them were thrown the bodies of the friendless poor, and along with them and over them the carcasses of dead animals and the filth and scrapings of the streets. The pits were kept open, uncovered apparently even when filled, and the stench and the disease-breeding pollution made the hill absolutely uninhabitable. Under Augustus the danger to the health of the whole city became so great that the dumping grounds were moved to a greater distance, and the Esquiline, covered over, pits and all, with pure soil to the depth of twenty-five feet, was made a park, known as the Horti Maecenatis.

“It is not to be understood, however, that the bodies of Roman citizens were ordinarily disposed of in this revolting way. Faithful freedmen were cared for by their patrons, the industrious poor made provision for themselves in cooperative societies, mentioned elsewhere, and the proletariat class was in general saved from such a fate by clansmen, by patrons, or by the benevolence of individuals. Only in times of plague and pestilence, it is safe to say, were the bodies of known citizens cast into these pits, as under like circumstances bodies have been burned in heaps in modern cities. The uncounted thousands that peopled the potter’s field of Rome were the riffraff from foreign lands, abandoned slaves, the victims that perished in the arena, outcasts of the criminal class, and the “unidentified” that are buried nowadays at public expense. Criminals put to death by authority were not buried at all; their carcasses were left to birds and beasts of prey at the place of execution near the Esquiline Gate.” |+|

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Roman Death: The Dying and the Dead in Ancient Rome” by Valerie M. Hope (2009) Amazon.com;

“Death in Ancient Rome” by Catharine Edwards (2015) Amazon.com;

“Death and Burial in the Roman World” by J. M. C. Toynbee (1996) Amazon.com;

“Of Noble Roman Funerals” by Michael Boyajian (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Roman Afterlife: Di Manes, Belief, and the Cult of the Dead” by Charles W. King (2020) Amazon.com;

“After Life in Roman Paganism: The Funeral Rites, Gods and Afterlife of Ancient Rome”

by Franz Valery Marie Cumont (1922) Amazon.com;

“Death as a Process: The Archaeology of the Roman Funeral” by John Pearce and Jake Weekes (2017) Amazon.com;

“Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome” by Donald G. Kyle (2012) Amazon.com;

“Death, Burial and Rebirth in the Religions of Antiquity” by Jon Davies (1999) Amazon.com;

“Roman Tombs and the Art of Commemoration: Contextual Approaches to Funerary Customs in the Second Century CE” by Barbara E. Borg (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Phantom Image: Seeing the Dead in Ancient Rome” by Patrick R. Crowley (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Catacombs: The History and Legacy of Ancient Rome’s Most Famous Burial Grounds” by Charles River Editors (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Catacombs” by Rev. James Spencer Northcote (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Art of the Roman Catacombs: Themes of Deliverance in the Age of Persecution”

by Gregory S Athnos (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Christian Catacombs of Rome: History, Decoration, Inscriptions”

by Vincenzo Fiocchi Nicolai, Fabrizio Bisconti, et al. (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Early Greek Concept of the Soul” by Jan Bremmer (1983); Amazon.com;

Ancient Roman Burial Customs

The Romans burned their dead, with some exceptions. A few of the ancient families, notably the Cornelii, kept to the older fashion of burial, and it was customary even when a body was cremated to take one small portion of bone, called the “os resectum” from the ashes and bury it. The very poor, slaves, and outcasts were buried in graves made to hold a number of bodies, often with little care or respect. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Roman funeral customs, so far as we know them, were very similar to those of Greece. Glass urns were in common use in the western part of the Roman world from the first to the third century A.D. One still contains fragments of bone and ashes.

Under the Empire the custom of burial became frequent among the well-to-do, as is evidenced by the large and costly stone sarcophagi of the period. There is a large Roman sarcophagi from Tarsus. A relief representing the death of Meleager once decorated a sarcophagus. These sculptured scenes are rarely connected with death, but are usually mythical or fanciful.

A grave monument representing a young man and his wife is interesting in that this form of portrait relief within a box-like frame is thought to have been derived from the wax death-masks, “imagines,” enclosed in boxes, which adorned the hall of the Roman noble. A stone cippus or monumen, erected to a mother and her two sons, and decorated with portraits in relief.

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Archaeologists have recently uncovered a large Gallo-Roman necropolis in southwest France. Located just 800 feet from the Roman amphitheater in Saintes, the cemetery may have been the final resting place for many of the arena’s victims. Several hundred graves dating to the first and second centuries A.D. were found, including many double burials, in which two bodies were interred in one trench, lying head to foot. The archaeologists also excavated at least five individuals — four adults and one child — who were still wearing riveted iron shackles around their wrists, necks, or legs. The graves were almost entirely devoid of artifacts, except for that of a young child who was buried with coins on his or her eyes and seven small vases. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2015]

A necropolis in Antequera, Spain, revealed 54 graves and trousseau, belongings collected by a bride for her marriage. The trousseau contained 15 glass ointment vials, two jugs, 25 tokens from the most popular game in ancient Rome and glass beads. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, December 31, 2022]

