Home | Category: Religion and Gods

RELIGION IN IMPERIAL ROME

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: Roman practices were celebrated in certain specific contexts throughout the Empire. Roman coloniae, settlements consisting of Roman citizens (ex-soldiers and landless poor from Rome), were established in the provinces in the late Republic and early Empire. Such settlements were privileged clones of Rome in a sea of mere subjects of Rome. Their public religious life had a strongly Roman cast, despite much variation from place to place. Many coloniae had their own Capitolium, priesthoods (pontifices and augures), and rituals based on those of Rome. [Source: Arnaldo Momigliano (1987), Simon Price (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

The Roman army also followed overtly Roman rules. Military camps had at their center a building that housed the legionary standards and imperial and divine images (sometimes including images of Romulus and Remus). The importance of the building is reflected in the fact that in 208 ce it is even called a Capitolium. From the early Empire all legionary soldiers (who were Roman citizens) and later all auxiliary soldiers (who were originally not Roman citizens) celebrated religious festivals modeled on those of Rome. They celebrated festivals on the Roman cycle (e.g. Vestalia or Neptunalia); they performed imperial vows to the Capitoline triad on January 3; and they celebrated imperial birthdays and other events.

Towns with the status of municipia (where local citizens had the so-called Latin right and some even full Roman citizenship) shared some of the Roman religious features of coloniae ; their principal priesthoods, for example, were named after and modeled on Roman institutions — pontifices, augures, and haruspices. And from the second century ce onward, municipia in North Africa also began to build their own Capitolia. Overtly Roman practices served as part of the process of competitive emulation that marked civic life in many parts of the Empire. The original Caesarian regulations for the colonia of Urso in southern Spain, which constitute our fullest single document of this process, remained sufficiently important to Urso for them to be reinscribed a hundred years later, at a time when other Spanish communities had just received the (lesser) status of the Latin right (Crawford, 1996, pp. 393-454).

Throughout the Empire, whatever the technical status of the community, there were publicly organized and celebrated religious rites. For example, the Greek city of Ephesus (Gr., Ephesos) proudly commemorated the fact that Artemis was born at Ephesus and voted to extend the period of her festival "since the god Artemis, patron of our city, is honored not only in her native city, which she has made more famous than all other cities through her own divinity, but also by Greeks and barbarians, so that everywhere sanctuaries and precincts are consecrated for her, temples are dedicated and altars set up for her, on account of her manifest epiphanies". Individuals took part in such festivals and also sacrificed incense on small altars outside their houses when processions in honor of the Roman emperor passed by. This is not to say that piety towards the gods existed only in public contexts or indeed was constituted primarily through civic channels. Individuals formed private religious associations, either simply to worship a particular deity or to form a society that would ensure the proper burial of its members. They also made private prayers and vows to the appropriate god and set up votive offerings to the god in his or her sanctuary.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Religion in the Roman Empire” by James B. Rives Amazon.com;

“Religions of Rome: Volume 1: A History” by Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price ( Amazon.com;

“Religions of Rome: Volume 2: A Sourcebook” by Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price ( Amazon.com;

“The Economy of Roman Religion” by Andrew Wilson , Nick Ray, et al. (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Dancing Lares and the Serpent in the Garden: Religion at the Roman Street Corner” by Harriet I. Flower (2017) Amazon.com;

"Roman Myths: Gods, Heroes, Villains and Legends of Ancient Rome” by Martin J Dougherty (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“Household Gods: Private Devotion in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Alexandra Sofroniew (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Religion of the Etruscans” by Nancy Thomson de Grummond, Erika Simon (2006) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Animal Sacrifice: Ancient Victims, Modern Observers”

by Christopher A. Faraone and F. S. Naiden (2012) Amazon.com;

“Magic and Religion in the Ancient Mediterranean World” by Radcliffe G. Edmonds III and Carolina López-Ruiz (2023) Amazon.com

“Pagans and Christians” by Robin Lane Fox (1986) Amazon.com

“Religion in Roman Egypt” by David Frankfurter (2000) Amazon.com;

“Mystery Cults in the Ancient World” by Hugh Bowden (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Secret Sacred: Mystery Cults in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Damien Stone (2025) Amazon.com;

“Isis: The Eternal Goddess of Egypt and Rome” by Lesley Jackson (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Religion of the Mithras Cult in the Roman Empire: Mysteries of the Unconquered” by Roger Beck Amazon.com;

“Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia” by C. M. C. Green (2007) Amazon.com;

Changes in Religion in the Roman Empire

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: The Roman state's extraordinary and unexpected transformation from one that had hegemony over the greater part of Italy into a world state in the second and first centuries B.C. had implications for Roman religion that are not easy to grasp. After all, Christianity, a religion wholly "foreign" in its origins, arose from this period of Roman ascendancy. To begin, then, to understand the religious system of imperial Rome, it is best to confine the discussion to some elementary and obviously related facts. [Source: Arnaldo Momigliano (1987), Simon Price (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

