Home | Category: Otzi and Copper Age Europe / Minoans and Mycenaeans

CYPRUS—ISLAND OF COPPER

Cyprus copper oxide ingot with Cypro-Minoan sign

Covering 3,570 square miles, Cyprus is situated in the northeastern corner of the Mediterranean Sea, south of present-day Turkey and west of present-day Syria. It is the third largest island in the region after Sicily and Sardinia.Cyprus was famous in antiquity for its copper resources. The word copper in fact is derived from the Greek name for the island, Kupros. The wealth of the island's elites was based on their control of copper ore mines in the Troodos Mountains, in the western part of the island. Copper was alloyed with tin to make bronze, used to make a variety of implements and weapons, making Cyprus source of metal in Copper Age and Bronze Age.

The third-largest island in the Mediterranean, Cyprus, is thought to have been first settled around 8,800 B.C., according to the British Museum, and was the main source of copper during the Bronze Age. There was even a deity known as the Copper Ingot God in Cyprus. A statuette discovered at the archaeological site of Enkomi shows this god a standing on a base shaped like an oxhide ingot. Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Mediterranean traders had access to multiple sources of copper, but researchers have analyzed the Ulu Burun wreck’s copper and found that it all came from Cyprus, an island with vast quantities of the raw material. Although there would have been a Bronze Age without Cypriot copper, it is hard to imagine that it would have transpired in the same way. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, January/February 2024]

“Without any doubt,” University of Gothenburg archaeologist Peter Fischer says, “Cyprus was the main producer of copper during the Late Bronze Age. There is no other area that has such rich copper mines.” Cyprus was also strategically located at the crossroads of the Bronze Age Mediterranean’s greatest cultures, lying 45 miles south of Anatolia, 40 miles west of the Levant, 250 miles north of Egypt, and 340 miles east of Crete. As traders sailed from east to west and north to south, they would inevitably have passed by Cyprus, making it a popular stop for merchants and an ideal emporium.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Archaeology of Cyprus: From Earliest Prehistory through the Bronze Age” by A. Bernard Knapp (2013) Amazon.com;

“Cyprus Before the Bronze Age: Art of the Chalcolithic Period” by Vassos Karageorghis and Edgar J. Peltenburg (1990) Amazon.com;

“Early Cyprus: Crossroads of the Mediterranean” by Vassos Karageorghis Amazon.com;

“Ancient Art from Cyprus: (Metropolitan Museum of Art) by Vassos Karageorghis (2000) Amazon.com;

“Chalcolithic and Bronze Age Pottery from the Field Survey in Northwestern Cyprus” 1992¬-1999 by Dariusz Maliszewski (2013) Amazon.com;

“Journey to the Copper Age: Archaeology in the Holy Land” by Thomas E. Levy and Kenneth L. Garrett (2007) Amazon.com;

“Masters of Fire: Copper Age Art from Israel” by Michael Sebbane, Osnat Misch-Brandl, et al. (2014) Amazon.com;

The Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Ages in the Near East and Anatolia

by James Mellaart (1966) Amazon.com;

“Life in Copper Age Britain” by Julian Heath (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Glacier Mummy: Discovering the Copper Age with the Iceman” by Gudrun Sulzenbacher (2017) Amazon.com;

Cyprus Copper Industry

Colette and Seán Hemingway of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Cypriots first worked copper in the fourth millennium B.C., fashioning tools from native deposits of pure copper, which at that time could still be found in places on the surface of the earth. The discovery of rich copper-bearing ores on the north slope of the Troodos Mountains led to the mining of Cyprus' rich mineral resources in the Bronze Age at sites such as Ambelikou-Aletri. Tin, which is mixed together with copper to make bronze, typically at a ratio of 1:10, had to be imported. [Source: Colette Hemingway and Seán Hemingway, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

ancient kingdoms of Cyprus

“True tin bronzes appear to have been made on Cyprus as early as the beginning of the second millennium B.C. In the nineteenth century B.C., the island is mentioned for the first time in Near Eastern records as a copper-producing country, under the name "Alasia," and it continued to be an important source of copper for the Near East and Egypt throughout most of the second millennium B.C. Scholars, however, are in disagreement as to the exact meaning of "Alasia": whether it refers to a specific site on Cyprus, such Enkomi or Alassa, or to the island itself, or, less probably, to another geographic location. \^/

