RELIGION IN ANCIENT GREECE

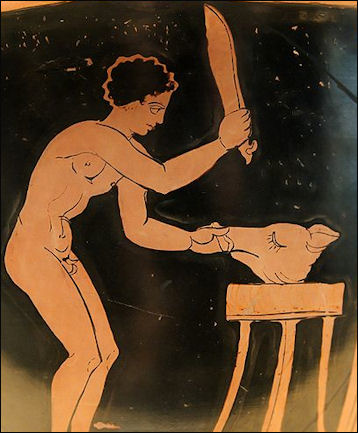

Sacrifice of a pig The Greeks had no word for religion. There was no distinction between the sacred and secular: What we now call religion was intertwined with daily life and the state. The Greeks were described by Christians as pagans (believers in multiple gods). The word “paganism” comes from the Greek word meaning “all.” The Greek belief in gods extended well beyond the ones we know.

It appears religion was important in the everyday life of individuals in ancient Greece. Greek religion did not appoint any fixed ceremonies to be observed every day; but still it placed a believer in connection with the Deity, and thus gave occasion for some religious act every day. There were also some special occasions which led ancient Greeks to turn to their gods. It was rare that they required the mediatory help of a priest; as a rule, any Greek might perform the various religious ceremonies himself or herself. In the oldest literary monument of Greek life, the Homeric poems, worship was chiefly in the hands of laymen, and service in the temples and priesthood generally played a very subordinate part in religious life. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Greek religion was more a series of rituals than a code or moral behavior as ritual and sacrifice were at its heart. There was a strong belief in fate. The Greeks tended to believe that there no accidents: that the gods were behind everything. Like the Egyptians, the Greeks believed that consciousness resided in the heart, a view that would prevailed through the Middle Ages.

Greek religion often placed the ideals of beauty and heroics on a higher level than those for morality. The Gods were more often than not are seen as being that could enjoy and indulge themselves in things beyond the means of mortals rather than beings that guided humans and rewarded and punished them on the basis of their righteousness or sins.

Books: “ Mythology, Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes” by Edith Hamilton (1940, New American Library), “Book of Greek Myths” by Ingri and Edgar Parin d'Aulaire (1962, Doubleday & Company); “Thomas Bulfinch Myths of Greece and Rome” compiled by Joseph Campbell (1979, Viking Penguin); “The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth & Religion” ; “ Mythology, Myths, Legends & Fantasies” by Global Publishing.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Greek Religion; Archaic and Classical Periods” by Walter Burkert (1985) Amazon.com;

“Miasma: Pollution and Purification in Early Greek Religion” by Robert Parker (1983) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Greek Religion” by Esther Eidinow, Julia Kindt (2015) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greek Religion” by Daniel Ogden (2007) Amazon.com;

“On Greek Religion” by Robert Parker (Cornell Studies) (2011) Amazon.com;

“A History of Greek Religion” by Martin P. Nilsson (1925) Amazon.com;

“Dawn of the Gods” by Jacquetta Hawkes (1968) Amazom.com

“The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion” by Martin. Nilsson (1968) Amazon.com;

“Religions of the Hellenistic-Roman Age” by Antonia Tripolitis (2001) Amazon.com;

“Homo Necans: The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth”

by Walter Burkert and Peter Bing (1972) Amazon.com;

“Savage Energies: Lessons of Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece” by Walter Burkert (2001) Amazon.com;

“Girls and Women in Classical Greek Religion” by Matthew Dillon (2002) Amazon.com;

Case for Polytheism

The Greeks practiced polytheism: the worship of many gods. Polytheists have traditionally been looked down upon by practitioners of the great monotheistic religion which worship only a single god — Judaism, Christianity, Islam — as primitive and barbaric pagans. But who knows maybe they had it right.

Mary Leftowitz, a classics professor at Wellesley College, argues that a lot of world’s troubles today can be blamed in monotheism. In the Los Angeles Times she wrote, “The polytheistic Greeks didn’t advocate killing those who worshiped a different gods, and they did not pretend that their religion provided all the right answers. Their religion made the ancient Greeks aware of their ignorance and weakness, letting them recognize multiple points of view. ..It suggests that collective decisions often lead to better outcomes. Respect for a diversity of viewpoints informs the cooperative system the Athenians called democracy.”