First, the old Roman practice of inviting the chief gods of their enemies to become gods of Rome (evocatio) played little part in the new stage of imperialism. Evocatio played some role in Rome's conquests in the middle Republic, but the practice had been transformed. The last temple to be built in Rome to house a deity "evoked" from an enemy of Rome was that of Vortumnus (264 B.C.). A version of the ritual was probably used to "evoke" the Juno of Carthage in the 140s B.C., but no temple was built to her in Rome. The extent of the transformation is shown by the fact that in 75 B.C. a Roman conqueror of Isaura Vetus (in Asia Minor) took a vow (in language reminiscent of the evocatio), which seems to have resulted in the foundation of a new local cult of the patron deity of Isaura Vetus. The old procedures of evocatio are not found in the imperial period. Instead, the cults of Rome's subjects continued to form the basis for their local religious system.

Second, while it was conquering the Hellenistic world, Rome was involved in a massive absorption of Greek language, literature, and religion, with the consequence that the Roman gods became victorious over those of Greece while their old identification with Greek gods became more firmly established. Because the gods were expected to take sides and to favor their own worshipers, this could have created some problems. In fact, from the middle Republic onward, the Romans respected the gods of the Greeks. As early as 193 B.C. the Romans replied to the city of Teos (in Asia Minor) that they would "seek to improve both honors towards the god [Dionysos, the patron deity of Teos] and privileges towards you," on the grounds that Roman success was due to her well-known reverence towards the gods (Sherk, 1969, pp. 214–216). In other words, the Romans accepted that the Greek god Dionysos was included among the gods that favored Rome. In consequence, the Greeks felt no pressure to modify their ancestral cults, and traditional Greek cults remained vibrant throughout the imperial period.

Third, the conquest of Africa, Spain, and Gaul produced the opposite phenomenon of a large, though by no means systematic, identification of Punic, Iberian, and Celtic gods with Roman gods. This, in turn, is connected with two opposite aspects of the Roman conquest of the West. On the one hand, the Romans had little sympathy and understanding for the religion of their Western subjects. Although occasionally guilty of human sacrifice, they found the various forms of human sacrifices that were practiced more frequently in Africa, Spain, and Gaul repugnant (hence their later efforts to eliminate the Druids in Gaul and in Britain). On the other hand, northern Africa (outside Egypt) and western Europe were deeply Latinized in language and Romanized in institutions, thereby creating the conditions for the assimilation of native gods to Roman gods.

Yet the Mars, the Mercurius, and even the Jupiter and the Diana seen so frequently in Gaul under the Romans are not exactly the same as in Rome. The individuality of the Celtic equivalent of Mercurius has already been neatly noted by Caesar (Gallic War 6.17). Some Roman gods, such as Janus and Quirinus, do not seem to have penetrated Gaul. Similarly, in Africa, Saturnus preserved much of the Baal Hammon with whom he was identified. There, Juno Caelestis (or simply Caelestis, destined to considerable veneration outside Africa) is Tanit (Tinnit), the female companion of Baal Hammon. The assimilation of the native god is often revealed by an accompanying adjective (in Gaul, for example, Mars Lenus and Mercurius Dumiatis). An analogous phenomenon had occurred in the East under the Hellenistic monarchies: native, especially Semitic, gods were assimilated to Greek gods, especially to Zeus and Apollo. The Eastern assimilation went on under Roman rule (as seen, for example, with Zeus Panamaros in Caria).

Roman soldiers, who became increasingly professional and lived among natives for long periods of time, played a part in these syncretic tendencies. A further consequence of imperialism was the emphasis on Victory and on certain gods of Greek origin (such as Herakles and Apollo) as gods of victory. Victoria was already recognized as a goddess during the Samnite Wars; she was later associated with various leaders, from Scipio Africanus to Sulla and Pompey. Roman emperors used an elaborate religious language in their discussions of Victory. Among Christians, Augustine of Hippo depicted Victory as God's angel (City of God 4.17).

These transformations are part of the changing relationship between the center (Rome) and the periphery (the Empire). By the early Empire, Italy fell wholly under the authority of Rome: in 22 ce the senate decided that "all rituals, temples, and images of the gods in Italian towns fall under Roman law and jurisdiction" (Tacitus, Annals 3.71). The provinces were different and not subject to Roman jurisdiction in the same way. However, Roman governors of the imperial period were required to watch over religious life in their province. They were concerned that religious life proceed in an orderly and acceptable manner, and the governors' official instructions included the order to preserve sacred places. They also ensured that the provincials took part in the annual performance on January 3 of the Roman ritual vows of allegiance to the emperor and the Empire.

