Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society / Culture and Sports / Literature and Drama

ANCIENT GREEK LANGUAGE

Greek dialects The ancient Greek spoken language is thought to have been similar to modern Greek, but like other ancient languages, although we can read it, we don’t known exactly what it sounded like. Based on written texts that have been handed down to us today ancient Greek was a colorful language that could express a wide range of emotions and thoughts.

Even though many words in the modern English are derived from Greek, the Greeks didn’t have a word for “word” until Hellenistic times. Some original Greeks words like “mathematics,” “physics” and “music” have come down to us virtually unchanged. Charisma is a Greek word that literally means “the gift of grace.” It was used in the early Christian era to describe the extraordinary powers given someone by the Holy Ghost. Many modern words like “helicopter” and “telephone” were derived from Greek words.

Vowels in the ancient Greek language had both pitch-accent and quantity (time value) unlike the stressed syllables of modern Greek. These determinations were made based on the fact that syllables of a line of ancient Greek poetry created prosodic rhythms with the long vowels receiving twice the time value as short vowels.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Introduction to Attic Greek” by Donald J. Mastronarde Amazon.com;

“Greek: An Intensive Course” by Hardy Hansen and Gerald M. Quinn Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Ancient Greek: A Literary Approach” by Cecelia Eaton Luschnig and Deborah Mitchell (2007) Amazon.com;

“Complete Ancient Greek: A Comprehensive Guide to Reading and Understanding Ancient Greek, with Original Texts” by Gavin Betts and Alan Henry (2012) Amazon.com;

“Language and Society in the Greek and Roman Worlds” by James Clackson (2015) Amazon.com;

“Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction” by Benjamin W. Fortson IV Amazon.com;

“Writing Greek: An Introduction to Writing in the Language of Classical Athens”

by John Taylor and Stephen Anderson (2011) Amazon.com;

“Greek Writing from Knossos to Homer: A Linguistic Interpretation of the Origin of the Greek Alphabet and the Continuity of Ancient Greek Literacy” by Roger D. Woodard (1997) Amazon.com;

“Letter Perfect: The Marvelous History of Our Alphabet From A to Z” by David Sacks (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Decipherment of Linear B” by John Chadwick (1958) Amazon.com;

“The Man who Deciphered Linear B: Michael Ventris” by W. Andrew Robinson (2002) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to the Ancient Greek Language” by Egbert J. Bakker Amazon.com;

“Forty-Six Stories in Classical Greek (Ancient Greek and English Edition)” by Anne H. Groton, James M. May Amazon.com;

Indo-Europeans and Indo-European Languages

The Greeks were Indo-Europeans. Around a 3000 B.C., during the early Bronze Age, Indo-European people began migrating into Europe, Iran and India and mixed with local people who eventually adopted their language. In Greece, these people were divided into fledgling city states from which the Mycenaeans and later the Greeks evolved. These Indo European people are believed to have been relatives of the Aryans, who migrated or invaded India and Asia Minor. The Hittites, and later the Greeks, Romans, Celts and nearly all Europeans and North Americans descended from Indo-European people.

Indo-Europeans is the general name for the people speaking Indo-European languages. They are the linguistic descendants of the people of the Yamnaya culture (c.3600-2300 B.C. in Ukraine and southern Russia who settled in the area from Western Europe to India in various migrations in the third, second, and early first millenniums B.C.. They are the ancestors of Persians, pre-Homeric Greeks, Teutons and Celts. [Source: Livius.com]

The Indo-European group of languages is a language family that originated in western and southern Eurasia. It includes most of the languages of Europe as well as ones from northern Indian subcontinent and the Iranian English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Danish, Dutch, Spanish, Hindi, Farsi, Greek, Italian are all Indo-Europe languages. The Indo-European family is divided into several branches or sub-families, of which there are eight groups with languages still alive today: Albanian, Armenian, Balto-Slavic, Celtic, Germanic, Hellenic, Indo-Iranian, and Italic. An additional six subdivisions are now extinct. [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Article INDO-EUROPEANS factsanddetails.com; INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES europe.factsanddetails.com