“Unlike the monotheistic traditions Greco-Roman polytheism was multicultural...The world, as the Greek philosopher Thales wrote, is full of gods, and all deserve respect and honor. Such a generous understanding of nature called the ancient Greeks and Romans to accept and respect other people’s gods and to admire (rather than despise) other nations for their own notions of piety. If the Greeks were in close contact with a particular nation they gave their foreign gods names of their own gods: The Egyptian goddess Isis was Demeter; Horus was Apollo and so on.”

Ancient Greek Religious Beliefs

altar for Aphrodite and Adonis Mary Leftowitz, a classics professor at Wellesley College wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “As the Greeks saw it the gods made life hard for humans, didn’t seek to improve the human condition and allowed people to suffer and die. As a palliative, the gods could offer only to see that great achievement were immortalized. There was no hope of redemption, no promise of a happy life or rewards after death. If things did go wrong, as they inevitably did, humans had to seek comfort not from gods but from other humans.”

“The separation between humankind and the gods made it possible for humans to complain to the gods without the guilt and fear of reprisal the deity of the Old Testament inspired. Mortals were free to speculate about the character and intentions of the gods. By allowing mortals to ask hard questions, Greek theology encouraged them to learn, to seek all the possible causes of events, Philosophy — that characteristic Greek invention — had its roots in such theological inquiry, as did science.”

“Paradoxically, the main advantage of ancient Greek religion lies in this ability to recognize and accept human fallibility. Mortals cannot suppose that they have all the answers, the people most likely to know what to do are prophets directly inspired by god, yet prophets inevitably meet resistance, because people hear only what the wish to hear, whether or not it is true. Mortals are particularly prone to error at the moments when they think they know what they are doing. The gods are fully aware of this human weakness. If they decide to communicate with the mortals, they tend to do so only indirectly by signs and portents which mortals often misinterpret....Greek religion openly discourages blind confidence based on unrealistic hopes that everything will work out.”

Ancient Greek Myths

Persephone in the Underworld Mythology and religion were intertwined in ancient Greek and Roman religion. Many elements and figures in Greek religion and mythology have become important elements and icons in modern European and American culture. The word myth comes from “ mythos” , the Greek word which meant both “truth” and “word.”

Myths were popular in ancient times because they helped explain the complexities of the universe in ways that human beings could understand and also explained things in the past that no one observed directly. Myths appeared in many culture to explain things like why the sun disappeared at night and reappeared in the day; to sort out why natural disasters occur; explain what happens to people when they die; to create a credible story as how the universe and mankind were created. Because so many of things were unexplainable it was simple enough to create gods and say did the did the unexplainable things.

The myths on similar subjects — such as the coming of spring and the presence of gods in the sky — are often remarkably similar in cultures that have and never have had contact with one another. Flood stories after creation, for example are very common. By the same token, the telling of a certain myth can vary in small ways and in large between groups of a certain time period or area within a culture.

The originators of the Greek myths are unknown. The sources of many of the myths are Homer’s epics, the plays by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides and other writings that have been passed down over the centuries. In some cases the stories were not spelled out but have been inferred from references to them in other stories. The story of creation and other stories comes from “ Theogony” by the Greek poet Hesiod (750-675B.C.), who claims the Muses told him the story while he was tending sheep.

See Separate Articles Under GODS AND MYTHOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

Minoan Religion

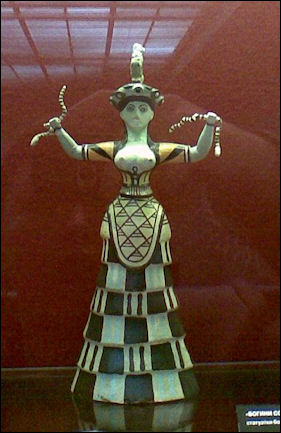

Minoan snake goddess The Minoans preceded the Greeks and Mycenaeans. They thrived from about 2100 to 1600. B.C. While we can only guess at their religious beliefs, the remains of their artwork suggest a polytheistic framework featuring various goddesses, including a mother deity. The priesthood was also completely female, although the King may have had some religious functions as well. In fact the role of women- as religious leaders, entrepreneurs, traders, craftspeople and athletes far exceeded that of most other societies, including the Greeks. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

The Minoans had no temples and no large cult statues from what we can tell. Worship centered around sacred caves and groves where it is believed the Minoans believed to be their deities dwelled. Minoan religious objects consisted primarily of small terra-cotta statuettes.