Imperial Cult in Ancient Rome

Augustus

Dr Neil Faulkner wrote for the BBC: “This concept, of a tough but essentially benevolent imperial power, was embodied in the person of the emperor. His presence was felt everywhere. His statues dominated public places. He was worshipped alongside Jupiter and the military standards in frontier forts, and in the sanctuaries of the imperial cult in provincial towns. His image was stamped on every coin, and thus reached the most remote corners of his domain - for there is hardly a Roman site, however rude, where archaeologists do not find coins. The message was clear: thanks to the leadership of the emperor we can all go safely about our business and prosper. [Source: Dr Neil Faulkner, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“How did the spin-doctors of ancient Rome represent the great leader to his people? Sometimes, wearing cuirass and a face of grim determination, he was depicted as a warrior and a general; an intimidating implicit reference to global conquest and military dictatorship. At other times, he wore the toga of a Roman gentleman, as if being seen in the law-courts, making sacrifice at the temple, or receiving guests at a grand dinner party at home. In this guise, he was the paternalistic 'father of his country', the benevolent statesman, the great protector. |::|

Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “The cult of the emperors developed naturally enough from the time of the deification of Julius Caesar. The movement for this deification was of Oriental origin. The Genius of the emperor was worshiped as the Genius of the father had been worshiped in the household. The cult, beginning in the East, was then established in the western provinces and finally in Italy. It was under the care of the seviri Augustales in the municipalities. The worship of the emperor in his lifetime was not permitted at Rome, but spread through the provinces, taking the place of the old state religion. It was this that caused the opposition to Christianity, for the refusal of the Christians to take part was treasonable. Their offense was political, not religious. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

A sculpted relief from the base of the column of the emperor Antoninus Pius, dated to A.D. 161, shows the apotheosis (transformation into gods) of Antoninus Pius and his wife Faustina. “They are shown by the portrait busts at the top of the frame, flanked by eagles - associated with imperial power and Jupiter - and were typically released during imperial funerals to represent the spirits of the deceased. Antoninus and Faustina are being carried into the heavens by a winged, heroically nude figure. The armoured female figure on the right is the goddess Roma, a divine personification of Rome, and the reclining figure to the left - with the obelisk - is probably a personification of the Field of Mars in Rome, where imperial funerals took place. [Source: BBC]

See Separate Article: STATE RELIGION IN ANCIENT ROME: IMPERIAL CULT AND EMPEROR WORSHIP europe.factsanddetails.com

Imperial Cult and Revival of Old State Cults by Augustus

According to Encyclopedia.com Octavian began a systematic revival of the old state cults in the years before Actium (31), and then, as Augustus, founder of the Principate, he carried out this policy on a much wider scale. He instituted the Ludi saeculares in 17 B.C., and in 12 B.C., after the death of Lepidus, he assumed the office of Pontifex Maximus — held subsequently by all his successors until it was relinquished by Gratian, A.D. 382. He rebuilt temples throughout Rome, restored the old priesthoods, and required them to celebrate the rituals of their respective cults with the earlier regularity and pomp. He enlisted the help also of the great contemporary poets Horace, Virgil, and Ovid in his program of restoring the Old Roman cults and their celebration. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

But the most important of his religious innovations was the imperial cult. It was in part Hellenistic, but the emphasis on the public worship of the Genius of the emperor, especially in Rome and Italy, gave it a Roman character as well. It was intended to serve as an effective symbol of unity in the universal empire of Rome and also to promote a deeper loyalty on the part of the army to its imperator, or commander in chief. Gradually, the imperial cult and its priesthoods lost much of their appeal, but they enjoyed a marked revival in the period from Aurelian to Diocletian. Under the influence of the central administration and the model set by Rome, the religious cults of the Roman provinces, despite local aspects, assumed more and more the Roman pattern, at least in external form.

RELATED ARTICLES: AUGUSTUS AS EMPEROR OF ROME: GOVERNING STYLE, WORSHIP, ADMINISTRATION europe.factsanddetails.com ; Also See Temple Building Under AUGUSTUS'S ACCOMPLISHMENTS: BUILDING CAMPAIGN, PUBLIC WORKS, THE ARTS europe.factsanddetails.com

Imperial Uses of Religion in the Roman Empire

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: Augustus and his contemporaries thought, or perhaps in some cases wanted other people to think, that the preceding age (roughly the period from the Gracchi to Caesar) had seen a decline in the ancient Roman care for gods. Augustus himself stated in the public record known as the Res gestae that he had restored eighty-two temples and shrines (in one year, 28 B.C.). He revived cults and religious associations, such as the Arval Brothers and the fraternity of the Titii, and appointed a flamen dialis, a priestly office that had been left vacant since 87 B.C. This revivalist feeling was not entirely new: it was behind the enormous collection of evidence concerning ancient Roman cults, the "divine antiquities," that Varro had dedicated to Caesar about 47 B.C. in his Antiquitatum rerum humanarum et divinarum libri ; the rest of the work, the "human antiquities," was devoted to Roman political institutions and customs. Varro's work codified Roman religion for succeeding generations, and as such it was used for polemical purposes by Christian apologists. [Source: Arnaldo Momigliano (1987), Simon Price (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