How Scholars Work Out What Ancient Greek Sounded Like

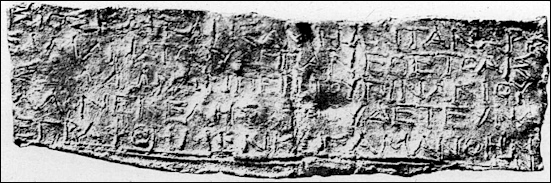

Linear A tablet

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: One way philologists investigate how spoken words were pronounced in antiquity is by tracing changing spellings, especially in non-elite texts. “In popular texts, spelling is more likely to be adapted to the sound of the word and less likely to be tethered to some conservative idea of ‘proper’ spelling,” says classicist Tim Whitmarsh of the University of Cambridge. Another approach involves looking at surviving texts of all kinds, including poetry, to identify what they might reveal about how people spoke. Whitmarsh recently examined artifacts found across the Roman Empire, including 20 gemstones and a graffito on painted plaster in a house in Cartagena, Spain, all of which contain a popular short poem written in Greek. His conclusions may provide scarce direct evidence of a particular way that people spoke — one that persists in English and many other languages today — centuries earlier than previously known. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, March/April 2022]

“Before the Middle Ages, many poetic traditions of the ‘classical’ cultures, such as Greek and Latin in what is now Europe, and Arabic and Persian further east, used a form of verse that was entirely different from anything we know of as poetry today,” Whitmarsh says. Up to that time, poems followed the rules of classical meter in which the meter, or rhythm, of a poem is determined by the length of time it takes to say the verse’s long and short syllables. “Think ‘hope’ versus ‘hop,’” says Whitmarsh. This regular pattern of short and long syllables is known as quantitative meter, and differs from the qualitative, or stressed, meter of the Middle Ages and beyond. As an example of the latter, try reciting “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” and note how some syllables are stressed — the “twin” in “twinkle,” “li” in “little,” and “star,” — or “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” where “Mar,” “ha,” “li,” and “lamb” are stressed.

Previously, scholars agreed that the earliest unambiguous examples of stressed poetry are works composed by the hymnist Romanos the Melodist in the mid-sixth century A.D. But Whitmarsh suggests that the inscribed poem he has been studying, which dates to the second or third century A.D., was recited in stressed meter. This would mean people in the Greek-speaking Roman Empire were accustomed to stressed speech centuries earlier than previously thought. “This way of speaking must have been bubbling around in the oral tradition,” says Whitmarsh. “Romanos wrote hymns using the stressed accent not to innovate spectacularly, but to plug in to the way normal people were speaking. This is a rare glimpse of how people actually sounded.”

Whitmarsh also believes the widely recited poem is evidence of an extraordinary crossover between popular culture and the written word in the form of a fashion statement. “From Spain to Iraq, everyone wants this little gemstone and its poem,” he says. The poem remained remarkably consistent through time and across the empire’s vast expanse, and seems to have appealed to a literate, but not especially high-status, sort of person. The gemstones are made of glass paste and the language is vernacular and includes no adjectives or nouns. “It’s about as simple as you can get,” says Whitmarsh. “It’s a kind of playground chat that starts in the middle of a conversation and has an easily reproducible rhythm that sounds like the main verse of Chuck Berry’s ‘Johnny B. Goode.’” There was also an economic dimension to the poem’s popularity and reach. “The Roman Empire produced wealth and opportunity that people had never had before and the chance to buy into culture and to travel and network in a way never before possible,” he says. “This object spread like wildfire because the empire was an information superhighway.”

Ancient Greek Written Language

According to the ancient Greeks they adapted their alphabet from the Phoenicians. Both were great seafaring peoples and eager to trade not only goods but ideas. One of the most important ideas was the alphabet. It enabled a system of writing by which they could record their transactions- 100 jars of olive oil, 20 blocks of white marble, 30 packages of purple dye, etc. As with other ideas they borrowed the Greeks made improvements, increasing the number of letters by adding vowels. This happened sometime around the beginning of the eighth century B.C. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

“This was not the first time that Greek speaking peoples had used a written language. The Mycenaeans, who were the subjects of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, had developed a system of writing that today's scholars call “Linear B”. Several thousand sun-dried clay tablets covered with the Linear B script have been found on the island of Crete. They represent the earliest form of written Greek known. Deciphered by a young English architect (Michael Ventris), the tablets recorded details about the storage and distribution of household goods. The information was probably written around 1400 B.C. . Then, during the Dark Age, the knowledge of writing died out. The Greeks became an illiterate society. |