Roman Burial Societies

aedicula

Early in the Empire, associations were formed for the purpose of meeting the funeral expenses of their members, whether the remains were to be buried or cremated, or for the purpose of building columbaria, or for both. These co-operative associations (collegia funeraticia) started originally among members of the same guild or among persons of the same occupation. They called themselves by many names, cultores of this deity or that, collegia salutaria, collegia iuvenum, etc., but their objects and methods were practically the same. If the members had provided places for the disposal of their bodies after death, they now provided for the necessary funeral expenses by paying into the common fund weekly a small fixed sum, easily within the reach of the poorest of them. When a member died, a stated sum was drawn from the treasury for his funeral, a committee saw that the rites were decently performed, and at the proper seasons the society made corporate offerings to the dead. If the purpose of the society was the building of a columbarium, the cost was first determined and the sum total divided into what we should call shares (sortes viriles), each member taking as many as he could afford and paying their value into the treasury. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Sometimes a benevolent person would contribute toward the expense of the undertaking, and then such a person would be made an honorary member of the society with the title of patronus or patrona. The erection of the building was intrusted to a number of curatores, chosen by ballot, naturally the largest shareholders and most influential men. They let the contracts and superintended the construction, rendering account of all the money expended. The office of the curatores was considered very honorable, especially as their names appeared on the inscription outside the building, and they often showed their appreciation of the honor done them by providing at their own expense for the decoration of the interior, or by furnishing all or a part of the tituli, ollae, etc., or by erecting on the surrounding grounds places of shelter and dining-rooms for the use of the members. |+|

“After the completion of the building the curatores allotted the niches to the individual members. The niches were either numbered consecutively throughout or their position was fixed by the number of the ordo and gradus in which they were situated. Because they were not all equally desirable, as has been explained, the curatores divided them into sections as fairly as possible and then assigned the sections (loci) by lot to the shareholders. If a man held several shares of stock, he received a corresponding number of loci, though they might be in widely different parts of the building. The members were allowed freely to dispose of their holdings by exchange, sale, or gift, and many of the larger stockholders probably engaged in the enterprise for the sake of the profits to be made in this way. After the division was made, the owners had their names cut upon the tituli, and might put up columns to mark the aediculae, set up statues, etc., if they pleased. Some of the tituli give, besides the name of the owner, the number and position of his loci or ollae. Sometimes they record the purchase of ollae, giving the number bought and the name of the previous owner. Sometimes the names on the ollae do not correspond with that over the niche, showing that the owner had sold a part only of his holdings, or that the purchaser had not taken the trouble to replace the titulus. The expenses of maintenance were probably paid from the weekly dues of the members, as were the funeral benefits. |+|

Roman Cemetery in a Provincial Outpost

tombs in Pompeii

At a necropolis just outside the town of Scupi in Macedonia, archaeologists have uncovered more than 5,000 graves dating from the Bronze Age through the Roman period. Matthew Brunwasser wrote in Archaeology magazine: “In the first century A.D. Roman army veterans arrived in what is now northern Macedonia and settled near the small village of Scupi. The veterans had been given the land by the emperor Domitian as a reward for their service, as was customary. They soon began to enlarge the site, and around A.D. 85, the town was granted the status of a Roman colony and named Colonia Flavia Scupinorum. ("Flavia" refers to the Flavian Dynasty of which Domitian was a member.) Over the next several centuries Scupi grew at a rapid pace. In the late third century and well into the fourth, Scupi experienced a period of great prosperity. The colony became the area's principal religious, cultural, economic, and administrative center and one of the locations from which, through military action and settlement, the Romans colonized the region. [Source: Matthew Brunwasser, Archaeology, Volume 65 Number 5, September/October 2012 ~]

“Scupi, which gives its name to Skopje, the nearby capital of the Republic of Macedonia, has been excavated regularly since 1966. Since that time archaeologists have uncovered an impressive amount of evidence, including many of the buildings that characterize a Roman city— a theater, a basilica, public baths, a granary, and a sumptuous urban villa, as well as remains of the city walls and part of the gridded street plan. Recently, however, due to the threat from construction, they have focused their work on one of the city's necropolises, situated on both sides of a 20-foot-wide state-of-the art ancient road. In the Roman world, it was common practice to locate necropolises on a town's perimeter, along its main roads, entrances, and exits. Of Scupi's four necropolises, the southeastern one, which covers about 75 acres and contains at least 5,000 graves spanning more than 1,500 years, is the best researched. The oldest of its burials date from the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age (1200?900 B.C). These earlier graves were almost completely destroyed as Roman burials began to replace them in the first century. According to Lence Jovanova of the City Museum of Skopje, who is in charge of the necropolis excavations, the burials have provided much new information crucial to understanding the lives of ancient Scupi's residents, including the types of household items they used, their life spans, building techniques, and religious beliefs. In just the last two years alone, nearly 4,000 graves have been discovered and about 10,000 artifacts excavated, mostly objects used in daily life such as pots, lamps, and jewelry. ~