Temple of Augustus in Barcelona

The Romans also turned certain gods of Greek origin into gods of victory. As early as 145 B.C., L. Mummius dedicated a temple to Hercules Victor after his triumph over Greece. After a victory, generals often offered 10 percent of their booty to Hercules, and Hercules Invictus was a favorite god of Pompey. Apollo was connected with Victory as early as 212 B.C. Caesar boosted her ancestress Venus in the form of Venus Victrix. But it was Apollo who helped Octavian, the future Augustus, to win the Battle of Actium in September of 31 B.C.

It is difficult to do justice both to the mood of the Augustan restoration and to the unquestionable seriousness with which the political and military leaders of the previous century tried to support their unusual adventures by unusual religious attitudes. Marius, a devotee of the Mater Magna (Cybele), was accompanied in his campaigns by a Syrian prophetess. Sulla apparently brought from Cappadocia the goddess Ma, soon identified with Bellona, whose orgiastic and prophetic cult had wide appeal. Furthermore, he developed a personal devotion to Venus and Fortuna and set an example for Caesar, who claimed Venus as the ancestress of the gens Julia. As pontifex maximus for twenty years, Caesar reformed not only individual cults but also the calendar, which had great religious significance. He tried to support his claim to dictatorial powers by collecting religious honors that, though obscure in detail and debated by modern scholars, anticipate later imperial cults.

Unusual religious attitudes were not confined to leaders. A Roman senator, Nigidius Figulus, made religious combinations of his own both in his writings and in his practice: magic, astrology, and Pythagoreanism were some of the ingredients. Cicero, above all, epitomized the search of educated men of the first century B.C. for the right balance between respect for the ancestral cults and the requirements of philosophy. Cicero could no longer believe in traditional divination. When his daughter died in 45 B.C., he embarked briefly on a project for making her divine. This was no less typical of the age than the attempt by Clodius in 62 B.C. to desecrate the festival of Bona Dea, reserved for women, in order to contact Caesar's wife (he escaped punishment).

Handover of Sacred Law From the Senate to the Emperor

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: The imperial age inclined toward distinctions and compromises. The Roman pontifex maximus Q. Mucius Scaevola (early first century B.C.) is credited with the popularization of the distinction, originally Greek, between the gods of the poets as represented in myths, the gods of ordinary people to be found in cults and sacred laws, and finally the gods of the philosophers, confined to books and private discussion. It was the distinction underlying the thought of Varro and Cicero. No wonder, therefore, that in that atmosphere of civil wars and personal hatreds, cultic rules and practices were exploited ruthlessly to embarrass enemies, and no one could publicly challenge the ultimate validity of traditional practices. [Source: Arnaldo Momigliano (1987), Simon Price (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

The Augustan restoration discouraged philosophical speculation about the nature of the gods: Lucretius's De rerum natura remains characteristic of the age of Caesar. Augustan poets (Horace, Tibullus, Propertius, and Ovid) evoked obsolescent rites and emphasized piety. Virgil interpreted the Roman past in religious terms. Nevertheless, the combined effect of the initiatives of Caesar and Augustus amounted to a new religious situation.

For centuries the aristocracy in Rome had controlled what was called ius sacrum (sacred law), the religious aspect of Roman life, but the association of priesthood with political magistracy, though frequent and obviously convenient, had never been institutionalized. In 27 B.C. the assumption by Octavian of the name Augustus implied, though not very clearly, permanent approval of the gods (augustus may connote a holder of permanent favorable auspices). In 12 B.C. Augustus assumed the position of pontifex maximus, which became permanently associated with the figure of the emperor (imperator), the new head for life of the Roman state. Augustus's new role resulted in an identification of religious with political power, which had not existed in Rome since at least the end of the monarchy. Furthermore, the divinization of Caesar after his death had made Augustus, as his adopted son, the son of a divus. In turn, Augustus was officially divinized (apotheosis) after his death by the Roman Senate.

Divinization after death did not become automatic for his successors (Tiberius, Gaius, and Nero were not divinized); nevertheless, Augustus's divinization created a presumption that there was a divine component in an ordinary emperor who had not misbehaved in his lifetime. Divinization also reinforced the trend toward the cult of the living emperor, which had been most obvious during Augustus's life. With the Flavian dynasty and later with the Antonines, it was normal for the head of the Roman state to be both the head of the state religion and a potential, or even actual, god.