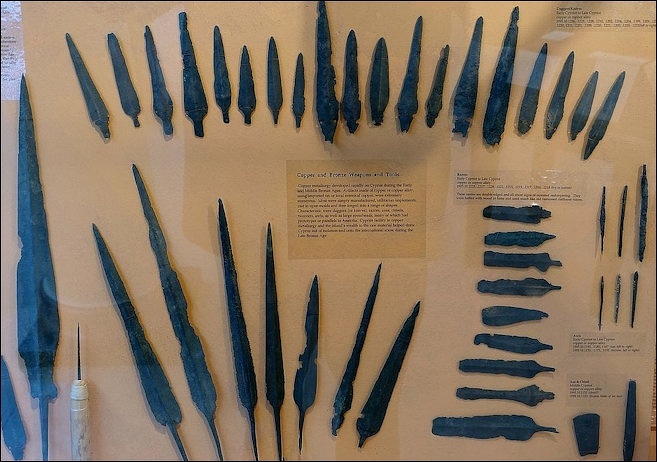

“Cypriot copper and bronze working was relatively modest in the Early and Middle Bronze Ages, and metalsmiths manufactured a limited range of types, including tools, weapons, and personal objects such as pins and razors. Excavations have revealed increasing metallurgical activity at settlement sites in the Late Bronze Age. Nearly all of the major centers, including Enkomi, Kition, Hala Sultan Tekke, Palaeopaphos, and Maroni, provide evidence of copper smelting, as do smaller settlements, including Alassa and Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios. \^/

“Metalwork of the first part of the Late Bronze Age continued to follow earlier conservative traditions. Despite the widespread evidence for metallurgical activity, there are few examples of actual bronzework from Cyprus between ca. 1450 B.C. until the late thirteenth century B.C., the Late Cypriot II period, because the metal was valuable and metal objects were melted down in subsequent periods for reuse. However, the recent discovery of the Ulu Burun shipwreck, which was carrying over ten tons of Cypriot copper ingots when it sank off the southwestern coast of Turkey in the late fourteenth century B.C., vividly demonstrates that Cyprus was a major producer of copper for international trade. Toward the end of the Late Bronze Age, the Cypriot metalworking industry was transformed under foreign influence. Cypriot smiths produced some of the finest bronzework in the eastern Mediterranean, most notably tripods and four-sided stands.” \^/

Good Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Livescience livescience.com/ Iceman Photscan iceman.eurac.edu/ ; Otzi Official Site iceman.it

Ulu Burun Shipwreck

The Ulu Burun shipwreck refers to ship carrying over ten tons of Cypriot copper ingots that sank off the coast of Kas, in southwestern Turkey in the late fourteenth century B.C. Over 1,500 items were found on the ship, including 11 tons of tin and copper ingots, a trumpet made from a ram horn and hippo teeth, African ebony, ostrich eggs, amphoras filled with aromatic tetrbinthine resin, weapons, large quantities of gold and ivory.

The Ulu Burun shipwreck is one of the oldest-known ship wrecks. Archaeological remains indicate that the ship was sailing west, having perhaps called at other harbors in the Levant, and that it had loaded 355 copper ingots in Cyprus, as well as large storage jars, some of them containing fine Cypriot pottery and agricultural goods, including coriander. There was enough copper and tin on board the Ulu Burun ship to produce 11 tons of bronze, which experts estimate could have been turned into 33,000 swords, more than enough to adequately supply a large army.

The Ulu Burun shipwreck was discovered in 1982 by a Turkish sponge diver named Mehmet Çakir in 45-meter (150-feet) deep waters He described numerous “metal biscuits with ears,” which archaeologist recognized as a type of metal bar known as an oxhide ingot that was commonly traded during the Bronze Age, 3,500 years ago. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, January/February 2024]

The discovery caught the attention of Anatolian archaeologists. Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Authorities immediately began to search for the site, and soon came across the artifacts that Çakir had spotted not far offshore of Ulu Burun, or the Grand Cape. In addition to the ingots, there were so many other ancient objects scattered about that archaeologists and divers would spend a decade returning to the site. It would take them more than 22,000 separate dives to retrieve all the artifacts from what is one of the world’s oldest and most spectacular shipwrecks.