“Among the thousands of graves there is a great variety of size, shape, style, and inhumation practice. There are individual graves, family graves, elaborate stone tombs, and simple, unadorned graves. Some burials are organized in regular lines along a grid pattern parallel to the main road, as was common in the Roman world. Other individuals are buried in seemingly random locations within the necropolis area, more like a modern cemetery that has been in use for a long time. The oldest Roman layers, dating to the first through mid-third centuries A.D., contain predominantly cremation burials. The later Roman layers, however, containing graves from the third and fourth centuries A.D., are, with very few exceptions, burials of skeletons. According to Jovanova, this variety in burial practice is normal for this time and reflects a complex, long-term, and regionwide demographic change resulting not only from an increased number of settlers coming from the east, but also from internal economic, social, and religious changes.” ~

Roman Infant Burials

a mosaic on the funeral stele of a young boy

Unlike Christians, Romans did not consider children as beings with a developed soul. As a consequence they often discarded dead infants or buried them in the garden like a dead pet. Laws were passed in the 5th century outlawing the sale of children to families who might give a child a better chance of survival.

An infant graveyard, dated to around A.D. 400, the largest ever discovered, was found near the town of Lugano, 70 miles north of Rome. The bodies of the infants were buried there in earthen jars, with, in some cases, decapitated puppies and raven claws. By this period in history Rome had been Christianized and archaeologists interpret these gruesome pagan offerings as a superstitious act brought on by "extreme stress."

The epitaphs composed for infant tombs also disclose a great deal about the intense grief parents felt towards lost infants. One inscription read that the baby's life consisted of just “nine breaths." In another a father wrote: “My baby Aceva was snatched away to live in Hades before she had her fill of the sweet light of life. She was beautiful and charming, a little darling as if from heaven, her father weeps for her and, because he is her father, asks that the earth may rest lightly on her forever."

Excavations of an ancient sewer under a Roman bathhouse in Ashkleon in present-day Israel revealed the remains of more than 100 infants thought to be unwanted children from the brothel. The infants had been thrown into a gutter along with animal bones, pottery shards and a few coins and are thought to have been unwanted because of the way they were disposed of. DNA tests revealed that 74 percent of the victims were male. Usually unwanted children were girls. Infant mortality may have been the outcome of one third of live births.

Roman Burial Inside a House

In 2010, archaeologist at the University of British Columbia announced that had found a grave inside a room a house at Kaukana, an ancient Roman and Byzantine village on the south coast of Sicily. Normally burials from this period are found in the village cemetery on the outskirts, or else around the village church. Inside the burial were two skeletons – one of a woman aged about 25, and the other of a young child. The discovery was made by a team led by Professor Roger Wilson, Head of Classical, Near Eastern and Religious Studies at UBC. [Source: Loren Plottel, University of British Columbia, April 10, 2010]

cinerary urns

Loren Plottel of the University of British Columbia: “DNA testing in 2009/10 has now confirmed that the woman and child belong to the same family, and the child has been identified, also through her DNA, as a little girl, about four years old: they were clearly mother and daughter. From the way in which her bones were arranged, it is clear the child was placed in the tomb sometime after the mother had been buried. But the discoveries have now got even more interesting. The mother is now known to have been approximately 30 weeks pregnant (some bones of her foetus survived), and periodic feasting occurred at her graveside: not only were dining plates, amphorae for wine and oil, and cooking pots found alongside the tomb, but also ovens where the food they ate was cooked.

“Preliminary analysis of carbonized seeds shows that one meal consisted of wheat, barley, millet, peas, eggs and lentils. There was even a bench provided for the diners, and a low table. One of the amphorae had brought wine all the way from Egypt, and a clay lamp of about 550 CE, imported from Tunisia, is thought to show the earliest depiction of a backgammon board ever found. It is known that this game (a descendant of earlier Roman games) was being played by Roman emperors in the fifth century CE. Clearly the woman, whose tomb had a hole in the lid to take libations of wine, was a much-loved person, given the attention paid to her burial and the evidence of ritual feasting in her honour. The team now also knows, from the discovery of an inscription in 2009, that she was definitely a Christian, since a tomb slab was inscribed ‘holy, holy, holy’, an allusion to part of the early Christian liturgy.

“But why was she so honoured, and why here inside a home within the settlement, and not at the cemetery or church? One discovery of 2009 was that she possessed a tiny hole in her skull, a natural defect which she had had from birth, with the result that the lining of the brain, the meninges, would have protruded from it. The condition, known as meningocoele, would have given her constant headaches and a tendency to suffer from periodic seizures. Perhaps her miraculous powers of recovery on such occasions, apparently coming back from the ‘dead’, meant that she was seen by some as a holy woman, possibly one possessing special mystical powers. Perhaps she was rejected by her local church as being too scary, given her disabilities – one revered by some but feared by others. Or did she belong to a different, non-catholic Christian sect? The cause of her death is unknown, but it might have been due to complications which arose during her pregnancy. Even if questions surrounding this discovery abound, one thing is certain. The woman remained as remarkable in death as she was once in life.”