The Minoans worshiped what has been described as a mother goddess, or snake goddess. This goddess was associated with animals, particularly birds and snakes, the pillar and the tree, and sword and the double ax. She was often depicted with snakes around her arms and lions at her feet. Her companion Zeus, the Monoans believed, was born on Mt. Ida on Crete. A popular image of the mother goddess shows her as a bare breasted snake goddess with snakes crawling up her arms, circling her head and tied into a knot about her waist. One of the unusual things about the worship of snakes by the Minoans is that Crete has virtually no snakes.

Most of the sculpture of earth goddesses found before in 2000 B.C. in mainland Europe were plump big-breasted women with folds of fat and little lines representing their genitalia. On Asia Minor and the Cycladic islands off of Greece little girlish figures with small beasts triangles for genitalia were common between 2500-1100 B.C.

The Minoans also worshiped male deities as reflected in the large number of male figures found and the quality of their craftsmanship. Egyptian symbols and deities, such as Orisis and Anubis, pop up frequently in Minoan religious iconography. Butterflies symbolized long life to the Minoans and bulls represented strength and fertility.

Human sacrifice although rare were sometimes performed. Skeletons and artifact from the archeological site of Anemospilia seem to show a human sacrifice that was interrupted in mid-course by an earthquake which not only finished off the sacrifice victim but also spelled doom for the sacrificers as well.

See Separate Article: MINOAN LIFE: SOCIETY, RELIGION, FOOD, BATHTUBS europe.factsanddetails.com

Mycenaean Religion

The Mycenaeans (1600-1100 B.C) came after the Minoans preceded the Greeks. Linear B, their written language, mentions Zeus, Athena, Hera, Hermes, and Poseidon and tributes of oxen, sheep, goats pigs, wine, perfumed oil and wheat given to the gods. Deities resembling the Madonna and father-holy-ghost- child trilogy of Christianity were present in Mycenae. Some archaeologists believe the Mycenaeans performed animal sacrifices based on charred bones found at an alter. A tablet discovered with a sort of SOS on it seems to indicate that sacrifices were held after some catastrophe. The tablet was sort of a call for help.

The Mycenaeans started burying their dead in deep shaft graves around 1600 B.C. and later built huge beehive tombs and chamber tombs cut into hillsides. The deceased were buried with gold and silver masks of themselves and jewelry, toys, combs, baby bottles, tools, weapons and vessels. Often times several family members were buried in the same tomb.

Mycenaean stirrup vase Mycenaean Divinities (God, Alternative Name, Mycenaean Greek Place Found

Zeus (Jupiter), Di-u-ja (Month-name Diwioios), Knossos

Hera (Juno), E-ra, Pylos

Poseidon (Neptune), Po-se-do-o and Also the Cult-title E-ne-si-da-o-ne ('Earth-shaker'), Knossos

Ares (Mars), Knossos

Apollo, Pa-ja-wo [= Paian ], Knossos

Hermes (Mercury), Hermes Araios (Ram) Py,, Knossos

Athena (Minerva), A-ta-na Po-ti-ni-ja (Potnia), Knossos

Dionysos (Bacchus), Di-wo-ni-so-jo, Pylos

Eileithyeia, E-re-u-ti-ja, Knossos

Erinyes (Furies), Knossos

Anemoi (the Winds), A-ne-moi, Pylos

Iphimedeia (Iphigeneia, Homeric Person), Knossos

Daedalus, (a place called "Daidaleion"), Knossos

and many other lesser local divine names, esp. Potnia

[Source: John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class]

Their religious beliefs seem to have been very similar to those of other ancient civilizations of the time and share in two important characteristics- polytheism and syncretism. Polytheism is a belief in many gods and syncretism reflects a willingness to add foreign gods into the belief system-even if the new additions don't exactly fit. When the Mycenaeans first arrived in the Aegean they likely believed in a pantheon of gods headed by a supreme Sky God common to most Indo-European peoples. His name was Dyeus which in Greek became Zeus. Following contact with the Minoans and their earth goddesses, these goddesses were incorporated into the pantheon and that is likely the path followed by Hera, Artemis and Aphrodite.” [Source: Canadian Museum of History ]

See Separate Article: MYCENAEAN RELIGION: BEEHIVE TOMBS AND MAYBE HUMAN SACRIFICES europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Greek Religion