“With the adoption and modification of the Phoenician alphabet the Greeks were on their way to becoming literate again. In fact the achievements for which they became renowned in fields as varied as philosophy, science, government, literature and medicine would not have happened if it weren't for writing. Socrates wrote nothing but we know so much about what he thought and said because of the writings of Plato. Access to a simple writing system meant that everyone willing to learn could, in theory, do so –women, slaves, peasants as well as members of the aristocracy. In fact, however, most didn't and illiteracy was widespread during the golden age of Greece- the Classical Era. |

“The Mycenaean Greeks used sharp instruments to engrave their language into wet clay tablets. (A major fire at an ancient palace baked thousands of these tablets and preserved them for scholars today.) Later Greeks used a variety of writing implements- papyrus (which they got from Phoenician traders), parchment (which was made from the scraped hides of cattle, ship or goats), wooden tablets whitened with gypsum, wooden tablets coated with wax and, of course, more durable materials such as stone monuments and bronze plaques. These more permanent materials were often used for official inscriptions- laws of the city, treaties with other states, temple dedications, war memorials and such. |

“Early Greek writing runs from right to left- for the first line. The second line then runs from left to right and the direction of the lines alternate for the complete text. This kind of writing is called boustrophedon (as the ox turns- when he plows a field.) Later the left to right system, which we use today, became the standard.”

Minoan Language

Minoans were the first Europeans to use writing. Their written language was only deciphered in the late 1990s. Known as Linear A, it contains 45 "letters" and is categorized as an ancient form of Greek. The few scraps of Minoan text that have been translated are mainly records of trade, inventories of military equipment, and lists of harvests of wheat and olives. Linear A clay tablets, dated between 1900 and 1700 B.C., were found at Knossos. They were found along with tablets with Minoan hieroglyphics, Linear B, and a still undeciphered Cretan script dated to 2000-1700 B.C.

The Phaistos Disk, found in the ruins of the 3700-year-old B.C. palace of Phaistis, is the earliest know example of printing. The six-inch, baked-clay disk contains 241 pictorial designs comprised of 45 different letters arranged in a spiral formation. The symbols were placed on the disk with a set of punches, one for each symbol, using the same concept as movable type.

The ancient Mycenaeans had a written language in 1200 B.C., called Linear B, that was discovered on clay tablets at Mycenaean and Minoan sites. Tablets found in 1939 at Pylos by American archaeologist Carl Blegen and deciphered in 1940 by an eighteen-year-old young Englishman named Michael Ventris, who revealed his discovery in a 1952 BBC interview and also revealed that the language was a precursor of Greek and the was oldest written Indo-European language known. See Below

See Separate Article: MINOAN WRITING: LANGUAGES. HIEROGLYPHICS, LINEAR A europe.factsanddetails.com

Linear B

The ancient Mycenaeans had a written language in 1200 B.C., called Linear B, that was discovered on clay tablets at Mycenaean and Minoan sites. Tablets found in 1939 at Pylos by American archaeologist Carl Blegen and deciphered in 1940 by an eighteen-year-old young Englishman named Michael Ventris, who revealed his discovery in a 1952 BBC interview and also revealed that the language was a precursor of Greek and the was oldest written Indo-European language known.

_4th_Century.jpg)

Magic Pella leaded tablet (katadesmos) 4th Century

These where startling revelations when one considers that no one had any idea what language the Mycenaeans spoke, that written Greek didn't reappear until 400 years later in the 5th century B.C. and that the Greek alphabet and the Mycenaean symbols looked as different from one another as Chinese and English.μ

Blegen found 1,200 clay tablets, which had been preserved in a palace fire in 1200 B.C. He determined that Linear B there was used primarily to record palace inventories and administrative records of thing like olives, wine, chariot wheels, tripods, sheep, oxen, wheat, barely, spices, plots of land, chariots, slaves, horses and taxes to be collected. So far no references to the Trojan War or anyone mentioned in the “ Iliad” have been found in Linear B.