Roman 'Bed Burials'

In February 2024, archaeologists announced that they had unearthed a 2,000-year-old Roman funerary bed along with five oak coffins and skeletons at a construction site in London.Live Science reported: While three previously known coffins made of Roman timber were found elsewhere in London from the Roman Britain period (A.D. 43 to 410), this marks the first time that a complete funerary bed has been discovered in Britain. Crafted from oak, the bed includes carved feet and joints attached with small wooden pegs. [Source Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, February 5, 2024]

Researchers determined the bed had been dismantled before being placed in the grave "but may have been used to carry the individual to the burial and was likely intended as a grave good for use in the afterlife." In addition to the coffins and the five beds at the London site, researchers unearthed human skeletal remains and various personal effects, including beads, a glass vial and a decorative lamp that date to the very early Roman Britain period (A.D. 48 to 80).

In 2022, archaeologists said they found a burial of woman lying on bronze 'mermaid bed' dated to the first century B.C. near the city of Kozani in northern Greece. The bed is plain looking, and has a rectangular bronze headboard on both ends. It has several wooden slats. The legs are made out of several knobbly bits of bronze, but nothing intricate. According to Live Science: Depictions of mermaids decorate the posts of the bed. The bed also displays an image of a bird holding a snake in its mouth, a symbol of the ancient Greek god Apollo. The woman's head was covered with gold laurel leaves that likely were part of a wreath, Areti Chondrogianni-Metoki, director of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Kozani, told Live Science in an email. The wooden portions of the bed have decomposed. The bronze bed burial was found in 2019. In 2021, another bed burial was found in a nearby cemetery that had an elderly man buried on the remains of a bed made of iron and wood. That burial dated to the fourth century B.C. [Source Owen Jarus, Live Science, June 3, 2022]

Roman-Era Graves with Beheaded Skeletons

In 2022, archaeologists announced the discovery of 40 decapitated skeletons, many with their skulls between their legs next to their feet, among 425 bodies in a late Roman cemetery at Fleet Marston, near Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire in southern England. Archeologists said that one interpretation could be that the decapitated skeletons were criminals or outcasts, although decapitation was a "normal, albeit marginal, burial rite" during the late Roman period. [Source: Alia Shoaib, Business Insider, February 7, 2022]

In 2019, archaeologists made a similar discovery at a fourth century Roman cemetery near Bury St. Edmunds in Suffolk. There 52 skeletons were found at a Roman burial ground at the site, with 40 percent of them buried with the skulls between their legs. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The high proportion of decapitated bodies indicates that these were not the victims of execution and that instead ancient Romans had been dismembering the remains post-mortem and moving around the bodies. The remains include women and children who, almost certainly, had lived nearby in a contemporary settlement. The decapitation took place post-mortem though it is (currently) unclear if the body was excarnated (stripped of flesh) before this took place. Archaeologist Andrew Peacher commented that the discovery gave scientists a “fascinating insight” into the quirky burial practices of Roman-era Britons. He added that the “statistical anomaly of having so many decapitations there” suggests that “we are looking at a very specific part of the population that followed a very specific form of burial.” This find is similar to decapitated skeletons found at Eboracum (modern day York) in late 2000s. Some of these had been punctured by animal attacks, and had asymmetrical musculature (the bane of weight lifters and athletes everywhere), which suggests the bodies belonged to gladiators. [Source Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 12, 2019]

Matthew Brunwasser wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The Roman colony of Scupi in northern Macedonia is the most thoroughly excavated ancient site in the country. Thus archaeologists were shocked when, in fall 2011, they uncovered a completely unknown mass grave on the periphery of the settlement's largest necropolis. By the time they had to stop digging in mid-December due to weather, project leader Lence Jovanova and her team had identified at least 180 adult male skeletons that had been tossed into a pit a foot and a half deep. Many had been decapitated and most had their arms bound behind their backs. Some of the bones show the marks of extreme violence such as cutting and breakage. "It was a terrible sight, like a modern massacre," says Jovanova. When archaeologist Phil Freeman of the University of Liverpool, who specializes in Roman battlefield archaeology, saw images of the excavation, he says his jaw dropped. "The only thing I can think of that is comparable to this is the Vilnius, Lithuania, mass grave from 1812," he remarks, referring to the find 10 years ago of 2,000 well-preserved corpses of French soldiers killed during Napoleon's retreat from Russia. [Source: Matthew Brunwasser, Archaeology, Volume 65 Number 5, September/October 2012]

“Why the men were killed remains a mystery. "All we know is that they died violent deaths. Maybe they were executed. It could have been a war or conflict," Jovanova says, adding that she thinks that whatever did happen occurred near the town, explaining why the victims were buried in the main necropolis. Freeman believes that a mass military execution is the likely scenario. With civil executions, the victims' heads were often placed at the corpses' feet, he explains. None of the Scupi skeletons were found this way.