In many ways, the Ulu Burun wreck represents a microcosm of the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1650–1150 B.C.) world from which it came. This was a time when mariners and merchants crisscrossed the sea on journeys spanning hundreds, even thousands, of miles. In all, about 18,000 objects have been found at the Ulu Burun wreck, and together they weigh more than 17 tons. Among them are elephant tusks, hippopotamus teeth, faience and glass beads, and gold and silver jewelry, as well as weapons and musical instruments. There are artifacts belonging to seven different cultures, including Egyptian, Nubian, Assyrian, and Mycenaean. “The Late Bronze Age is the first international period of the Mediterranean Sea,” says Fischer. The overwhelming majority of the Ulu Burun wreck’s cargo, however, consisted of one particularly desirable commodity: copper. The ship was transporting an astounding 10 tons of the invaluable metal, which is one-third the amount of copper it took to create the Statue of Liberty.

Purple Dye and Copper Making at Hala Sultan Tekke in Cyprus,

Murex snail shells found in the workshops of Hala Sultan Tekke — an archaeological site on the southern coast of Cyprus — were the source of a purple dye that was used in the production of purple-dyed textiles and was one of the ancient world’s most luxurious commodities. Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: For thousands of years, from the Bronze Age through the end of the Roman Empire, purple dye was one of the rarest commodities in the world. It was the color of kings, emperors, and the upper classes. The process of extracting the dye from the mucus gland of the murex sea snail was extraordinarily time consuming, and some experts have estimated that it took as many as 10,000 murex snails to produce a single gram of dye. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, January/February 2024]

At Hala Sultan Tekke, archaeologists have unearthed workshops containing heaps of crushed murex shells, as well as vats used to dye textiles, including one that still has tinges of purple. Loom weights, spindle whorls, and other evidence indicate that textiles were manufactured on-site. “First you need to produce the purple dye, then the fibers for the textiles, then the textiles themselves, and then you need to dye them,” says Fischer. “It’s quite a long process and very expensive.”

Hala Sultan Tekke’s other major industry and its raison d’être was producing and refining copper. One of the world’s greatest sources of copper was the Troodos Mountains, only 25 miles to the west of Hala Sultan Tekke. The evidence for copper production in the city is ubiquitous––there are remnants of furnaces, molds, crucibles, and tuyeres, a kind of metal tube or nozzle through which air is blown into a furnace. Fischer’s team has collected more than a ton of copper slag and ore, as well as discarded bronze objects that were being prepared for recycling. The city’s inhabitants, then, had access to both copper mines and a protected harbor from which to trade their coveted resource. The only question was, could they keep up with the demand from the ships that landed on their shores?

Some of the more than one ton of copper slag and ore uncovered in Hala Sultan Tekke thus far hints at the scale of the city’s copper industry. A copper oxhide ingot excavated at the Bronze Age site of Enkomi on Cyprus resembles ingots found at the Bronze Age Ulu Burun shipwreck, which sank off the southwestern coast of Turkey.

Trade in Prehistoric Cyprus

Colette and Seán Hemingway of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The unique geographic location of Cyprus at the crossroads of seafaring trade in the eastern Mediterranean made it an important center for trade and commerce in antiquity. Already in the Early Bronze Age (ca. 2500 B.C.–ca. 1900 B.C.) and Middle Bronze Age (ca. 1900 B.C.–ca. 1600 B.C.), Cyprus had established contacts with Minoan Crete and, subsequently, Mycenaean Greece, as well as with the ancient civilizations of the Near East (Syria and Palestine), Egypt, and southern Anatolia.[Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“From the first part of the second millennium B.C., Near Eastern texts referring to the kingdom of "Alasia," a name that is most likely synonymous with all or part of the island, attest to Cypriot connections with the Syro-Palestinian coast. Rich copper resources provided the Cypriots with a commodity that was highly valued and in great demand throughout the ancient Mediterranean world. Cypriots exported large quantities of this raw material and other goods, such as opium in Small Base Ring Ware jugs resembling the capsules of opium poppies in exchange for luxury goods such as silver, gold, ivory tusks, wool, perfumed oils, chariots, horses, precious furniture, and other finished objects. \^/