See Separate Article: MYCENAEAN CULTURE AND LIFE: SOCIETY, ART, LINEAR B europe.factsanddetails.com

Expressions and Names in Ancient Greece

The expression "big fish eat little fish" has been traced by to the Greek poet Hesiod, who wrote it in the 8th century B.C. It probably originated much earlier, possible in Mesopotamia.

The expression "Don't count your chickens before they are hatched" is attributed to Aesop in 570 B.C. In the story “ The Milkmaid and her Pail” , Patty the farmer's daughter says, "The milk in this pail will provide me with cream, which I will make into butter, which I will sell at the market, and buy a dozen eggs, and soon I shall have a large poultry yard. I'll sell some of the fowls and buy myself a handsome new gown."

The expression "he who fights and runs away will live to fight another day" was attributed to the Athenian orator and statesman Demosthenese who fled a battle between Athens and Macedonia, in which 3,000 Athenians died, and was later censured for desertion. He reportedly used the expression whenever someone accused him of being a coward.

Dodona curse inscription

Among the expressions collected by the poet-philosopher Heraclitus are: 1) “You can’t step twice into the same river;” 2) “Souls smell in Hades;” 3) “The eye, the ear, the mid in action, these I value;” 4) “goat cheese melts and warm wine congeals if not well stirred.”

Book: “ Fragments: the Collected Wisdom of Heraclitus” (Viking, 2001)

In ancient times people generally only had one name, which was given at birth. People with the same name were often differentiated from one another by identifying them as the son of someone (i.e. James, the son of Zeledee in the Bible) or linking them to their birthplace (i.e. Paul of Tarsus, also from the Bible).

Differences Between Classical and Hellenistic Greek

On the difference between Koiné (or Hellenistic) Greek and Classical Greek, Jay C. Treat, of the University of Pennsylvania wrote: A.T. “Robertson characterizes Koiné Greek as a later development of Classical Greek, that is, the dialect spoken in Attica (the region around Athens) during the classical period. For all intents and purposes the vernacular Greek is the later vernacular Attic with normal development under historical environment created by Alexander's conquests. On this base then were deposited varied influences from the other dialects, but not enough to change the essential Attic character of the language (Robertson, 71). If the Koiné is an outgrowth of Classical Greek, what are the differences between the two? Robertson states the basic differences succinctly. Koiné was more practical than academic, putting the stress on clarity rather than eloquence. Its grammar was simplified, exceptions were decreased and generalized, inflections were dropped or harmonized, and sentence-construction made easier. Koiné was the language of life and not of books. [Source: Jay C. Treat, University of Pennsylvania, ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~jtreat, Last modified: August 03, 2015 ]

“Orthographic changes are relatively minor. Attic tt usually becomes ss. There is a tendency to change rough breathing to smooth breathing, except in words that once contained a digamma (or words used in analogy with them). Elision is not as common in the Koiné but there is even more assimilation than in Classical usage. There is less concern for rhythm. The -μ forms are beginning to drop out. The movable consonants in “t” and “st” are added regardless of whether the next word begins with a vowel, as Classical usages required. Accent by pitch gives way to accent by stress. Changes in vocabulary are of course too numerous to list here. Generally, it may be said that there are many shifts in the meaning of words and in the frequency of their usage.

“There are many differences between Classical Greek and Koiné in syntax. Koiné has shorter sentences, more parataxis and less hypotaxis, a sparing use of participles, and a growth in the use of prepositions (although some old ones have died out). Variations of nouns, adjectives, and verbs are often according to sense, and a neuter plural substantive may be used with either a singular or a plural verb. Koiné used personal pronouns in oblique cases much more often, whereas writers in Attic used them only when they were necessary for clarity.

“In Classical Greek there were five types of conditional sentences (using Blass's classification): 1) real conditions (e? with the indicative), 2) contrary-to-fact conditions (e with an augmented tense of the indicative), 3) conditions of more vivid expectation, 4) conditions of less vivid expectation, and 5) repetition in past time. In Koiné, type 1 (real conditions) has lost ground, type 2 (contrary-to-fact conditions) persists, type 3 (more vivid conditions) prevails, type 4 (less vivid conditions) is barely represented, and type 5 (repetition in past time) has disappeared. One Classical feature that Koiné does not have is the conditional relative clause."

Derveni Papyrus with Greek writing

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024