The roots of religion in Greece date back to early sites where civic cults met, local gods were worshiped and festivals and ceremonies were held. Sacred places also commemorated the legendary dwellings of the gods, such as Olympus. The ancient Greeks believed that their gods and goddesses would protect them and guide them if they were treated properly. A key element of this was worshipping the the gods by carrying out ceremonies and sacrifices. The Greeks worshiped their gods affect their fate while living and secure a relatively good place in the afterlife. By the fourth century B.C., cults had emerged that claimed to offer purification by cleansing initiates of the stain of humanity.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Ancient Greek religious practice, essentially conservative in nature, was based on time-honored observances, many rooted in the Bronze Age (3000–1050 B.C.), or even earlier. Although the Iliad and the Odyssey of Homer, believed to have been composed around the eighth century B.C., were powerful influences on Greek thought, the ancient Greeks had no single guiding work of scripture like the Jewish Torah, the Christian Bible, or the Muslim Qu'ran. Nor did they have a strict priestly caste. The relationship between human beings and deities was based on the concept of exchange: gods and goddesses were expected to give gifts. Votive offerings, which have been excavated from sanctuaries by the thousands, were a physical expression of thanks on the part of individual worshippers. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

Olympia's Zeus Temple

To the people of ancient Greece (as well as to earlier and neighboring civilizations) the universe they knew was filled with terrible forces not fully understood. Occasionally they saw dramatic demonstrations of power and might - violent thunderstorms, raging seas, gale force winds, eclipses, plagues, drought, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, etc. It was not unreasonable to suspect that powerful and unpredictable entities were the cause of these events and that the originators might be appeased through prayer and sacrifice. In ancient times and in truly grave circumstances the ultimate gift of human sacrifice was made to placate those supernatural beings. [Source: Canadian Museum of History ]

“The ancient Greeks had no word for “religion” which they viewed as being part of everything they did. Nor did they believe in the separation of “church” and state. It was felt that the safety and security of the state was dependent on a good relationship with the gods. Anyone who offended the gods could be found guilty of impiety and sentenced to death, as happened to Socrates. No one undertook anything of an important nature- such as a voyage, a battle or a construction project without first seeking the blessings or support of a particular god. And when the task was successfully completed, thanks were given in the form of offerings or, perhaps, by the dedication of a plaque or monument. It was this practice that gave birth to most public buildings and monuments including the altar of Zeus at Pergamun and the renowned Parthenon. |

“If you find Greek religion and mythology to be a bit confusing and contradictory and feel that the behavior of some of the gods and goddesses was sometimes outrageous and improbable, then you are not alone. You are in the company of many Greeks who began some one hundred generations ago to question as to whether or not there might be better (although less interesting) explanations about the origins of the universe and themselves. They took their first steps into the discipline of philosophy.

Religious Athenians

Athena, Athen's patron goddess

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “In the Athenian market-place among the objects not generally known is an altar to Mercy, of all divinities the most useful in the life of mortals and in the vicissitudes of fortune, but honored by the Athenians alone among the Greeks. And they are conspicuous not only for their humanity but also for their devotion to religion. They have an altar to Shamefastness, one to Rumour and one to Effort. It is quite obvious that those who excel in piety are correspondingly rewarded by good fortune. In the gymnasium not far from the market-place, called Ptolemy's from the founder, are stone Hermae well worth seeing and a likeness in bronze of Ptolemy. Here also is Juba the Libyan and Chrysippus1 of Soli.Hard by the gymnasium is a sanctuary of Theseus, where are pictures of Athenians fighting Amazons. This war they have also represented on the shield of their Athena and upon the pedestal of the Olympian Zeus. In the sanctuary of Theseus is also a painting of the battle between the Centaurs and the Lapithae. Theseus has already killed a Centaur, but elsewhere the fighting is still undecided. The painting on the third wall is not intelligible to those unfamiliar with the traditions, partly through age and partly because Micon has not represented in the picture the whole of the legend. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“I have already stated that the Athenians are far more devoted to religion than other men. They were the first to surname Athena Ergane (Worker); they were the first to set up limbless Hermae, and the temple of their goddess is shared by the Spirit of Good men. Those who prefer artistic workmanship to mere antiquity may look at the following: a man wearing a helmet, by Cleoetas, whose nails the artist has made of silver, and an image of Earth beseeching Zeus to rain upon her; perhaps the Athenians them selves needed showers, or may be all the Greeks had been plagued with a drought. There also are set up Timotheus the son of Conon and Conon himself; Procne too, who has already made up her mind about the boy, and Itys as well--a group dedicated by Alcamenes. Athena is represented displaying the olive plant, and Poseidon the wave, and there are statues of Zeus, one made by Leochares and one called Polieus (Urban), the customary mode of sacrificing to whom I will give without adding the traditional reason thereof. Upon the altar of Zeus Polieus they place barley mixed with wheat and leave it unguarded. The ox, which they keep already prepared for sacrifice, goes to the altar and partakes of the grain. One of the priests they call the ox-slayer, who kills the ox and then, casting aside the axe here according to the ritual runs away. The others bring the axe to trial, as though they know not the man who did the deed. Their ritual, then, is such as I have described.

