Home | Category: Christianized Roman Empire / Christianity and Judaism in the Roman Empire / Early History of Christianity

CHRISTIANITY IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE

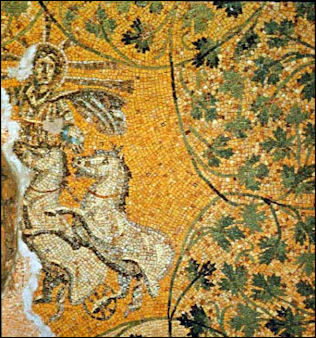

Christ as the sun in

a Roman Christian catacomb Christianity emerged in the Roman Empire during a period of cultural conflict, economic dislocation, political change and migration from the countryside to the cities. Farming villages were being consolidated into large plantations causing a great deal of social dislocation as previously independent farmers were transformed into serflike tenant farmers.

While Roman authorities were promoting universal allegiance to an imperial power, early Christian missionaries provided al alternative of self-supporting communities whose aim was to create a kingdom of God.The ease of travel and the tolerance of new religions in the Roman Empire helped Christianity spread throughout the Middle East, Europe and northern Africa. Christianity end up preserving the legacy of Rome through its language, literature, scientific beliefs, architecture and laws.

Roman authorities for a time tolerated Christian sects and even protected St. Paul on one occasion when his life was in danger. Christians started to be persecuted when they refused to attend games (because they were held on the Sabbath), serve in the army and worship Roman gods. Subjects from all religions were expected to make sacrifices to the Roman gods and worship the Roman emperor as a god.

According to the BBC: “Paul established Christian churches throughout the Roman Empire, including Europe, and beyond - even into Africa. However, in all cases, the church remained small and was persecuted, particularly under tyrannical Roman emperors like Nero (54-68), Domitian (81-96), under whom being a Christian was an illegal act, and Diocletian (284-305). Many Christian believers died for their faith and became martyrs for the church (Bishop Polycarp and St Alban amongst others). “When a Roman soldier, Constantine, won victory over his rival in battle to become the Roman emperor, he attributed his success to the Christian God and immediately proclaimed his conversion to Christianity. Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire. Constantine then needed to establish exactly what the Christian faith was and called the First Council of Nicea in 325 AD which formulated and codified the faith. |[Source: BBC, June 8, 2009 ]

Websites and Resources: Early Christianity: PBS Frontline, From Jesus to Christ, The First Christians pbs.org ; Elaine Pagels website elaine-pagels.com ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Gnostic Society Library gnosis.org ; Guide to Early Church Documents iclnet.org; Early Christian Writing earlychristianwritings.com ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org; Saints and Their Lives Today's Saints on the Calendar catholicsaints.info ; Saints' Books Library saintsbooks.net ; Saints and Their Legends: A Selection of Saints libmma.contentdm ; Saints engravings. Old Masters from the De Verda collection colecciondeverda.blogspot.com ; Lives of the Saints - Orthodox Church in America oca.org/saints/lives ; Lives of the Saints: Catholic.org catholicism.org

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Patient Ferment of the Early Church: The Improbable Rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire” by Alan Kreider Amazon.com ;

“The Church and the Roman Empire (301–490): Constantine, Councils, and the Fall of Rome” by Mike Aquilina Amazon.com ;

“Pagans and Christians” by Robin Lane Fox (1986) Amazon.com

“Foxe's Book of Martyrs: Pure Gold Classics” by John Foxe, Tim Côté, et al Amazon.com ;

“The New Encyclopedia of Christian Martyrs” by Mark Water Amazon.com ;

“Myth of Persecution” by Candida Moss Amazon.com ;

“Constantine the Great” by Michael Grant Amazon.com ;

“Constantine the Great: And the Christian Revolution” by G. P. Baker Amazon.com ;

“The Seven Ecumenical Councils” by Henry R Percival, Philip Schaff, et al Amazon.com ;

“The General Councils: A History of the Twenty-One Church Councils from Nicaea to Vatican II by Christopher M. Bellitto Amazon.com ;

“The New Testament in Its World: An Introduction to the History, Literature, and Theology of the First Christians” by N. T. Wright and Michael F. Bird Amazon.com ;

“When the Church Was Young: Voices of the Early Fathers” by Marcellino D'Ambrosio Amazon.com ;

“When Christians Were Jews: The First Generation” by Paula Fredriksen, Matthew Lloyd Davies, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Early Christian Writings: The Apostolic Fathers” by Andrew Louth and Maxwell Staniforth Amazon.com ;

“Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years” by Diarmaid MacCulloch, Walter Dixon, et al. Amazon.com ;

“A History of Christianity” by Paul Johnson, Wanda McCaddon, et al. Amazon.com

Christians in Rome and the the Roman Empire

After the time of Julius Caesar there was sizable Jewish community in the city of Rome. It was through this Jewish group, its is presumed, that the first Christians coming from Jerusalem penetrated into Rome. Although the famous Roman writers Martial and Juvenal lived at the time same time as early Christian communities and though Pliny the Younger presumably came face to face with Christians in Bithynia but all of them had little or nothing to say about Christians. Tacitus and Suetonius speak of them only from hearsay, with Tacitus using abusive language to describe them. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” By Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: The first evidence we have that the Roman state took notice of Christianity is an ambiguous reference in Suetonius' Life of the emperor Claudius, which reports rioting in the Jewish community in Rome, the cause of which was "Chrestos." But by the reign of Nero, Christians were clearly recognized as a sect separate from mainline Judaism, and after the Great Fire in Rome, Nero sought to deflect blame from himself by persecuting them. Some Romans suspected the Christians of setting the fire, and possibly some Christian millenarians were impolitic enough to rejoice at seeing Rome burn, thinking this was a sign of the Second Coming. The emperor Domitian executed a cousin, Flavius Clemens, for "atheism, for which offense a number of other also, who had been carried away into Jewish customs, were condemned …." (Cassius Dio, 67.14), and historians have suspected that Clemens may have been a Christian. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

However, it was not until the reign of Trajan that Rome's official position was spelled out. Pliny the younger addressed a letter (Epist. 10.96) to Trajan from Bithynia in A.D. 110 to report that he had found a cell of Christians in his province and asked what the proper legal procedure was. Specifically, he wanted to know if Christianity was a crime per se, or was it necessary to prove crimes attached to Christianity, for there were rumors of immoral rites practiced by Christian sects, but the worship Pliny unearthed was innocuous. Yet Trajan ruled that Christianity was a crime per se. But he would not sanction anonymous denunciations or witch-hunts.

See Letters Between Trajan and Pliny the Younger on Christians in Asia Minor Under TRAJAN (RULED A.D. 98-117): HIS CONQUESTS, RULE, LETTERS AND THE PROVINCES europe.factsanddetails.com

Jesus and the Romans

arrest of Jesus

At the time of Christ, Palestine (present-day Israel) was a poorly-run, repressive Greek- and Aramic-speaking Roman colony that had been conquered by Pompey in 63 B.C. After the conquest Palestine was run by a Roman-Jewish government under Herod the Great (37-4 B.C.) who enjoyed considerable autonomy and ruled in such a way that both the Romans and local population were reasonably happy despite his sometimes despotic ways.

Herod the Great was a Jewish leader installed by the Romans. Regarded as puppet king of the Roman Senate, he took power in 37 B.C. and ruled until around 4 B.C. and served under Julius Caesar, Mark Antony and the Emperor Augustus. The rulers after Herod — namely Archelaus, who inherited a third of Herod’s land, including Judea and Jerusalem — were not so good. After 10 years Roman prefects took over Archelaus’s territory. The other portions of Herod’s former lands, including Jesus’s state of Galilee remained under Jewish rule. This arrangement remained until the Roman crackdown after the Jewish revolt and the destruction of the Second Temple in A.D. 70.

Jesus was arrested by Roman police who burst in on Jesus and his disciples as they were praying in the Garden of Gethsemane after the Last Supper. The police were led to the garden by Judas, A violent struggle ensued in which Peter drew his sword and sliced off the ear of one policeman. When Jesus was grabbed, the fighting stopped and the disciples ran away. When the Romans asked Peter if he knew Jesus, Peter denied he did (three times) just as Jesus predicted. Peter “went outside and wept bitterly.” He later repented his denial.

Jesus was brought to trial in Jerusalem in April in A.D. 30 or A.D. 33. He was tried twice in two separate trials. The first one was at a Jewish high court for Sanhedrin (the Jewish tribunal and ruling body). The second trial was before a Roman secular court presided over by a minor prosecutor named Pontius Pilate, who asked Jesus a few cursory questions and ordered his crucifixion. After the sentencing Pilate famously washed his hands to show the fate of Jesus was no longer a matter of which he had any control over. Jesus was then mocked, spat upon and slapped around. He was taken away by Roman guards who harassed and tortured him the night before his execution.