“During the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1600 B.C.–ca. 1050 B.C.), copper was being produced and exported on a massive scale, and Cypriot trade expanded to include Egypt, the Near East, and the Aegean region. Correspondence between the pharaoh of Egypt and the king of Alasia, dating from the first half of the fourteenth century B.C., provides valuable information about the trade relations between Cyprus and Egypt. The Cesnola Collection has a number of objects of faience and alabaster that were imported into Cyprus from Egypt during this period. The scope of Cypriot maritime trade at this time is best exemplified by the fourteenth-century B.C. shipwreck at Ulu Burun recently excavated off the southwestern coast of Anatolia. Archaeological remains indicate that the ship was sailing west, having perhaps called at other harbors in the Levant, and that it had loaded 355 copper ingots (ten tons of copper) in Cyprus, as well as large storage jars, some of them containing fine Cypriot pottery and agricultural goods, including coriander. \^/

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: As ships sailed to Cyprus seeking copper, they brought with them exotic luxury objects from their homelands and others they picked up along the way. Archaeologists have unearthed hundreds of imported ceramic vessels from the Mycenaean and Minoan worlds, as well as pottery from Anatolia, the Levant, Sardinia, and Egypt. There are semiprecious gems and stones, including lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, carnelian from India, and amber from the Baltic. Other objects include cylinder seals from Mesopotamia, silver pendants from Anatolia, turquoise from the Sinai Peninsula, and elephant and hippopotamus ivory objects from Egypt. Perhaps most impressive is an assortment of Egyptian gold jewelry. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, January/February 2024]

Enkomi — Cyprus’s Lost City of Copper?

“To the King of Egypt, my brother. Thus says the King of Alashiya, your brother: ... Send your messenger along with my messenger quickly and all the copper that you desire I will send you.” Dating to 1375 B.C., this passage comes from a collection of tablets known as the Amarna Correspondence, a cache of diplomatic exchanges discovered in the late 19th century. Historians identify the king of Egypt as Akhenaten, but who was writing to him? And where was Alashiya? [Source: María Teresa Magadán, National Geographic History, March-April 2017]

Many historians feel that the most likely candidate for copper-rich Alashiya is an archaeological site near the modern-day Cypriot village of Enkomi. María Teresa Magadán wrote in National Geographic History: ““It is now known that during the Late Bronze Age, from the 15th to 11th centuries B.C., the Enkomi site was one of Cyprus’s significant cities, a center of the copper trade, which was the island’s main source of wealth. Unlike the nearby ancient city of Salamis whose Roman ruins stand to this day (not to be confused with the Island of Salamis just west of Athens), few traces of the ancient site now known as Enkomi remained.

Enkomi ruins in Cyprus

French archaeologist Claude F. A. Schaeffer and Porphyrios Dikaios, curator and later director of the Cypriot Department of Antiquities, established that the necropolis developed in and around a bustling ancient city, which peaked between 1340 and 1200 B.C. Surrounded by a wall built using the “cyclopean” technique of massive stone blocks, it consisted of dwellings, temples, and workshops where copper was processed and bronze items produced. “So was Enkomi the principal city of the copper-rich Alashiya mentioned in the Amarna Correspondence? In 1963 the discovery there of a bronze statuette of a divinity standing on a copper ingot seemed to support this theory.

In 1974 Cyprus was invaded by Turkey, who occupied the northern part of the island — a disputed situation that continues to this day. Schaeffer’s successor, Olivier Pelon, who had taken over in 1970, was forced to suspend the dig. Since then, while most historians believe Cyprus is indeed the Alashiya of antiquity, new research has called into question Enkomi’s status as a “capital” or principal city of this wealthy state.