Homer, Hesiod and Early Greek Thought and Cosmology

John Burnet wrote in “Early Greek Philosophy”: “We see the working of these influences clearly in Homer. Though he doubtless belonged to the older race himself and used its language, it is for the courts of Achaean princes he sings, and the gods and heroes he celebrates are mostly Achaean. That is why we find so few traces of the traditional view of the world in the epic. The gods have become frankly human, and everything primitive is kept out of sight. There are, of course, vestiges of the early beliefs and practices, but they are exceptional. It has often been noted that Homer never speaks of the primitive custom of purification for homicide. The dead heroes are burned, not buried, as the kings of the older race were. Ghosts play hardly any part. In the Iliad we have, to be sure, the ghost of Patroclus, in close connection with the solitary instance of human sacrifice in Homer. There is also the Nekyia in the Eleventh Book of the Odyssey. Such things, however, are rare, and we may fairly infer that, at least in a certain society, that of the Achaean princes for whom Homer sang, the traditional view of the world was already discredited at a comparatively early date, though it naturally emerges here and there. [Source: John Burnet (1863-1928), “Early Greek Philosophy” London and Edinburgh: A. and C. Black, 1892, 3rd edition, 1920, Evansville University ]

“When we come to Hesiod, we seem to be in another world. We hear stories of the gods which are not only irrational but repulsive, and these are told quite seriously. Hesiod makes the Muses say: "We know how to tell many false things that are like the truth; but we know too, when we will, to utter what is true." This means that he was conscious of the difference between the Homeric spirit and his own. The old lightheartedness is gone, and it is important to tell the truth about the gods. Hesiod knows, too, that he belongs to a later and a sadder time than Homer. In describing the Ages of the World, he inserts a fifth age between those of Bronze and Iron. That is the Age of the Heroes, the age Homer sang of. It was better than the Bronze Age which came before it, and far better than that which followed it, the Age of Iron, in which Hesiod lives. He also feels that he is singing for another class. It is to shepherds and husbandman of the older race he addresses himself, and the Achaean princes for whom Homer sang have become remote persons who give "crooked dooms." The romance and splendor of the Achaean Middle Ages meant nothing to the common people. The primitive view of the world had never really died out among them; so it was natural for their first spokesman to assume it in his poems. That is why we find in Hesiod these old savage tales, which Homer disdained.

Main figures in the Hesiod's Theogony creation story

“Yet it would be wrong to see in the Theogony a mere revival of the old superstition. Hesiod could not help being affected by the new spirit, and he became a pioneer in spite of himself. The rudiments of what grew into Ionic science and history are to be found in his poems, and he really did more than anyone to hasten that decay of the old ideas which he was seeking to arrest. The Theogony is an attempt to reduce all the stories about the gods into a single system, and system is fatal to so wayward a thing as mythology. Moreover, though the spirit in which Hesiod treats his theme is that of the older race, the gods of whom he sings are for the most part those of the Achaeans. This introduces an element of contradiction into the system from first to last. Herodotus tells us that it was Homer and Hesiod who made a theogony for the Hellenes, who gave the gods their names, and distributed among them their offices and arts, and it is perfectly true. The Olympian pantheon took the place of the older gods in men's minds, and this was quite as much the doing of Hesiod as of Homer. The ordinary man would hardly recognize his gods in the humanized figures, detached from all local associations, which poetry had substituted for the older objects of worship. Such gods were incapable of satisfying the needs of the people, and that is the secret of the religious revival we shall have to consider later.