As the head of Roman religion, the Roman emperor was therefore in the paradoxical situation of being responsible not only for relations between the Roman state and the gods but also for a fair assessment of his own qualifications to be considered a god, if not after his life, at least while he was alive. This situation, however, must not be assumed to have applied universally. Much of the religious life in individual towns was in the hands of local authorities or simply left to private initiative. The financial support for public cults was in any case very complex, but many sanctuaries (especially in the Greek world) had their own sources of revenue. It will be enough to mention that the Roman state granted or confirmed to certain gods in certain sanctuaries the right to receive legacies (Ulpian, Regulae 22.6). In providing a local shrine with special access to money, an emperor implied no more than benevolence toward the city or group involved.

Magic and Divination in the Roman Empire

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: A striking development of the imperial period was that the concept of magic emerged as the ultimate superstition, a system whose principles were parodic of and in opposition to true religio. According to the encyclopedia of Pliny the Elder, magic, which originated in Persia, was a heady combination of medicine, religion, and astrology that met human desires for health, control of the gods, and knowledge of the future. The system was, in his view, totally fraudulent (Natural History 30.1-18; cf. Lucan's Pharsalia 6.413-830). Such views of magic as a form of deviant religious behavior should also be related to the developing concepts and practices of Roman law in the imperial period. The speech by Apuleius (De magia) defending himself against a charge of bewitching a wealthy heiress in a North African town is particularly important.[Source: Arnaldo Momigliano (1987), Simon Price (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

The relationship of this stereotype to the reality of magical practice is, however, complex. Magic was an important part of the fictional repertoire of Roman writers, but it was not only a figment of the imagination of the elite; and its practice may have become more prominent through the principate — a consequence perhaps of it too (like other forms of knowledge) becoming partially professionalized in the hands of literate experts in the imperial period. So, for example, the surviving Latin curses (often scratched on lead tablets, and so preserved) increase greatly in number under the Empire, and the Greek magical papyri from Egypt are most common in the third and fourth centuries ce. Roman anxieties about magic may, in part, have been triggered by changes in its practices and prominence, as well as by the internal logic of their own worldview.

Divination had been central to republican politics and to the traditional religion of the Roman state. For example, before engagement in battle or before any meeting of an assembly the "auspices" were taken — in other words, the heavens were observed for any signs (such as the particular pattern of a flight of birds) that the gods gave or withheld their assent to the project in hand. These forms of divination changed in Rome under the principate. The traditional systematic reporting of prodigies, for example, disappeared in the Augustan period: these seemingly random intrusions of divine displeasure must have appeared incongruous in a system where divine favor flowed through the emperor; such prodigies as were noted generally centered on the births and deaths of emperors. There were many other forms of divination. Some of them (such as astrology) involved specific foretelling of the future. Some (such as dream interpretation) were a private, rather than a public, affair. Some could even be practiced as a weapon against the current political order — as when casting an emperor's horoscope foretold his imminent death.

The practitioners of divination were as varied as its functions. They ranged from the senior magistrates (who observed the heavens before an assembly) and the state priests (such as the augures who advised the magistrates on heavenly signs) to the potentially dangerous astrologers and soothsayers. These people were periodically expelled from the city of Rome and under the principate were subject to control by provincial governors. The jurist Ulpian included in his treatise on the duties of provincial governors a section explaining the regulation of astrologers and soothsayers; a papyrus document survives from Roman Egypt, with a copy of a general ban on divination issued by a governor of the province in the late second century ce (on the grounds that it led people astray and brought danger); and at the end of the third century ce the emperor Diocletian issued a general ban on astrology. Consultation of diviners that threatened the stability of private families or the life of the emperor himself were obvious targets for punishment.

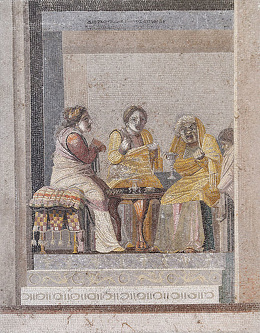

Embrace of Cults in A.D. 1st and 2nd Centuries Rome

hand used in the worship of Sabazios from different angles, AD 1st–2nd century; the hand is decorated with religious symbols that were designed to stand in sanctuaries or were carried on poles in processions

Jerome Carcopino wrote: In the second century of our era cults were in process of submerging the city. The cults of Anatolia had been naturalised in Rome by Claudius' decree . which reformed the liturgy of Cybele and of Attis. The Egyptian cults, banished by Tiberius, were publicly welcomed back by Caligula; and the Temple of Isis in Rome which was destroyed by fire was rebuilt by Domitian with a luxury still testified to by the obelisks that remain standing in the Temple of Minerva or near by in front of the Pantheon, and by the colossal statues of the Nile and of the Tiber. Atargatis, or the Dea Syra, was the only deity to whom Nero, denier of all other gods, deigned to render homage. Finally, it is certain that in Flavian times sanctuaries of Mithra had been established at Rome as at Capua. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” By Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The numerous colleges devoted to these heterogeneous gods at Rome not only co-existed without friction but collaborated in their recruiting campaigns. There was in fact more affinity and mutual understanding between these diverse religions than rivalry. One and all were served by priests jealously segregated from the crowd of the profane; their doctrine was based on revelation, and their prestige on the singularity of their costume and manner of life. One and all imposed preliminary initiation on their followers and periodical recourse to a more or less ascetic regimen; each, after its own fashion, indulged in the same astrological and henotheistic speculations and held out to believers the same messages of hope.