“Freeman further notes that the grave is not likely the result of a battlefield event. The repeated evidence for decapitation suggests the victims were killed after, not during, battle. It is possible that the mass killing could be linked to the conflicts destabilizing the Roman Empire during the late third to early fourth centuries A.D., according to Jovanova. Freeman agrees that the empire's intense political instability, as different armed factions fought to bring their preferred leader to the emperor's throne, could be tied to the grave in some way. "Our natural tendency is to see the archaeology as simply adjunct to the historical sources," Freeman says. "Since something dates to the first century, for example, it has to fit into a known first-century event. That assumption is made time and time again." But he calls it "a dangerous game" to attempt to match such dramatic finds with known military episodes. Although this may come as a surprise to many, Freeman stresses that there is still a great deal of Roman history that is unknown.”

from the rare book Roman Funeral Customs

Tombs in Ancient Rome

Most people were buried without tombs or under simple gravestones or receptacles used for collecting libations. Only the wealthy could afford tombs and these were generally set up on roads leading into the cities. Exedra were niche tombs. They were two to four meters tall and usually had an altar placed above the ashes. There were often inscriptions praising the dead and a bench for people to sit down on. Some people were buried in “cinerary urns” — semi-transparent glass spheres larger than a basketball and filled with a heap of shattered bones.

The tombs, whether intended to receive the bodies or merely the ashes, or both, differed widely in size and construction according to the different purposes for which they were erected. Some were for individuals only, but these in most cases were strictly public memorials as distinguished from actual tombs intended to receive the remains of the dead. The larger number of those that lined the roads were family tombs, ample in size for whole generations of descendants and retainers of the family, including hospites, who had died away from their own homes, and freedmen. Others were erected on a large scale by speculators who sold at low prices space for a few urns to persons not rich enough to erect tombs of their own and without any claim on a family or clan burying place. In imitation of these structures others were erected on the same plan by burial societies formed by persons of the artisan class and others still by benevolent men, as baths and libraries were erected and maintained for the public good. Something will be said of the tombs of all these kinds after the public burying places have been described.” |+|

Catacombs are subterranean rock-cut burial chambers, often with many people buried inside. They were often used in Roman times for the burial of Christians. Many catacombs are on the Via Appia Antica three miles south of Rome. After Christianity was embraced by the Roman Empire some of these catacombs became quite elaborate. Some had long passageways with chambers off of which the tombs were placed. Some had banqueting tables symbolizing the last supper. Some of the earliest known Christian art comes from these.

Etruscan Tombs

Some Etruscan tombs are entirely underground. Some are half above ground and are built up with masonry. Many are covered under conical mounds. Some of these are very complex, with false doors and pseudo-vaulted roofs held up by single pillars. A few have been found cut into cliff faces. The tomb art deals mostly with pleasant scenes: parties, dances, games, hunts.

Some 6,000 Etruscan tombs have been found in the Tarquinia region. Many of them have stairwells covered by tile roof structures. The Etruscan put much care into their tombs which were carved often out of solid stone. The tombs were like the inside of a normal house. About 200 of the tombs that have been excavated contain colorful painted walls and vaults. Mnay of the tombs have been ravaged by looters.

Inside the Etruscan Tomb of the Leopards in Tarquinia

In 2007, a team from the University of Turin began excavating the largest tomb in Tarquinia. Known as the Queen's Tomb, it is 40 meters in diameter and is similar to another monumental tomb, 200 meters away: The King's Tomb. The entrance of the Queen's Tomb faces west-northwest , where according to to Etruscan religion , the gods of the underworld live. The staircase descends about 20 feet into an almost six -square-meter room. Made of large limestone blocks. Some of the wlls were plasters with a special kind of crystal-filled gypsum imported from Cyprus. There are trace sof paint thought to have be from a painting of a duck, which the Etruscans believed guided the dead to the afterlife. One unusual feature of the Queen's tomb is an extra room which is believed to have been used in rituals, sacrifices and making offerings to the dead. In nearby tombs archeologist found some stone beds and broken cups from which wine was consumed.

Cervterie, which embraces hundreds of acres of Banditaccai tombs, is the most impressive Etruscan necropolis discovered so far. At the mains are several circular tombs that a topped by piles of earth. Flanking these are several terraces of flat box-shaped tombs that are covered with bushes and trees. Most of the tombs have entrances.

In the Tomb of the Reliefs a model has been set up that depicts what the home of the a typical Etruscan dead person looks like. Hanging from carved rectangular pillars are axes, urns and knives. Around the burial chambers are carvings of three-headed dogs and hunters.

Types and Designs of Roman Tombs

The utmost diversity prevails in the outward form and construction of the tombs, but those of the classical period seem to have been planned with the thought that the tomb was to be a home for the dead and that they were not altogether cut off from the living. The tomb, therefore, whether built for one person or for many, was ordinarily a building inclosing a room (sepulcrum); this room was the most important part of the tomb. Attention has been called to the fact that even the urns had in ancient times the shape of the house of one room. The floor of the sepulcrum was quite commonly below the level of the sur rounding grounds and was reached by a short flight of steps. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Around the base of the walls ran a slightly elevated platform (podium) on which were placed the coffins of those who were buried, while the urns were placed either on the platform or in the niches in the wall. An altar or shrine is often found, at which offerings were made to the manes of the departed. Lamps are very common and so are other simple articles of furniture, and the walls, floors, and ceilings are decorated in the same style as those of houses. Things that the living had liked to have around them, especially things that they used in their ordinary occupations, were placed in the tomb with the dead at the time of burial, or burned with them on the funeral pyre; an effort was made to give an air of life to the chamber of rest. |+|