“To judge from the large range of exquisite objects in museums such as the British Museum, however, Enkomi must have been a sophisticated urban center. Around the 11th century B.C., the city was abandoned while the city of Salamis rose to prominence, becoming the principal Cypriot trading center with Egypt and the rest of the eastern Mediterranean.

Archaeological digs at Enkomi brought hundreds of objects of exquisite craftsmanship to light. Discovered in the city's tombs and sanctuaries, most of the items are now on display in the British Museum, London, and in the Cyprus Museum, Nicosia. They include: 1) a silver cup decorated with gold details in the shape of bucrania and lotus flowers (14th century B.C); 2) an ivory mirror handle showing a warrior fighting a gryphon with an eagle’s head and a lion’s body (13th century B.C.); 3) a pastoral vessel with a bird removing a tick from a bull’s neck (13th century B.C.); 4) a gold diadem with Mycenaean-influenced embossed plant motifs (14th century B.C.) And 5) a bronze “ingot god,” named for the ox-hide shaped ingot of copper on which it stands (12th century B.C.)

Cyprus and the Bronze Age Collapse Around 1200 B.C.

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: The prosperity that Hala Sultan Tekke enjoyed, as well as the success of many other major settlements and cultures of the Late Bronze Age, came to a crashing halt in the twelfth century B.C. when city-states and kingdoms across the Eastern Mediterranean suddenly declined sharply. Among these were Mycenae and Pylos in Greece, Hattusha in Anatolia, and Ugarit in the northern Levant. Eventually, the powerful Hittite Empire disintegrated, while even mighty Egypt lost territory and suffered economic setbacks. Perhaps most significantly, the prosperous cross-cultural trade that had come to epitomize the Late Bronze Age all but ceased to exist. Hala Sultan Tekke was destroyed twice during this period: first around 1200 B.C., and again around 1175 B.C. The city’s inhabitants initially tried to rebuild, but after the second sack, they abandoned the site, never to return. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, January/February 2024]

Most scholars agree that the reasons for the Bronze Age collapse are nuanced and complex, the result of several devastating events, including a series of calamitous earthquakes, that occurred around the same time. There were movements of people and invasions around the Eastern Mediterranean that disrupted trade and the status quo, but they may have been more a symptom than the cause of the collapse. “The Sea Peoples are a phenomenon,” says Fischer. “There were people involved, but at the same time, in the twelfth century B.C., we have indisputable sources talking about epidemics, pestilence, famine, and a worsening climate.”

Copper and bronze weapons and tools from Cyprus

There is little consensus among scholars as to what exactly brought about this catastrophic collapse. Since the nineteenth century, many have blamed a mysterious group of marauders known as the Sea Peoples. Some historians and archaeologists have posited that this group, perhaps originating in Italy, Southern Europe, or the Balkans, suddenly migrated into the Eastern Mediterranean en masse and created havoc by ransacking coastal communities and crippling established political and economic systems. The question of whether the Sea Peoples actually existed remains controversial, although there is some archaeological evidence that they did. For example, the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses III (reigned ca. 1184–1153 B.C.) is said to have fought against and defeated the Sea Peoples in two battles, one on land and the other at sea, which are commemorated on a relief in his temple at Medinet Habu.

As for Hala Sultan Tekke, the city was clearly ravaged, likely by outsiders. “I’m quite convinced the site was attacked,” Fischer says. “It could have been from an angry neighbor, but I tend to blame invading foreigners.” These incursions, along with the silting up of the harbor, which may have happened around the same time, were insurmountable obstacles to its continued success. Hala Sultan Tekke was no longer able to maintain its role as a major trading port, ending a nearly 500-year period of prosperity. According to Fischer, some of the city’s population may have followed the mysterious group of marauders southeast, toward Egypt, and then settled in the southern Levant. With the dismantling of trade routes and the loss of copper trading ports such as Hala Sultan Tekke, the Bronze Age drew to a close. Ships like the one that wrecked off Ulu Burun disappeared for centuries. After the events of the twelfth century B.C., it became more difficult to obtain copper, as well as tin, from distant lands. However, people would soon develop a new metallurgic technology that was even stronger and more formidable than bronze. This new technology would quickly spread around the world and would soon usher in a new age, the age of iron.