Some of their rites no doubt, like the bull sacrifice of the Great Mother or the procession of the torn-up pine which accompanied the mutilation of Attis, have something both barbarous and indecent in them, "like a whiff from slaughter-house or latriae." Nevertheless, the religions which practiced them exercised a tonic and beneficent influence on individuals and lifted them to a higher plane.

Romans who had not been seduced by these exotic cults suspected and hated them. Juvenal, for instance, who could not repress his wrath to see the Orontes pour her muddy floods of superstition into the Tiber, hit out with might and main against them all, without distinction. While Tiberius seized on the pretext of a case of adultery which had been abetted by some priests of Isis to expel the lot, 10 ? the satirist raged indiscriminately against all oriental priests, charging them with roguery and charlatanism: Chaldean, Commagenian, Phrygian, or priest of Isis, 'Who with his linen-clad and shaven crew runs through the streets under the mask of Anubis and mocks at the weeping of the people." Juvenal never wearies of exposing the shameless exploitation they practice, selling the indulgence of their god to frail female sinners "bribed no doubt by a fat goose and a slice of sacrificial cake," or promising on the strength of their prophetic gifts and powers of divination "a youthful lover or a big bequest from some rich and childless man." He declaims against their obscenity, attacking "the chorus of the frantic Bejlona and the Mother of the Gods, attended by a giant eunuch to whom his obscene inferiors must do reverence"; and "the mysteries of Bona Dea, the Good Goddess, when the flute stirs the loins and the Maenads of Priapus sweep along, frenzied alike by the horn blowing and the wine, whirling their locks and howling. What foul longings burn within their breasts! What cries they utter as the passion beats within!" He holds his sides with laughter at sight of the penances and self-mortifications to which the male and female devotees submit with sombre fanaticism : the woman "who in winter will go down to the river of a morning, break the ice, and plunge three times into the Tiber"; then, "naked and shivering she will creep on bleeding knees right across the field of Tarquin the Proud"; and the other who "at the command of White lo will journey to the confines of Egypt and fetch water from hot Meroe with which to sprinkle the Temple of Isis."

Control of Cults and Foreign Gods by the Roman Emperor

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: Within the city of Rome, however, the emperor was in virtual control of the public cults. As a Greek god, Apollo had been kept outside of the pomerium since his introduction into Rome: his temple was in the Campus Martius. Under Augustus, however, Apollo received a temple inside the pomerium on the Palatine in recognition of the special protection he had offered to Octavian. The Sibylline Books, an ancient collection of prophecies that previously had been preserved on the Capitol, were now transferred to the new temple. Later, Augustus demonstrated his preference for Mars as a family god, and a temple to Mars Ultor (the avenger of Caesar's murder) was built. It was no doubt on the direct initiative of Hadrian that the cult of Rome as a goddess (in association with Venus) was finally introduced into the city centuries after the cult had spread outside of Italy. A temple to the Sun (Sol), a cult popular in the Empire at large and not without some roots in the archaic religion of Rome, had to wait until Emperor Aurelian in 274 ce, if one discounts the cult of the Ba'al of Emesa, a sun god, which came and went with the emperor Elagabalus in 220–221 ce. Another example of these changes inside Rome is that Emperor Claudius found the popularity of these alien cults partially responsible for the neglect of the art of haruspicy among the great Etruscan families, and he took steps to revive the art (Tacitus, Annals 11.15, 47 ce). [Source: Arnaldo Momigliano (1987), Simon Price (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

A further step in the admission of "Oriental gods" to the official religion of Rome was the building of a temple to Isis. In the late Republic, the cult was formally suppressed, only for the triumvirs to vow a shrine to the goddess in 43 B.C., and official action was taken once more against the cult under Augustus and Tiberius. At some point between then and the fourth century ce, festivals of Isis entered the official Roman calendar, possibly under the emperor Gaius Caligula. From at least the second century ce, the main Roman sanctuary of Isis on the Campus Martius was architecturally related to the east side of the Saepta, or official voting area, and to other public monuments in this area, which suggests its integration into the official landscape of Rome. It was, however, the only new foreign sanctuary, so far as can be discovered from the surviving fragments, to be represented on the third-century ce official map of the city of Rome. Jupiter Dolichenus, a god from northern Syria popular among soldiers, was probably given a temple on the Aventine in the second century ce.