Roman graves

“The monument itself was always built upon a plot of ground as spacious as the means of the builders would permit; sometimes it was several acres in extent. In it provision was made for the comfort of surviving members of the family, who were bound to visit the resting place of their dead on certain regularly recurring festivals. If the grounds were small, there would be at least a seat, perhaps a bench. On more extensive grounds there were places of shelter, arbors, or summer houses. Dining-rooms, too, in which were celebrated the anniversary feasts, and private ustrinae (places for the burning of bodies) are frequently mentioned. Often the grounds were laid out as gardens or parks, with trees and flowers, wells, cisterns or fountains, and even a house, and other buildings perhaps, for the accommodation of the slaves or freedmen who were in charge. In the middle of the garden is placed the area, that is, the plot of ground set aside for the tomb, with several buildings upon it, one of which is a storehouse or granary (horreum); around the tomb itself are beds of roses and violets, used in festivals; around them in turn are grapes trained on trellises (vineolae). In front is a terrace (solarium), and in the rear two pools (piscinae) connected with the area by a little canal, while at the back is a thicket of shrubbery (harundinetum). The purpose of the granary is not clear, as no grain seems to have been raised on the lot, but it may have been left where it stood before the ground was consecrated. A tomb surrounded by grounds of some extent was called a cepotaphium.” |+|

There were many forms of Roman tombs. “Monuments shaped like altars and temples are most common, perhaps, but memorial arches and niches are often found. At Pompeii the semicircular bench that was used for conversation out of doors occurs several times, covered and uncovered. Not all the tombs have the sepulchral chamber; the remains were sometimes deposited in the earth beneath the monument. In such cases a tube or pipe of lead ran from the receptacle to the surface, through which offerings of wine and milk could be poured.

“In the northern part of the Campus Martius, Augustus built a mausoleum for himself and family in 28 B.C. This was a great circular structure of concrete with marble or stucco facing. Above was a mound of earth planted with trees and flowers, on the summit of which stood a statue of Augustus. On each side of the entrance were the famous bronze tablets inscribed with the Res Gestae, the record of his work. The ashes of the young Marcellus were the first placed here, in 28 B.C., and those of the Emperor Nerva the last, in 98 A.D. The mausoleum was plundered by Alaric in 419 A.D. In medieval times it became a fortress of the Colonna. About 1550 the Soderini made it into hanging gardens. It has been a bull ring and a circus, and is now a concert hall. The most imposing of all the tombs was the Mausoleum of Hadrian at Rome, now the Castle of St. Angelo. |+|

Columbaria

From the family tombs were developed the immense structures, structures which were intended to receive great numbers of urns. They began to be erected in the time of Augustus, when the high price of land made the purchase of private burial grounds impossible for the poorer classes. An idea of their interior arrangement may be had from the ruins of one erected on the Appian Way and of one at Ostia. From their resemblance to a dovecote or pigeon house they were called columbaria. They are usually partly underground, rectangular in form, with great numbers of the niches (also called columbaria) running in regular rows horizontally (gradus) and vertically (ordines). [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“In the larger columbaria provision was made for as many as a thousand urns. Around the walls at the base was a podium, on which were placed the sarcophagi of those whose remains had not been burned, and sometimes chambers were excavated beneath the floor for the same purpose. In the podium were also niches, that no space might be lost. If the height of the building was great enough to warrant it, wooden galleries ran around the walls. Access to the room was given by a stairway in which were niches, too; light was furnished by small windows near the ceiling, and walls and floors were handsomely finished and decorated. |+|

Columbarium in the Vigna Codini on the Appian Way

“The niches were sometimes rectangular in form, but more commonly half round, as shown in Figures 306 and 310. Some of the columbaria have the lower rows rectangular, those above arched. They contained ordinarily two urns (ollae, ollae ossuariae) each, arranged side by side, that they could be visible from the front. Occasionally the niches were made deep enough for two sets of urns, those behind being elevated a little over those in front. Above or below each niche was fastened to the wall a piece of marble (titulus) on which was cut the name of the owner.

“If a person required for his family a group of four or six niches, it was customary to mark them off from the others by wall decorations to show that they made a unit; a very common way was to erect pillars at the sides so as to give the appearance of the front of a temple. Such groups were called aediculae. The value of the places depended upon their position; those in the higher rows (gradus) were less expensive than those near the floor; those under the stairway were the least desirable of all. The urns themselves were of various materials and were usually cemented to the bottom of the niches. The tops could be removed, but they, too, were sealed after the ashes had been placed in them; small openings were left through which offerings of milk and wine could be poured. On the urns, or their tops, were painted the names of the dead, with sometimes the day and the month of death. The year is rarely found. Over the door of such a columbarium on the outside was cut an inscription giving the names of the owners, the date of erection, and other particulars.” |+|

An inscription at one Columbarium reads: “Lucius Abucius Hermes [has acquired] in this row, running from the lowest tier to the highest, nine niches with eighteen urns for [the ashes of] himself and his descendants. This citizen has been surrendered to death. For those who find it convenient, it is now time to attend the funeral. He is being brought from his house.”