Cyprus Under Assyrian, Egyptian and Persian Controls (1200 and 500 B.C.)

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The most important development on Cyprus between about 1200 and 1050 B.C. was the arrival of successive waves of immigrants from the Greek mainland. These newcomers brought with them, and perpetuated, Mycenaean customs of burial, dress, pottery, production, and warfare. At this time, Achaean immigrants introduced Greek to Cyprus. An Achaean society, politically dominant by the eleventh century B.C., most likely created the independent kingdoms ruled by wanaktes, or kings, on the island. The Greeks progressively gained control of major communities, such as Salamis, Kition, Lapithos, Palaeopaphos, and Soli. In the mid-eleventh century B.C., the Phoenicians occupied Kition on the southern coast of Cyprus. Their interest in Cyprus derived mainly from the island's rich copper mines and its forests, which provided an abundant source of timber for shipbuilding. At the end of the ninth century B.C., the Phoenicians established a cult for their goddess Astarte in a monumental temple at Kition. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

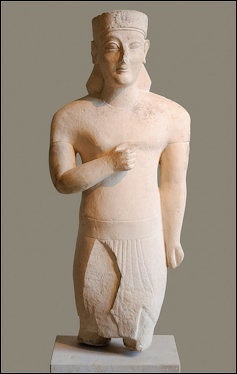

Cypriot statue

“A stele found at Kition reports the submission of the Cypriot kings to Assyria in 709 B.C. Under Assyrian domination, the kingdoms of Cyprus flourished and Cypriot kings enjoyed some independence as long as they regularly paid tribute to the Assyrian king. A seventh-century B.C. inscription records that there were ten kings of Cyprus who ruled over ten separate kingdoms. Some of these kings had Greek names, others had names of Semitic origin, testifying to the ethnic diversity of Cyprus in the first half of the first millennium B.C. Royal tombs at Salamis suggest both the wealth and foreign connections of these rulers in the eighth and seventh centuries B.C. \^/

“In the sixth century B.C., Egypt, under King Ahmose II, took control of Cyprus. Although the Cypriot kingdoms continued to manage relative independence, a significant increase of Egyptian motifs in Cypriot works of art from this period reflects the intensification of Egyptian influence. Elements such as the head of Hathor appeared in quantity for the first time, especially at Amathus. \^/

“In 545 B.C., under Cyrus the Great (r. ca. 559–530 B.C.), the Persian empire conquered Cyprus. The new rulers, however, did not interfere with established Cypriot institutions and religious practices. Cypriot troops participated in Persian military campaigns, the independent kingdoms paid the customary tribute, and Salamis ranked as the foremost kingdom. By the late sixth century B.C., Persian control over Cyprus tightened, so that by the beginning of the fifth century B.C. the island was an integral part of the Persian empire.” \^/

Classical Cyprus (ca. 480–310 B.C.)

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Throughout the Classical period, Cyprus was under the control of the Persian empire, which occupied the island sometime around 525 B.C. It was part of the Persian empire's "Fifth Satrapy," linking it with Phoenicia and Syria. Like the Phoenicians, the Cypriots were recognized as expert sailors and thus contributed men and ships in the Persian war against Greece in 480–479 B.C. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, July 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

“As allies of the Persian kings, the Phoenicians had considerable economic and political influence on Cyprus. During the fifth century B.C., three of the island's kingdoms—Salamis, Kition, and Lipithos—had Phoenician kings, Amathus was a Phoenician stronghold, and Idalion and Tamassos were under the Phoenician ruler of Kition. \^/