The Romans found Jesus guilty of sedition not blasphemy — a civil crime not a religious one. The men that were crucified with him were identified in some translations as “thieves.” The word can also mean “insurgents.” Jesus' condemnation by Pontius Pilate is described Matthew 27:11-24; Mark 15:1-15; Luke 23:1-25; and John 18:28-19:16.

RELATED ARTICLES:

LAST SUPPER, ARREST OF JESUS AND EVENTS BEFOREHAND

TRIALS OF JESUS africame.factsanddetails.com

TRIALS OF JESUS factsanddetails.com

PASSION OF CHRIST AND THE WAY OF SORROW factsanddetails.com

CRUCIFIXION OF JESUS, EVENTS AND THE STATIONS OF THE CROSS africame.factsanddetails.com

CRUCIFIXION: HISTORY, EVIDENCE OF IT AND HOW IT WAS DONE europe.factsanddetails.com

Christianity Takes Shape Under the Romans

Christain catacomb painting of the Virgin and Child

Professor Shaye I.D. Cohen told PBS: “The triumph of Christianity is actually a very remarkable historical phenomenon. ... We begin with a small group from the backwaters of the Roman Empire and after two, three centuries go by, lo and behold that same group and its descendants have somehow taken over the Roman Empire and have become the official religion, in fact the only tolerated religion, of the Roman Empire by the end of the 4th century. That is a truly remarkable development, and a monumental historical problem, trying to understand how this happened. Of course, pious Christians have no doubt about how or why it happened: "This is the hand of God working in history." And the Christians of antiquity already made this very point; the fact that Christianity triumphed is proof of its truth.

“The second century of our era was the age of definition before Christianity. Now that it realized it no longer was Judaism, or no longer was a form of Judaism, it had to figure out, well then, what is it exactly? What is Christianity? What makes it not Judaism, what makes it not Jewish? How is it able to somehow at one and the same time hold on to the Jewish Scriptures, what we call the Old Testament, and still not be Judaism, and still not be Jewish? This was one of the major questions confronting Christian thinkers, writers, church leaders in the second century. This was the great age of Christian diversity, sects, schools, heresies of all kinds, confronting Christian thinkers, and it was only in the second century that we begin to see the emergence of what we might call an orthodoxy, or something that might simply be called "Christianity" in a kind of uniform body of doctrines and text, that is to say, the New Testament. The New Testament as a collection of texts is a product of the second century, as the church figured out which books are sacred, which books are authoritative and which ones are not. ...

“By the third century of our era, we have something called Christianity with its own sacred books, its own rituals, its own ideas, but this is the great age of confrontation with the Roman Empire. The third century, of course, the great age of persecutions, where the Roman Empire now wakes up and realizes that there is something new, and from their perspective, sinister, afoot in new groups that are threatening the social order and ultimately the political order of the Empire. And the Roman Empire was correct. The Romans correctly intuited that the victory of Christianity would mean the end of the Roman Empire, the end of the classical world. ... We often think of persecution, of course, in a Christian perspective. We see it as heroic martyrs confronting the might of Rome, which is true. And the martyrs are indeed a wonderful spectacle and do present a wonderful demonstration of Christian faith. That is certainly true. By the same token, we must realize that the Roman Empire was doing what all bureaucracies do. It was trying to protect itself, trying to perpetuate itself....

“The Romans tried to beat down Christianity but failed. By the fourth century Christianity becomes the state religion and by the end of the fourth century it is illegal to do any form of public worship other than Christianity in the entire Roman Empire. There is a great mystery in how this happened — how such an extraordinary reversal, that begins with Jesus who is executed by the Romans as a public criminal, as a threat to the social order, and somehow we wind up three centuries later with Jesus being hailed as a God, as part of the one, true God who is the God of the new Christian Roman Empire. There is a remarkable progress, a remarkable development in the course of three centuries. ... It's hard to understand exactly how it happened or why it happened, but it is important to realize that we have a progression and a set of developments, and that Christianity by the fourth century is not the same as the Christianity that we see in the first or even the second.

Christianity Takes Hold in Rome

Worship in the Catacombs of Saint Calixtus Despite the persecutions, Christianity managed to grow. Because Christianity was more open to people from all walks of life, it won more converts than Judaism. It also capitalized on discontent in the Roman Empire. Public distaste of emperor worship led to a deep interest across the Roman Empire in Christianity as well mystical cults from Greece and the Middle East.

Persecution helped strengthen Christianity by encouraging communication between churches to warn them of a common danger, by inspiring members to emulate the courage of the martyrs, and by fostering a bonding within and among Christian communities.