Roman Sarcophagi

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “A sarcophagus (meaning "flesh-eater" in Greek) is a coffin for inhumation burials, widely used throughout the Roman empire starting in the second century A.D. The most luxurious were of marble, but they were also made of other stones, lead, and wood. Prior to the second century, burial in sarcophagi was not a common Roman practice; during the Republican and early Imperial periods, the Romans practiced cremation, and placed remaining bones and ashes in urns or ossuaries. Sarcophagi had been used for centuries by the Etruscans and the Greeks; when the Romans eventually adopted inhumation as their primary funerary practice, both of these cultures had an impact on the development of Roman sarcophagi. The trend spread all over the empire, creating a large demand for sarcophagi during the second and third centuries. Three major regional types dominated the trade: Metropolitan Roman, Attic, and Asiatic. [Source: Heather T. Awan, Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Rome was the primary production center in the western part of the empire, beginning around 110–120 A.D. The most common shape for Roman sarcophagi is a low rectangular box and a flat lid. The kline lid, with full-length sculptural portraits of the deceased reclining as if at a banquet, was inspired by earlier Etruscan funerary monuments. This type of lid gained popularity in the later second century, and was produced in all three production centers for very lavish sarcophagi. The lenos, a tub-shaped sarcophagus resembling a trough for pressing grapes, was another late second-century development, and often features two projecting lion's head spouts on the front. Most western Roman sarcophagi were placed inside mausolea against a wall or in a niche, and were therefore only decorated on the front and two short sides. A large number are carved with garlands of fruit and leaves, evoking the actual garlands frequently used to decorate tombs and altars. Narrative scenes from Greek mythology were also popular, reflecting the upper-class Roman taste for Greek culture and literature. Other common decorative themes include battle and hunting scenes, weddings and other biographical episodes from the life of the deceased, portrait busts, and abstract designs such as strigils. Simpler, less expensive sarcophagi were commissioned by freedmen and other nonelite Romans, and sometimes featured the profession of the deceased. \^/

sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus

“The main production center of Attic sarcophagi was Athens. The nearby quarry on Mount Pentelicus supplied the marble, and the workshops produced sarcophagi mainly for export. Attic sarcophagi are typically rectangular in shape, decorated on all four sides, with elaborate ornamental carving along the base and upper edge. Lids usually have the form of a steeply pitched gabled roof. Mythological subjects were the most popular form of decoration, especially the Trojan War, Achilles, and Amazon battles, and reflect the style and compositions of Classical Greek art. \^/

“In Asia Minor, the use of sarcophagi has a long history in certain regions. During the Roman Imperial period, the major production center of Asiatic sarcophagi was Dokimeion in Phrygia. The Dokimeion workshop specialized in large-scale sarcophagi with an architectural form. Colonnades extend around all four sides, with male and female figures in the intercolumniations, and a doorway motif on one side. The lids are mostly the gabled-roof type with ornamental akroteria. The architectural style may have been inspired by earlier royal funerary monuments such as the fourth-century B.C. Mausoleum of Halicarnassos. Some scholars see this style of sarcophagus as a "house" for the deceased, while others consider it a "temple" to a heroized deceased. Other cities in Asia Minor also produced large quantities of sarcophagi, some following the architectural format, and others decorated with leafy garlands supported by Nikai and Erotes, inscribed tabulae, and Gorgon faces. They were decorated on either three or four sides, and were displayed in a wide variety of ways. Many were viewed in the round in open-air settings, either elevated on pedestals or placed on the roofs of built tombs, but some were also placed inside tombs against walls. \^/

“Some quarries, for example Prokonessos in Asia Minor, produced and exported half-finished sarcophagi. These had the main decorative elements roughly blocked out, to be more fully developed at their destination according to a client's taste. Sometimes the sarcophagi were used with some elements unfinished, perhaps due to constraints on time or finances, but possibly due to a client's preference. In Roman Egypt, a special form of coffin developed, which combined traditional Egyptian mummy cases with painted portraits on wood panels, rendered in the Roman style. \^/

“Mythological iconography on sarcophagi has been a subject of considerable interest; the myths shown on sarcophagi are often the same as those chosen to decorate homes and public spaces, but they can acquire different meanings when viewed in a funerary context. Some scholars think the images are highly symbolic of Roman religious beliefs and conceptions about death and the afterlife, while others argue that the images reflect a love of classical culture and served to elevate the status of the deceased, or that they were simply conventional motifs without deeper significance. For instance, the myths of Endymion and Eros and Psyche are tales of mortals who are loved by divinities and granted immortality; in funerary art, these scenes are thought to express the hope for a happy afterlife in the heavens. Scenes featuring heroes such as Meleager or Achilles can be expressions of the bravery and virtue of the deceased. Dionysiac scenes evoke feelings of celebration, and release from the cares of this world; the cult of Dionysos also seemed to offer hope for a pleasureable afterlife. Gorgon faces are apotropaic images for protection against evil forces. The Seasons can represent nature's cycles of death and rebirth, or the successive stages of human life. Nikai, personifications of Victory, are often said to represent victory over death, but they could also represent the success of the deceased during his or her life. It is likely that these images had multiple levels of interpretive possibilities, which varied among individual viewers. The use of sarcophagi continued into the Christian period, when they became an important medium for the development of early Christian iconography.”

