Home | Category: Alexander the Great

ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S MILITARY LEADERSHIP

Wall painting in Acre Alexander the Great (356 to 324 B.C.) was a superb military commander. Believing himself invincible and specially blessed by the gods, he often led the cavalry charges himself, which often proved decisive, and often wore an easy-to-spot white-plumed helmet. He suffered severe sword, lance, arrow and knife wounds. Alexander once told his men, "There is no part of my body...which has not a scar...and for all your sakes, for your glory and your gain."

“As a warrior and a strategist, no one compares with Alexander,”Alexander biographer Lane Fox told Smithsonian magazine, “He would have made mincemeat of any Roman who came over the hill. Julius Caesar would’ve gone straight back home as fast as his horse could carry him.” And Napoleon — “Alexander would’ve wiped him out too. Napoleon only fought dodos.”

Alexander had full confidence that his men would follow him. Admiral Ray Smith, a former Navy SEAL told National Geographic, "We have learned that the key to leadership under the toughest possible circumstances is that officers and men undergo the same training. Men know their officer is not asking them to do anything he couldn't do or hasn't done."

Arrian wrote: “The sheer pleasure of battle, as other pleasures are to other men, was irresistible” to Alexander. Once, while fighting at a fortress in Multan, in present-day Pakistan, Alexander found himself stranded without a ladder. Instead of leaping outside the walls to safety he jumped inside where he was surrounded by enemies and fought off his attackers until help arrived. During the clash he sustained a nearly fatal arrow wound that may have punctured his lung. When doctors insisted that officers hold him down to prevent him from squirming while they removed the arrow head Alexander insisted that wasn’t necessary and lay still as doctors cut deeply into his chest to remove the embedded weapon.

Alexander also showed great compassion for his men. "For the wounded he showed deep concern," wrote Arrian. "He visited them all and examined their wounds, asking each man how and in what circumstances his wound was received, and allowed him to tell his story and exaggerate as much as he pleased."

Categories with related articles in this website: Ancient Greek History (48 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Art and Culture (21 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Life, Government and Infrastructure (29 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden–Sydney College, Virginia hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ; Ancient-Greek.org ancientgreece.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; The Ancient City of Athens stoa.org/athens; The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT rtfm.mit.edu; 11th Brittanica: History of Ancient Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ;Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu

Alexander's Army and Weapons

hoplite Alexander’s army was made up of around 50,000 men (an enormous number at that time when great cities had a population of 10,000 or 20,000). Most were Macedonians or hired Greek mercenaries that were paid in booty from the conquests. As time went on the Greeks were dropped and the army was made up mostly of Macedonians or subjects of the most recently conquered territory. Cambridge historian Nicholas Hammond told National Geographic, "Alexander kept his army supplied by recruiting from the enemy. The fact that he could successfully do this speaks volumes about his leadership."

Alexander’s force is regarded as the first professional army. At the vanguard were the Companions, an elite highly-skilled cavalry force, and the Macedonian phalanx, a high mobile unit of foot soldiers with long pikes. Cavalry made up about a sixth of the army. The Macedonians had a much more developed cavalry than the Greeks in part because Macedonia had more grasslands to feed horses. Genghis Khan and Alexander had similar-sized armies.

Among the foot soldiers were archers, equipped with short bows; Greek hoplites, skilled veteran soldiers; shield bearers, who carried weapons and assisted the hoplites; slingers, who threw stones with slings; and trumpeters who relayed messages on the battlefield.

Supplying an army of 50,000 men was no easy task. Alexander employed bullocks and oxen (young and old castrated bulls) to carry the supplies, and the tactical range of his army was eight days, the maximum length of time in which an ox can carry supplies and food for itself. Campaigns of longer duration had to stay near ports (where food could delivered) or at settlements that were large enough to supply Alexander's army with what it needed. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Alexander’s soldiers relied on the “sarissae”, or pike, a 4.3-meter-long spear that was twice as long as a standard spear. Archers used powerful short bows. Slingers threw stones to harass the enemy. Soldiers were armed with swords and wore armored helmet and breastplate like the Greeks and used a round shield for protection. The cavalry rode horses with rudimentary saddles with no stirrups.