As time went on Rome became the center of the Catholic-Christian church. It was more centrally located and stable than Jerusalem. Christmas was invented in Rome, where celebrations — that grew out feasts for the Persian sun-god Mithras — honoring Christ's birthday date back to the forth century.

By the beginning of the A.D. 3rd century, there were about 220,000 Christians in the Roman Empire. At the beginning of the 4th century it had an estimated 6 million followers. After Diocletian abdicated in A.D. 305, Galerius became the leader in the East. In A.D. 311, he issued an edict permitting Christians to worship as they pleased.

Roman Leadership During the Early Christian Period (A.D. 49 - 305)

About A.D. 49 Claudius expelled Jews from Rome because of a disturbance. Persecution under Nero after the Great Fire in Rome seems to be less than what was long reported. The only martyrs of whom there is some plausibility are Peter and Paul. The persecution was a local police action limited to the city of Rome. It was probably not associated with a fire. Even so Nero's name has ever since been associated with a policy of persecution. The real major empire-wide persecution began around 200 years after Nero’s death under the Roman Emperor Decius, who rule from A.D. 249 to 251. [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu /~]

The philosopher emporer Marcus Aurelius persecuted Christians

“Flavians (69-79); At peace under Vespasian. No traces of martyrs. Titus was likewise tolerant, tho these two together destroyed Jerusalem. Domitian alleged to have persecuted (I Cl) Some died, but may have been involved in a plot against Domitian. First explicit reference to a persecution comes 125 years later (Dio Cassius). Traditionally John was exiled to Patmos and Revelation written. Eusebius says "many suffered martyrdom under Domitian," but evidence is scanty. Story of the descendants of Jude. Revelation indicates Christians were certainly being harassed in Asia Minor. /~\

“Antonines (96-98): Trajan's correspondence with Pliny, indicates first authorization of persecution against Christians. Christianity declared to be a "religio illicita." "One who is a Christian must be punished." Martyrdom of Ignatius and of Simeon, 2nd B. of Jerusalem. Hadrian's rescript - "It is unjust to kill Christians without a regular indictment and a trial." Jerome (c. 400) says a "gravissimam persecutionem" but we know of only one martyr, Telesphorus, 7th B. of Rome. More repression under Antoninus Pious. 3 advisors: Fronto, Munatius Felix, Lollius Urbicus. Fronto's oration against the Christians. Internally the Christians in Rome experiencinig discord (Marcion, Gnostics, Valentinus). C. 150 Justin writes I Apology. Sporadic persecution. Polycarp 156. /~\

“Marcus Aurelius (161-180) actively persecuted. Justin martyred. A loyalty oath was introduced. Some Christians to the mines. Story of the Thundering Legion. Melito of Sardes. Athenagoras. Lvons and Vienne in 177. Tatian's 'Address' attacked Rome. Celsus 177-180. Martyrs of Scilli in North Africa 180. Commodus' mistress, Marcia, was a Christian and gained toleration. /~\

“Severi (193-211): Tertullian's Apology c. 197. Martyrdom of Perpetua and Felicity. Decree 201 against Jews or Xians making converts. Local and sporadic persecution. Origen's father d. Christians in emperor's household. Tutor of Caracalla was a Christian. No persecution under Caracalla or Alexander. Alex put statue of Christ in imperial chapel. Peace for 25 years. Christians have use of burial sites. Origen was invited by Julia Mammae (emperor's mother) to visit. /~\

“Anarchy (235-285) In 50 years there were 26 emperors, all but one dying violent deaths. Maximimus (235) persecuted. Origen writes "To The Martyrs" Philip the Arabian (244-249) was said to be a Christian. He and his wife exchanged letters with Origen. Decius (249-251) 1st universal persecution of all Christians. (Xian sources refer to him as 'damned animal') All inhabitants sacrifice and receive certificate ('libelli'). Schism in church. Cyprian. Origen tortured. Valerian (251-260) two edicts. Last one death to all clergy, loss of property and rights to citizens, women become slaves. Cyprian died. Gallienus (260-268) Edict of Toleration. Xians own property and worship freely. Aurelian (270-275) against Paul of Samosata, only churches in agreement with Rome are orthodox./~\

“Diocletian and Galerius (284-305): Prompted by Galerius, a systematic and thorough persecution. Four edicts, successively more severe. Probably the worst of all ancient persecutions. Diocl own wife and daughter were Christians but forced to recant. In 305 Diocletian abdicated. There follows a struggle for power which does not end until Constantine is successful in 312 (West) and 324 (East). In 311 Galerius issues an edict of toleration. In 313 Constantine's 'Edict of Milan' ends ancient persecutions.. /~\