Romanized Mummies and Ancient Roman Mummy Paintings

Egyptians continued to be embalmed, mummified and laid to rest in Egyptian-style tombs during the periods when Ptolemic Greeks and Romans occupied Egypt. The mummies and their tombs showed Egyptian, Greek and Roman influences. The practice of mummification began to disappear around the A.D. 4th century when Christianity began to flourish.

Romanized Egyptians often put more work into the exterior decorations of the mummy coverings than on the mummification process. The dead were embalmed and wrapped as mummies. Painted portraits of the deceased were made on shrouds wrapped around the mummy wrappings. The portraits were sometimes quite beautiful and realistic. They were painted on linen and plaster. Sometimes they were covered with gold.

Arguably, some of the greatest Roman paintings were produced by Romanized Egyptians, who embalmed their dead, wrapped them as mummies, and painted portraits of the deceased on small wooden panels attached at the head of the shroud wrapped around the mummy wrappings. Sometimes these mummies were put on display before they were buried.

Mummy paintings were rendered from life using colored beeswax on wood panels bounded by linen strips on the outside of the mummy. Pigments mixed with hot wax were used by the Greeks to paint their warships. The Romans used this technique to make portraits on mummy cases in the Fayum region. It is nor clear whether it is the Egyptian influence or the Roman influence that makes the works so exquisite.

See Separate Articles: ROMAN-ERA MUMMIES: RITUALS, GOLD AND PORTRAITS OF THE DEAD europe.factsanddetails.com ; STUNNING, ROMAN-ERA, FAIYUM MUMMY PORTRAITS europe.factsanddetails.com

Stunning Tomb with Ichthyocentaurs and Cerberus

In October 2023, archaeologist announced that they had unearthed a 2,200-year-old tomb painted with two uncommon mythical creatures — a pair of ichthyocentaurs, or sea-centaurs, which have the head and torso of a man, the lower body of a horse and the tail of a fish — during an excavation near Naples. The tomb’s hypogeum — a large tomb with chambers or niches for burying several people — was perfect condition, its entrance still covered with tiles. [Source: Kristina Killgrove, Live Science, October 14, 2023]

The tomb is now known as the Tomb of Cerberus. Kristina Killgrove wrote in Live Science: Inside the tomb, numerous frescoes adorn the walls. The two ichthyocentaurs may be depictions of Aphros and Bythos, a pair of mythological sea gods who are the personification of sea foam and the ocean abyss. The sea gods are often shown wearing lobster-claw crowns, but on the wall of this tomb, they are reaching toward each other to hold a large shield known as a clipeus. Two winged, Cupid-like babies complete the scene.The tomb is also covered in painted garlands and features a stunning painting of Cerberus, the mythical three-headed dog who guarded the Roman underworld, who is being captured by the demigod Hercules in the last of his 12 labors. The god Mercury, identifiable by his winged hat, stands nearby.Also included in the tomb are an altar on which family members could leave gifts for the dead, as well as the funeral beds themselves, on which the deceased still rest.

The undisturbed tomb dates to between 194 B.C. and A.D. 27. The discovery was made in the Giugliano region, today a suburb about 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) northwest of Naples. Giugliano was one of the smaller inhabited parts of Campania, a fertile region that in ancient times included cities from Capua to Salerno. On what was found in the tomb, Archaeology magazine reported:. Having captured or killed other monstrous beasts, Hercules, with the god Mercury as one of his guides, descended to the underworld to steal Cerberus, the three-headed guard dog, and bring the creature to the surface. Inside the tomb, Simona Formola, head archaeologist of the Archaeological Superintendency for the Metropolitan Area of Naples, found three painted couches, an altar with libation vessels, and the deceased’s remains. “No similar discovery has previously been made in this area, and usually all that is found are modest burials in earthen pits, almost all of which have already been disturbed,” she says. “This discovery is exceptional due to the monumentality of the tomb and its intact state.” [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, March/April 2024]

According to Live Science later excavations revealed the skeleton of an individual who was covered in a shroud and surrounded by various grave goods, including jars of ointment and a strigil, a Roman personal hygiene tool used to scrape off dirt, perspiration and oil before a person bathed. The deceased, who was in an "excellent state of preservation," according to the Italian Ministry of Culture, had been buried on their back. It appears that the "particular climatic conditions of the funerary chamber" had mineralized the shroud, according to the statement. Ancient pollen samples from the tomb suggest the deceased was treated with creams containing absinthe, as well as Chenopodium, a genus of herbaceous, flowering plants also called goosefoot, according to the statement.[Source Laura Geggel, Live Science, July 30, 2024]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and "The Private Life of the Romans”

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024