Evolution of Cosmogony in Ancient Greece

John Burnet wrote in “Early Greek Philosophy”: “Nor is it only in this way that Hesiod shows himself a child of his time. His Theogony is at the same time a Cosmogony, though it would seem that here he was following the older tradition rather than working out a thought of his own. At any rate, he only mentions the two great cosmogonical figures, Chaos and Eros, and does not really bring them into connection with his system. They seem to belong, in fact, to an older stratum of speculation. The conception of Chaos represents a distinct effort to picture the beginning of things. It is not a formless mixture, but rather, as its etymology indicates, the yawning gulf or gap where nothing is as yet. We may be sure that this is not primitive. Primitive man does not feel called on to form an idea of the very beginning of all things; he takes for granted that there was something to begin with. The other figure, that of Eros, was doubtless intended to explain the impulse to production which gave rise to the whole process. These are clearly speculative ideas, but in Hesiod they are blurred and confused. [Source: John Burnet (1863-1928), “Early Greek Philosophy” London and Edinburgh: A. and C. Black, 1892, 3rd edition, 1920, Evansville University]

“We have records of great activity in the production of cosmogonies during the whole of the sixth century B.C., and we know something of the systems of Epimenides, Pherecydes, and Acusilaus. If there were speculations of this kind even before Hesiod, we need have no hesitation in believing that the earliest Orphic cosmogony goes back to that century too. The feature common to all these systems is the attempt to get behind the Gap, and to put Kronos or Zeus in the first place. That is what Aristotle has in view when he distinguishes the "theologians" from those who were half theologians and half philosophers, and who put what was best in the beginning. It is obvious, however, that this process is the very reverse of scientific, and might be carried on indefinitely; so we have nothing to do with the cosmogonists in our present inquiry, except so far as they can be shown to have influenced the course of more sober investigations.

“The Ionians, as we can see from their literature, were deeply impressed by the transitoriness of things. There is, in fact, a fundamental pessimism in their outlook on life, such as is natural to an over-civilized age with no very definite religious convictions. We find Mimnermus of Colophon preoccupied with the sadness of the coming of old age, while at a later date the lament of Simonides, that the generations of men fall like the leaves of the forest, touches a chord that Homer had already struck. Now this sentiment always finds its best illustrations in the changes of the seasons, and the cycle of growth and decay is a far more striking phenomenon in Aegean lands than in the North, and takes still more clearly the form of a war of opposites, hot and cold, wet and dry. It is, accordingly, from that point of view the early cosmologists regard the world. The opposition of day and night, summer and winter, with their suggestive parallelism in sleep and waking, birth and death, are the outstanding features of the world as they saw it.

four elements and their equivalent body fluid

“The changes of the seasons are plainly brought about by the encroachments of one pair of opposites, the cold and the wet, on the other pair, the hot and the dry, which in their turn encroach on the other pair. This process was naturally described in terms borrowed from human society; for in early days the regularity and constancy of human life was far more clearly realized than the uniformity of nature. Man lived in a charmed circle of social law and custom, but the world around him at first seemed lawless. That is why the encroachment of one opposite on another was spoken of as injustice (adikia) and the due observance of a balance between them as justice (dikê). The later word kosmos is based on this notion too. It meant originally the discipline of an army, and next the ordered constitution of a state.

“That, however, was not enough. The earliest cosmologists could find no satisfaction in the view of the world as a perpetual contest between opposites. They felt that these must somehow have a common ground, from which they had issued and to which they must return once more. They were in search of something more primary than the opposites, something which persisted through all change, and ceased to exist in one form only to reappear in another. That this was really the spirit in which they entered on their quest is shown by the fact that they spoke of this something as "ageless" and "deathless." If, as is sometimes held, their real interest had been in the process of growth and becoming, they would hardly have applied epithets so charged with poetical emotion and association to what is alone permanent in a world of change and decay. That is the true meaning of Ionian "Monism."