Christian Participation in Pagan Culture

Agape feast

Professor Wayne A. Meeks told PBS: “When we hear of pagans claiming that Christians are kind of antisocial -- "haters of humanity" is the terminology that the pagans themselves would have used -- what they're really referring to is the unwillingness of Christians at various times to participate in some of the most common aspects of the religious life of cities. We have to remember that religion in the ancient world is very much a part of public life. They had no idea of a separation of religion and state. Indeed quite the opposite. Religion was one of the most important features of the maintenance of the state. [Source: Wayne A. Meeks, Woolsey Professor of Biblical Studies Yale University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

“One offered sacrifices on certain days as a part of the celebration of the founding of the state. One offered sacrifices on the birthday of the emperor. Cities very often mounted these enormous celebrations to celebrate the emperors and all the populace would have been expected to come and join in and for most people you wanted to join in. After all, this would have been a public celebration. A great festival.... Better yet, the aristocracy was paying for it. The city magistrates were the ones who were paying for the food and the celebrations and if you were a common member of the city, you could just go and enjoy yourself. For a lot of the lower classes it's probably the case that this was the only time that they got to eat certain kinds of food. The sacrifices that were offered in the temples were often then distributed as picnic baskets for the people. So on these kinds of festival days to go and participate was one of the important things to do.

“It's in this context in all probability that some of the antipathy toward Christianity began to develop, precisely because the Christians wouldn't go and participate. They didn't want to go to the temples and celebrate the birthday of the emperor. They didn't want to take the food that had been sacrificed to the pagan Gods home and eat it at their dinner tables because to do so might have put them in the position of participating in the very idolatry that their religion could not condone.

Christian Appropriation of Pagan Symbols

Professor Wayne A. Meeks told PBS: “The integration of Christian intellectual and religious life into the Roman world can be seen in a number of different ways: their participation in social life, their participation increasingly in public activities, but it can also be seen in some of the smaller and more intimate symbols of Christian identity that one begins to find in the Roman world. Two of the most important artistic symbols that we find are the good shepherd and the orans or the standing figure in the position of prayer that we see so prominently in the catacombs. ... [Source: Wayne A. Meeks, Woolsey Professor of Biblical Studies Yale University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“[W]hat is very important to recognize is that both of these symbols are actually old pagan symbols that had been around in the Roman world for quite some time, and in fact even within the catacombs it's very difficult to tell sometimes when one of these paintings is Christian or pagan, so that while we have this figure of the shepherd with the sheep draped over his shoulders or standing dutifully at his feet, we now may tend to think of that as reflecting the gospel stories of Jesus of the lost sheep or Jesus as the good shepherd from the Gospel of John. In point of fact, from Roman perspective, this is the virtue of philanthropy, of love of humanity, and it's one of the most important virtues of Roman civic and public life.

“The Christians seem to take it over very readily and apply it to the gospel virtues as well. In the case of the orans figure..., this is the old pagan virtue of piety, of loyalty to the state, and so the person standing with eyes up cast toward heaven and hands in a gesture of appeal to the gods could have been seen by a pagan as a sign of loyalty to the state, loyalty to the old gods. To the Christians it becomes loyalty to the God of Jesus Christ.”

Loyalty to Christ Versus Loyalty to Caesar

Professor L. Michael White told PBS: “By the second century when Christianity is becoming a recognizable force in the Roman Empire there are some lingering political questions still attached to it. We have to remember that it was known that Jesus was executed as a political criminal and the gospel traditions themselves preserved this tradition of Pilate questioning Jesus. "Are you a king? Are you King of the Jews?" Now whether or not Pilate ever really asked that question of Jesus directly it does appear to be the case ... that Jesus claimed to be a king. A kind of Messianic claimant, "King of the Jews" was attached to his cross. That tradition, that legacy while it was a very important part of Christian confession and tradition also opened up another door of problems with regard to the Roman Empire because if somehow Christ was their king, it called into question their loyalty to the king, that is, the emperor of the Roman state. We have a case of kings and kingdoms in conflict. The old apocalyptic imagery of coming kingdom of God, of a coming Messiah from heaven, could be read as a prominent denunciation of the Roman Empire and of its king, Caesar. [Source: L. Michael White, Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Caesar's deification