While the Persians and others relied on long bows the Greeks amd Macedonians were primarily hand-to-hand combatants who relied on swords and thrusting pikes. Sarissae were wooden pikes. They were generally around three meters longer than the average spear and this gave them a range advantage.

Alexander the Great’s Military Tactics

Alexander liked to strike quickly. Some credit him with perfecting the cavalry charge. He often ignored the advise of his generals who advised caution and seemed little worried if his enemies held the high ground or some other advantageous military position.

At the heart of Alexander’s army were rows of disciplined soldiers with pikes, spears and swords that were organized into a “phalaiazn” and were capable of overpowering far larger enemy groups. The front rows were armed with sarissaes which had a longer reach than their opponents. Rear troops pushed forward and helped the front-row troops press ahead. Archers, slingers and cavalry attacked and defended the sides.

Foot soldiers in Alexander the Great's army learned to withstand chariot advances by aiming their weapons at the horses first: by employing arrow-proof armor and shields; and by organizing themselves into tight chariot-proof ranks.

Alexander conducted at least 20 sieges, but none within Persia because the empire was supposedly guarded from its perimeter. The three main battles — Granicus, Issua and Guagamale — were fought in open country.

Alexander relied heavily on spies. He also purportedly spied on his own soldiers by intercepting their outgoing mail. According to legend, Alexander was the first commander to require that all of his soldiers be cleanly shaven. This was so that enemies could have nothing to hold on to. ◂

Civilians were often targeted, especially in Lebanon and the Indus Valley, where large number of innocent people were killed for no military reason. The historian Ernst Badian told National Geographic, "Blood was the characteristic of Alexander's whole campaign. There is nothing comparable in ancient history except Caesar in Gaul."

Alexander the Administrator

Family of Darius before

Alexander by Paolo Veronese, 1570 Alexander showed some skill as an administrator. He tolerated local customs and appointed local administrators. He appointed Persians to many posts and adopted the Persian style of administration even though Persians had long been his sworn enemies. He even wore local clothes of the Persians to earn support of the Persian people, something the soldiers that fought under him took offence to.

Administrative realities sometimes clashed with codes that kept military moral high. Alexander welcomed some Persians into his inner circle and even ordered a royal funeral for his main adversary, Darius III. These moves infuriated some of Alexander’s soldiers and paved the way for a mutiny. Green wrote in his biography “Alexander of Macedon” “the sight of their young king parading in outlandish robes, and in intimate terms with the quacking, effeminate barbarian nobles he had so lately defeated, filled [his troops] with disgust.” Alexander also angered those close to him by ordering the death of Parmenion, a loyal and venerated general who fought under Phillip and Alexander. and Callisthenes, Aristotle's nephew.

When Alexander learned that soldiers were plotting to kill him, he arrested seven of the alleged conspirators, including Philotas , the son of Parmenion. Although the evidence against Philotas was weak he and the others were stoned to death. In a pre-emptive move to stem a revenge attack, Alexander also had the 70-year-old Parmenion stabbed to death. From then on “Alexander never trusted his troops,” Green told Smithsonian magazine, “The feeling was mutual.”

Alexander the Great’s Death

Alexander died just short of his 33 birthday on June 10, 323 B.C. The cause of his death is unknown. In some accounts he drank a huge amount of wine at a banquet and collapsed with a fever. In other accounts he became sick, perhaps with malaria, on his way back from India. Most scholars believe that was a major factor in his death. In Susa a fakir brought from India had prophesied Alexander's death.

In early 323 B.C., Alexander entered Babylon to prepare for an Arabian expedition. At a banquet he was seized with abdominal pains and was forced to retire to his quarters. He then came down with a fever and was so ill and soon he couldn't speak or move. Alexander was ill for two weeks before he died.

Before his death, Alexander's troops, concerned he was already dead, demanded to see him. Arrian wrote: "Nothing could keep them from the sight of him, and the motive in almost every heart was grief of a sort of helpless bewilderment at the thought of losing their king. Lying speechless as the men filed by, he struggled to raise his head, and in his eyes there was a look of recognition for each individual he passed.”