Scientific Character of Early Greek Cosmology

John Burnet wrote in “Early Greek Philosophy”: “It is necessary to insist on the scientific character of the philosophy...We have seen that the Eastern peoples were considerably richer than the Greeks in accumulated facts, though these facts had not been observed for any scientific purpose, and never suggested a revision of the primitive view of the world. The Greeks, however, saw in them something that could be turned to account, and they were never as a people slow to act on the maxim, Chacun prend son bien partout où il le trouve. The visit of Solon to Croesus which Herodotus describes, however unhistorical it may be, gives us a good idea of this spirit. Croesus tells Solon that he has heard much of "his wisdom and his wanderings," and how from love of knowledge (philosopheôn), he has traveled over much land for the purpose of seeing what was to be seen (theôriês heineken). The words theôriê, philosophiê and historiê are, in fact, the catchwords of the time, though they had, no doubt, a somewhat different meaning from that they were afterwards made to bear at Athens. [Source: John Burnet (1863-1928), “Early Greek Philosophy” London and Edinburgh: A. and C. Black, 1892, 3rd edition, 1920, Evansville University]

round earth and heavenly spheres

“The idea that underlies them all may, perhaps, be rendered in English by the word Curiosity; and it was just this great gift of curiosity, and the desire to see all the wonderful things -- pyramids, inundations, and so forth -- that were to be seen, which enabled the Ionians to pick up and turn to their own use such scraps of knowledge as they could come by among the barbarians. No sooner did an Ionian philosopher learn half-a-dozen geometrical propositions, and hear that the phenomena of the heavens recur in cycles, than he set to work to look for law everywhere in nature, and, with an audacity almost amounting to hubris, to construct a system of the universe. We may smile at the medley of childish fancy and scientific insight which these efforts display, and sometimes we feel disposed to sympathise with the sages of the day who warned their more daring contemporaries "to think the thoughts befitting man's estate" (anthrôpina phronein). But we shall do well to remember that even now it is just such hardy anticipations of experience that make scientific progress possible, and that nearly every one of these early inquirers made some permanent addition to positive knowledge, besides opening up new views of the world in every direction.

“There is no justification either for the idea that Greek science was built up by more or less lucky guesswork, instead of by observation and experiment. The nature of our tradition, which mostly consists of Placita -- that is, of what we call "results" -- tends, no doubt, to create this impression. We are seldom told why any early philosopher held the views he did, and the appearance of a string of "opinions" suggests dogmatism. There are, however, certain exceptions to the general character of the tradition; and we may reasonably suppose that, if the later Greeks had been interested in the matter, there would have been many more. We shall see that Anaximander made some remarkable discoveries in marine biology, which the researches of the nineteenth century have confirmed (§ 22), and even Xenophanes supported one of his theories by referring to the fossils and petrifactions of such widely separated places as Malta, Paros, and Syracuse (§ 59). This is enough to show that the theory, so commonly held by the earlier philosophers, that the earth had been originally in a moist state, was not purely mythological in origin, but based on biological and palaeontological observations. It would surely be absurd to imagine that the men who could make these observations had not the curiosity or the ability to make many others of which the memory is lost. Indeed, the idea that the Greeks were not observers is ludicrously wrong, as is proved by the anatomical accuracy of their sculpture, which bears witness to trained habits of observation, while the Hippocratean corpus contains models of scientific observation at its best. We know, then, that the Greeks could observe well, and we know that they were curious about the world. Is it conceivable that they did not use their powers of observation to gratify that curiosity? It is true that they had not our instruments of precision; but a great deal can be discovered by the help of very simple apparatus. It is not to be supposed that Anaximander erected his gnomon merely that the Spartans might know the seasons.

Ptolemic model of the cosmos

“Nor is it true that the Greeks made no use of experiment. The rise of the experimental method dates from the time when the medical schools began to influence the development of philosophy, and accordingly we find that the first recorded experiment of a modern type is that of Empedocles with the klepsydra. We have his own account of this (fr. 100), and we can see how it brought him to the verge of anticipating Harvey and Torricelli. It is inconceivable that an inquisitive people should have applied the experimental method in a single case without extending it to other problems.

“Of course the great difficulty for us is the geocentric hypothesis from which science inevitably started, though only to outgrow it in a surprisingly short time. So long as the earth is supposed to be in the center of the world, meteorology, in the later sense of the word, is necessarily identified with astronomy. It is difficult for us to feel at home in this point of view, and indeed we have no suitable word to express what the Greeks at first called an ouranos. It will be convenient to use the term "world" for it; but then we must remember that it does not refer solely, or even chiefly, to the earth, though it includes that along with the heavenly bodies.