“The Christian tradition seems to be ambivalent toward the Roman state at certain times. We have this apocalyptic tradition that seems to have an implicit criticism of the state and indeed some lingering portions of the apocalyptic tradition within Christianity continued to be very antagonistic toward the Roman Empire and the imperial state structures. The Book of Revelation, or the apocalypse as it's known within the New Testament documents, is a very strong denunciation of the state. Here the emperor and the imperial court are portrayed as a dragon who goes out to devour the Virgin Mother of a heavenly child. There's no way of reading this other than an absolute polemic against the beastly nature of the empire over against the spiritual nature of the Christian church, and in this tradition it is also clear what God has in mind for the future.... In the Book of Revelation the future plan of God has a very clear and definite ending. Rome will be thrown down. The church will survive in triumph. This is the legacy of apocalypse that we still see in certain brands of Christianity.

“On the other side we find Christians saying just the opposite, that the emperor and governors and the state as a whole are ordained by God and one should be respectful of the state and its municipal offices. Certain Christians seem to go way out of their way to avoid persecution, and not only avoid persecution but avoid being viewed as disloyal to the state. Paul himself seems to say this in Romans 13 .... By the second and third century, Christians will still be claiming we're loyal to the state. "We're not bad citizens. We're not doing anything wrong. Look at what we do. Look at what we teach. Look at how... what we practice. Look are our ethics and you'll see we're just as good citizen[s] as you."

“So what we see at this time is that the Christians really are [in] kind of an ambivalent state within the Roman Empire. They haven't really found their place yet, and occasionally Christians are blamed for catastrophes that obviously were none of their doing at all. ...[T]here's a wonderful quote from the Christian writer, Tertullian. He's a kind of satirical fellow all the way and he says, "Does the Nile River not rise high enough? Are there plagues and floods and famines? All at once the cry goes up from all the neighbors. Christians to the lion! Christians to the lion!" and then he turns with his sharp satirical eye and says, "What, all those Christians to one lion?"

Mithraism and Christianity

Mithraism was a forerunner, competitor and contemporary of early Christianity even though the two religions had little to say about each other. Mithraism was described by the Gnostic heretic Origen, and St. Jerome, the church Father, and was noted by many historians as having similarities to Christianity.

Mithras sun god Sol Invictus

Mithraism was one of best known foreign cults in the late Roman Empire. Professor Roger Beck of the University of Toronto Mississauga wrote for the BBC: “The Mithraists were worshippers of the ‘Unconquered Sun God Mithras’, as the inscriptions call him. We know a good deal about them because archaeology has disinterred many meeting places together with numerous artifacts and representations of the cult myth, mostly in the form of relief sculpture. “From this evidence we know that the cult was the last of the important mystery cults to evolve and that it thrived in the second and third centuries A.D. and waned in the fourth as élite patronage was gradually transferred to Christianity. [Source: Professor Roger Beck, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Unlike the public rituals and processions dedicated to Cybele and Isis in Imperial Rome, the worship of Mithras was secret and mysterious. At the end of the first century A.D., the Iranian god Mithras, creator and protector of animal and plant life, began to appear in Italy, becoming especially popular with Roman legionaries, imperial slaves, and ex-slaves. Not limited to the class of soldiers, however, Mithraists could also be found in the circles of the imperial households. In the absence of Mithraic literature, evidence of the cult, its rituals, and customs comes from archaeological finds and depictions of the god.” [Source: Claudia Moser, Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

L. Michael White of the University of Texas at Austin told PBS: “Mithraism, like “Christianity, was a rather late arriving religion in the Roman empire. We don't really hear much about the Mithras cult before the second century about the same time that Pliny starts to recognize Christians. But by the end of the second century there are Mithraic chapels. .... Mithraic chapels spread throughout most of the major cities, especially in the Western part of the empire. [Source: L. Michael White, Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MITHRAISM: MITHRAS, PERSIA, CHRISTIANITY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MITHRAISM BELIEFS, WORSHIP, INITIATIONS, TEMPLES AND BULL RITUALS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CULTS IN THE GREEK AND ROMAN WORLD europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MAGNA MATER (CYBELE) CULTS: ATTIS, SELF-CASTRATED PRIESTS, BULL SACRIFICE europe.factsanddetails.com

‘Triumph’ of Christianity?