Some have suggested Alexander died of pancreatitis, alcoholism aggravated by a broken heart over death of his lover, Hephaestion, war wounds, a perforated ulcer, leprosy, syphilis, typhoid, panic, West Nile virus, an infected monkey bite, or even murder by poison. One scholar argued that a perforated bowel — which can cause paralysis and make one look dead before they actually die — could explain the legend that his body did not begin composing until days after his 33rd birthday,

Alexander’s symptoms included a fever, thirst, abdominal pain and paralysis. His symptoms match up well with West Nile virus encephalitis. There were stories that birds dropped dead at his feet when he entered Babylon. West Nile virus encephalitis was not identified until 1937 but is thought to have been around much longer than that. some scholars believe he may have had typhoid-induced ascending paralysis which also makes one look dead before they actually die.

Alexander’s Sarcophagus?

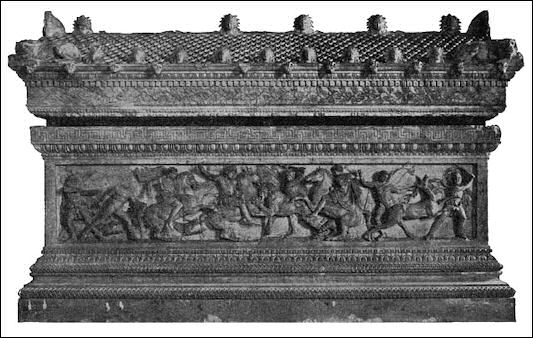

Tomb of Alexander the Great

Ptolemy I Soter (304-283 B.C.) took control of Egypt after Alexander the Great died. He was an ambitious self-made Macedonian general who served under Alexander and was also known as Ptolemy the savior. Ptolemy was crowned pharaoh in 304 B.C. on the anniversary of Alexander's death. He made offerings to the Egyptian gods, took an Egyptian throne name, and portrayed himself in pharaonic garb.

When Alexander died Ptolemy somehow got his hands of Alexander's embalmed corpse (some say he stole it as it was being shipped back to Macedonia for burial). The body had been embalmed with honey. Ptolemy put the corpse in class coffin and had it displayed to the public. [Source: Lionel Casson, Smithsonian magazine, June 1985]

Ptolemy brought Alexander’s body to the northern coat of Egypt to shore up his claim on the region and boost his legitimacy. Ptolemy made Alexander’s tomb into one of the world’s first major tourist attractions and through it brought recognition to Alexandria. The corpse was exhibited in an elaborate mausoleum much as the bodies of Lenin and Mao are displayed in class cases in Moscow and Beijing. Tourist reportedly formed long lines to glimpse the famous Macedonian general's embalmed body. The body is thought to have remained there for six centuries and is thought to have maybe disappeared in riots in the A.D. 3rd century.

In February 1995, Greek archaeologist Liana Souvalzi claimed she had discovered the tomb of Alexander the Great at the Siwa Oasis in Egypt (near the Libyan border), 1,200 miles away from where the Macedonian general died in Babylon. Ruined by an ancient earthquake, the tomb consists of a 12-by-12 foot burial chamber with two antechambers and a corridor flanked by statues of two lions. The tomb, which is similar to the tomb of Alexander's father, Philip II, was identified by a tablet believed to have been written by Ptolemy I, describing how he brought the body from Alexandria.

Colored Alexander sarcophagus

After the announcement a Greek delegation toured the site and said there was no proof to corroborate Souvalzi's claim. A few years later funding of the excavation was stopped. The delegation claimed that what Souvaltzi found may not even be a tomb and that it appeared to have been built more than a century after Alexander's death. Souvaltzi's research was funded by her husband. She once said that she sought advice of where to look for promising site from snakes.

Alexander the Great’s Empire After His Death

When Alexander was on his deathbed he was asked to name a successor. Arrian reported the empire should go “to the strongest. I foresee a great funeral contest over me.” Roxanne and her son, Alexander IV, born six weeks after Alexander’s death were murdered by a distant relative when the boy was 12 or 13. Alexander’s mother Olympias was also killed.