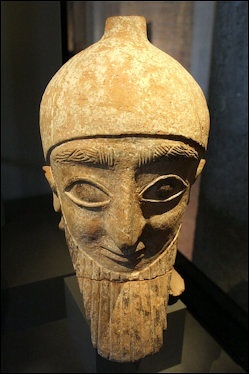

“The Phoenicians introduced their own gods and goddesses to Cyprus. Many of these deities correspond to Greek gods. For example, the Phoenician god Melqart closely resembles Herakles, and the war goddess Anat bears striking similarities to Athena. The Phoenician goddess of fertility and sexuality Astarte was eventually assimilated with Aphrodite, the Great Goddess of Cyprus. According to tradition, Cyprus was the birthplace of Aphrodite; the goddess was worshipped in monumental temples at Kition, Paphos, Amathus, and Golgoi, as well as in rural sanctuaries. But, unlike their Greek counterparts, Cypriot statues of Aphrodite depict the goddess fully clothed, and she typically wears a crown decorated with nude female figures that most likely represent the Eastern goddess Astarte. \^/

“Because of its political and economic ties with the Persian empire, Cyprus was for a long time cut off from the mainstream of Greek culture and trade. It was only from the late fifth century B.C., under the patronage of the philhellenic king Euagoras I of Salamis (r. ca. 411–ca. 373 B.C.), that friendly relations with Greece, particularly Athens, were restored. During his reign, Greek artists and intellectuals were welcomed in Cyprus, although there was always more incentive for Cypriot sculptors, philosophers, and writers to move from Cyprus to the Greek mainland. \^/

“For two centuries, until Alexander the Great liberated Cyprus in 333 B.C., the Cypriots fought for their independence. The Greeks joined them in their efforts to oust the Persians, and their presence on the island had stylistic implications for Cypriot art, particularly sculpture, which reflects a mixture of native and foreign influences. \^/

Hellenistic and Roman Cyprus

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Although Cyprus was liberated from the Persians by Alexander the Great in 333 B.C., the island did not enjoy a long period of freedom. After the death of Alexander in 323 B.C., his successors, the Diadochoi, quarreled and Cypriot rulers became entangled in antagonisms with tragic consequences—for example, the annihilation of the royal family of Salamis in 311 B.C. The wealth of its natural resources and its strategic position on the principal maritime route linking Greece and the Aegean with the Levant and Egypt made Cyprus a major prize for the warring Hellenistic rulers. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Eventually, in 300 B.C., the whole of Cyprus came under the control of the Ptolemies, who introduced the political and cultural institutions of the Hellenistic world to the island. The Ptolemies ruled Cyprus from Alexandria through high officials who resided in Paphos, which was easily accessible by sea from Alexandria. They abolished the independent kingdoms of Cyprus and established a unified rule and a single currency. Although the Cypriot syllabic script continued to be used and the native "Eteocypriot" tongue survived, largely as a spoken language, Greek became the dominant language. \^/

“At the beginning of the Hellenistic period, Attic influence was still evident in Cypriot art and funerary architecture, but Egyptian elements gradually prevailed. By the end of Ptolemaic rule, in 58 B.C., when the Romans annexed the island, local cults assimilated with Egyptian gods and goddesses, most notably Isis and Serapis. Cyprus continued in its age-old role as an intermediary between the Greek world and the Near East, with sculptors, craftsmen, and merchants from all over the eastern Mediterranean introducing diverse artistic styles and traditions. In ceramics, sculpture, and jewelry, the Cypriots followed the styles of the Hellenistic koine, inspired by the Alexandrian school. Stone sculpture continued to be produced, and portraiture, especially depictions of the royal family, became the main form of representation. \^/

“Roman involvement in Cypriot affairs began as early as 168 B.C., although Cyprus became a Roman province only in 58 B.C. During Roman rule, Paphos retained its position as the island's principal city and gained much fame from the temple of Aphrodite, which it advertised on its coinage. Amathus and Salamis were the two other major Roman centers, with temples to Aphrodite and Zeus respectively. Under the Romans, the island prospered and, apart from the time of the great Jewish revolt in 115/6 A.D., enjoyed the fruits of the Pax Romana. Numerous large-scale public buildings (temples, gymnasia, theaters, baths, and aqueducts) were erected, especially in the Antonine and Severan periods (mid-second to early third century A.D.). In arts and crafts, Cyprus became fully Romanized; in sculpture, ceramics, and glassmaking, one can see clearly that local producers followed styles common to the whole of the Roman world. Cyprus retained its position as an important link in the main maritime routes across the eastern Mediterranean, and its prosperity declined only when the Arabs disrupted these routes in the seventh century A.D.” \^/