Dr Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe wrote for the BBC: “Contemporary Christians treated Constantine’s conversion as a decisive moment of victory in a cosmic battle between good and evil, even as the end of history, but it was far from that. Christianity did increase in numbers gradually over the next two centuries, and among Constantine’s successors only one,the emperor Julian in the 360s AD, mounted concerted action to re-instate paganism as the dominant religion in the empire. “But there was no ‘triumph’, no one moment where Christians had visibly ‘won’ some battle against pagans. Progress was bitty, hesitant, geographically patchy. [Source: Dr Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Christianity offered spiritual comfort and the prospect of salvation on the one hand, and attractive new career paths and even riches as a worldly bishop on the other. But plenty of pagans, both aristocrats based in the large cities of the empire and rural folk, remained staunch in their adherence to an old faith. |Some hundred years after Constantine’s ‘conversion’, Christianity seemed to be entrenched as the established religion, sponsored by emperors and protected in law. But this did not mean that paganism had disappeared. |::|

“Indeed, when pagans blamed Christian impiety (meaning negligence of the old gods) for the barbarian sack of Rome in 410 AD, one of the foremost Christian intellectuals of the time, Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, regarded the charge as serious enough to warrant lengthy reply in his mammoth book 'The City of God'. Paganism may have been effectively eclipsed as an imperial religion, but it continued to pose a powerful political and religious challenge to the Christian church. |::|

Christianity and the Fall of the Roman Empire

early church in Ostia Antica, Italy

Edward Gibbon wrote in “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”: “As the happiness of a future life is the great object of religion, we may hear, without surprise or scandal, that the introduction, or at least the abuse, of Christianity had some influence on the decline and fall of the Roman empire. The clergy successfully preached the doctrines of patience and pusillanimity; the active virtues of society were discouraged; and the last remains of the military spirit were buried in the cloister; a large portion of public and private wealth was consecrated to the specious demands of charity and devotion; and the soldiers' pay was lavished on the useless multitudes of both sexes, who could only plead the merits of abstinence and chastity. [Source: Edward Gibbon: General Observations on the Fall of the Roman Empire in the West from “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” Chapter 38, published 1776]

“Faith, zeal, curiosity, and the more earthly passions of malice and ambition kindled the flame of theological discord; the church, and even the state, were distracted by religious factions, whose conflicts were sometimes bloody, and always implacable; the attention of the emperors was diverted from camps to synods; the Roman world was oppressed by a new species of tyranny; and the persecuted sects became the secret enemies of their country. Yet party-spirit, however pernicious or absurd, is a principle of union as well as of dissension. The bishops, from eighteen hundred pulpits, inculcated the duty of passive obedience to a lawful and orthodox sovereign; their frequent assemblies, and perpetual correspondence, maintained the communion of distant churches: and the benevolent temper of the gospel was strengthened, though confined, by the spiritual alliance of the Catholics. The sacred indolence of the monks was devoutly embraced by a servile and effeminate age; but, if superstition had not afforded a decent retreat, the same vices would have tempted the unworthy Romans to desert, from baser motives, the standard of the republic. Religious precepts are easily obeyed, which indulge and sanctify the natural inclinations of their votaries; but the pure and genuine influence of Christianity may be traced in its beneficial, though imperfect, effects on the Barbarian proselytes of the North. If the decline of the Roman empire was hastened by the conversion of Constantine, his victorious religion broke the violence of the fall, and mollified the ferocious temper of the conquerors.

“This awful revolution may be usefully applied to the instruction of the present age. It is the duty of a patriot to prefer and promote the exclusive interest and glory of his native country; but a philosopher may be permitted to enlarge his views, and to consider Europe as one great republic, whose various inhabitants have attained almost the same level of politeness and cultivation. The balance of power will continue to fluctuate, and the prosperity of our own or the neighbouring kingdoms may be alternately exalted or depressed; but these partial events cannot essentially injure our general state of happiness, the system of arts, and laws, and manners, which so advantageously distinguish, above the rest of mankind, the Europeans and their colonies. The savage nations of the globe are the common enemies of civilized society; and we may inquire with anxious curiosity, whether Europe is still threatened with a repetition of those calamities which formerly oppressed the arms and institutions of Rome. Perhaps the same reflections will illustrate the fall of that mighty empire, and explain the probable causes of our actual security.”