“The science of the sixth century was mainly concerned, therefore, with those parts of the world that are "aloft" (ta meteôra), and these include such things as clouds, rainbows, and lightning, as well as the heavenly bodies. That is how the latter came sometimes to be explained as ignited clouds, an idea which seems astonishing to us. But even that is better than to regard the sun, moon, and stars as having a different nature from the earth, and science inevitably and rightly began with the most obvious hypothesis, and it was only the thorough working out of this that could show its inadequacy. It is just because the Greeks were the first people to take the geocentric hypothesis seriously that they were able to go beyond it. Of course the pioneers of Greek thought had no clear idea of the nature of scientific hypothesis, and supposed themselves to be dealing with ultimate reality, but a sure instinct guided them to the right method, and we can see how it was the effort to "save appearances" that really operated from the first. It is to those men we owe the conception of an exact science which should ultimately take in the whole world as its object. They fancied they could work out this science at once. We sometimes make the same mistake nowadays, and forget that all scientific progress consists in the advance from a less to a more adequate hypothesis. The Greeks were the first to follow this method, and that is their title to be regarded as the originators of science.

Mystery Cults in Ancient Greece

There were hundreds of local gods and hundreds of cults, many devoted to specific gods. Many of the cults, were very secretive and had special initiation rituals with sacred tales, symbols, formulas and special rituals oriented towards specific gods. These are often described as mystery cults. Fertility cults and goddesses were often associated with the moon because its phases coincided the menstruation cycles of women and it was thought the moon had power over women.

Dionysiac procession In a review of “Mystery Cults in Ancient World” by Hugh Bowden, Mary Beard wrote in the Times of London, “For modern scholars, it has always been a frustrating task to discover the secret of these ancient mystery cults (“mystery” from the Greek mysterion, which has a range of meaning, from “Eleusinian ritual” to “secret knowledge” in a wider sense). What was it that the initiates of Dionysus or the “Great Mother” knew that the uninitiated did not? In his refreshing new survey, Mystery Cults in Ancient World, Hugh Bowden suggests that we have perhaps been worrying unnecessarily about that question. In fact, we don’t have to imagine the ancients were so much better keepers of secrets than we are, for no secret knowledge, as such, was transmitted at all. To be sure, there was a whole range of objects involved in these cults that outsiders could not see, and words that they were not allowed to hear. (In the cult at Eleusis, from descriptions of the public procession to the sanctuary, we can judge that the cult objects were small — at least small enough comfortably to be carried in containers by the priestesses.) But that is quite different from thinking that some particular piece of secret doctrine was revealed to the faithful at their initiation.

"Bowden’s Mystery Cults is a consistently sensible book in a field where common sense is often lacking (the temptation to see some ancient initiatory rituals as if they were New Age religions has proved almost irresistible). And, in the course of the book he debunks an impressive number of myths about ancient mystery religions. He pours some much-needed cold water over the idea that the inscribed golden “leaves? (offering instructions for navigating the underworld) found with a number of burials in the Greek world attest to a defined “Orphic cult” with advanced ideas of eschatology; better, perhaps, to see them as examples of a much more humdrum commercial religious trade, selling reassurances of a happy afterlife for grieving relatives to put in the graves of their loved ones.

"The book, however, is concerned to do much more than debunk. Taken overall, Bowden’s examples of mystery cults — from the famous rituals of Eleusis to those little communities of Mithraists huddled in their ritual “caves” along Hadrian’s Wall — suggest a much fuzzier boundary with the official, civic cult of Greece and Rome than even he acknowledges. For a start, many of these religions are not only personal and initiatory but also part of the state religious framework. The rituals in the sanctuary at Eleusis, where the secret initiation (whatever it was) happened, were preceded and followed by large public processions of the citizens of Athens. The sanctuary of the Great Mother at Ostia was a place of considerable local splendour, castration or no castration — and, as we know from the inscriptions found there, it was subsidized by grandees of the local community.

Book: "Mystery Cults in the Ancient World” by Hugh Bowden (Thames and Hudson, 2010)

See Separate Article: MYSTERY CULTS IN THE GREEK AND ROMAN WORLD europe.factsanddetails.com ; DIONYSUS CULT europe.factsanddetails.com ; DEMETER MYSTERY CULTS AND MYTHS, STORIES AND HYMNS ABOUT DEMETER europe.factsanddetails.com ; ELEUSINIAN MYSTERY CULTS europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum. The human sacrifice images are from The Guardian

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024