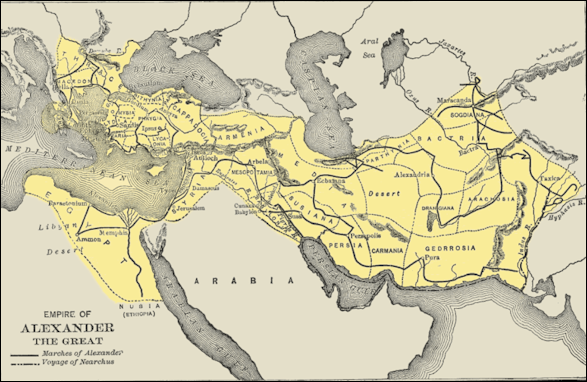

Alexander the Great's million-and-a-half square mile empire lasted for only a few decades after he died, but it spread Greek culture to the corners of the known world at that time and ushered in the Hellenistic period. Arrian wrote that in one of his last speeches to his troops Alexander said "I set no limits of labors to a man of spirit, save only that the labors themselves...lead on to noble enterprises...It is a lovely thing to live with courage, and to die, leaving behind an everlasting renown."↔

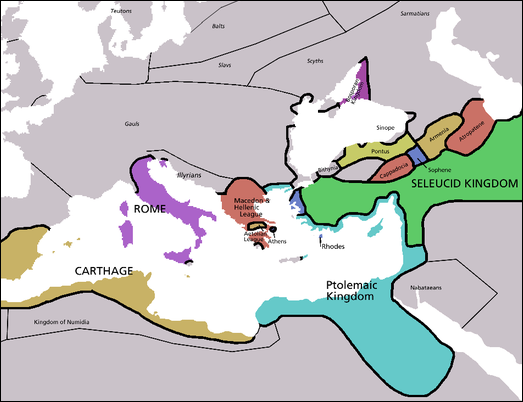

After Alexander died his generals spent 40 years fighting among themselves before three main dynasties merged:the Antigonids of Asia Minor and Greece; the Ptolemies in Egypt (which included Cleopatra); and the Selecuids, who occupied a stretch of land that extended from present-day Syria and Lebanon to Persia.

"Alexander the Great's Empire fell, in part, because he treated his provincial subjects as defeated enemies," wrote journalist T.R. Reid in National Geographic. "The Romans treated their subjects as Romans — not outsiders but contributors."

Alexander's empire

Alexander's Legacy

Although much of Alexander's empire fell part after his death, he is credited with spreading Greek culture far into Asia, which in turn had an affect on government, art, literature and religion in places that had never heard of Greeks before.

Alexander the Great founded 20 cities and unified the East and West. The cities helped disseminate Greek culture. He is also is credited with exposing Greece and the Western to Eastern culture. Some say he helped civilize the Persians, Sogdians and others. Of the six cities established by Alexander only Alexandria remains.

Borcas, the Greek god of the west wind. was adopted by local people and made its way westward as far as Japan, where he became Fujin, the Japanese god of wind. As he moved eastward Borcas exchanged his wings for a veil as he became Vado the wind god in ancient Kushan in Pakistan. Greek-influenced images of the Buddhist gods Vaisravana and Majakala have been found in Pakistan. Images of Greek soldiers have been found in China.

The Kafir-Kalash (Kafir-Kalaish) — a tribe that lives in the Birir, Bumburet and Rambur valleys off of the Chistral Valley in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan — claim they are descendants of five of Alexander the Great's warriors. One of a handful of groups that claim Alexander’s army to be their ancestors, the Kalash relate a story of Alexander's bacchanal with mountain dwellers claiming descent from Dionysus. "They were likely the forbears of the Kalash, who still worship a pantheon of gods, make wine, practice animal sacrifice — and resist conversion to Islam." Although Alexander’s armies passed through the Chitral region there is little evidence that they reached the remote valleys where the Kalash live today.

Whether Alexander the Great is from the present-day country of Greece or the country of Macedonia is a divisive political issue between those two nations. Each claims Alexander as their own. In 2009, Macedonia raised eyebrows when it proposed building an eight-story-high statue of Alexander the Great in the center of its capital Skopje.

Pierre A. Zalloua of the American University of Beirut Medical Center is studying if the armies of Alexander the Great left behind a genetic legacy in places he conquered.

Europe and the Near East After Alexander's Death

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018