Roman Laws and Christianity

Edward Gibbon wrote in “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”: “A new spirit of legislation, respectable even in its error, arose in the empire with the religion of Constantine. The laws of Moses were received as the divine original of justice, and the Christian princes adapted their penal statutes to the degrees of moral and religious turpitude. Adultery was first declared to be a capital offence: the frailty of the sexes was assimilated to poison or assassination, to sorcery or parricide; the same penalties were inflicted on the passive and active guilt of paederasty; and all criminals of free or servile condition were either drowned or beheaded, or cast alive into the avenging flames.[Source: Chapter XLIV: Idea Of The Roman Jurisprudence. Part VII,“Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” Vol. 4, by Edward Gibbon, 1788, sacred-texts.com]

The adulterers were spared by the common sympathy of mankind; but the lovers of their own sex were pursued by general and pious indignation: the impure manners of Greece still prevailed in the cities of Asia, and every vice was fomented by the celibacy of the monks and clergy. Justinian relaxed the punishment at least of female infidelity: the guilty spouse was only condemned to solitude and penance, and at the end of two years she might be recalled to the arms of a forgiving husband.

early church in Salona, Greece

But the same emperor declared himself the implacable enemy of unmanly lust, and the cruelty of his persecution can scarcely be excused by the purity of his motives. In defiance of every principle of justice, he stretched to past as well as future offences the operations of his edicts, with the previous allowance of a short respite for confession and pardon. A painful death was inflicted by the amputation of the sinful instrument, or the insertion of sharp reeds into the pores and tubes of most exquisite sensibility; and Justinian defended the propriety of the execution, since the criminals would have lost their hands, had they been convicted of sacrilege.

In this state of disgrace and agony, two bishops, Isaiah of Rhodes and Alexander of Diospolis, were dragged through the streets of Constantinople, while their brethren were admonished, by the voice of a crier, to observe this awful lesson, and not to pollute the sanctity of their character. Perhaps these prelates were innocent. A sentence of death and infamy was often founded on the slight and suspicious evidence of a child or a servant: the guilt of the green faction, of the rich, and of the enemies of Theodora, was presumed by the judges, and paederasty became the crime of those to whom no crime could be imputed. A French philosopher has dared to remark that whatever is secret must be doubtful, and that our natural horror of vice may be abused as an engine of tyranny. But the favorable persuasion of the same writer, that a legislator may confide in the taste and reason of mankind, is impeached by the unwelcome discovery of the antiquity and extent of the disease.

“The penal statutes form a very small proportion of the sixty-two books of the Code and Pandects; and in all judicial proceedings, the life or death of a citizen is determined with less caution or delay than the most ordinary question of covenant or inheritance. This singular distinction, though something may be allowed for the urgent necessity of defending the peace of society, is derived from the nature of criminal and civil jurisprudence. Our duties to the state are simple and uniform: the law by which he is condemned is inscribed not only on brass or marble, but on the conscience of the offender, and his guilt is commonly proved by the testimony of a single fact. But our relations to each other are various and infinite; our obligations are created, annulled, and modified, by injuries, benefits, and promises; and the interpretation of voluntary contracts and testaments, which are often dictated by fraud or ignorance, affords a long and laborious exercise to the sagacity of the judge. The business of life is multiplied by the extent of commerce and dominion, and the residence of the parties in the distant provinces of an empire is productive of doubt, delay, and inevitable appeals from the local to the supreme magistrate. Justinian, the Greek emperor of Constantinople and the East, was the legal successor of the Latin shepherd who had planted a colony on the banks of the Tyber. In a period of thirteen hundred years, the laws had reluctantly followed the changes of government and manners; and the laudable desire of conciliating ancient names with recent institutions destroyed the harmony, and swelled the magnitude, of the obscure and irregular system. The laws which excuse, on any occasions, the ignorance of their subjects, confess their own imperfections:

the civil jurisprudence, as it was abridged by Justinian, still continued a mysterious science, and a profitable trade, and the innate perplexity of the study was involved in tenfold darkness by the private industry of the practitioners. The expense of the pursuit sometimes exceeded the value of the prize, and the fairest rights were abandoned by the poverty or prudence of the claimants. Such costly justice might tend to abate the spirit of litigation, but the unequal pressure serves only to increase the influence of the rich, and to aggravate the misery of the poor. By these dilatory and expensive proceedings, the wealthy pleader obtains a more certain advantage than he could hope from the accidental corruption of his judge. The experience of an abuse, from which our own age and country are not perfectly exempt, may sometimes provoke a generous indignation, and extort the hasty wish of exchanging our elaborate jurisprudence for the simple and summary decrees of a Turkish cadhi. Our calmer reflection will suggest, that such forms and delays are necessary to guard the person and property of the citizen; that the discretion of the judge is the first engine of tyranny; and that the laws of a free people should foresee and determine every question that may probably arise in the exercise of power and the transactions of industry. But the government of Justinian united the evils of liberty and servitude; and the Romans were oppressed at the same time by the multiplicity of their laws and the arbitrary will of their master. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024