There is some evidence that the Roman priestly colleges intervened in the cults of municipia and coloniae (in relation to the cult of Mater Magna), but on the whole it is unreasonable expect the cults of Rome herself to remain exemplary for Roman citizens living elsewhere. For example, Vitruvius, who dedicated his work on architecture to Octavian before the latter became Augustus in 27 B.C., assumes that in an Italian city there should be a temple to Isis and Sarapis (De architectura 1.7.1), but Isis was kept out of Rome in those years. Emperor Caracalla, however, presented his grant of Roman citizenship to the provincials in 212 ce in hope of contributing to religious unification: "So I think I can in this way perform a [magnificent and pious] act, worthy of their majesty, by gathering to their rites [as Romans] all the multitude that joins my people" (Papyrus Giessen 40). Although the cult of Zeus Kapetolios appears three years later at the Greek city of Ptolemais Euergetis in Egypt, the general results of Caracalla's grant were modest in religious terms.

Coins and medals, insofar as they were issued under the control of the central government, provide some indication of imperial preferences in the matter of gods and cults, as well as when and how certain Oriental cults (such as that of Isis, as reflected on coins of Vespasian) or certain attributes of a specific god were considered helpful to the Empire and altogether suitable for ordinary people who used coins. But because as a rule it avoided references to cults of rulers, coinage can be misleading if considered alone. Imperial cult and Oriental cults are, in fact, two of the most important features of Roman religion in the imperial period. But it is crucial to take into consideration popular, not easily definable trends; the religious beliefs or disbeliefs of the intellectuals; the greater participation of women in religious and in intellectual life generally; and, finally, the peculiar problems presented by the persecution of Christianity.

Constantine and Christianity

Constantine

Constantine is generally known as the “first Christian emperor.” The story of his miraculous conversion is told by his biographer, Eusebius. It is said that while marching against his rival Maxentius, he beheld in the heavens the luminous sign of the cross, inscribed with the words, “By this sign conquer.” As a result of this vision, he accepted the Christian religion; he adopted the cross as his battle standard; and from this time he ascribed his victories to God, and not to himself. The truth of this story has been doubted by some historians; but that Constantine looked upon Christianity in an entirely different light from his predecessors, and that he was an avowed friend of the Christian church, cannot be denied. His mother, Helena, was a Christian, and his father, Constantius, had opposed the persecutions of Diocletian and Galerius. He had himself, while he was ruler in only the West, issued an edict of toleration (A.D. 313) to the Christians in his own provinces. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Holland Lee Hendrix told PBS: “Constantine's conversion to Christianity, I think, has to be understood in a particular way. And that is, I don't think we can understand Constantine as converting to Christianity as an exclusive religion. Clearly he covered his bases. I think the way we put it in contemporary terms is "Pascal's Wager" -- it's another insurance policy one takes out. And Constantine was a consummate pragmatist and a consummate politician. And I think he gauged well the upsurge in interest and support Christianity was receiving, and so played up to that very nicely and exported it in his own rule. But it's clear that after he converted to Christianity he was still paying attention to other deities. We know this from his poems and we know it from other dedications as well. [Source: Holland Lee Hendrix, President of the Faculty Union Theological Seminary, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“But what's important to understand and appreciate about Constantine is that Constantine was a remarkable supporter of Christianity. He legitimized it as a protected religion of the empire. He patronized it in lavish ways. ... And that really is the important point. With Constantine, in effect the kingdom has come. The rule of Caesar now has become legitimized and undergirded by the rule of God, and that is a momentous turning point in the history of Christianity. ...

See Separate Article: CONSTANTINE THE GREAT (A.D. 312-37) AND CHRISTIANITY IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

Revival of Paganism in Ancient Rome and Then the Banning of It

The Emperor Julian ("the Apostate") (born A.D. 332, ruled .361-d.363) ruled about three years about 25 years after Constantine’s death. A follower of Mithraism, which he called "the guide of the souls", he tried to undo the work of Constantine and led a concerted effort to re-instate paganism as the dominant religion in the empire. He may not have expected to uproot the new religion entirely; but he hoped to deprive it of the important privileges which it had already acquired. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ]

Constantine I’s actions beginning in A.D. 311 paved the way for the toleration of Christianity but Christianity did not become the legal religion of the Roman Empire until the reign of Theodosius I (A.D. 379-395). He not only made Christianity the official religion of the Empire, he declared other religions illegal. The Codex Theodosianus reads: “XV.xii.1: Bloody spectacles are not suitable for civil ease and domestic quiet. Wherefore since we have proscribed gladiators, those who have been accustomed to be sentenced to such work as punishment for their crimes, you should cause to serve in the mines, so that they may be punished without shedding their blood. Constantine Augustus. [Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. IV: The Early Medieval World, pp. 69-71.