Third-Century B.C., Football-Field-Size Tumulus Found in Cyprus

A large burial mound, known as the tumulus of Laona, found in Cyprus, is larger than a football field, which is 100 meters (328 feet) long and 60 meters (196 feet).Donavyn Coffey wrote in Live Science: It was likely built around the third century B.C., when the successors of Alexander the Great were fighting for control of Cyprus and large swaths of the empire. Researchers have been gradually excavating and digitally documenting the tumulus over the past decade. But in a new finding, archaeologists learned that the tumulus was erected on top of a broken rampart that is even older than the mound, dating to the early fifth century B.C. [Source: Donavyn Coffey, Live Science, August 25, 2022]

The tumulus is located one kilometer northeast of the Sanctuary of Aphrodite, an ancient site dating to the 12th century B.C. "The mound/tumulus was always visible, but the locals considered it a natural hillock," Giorgos Papantoniou, an assistant professor of ancient visual and material culture at Trinity College Dublin."Its geological identification as an artificial mound was confirmed in 2011."

In 2021, the team published a study in the journal Geoarchaeology, describing the tumulus as "an accomplished architectural structure" that was built over time in several stages. "As the height of the structure gradually increased, the tumulus became an imposing physical mark that gave the landscape a new meaning," the researchers wrote in the study.

The enormous burial mound's construction would have required a huge and experienced workforce led by expert engineers, the researchers said. However, it's unclear who built the monument. "The tumulus was constructed with local soils and sediments, but since there are no tumulus builders recorded from ancient Cyprus, the engineers with the required expertise must have been non-Cypriots, maybe Macedonians," Papantoniou said.

Fortress Discovered Under the Football-Field-Size Tumulus

Archaeologists excavating the enormous tumulus described above uncovered an even older structure underneath it — a rampart, or part of a defensive wall, from an ancient fortress, according to a statement from the Department of Antiquities Cyprus.Donavyn Coffey wrote in Live Science: Ancient people on Cyprus buried the fortress wall under about 484,000 cubic feet (13,700 cubic meters) of loose soil with sand, silt or clay, known as marl, and red soil, which had been transported from elsewhere on Cyprus for the construction of the tumulus. The Laona fortress was, therefore, well preserved under the tumulus; its northeast corner survives to a height of 20 feet (6 m), making it one of the most significant monuments of the "Age of the Cypriot Kingdoms", according to the University of Cypres Department of Antiquities. [Source: Donavyn Coffey, Live Science, August 25, 2022]

With the "unexpected discovery" of the broken rampart under the "lasting mega-monument," it's apparent that "Laona combines two monuments that are so far unique in the archaeology of Cyprus," the Department of Antiquities Cyprus said. The newly discovered rampart is Cypro-Classical, and is credited to the royal dynasty that ruled Paphos through the end of the fourth century B.C. The archaeologists report that the wall is functionally similar to and fits the same timeline as the palace and workshop complexes on the citadel of Hadjiabdoulla, which are only 230 feet (70 meters) away from Laona.

During a recent excavation, the antiquities team exposed the rampart's east side and two ancient staircases. Further analysis revealed that the rampart turned north under the highest point of the mound. "Its wall follows a descending NW course, and it is in an excellent state of preservation," the team said in the Facebook statement. The rare defensive monument is five meters (16 feet) wide and made of mold-made mud bricks between two parallel walls of unworked stone. Currently, the wall is 160 meters (525 feet) long; its internal area is at least 1,740 square meters (18,729 square feet), the University of Cyprus reported. Investigations at the base of the wall suggest that ancient people leveled the ground to start the project. On top of this leveled ground is a thick layer of river pebbles, followed by a layer of red soil containing sherds, or broken pieces of pottery, according to the statement.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except last map Researchgate

Text Sources: Internet Metropolitan Museum of Art, Live Science, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024