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: Theodosius forbade even private pagan cults (Codex Theodosianus 16.10.12). In the same year, following riots provoked by a special law against pagan cults in Egypt, the Serapeum of Alexandria was destroyed. The significance of this act was felt worldwide. The brief pagan revival of 393, initiated by the usurper Eugenius, a nominal Christian who sympathized with the pagans, was soon followed by other antipagan laws. Pagan priests were deprived of their privileges in 396 (Codex Theodosianus 16.10.4), and pagan temples in the country (not in towns) were ordered to be destroyed in 399 (Codex Theodosianus 16.10.16) — though in the same year, festivals that appear to have been pagan were allowed (Codex Theodosianus 16.10.17). [Source: Arnaldo Momigliano (1987), Simon Price (2005),Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

After the fall of Emperor Eugenius (A.D. 392–394), who restored some pagan temples and was relatively paganism friendly, Theodosius's ban on sacrifices was more effectively applied, and the implications of the old calendar for public life were revised. Traditional public festivals were not banned, but they were officially marginalized in favor of Christian festivals. The last pagan senatorial priests are attested in the 390s, the series of dedicatory inscriptions from the sanctuary of Mater Magna in the Vatican area runs from A.D. 295 to 390, and the last dated Mithraic inscription from Rome is from A.D. 391 (slightly later than from elsewhere in the Empire). Some Christians went on the offensive, destroying pagan sanctuaries, including sanctuaries of Mithras. The sanctuary of the Arval Brothers was dismantled from the late fourth century onward.

CHRISTIANITY IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE AFTER CONSTANTINE europe.factsanddetails.com

Paganism Hangs On in the Christianization Roman Empire

According to Encyclopedia.com: Despite the decay of the old oman religion in Rome and other large urban centers in the West and the triumph of the mystery religions, and subsequently that of Christianity in these same centers, the old Roman agrarian cults and magic practices retained their vitality in the more remote municipalities and, above all, in country districts. The popular sermons of St. Augustine, Maximus of Turin, and other Christian preachers of the late 4th and early 5th centuries refer repeatedly to the continued observance of old pagan feasts and the resort to magic practices. Even as late as the 6th century martin of braga and caesarius of arles found it necessary to condemn by name pagan superstitions and practices mentioned in the calendars of the late Republic and early Empire. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

According to Encyclopedia.com: Despite the decay of the old Roman religion in Rome and other large urban centers in the West and the triumph of the mystery religions, and subsequently that of Christianity in these same centers, the old Roman agrarian cults and magic practices retained their vitality in the more remote municipalities and, above all, in country districts. The popular sermons of St. Augustine, Maximus of Turin, and other Christian preachers of the late 4th and early 5th centuries refer repeatedly to the continued observance of old pagan feasts and the resort to magic practices. Even as late as the 6th century martin of braga and caesarius of arles found it necessary to condemn by name pagan superstitions and practices mentioned in the calendars of the late Republic and early Empire. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

Rome in the A.D. fourth century remained for some people a city characterized by the worship of the ancient gods. The pagan historian Ammianus Marcellinus, when describing the visit of the emperor Constantius II to Rome in A.D. 357, depicted the (Christian) emperor admiring the temples and other ancient ornaments of the city (16.10.13–17). This account tendentiously suppresses any mention of Christianity or Judaism in Rome. The traditional monuments of the city were duly restored in the course of the A.D. fourth century by the prefectus urbi (prefect of the city). The traditional religious practices of Rome were not mere fossilized survivals. They did not incorporate elements of Christianity or Judaism, but there were continuing changes and restructuring through the fourth century. For example, in the Calendar of A.D. 354, games in honor of the emperor continued to be remodeled and adjusted to the new rulers, and the cycle of festivals in honor of the gods was also reworked. [Source: Arnaldo Momigliano (1987), Simon Price (2005),Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

The process of change is also visible in cults long established in Rome, which sometimes received new and heady interpretations. In the fourth century the cult of Mater Magna placed a new emphasis on the practice of the taurobolium (bull sacrifice). Inscriptions from the sanctuary in the Vatican area record that some worshippers repeated the ritual after a lapse of twenty years. The process of incorporation of once foreign cults into the "official" religion is most visible in the priesthoods held by members of the senatorial class. Until the end of the fourth century, senators continued to be members of the four main priestly colleges, but there were, in addition, priests of Hecate, Mithras, and Isis.

But traditional religious rites were very tenacious, and their demise cannot be assumed from the ending of dedicatory inscriptions. Emperors through the fifth and into the sixth century elaborated Theodosius's ban on sacrifices — presumably in the face of the continuing practice of traditional sacrifice, for a pagan writer traveling up from Rome through Italy in the early fifth century observed with pleasure a rural festival of Osiris. Even at the end of the A.D. fifth century, the Lupercalia was still being celebrated in Rome. The bishop of Rome found it necessary both to argue against the efficacy of the cult and to ban Christian participation. Hopes that the pagan gods would come back excited the Eastern provinces during the rebellion against the emperor Zeno in about 483.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024