Home | Category: Bronze Age Europe / Minoans and Mycenaeans

MYCENAEANS

gold funerary mask The Mycenaeans founded the first advanced Greek-speaking culture and were immortalized in Homer’s “ Iliad” . They absorbed Minoan culture but they were a warlike people like the Spartans. They thrived between 1650 and 1200 B.C., roughly a millennia before classical ancient Greece. The Mycenaeans made weapons and armor from bronze and used them to conquer other cultures. Their leaders were buried with masks of gold.

The people who became the Mycenaeans are believed to have entered the Greek mainland from the north around 2000 B.C.. After conquering the Minoans around 1400 B.C. they set up trading posts all over the Mediterranean and Aegean. Their culture was influenced greatly by the Minoans. It is believed they may have fought some battles with Egyptians and Hittites. The civilization collapsed soon after the Trojan War in 1200 B.C.

Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The very first organized Greek society belonged to the Mycenaeans, whose kingdoms exploded out of nowhere on the Greek mainland around 1600 B.C. Although they disappeared equally dramatically a few hundred years later, giving way to several centuries known as the Greek Dark Ages, before the rise of “classical” Greece, the Mycenaeans sowed the seeds of our common traditions, including art and architecture, language, philosophy and literature, even democracy and religion. “This was a crucial time in the development of what would become Western civilization,” Stocker says. [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2017]

The Mycenaeans are named after the civilization’s wealthiest and best-known city. Mycenae is said to have been the home of Agamemnon and Nestor, the leaders of the forces that fought against the Trojans in the Trojan wars, and had links with Odysseus and other heroes described in the epics of Homer. . Many details about the Mycenaeans are found in the “Iliad”, some of which have been backed up with archaeological evidence.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MYCENAEAN SITES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MYCENAEAN CULTURE AND LIFE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MYCENAEAN RELIGION: BEEHIVE TOMBS AND MAYBE HUMAN SACRIFICES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MYCENAEAN MILITARY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MYCENAEAN FOREIGN RELATIONS: TRADE, SHIPS, EGYPTIANS, MINOANS, TROJANS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ILIAD: PLOT, CHARACTERS, BATTLES, FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HISTORICAL TROY: ARCHAEOLOGY, SITES, TROJAN WARS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MYCENAEAN ARCHAEOLOGY: GOLDEN MASKS AND THE GRIFFIN WARRIOR europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HEINRICH SCHLIEMANN, THE DISCOVER OF TROY AND MYCENAE europe.factsanddetails.com

Good Archaeology Websites Aegean Prehistoric Archaeology sites.dartmouth.edu; Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Livescience livescience.com/ ; Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Mycenaeans” by Rodney Castleden (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Mycenaeans” by Louise Schofield (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Mycenaeans C.1650–1100 BC” by Nicolas Grguric (2005) Amazon.com;

“Mycenaean Greece and the Aegean World: Palace and Province in the Late Bronze Age” by Margaretha Theodora Kramer-Hajós (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Mycenaeans” by William Taylour (1964) Amazon.com;

“The Mycenaean World” by John Chadwick (1976) Amazon.com;

“The Decipherment of Linear B” by John Chadwick (1958) Amazon.com;

“The Last Mycenaeans and Their Successors: An Archaeological Survey, C. 1200-c. 1000 B.C.” by Vincent Desborough (1964) Amazom.com

“The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age Illustrated Edition

by Cynthia W. Shelmerdine Amazon.com;

The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean” (Oxford Handbooks) by Eric H. Cline Amazon.com;

“The Aegean Bronze Age” by Oliver Dickinson (Cambridge World Archaeology) (1994) Amazon.com;

“Greece in the Bronze Age” by Emily Vermeule (1964) Amazon.com;

“The End of the Bronze Age” by Robert Drews (1995) Amazon.com;

History of the Myceneans

Throne in the so-called Palace of Nestor in Pylos

Around 2000 B.C. Greek-speaking immigrants moved into the Aegean. Skeletal remains confirm they were tall and well built. The newcomers looked first to the sea for food and later found that the dry and rocky soil was well suited for growing olives and grapes. It seems these people were a war-like lot, ruled by military leaders. In many ways they resembled the Vikings that would plague Europe some 25 centuries later- pirates, raiders and traders- who after a time settled down and became civilized. The term Mycenaean has been given to this civilization, derived from Mycenae, the site first excavated by Heinrich Schliemann after his discovery of fabled Troy. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

“The Mycenaeans began to trade and have cultural contact with the Minoans. The latter influenced the development of their cities, the production of trade goods and improvements in agriculture. Unlike Minoan cities, which had no or minimal fortifications, the Mycenaean settlements were heavily fortified with colossal perimeter walls. Since they periodically raided and looted towns in Hittite and Egyptian territory the massive fortifications were likely seen as a cost of “doing business”. The art themes depicted on Mycenaean artifacts (scenes of warfare and hunting) make a sharp contrast with the pastoral content of Minoan artwork. Their militaristic approach worked well for the Mycenaeans bringing power and prosperity. Between 1600 and 1200 B.C. their culture flourished.” |

Mycenae collapsed in 1200 B.C., perhaps as result of social unrest brought about after a series of earthquakes or famine, war or trade collapse. When the Hittite empire collapsed many great cities in Asia Minor were sacked. This have disrupted Mycenaean trade routes. Some scholars believe Mycenae was highly centralized and became overextended and collapsed under its own weight. There is no evidence of a foreign invasion or raid by tribes from the north. From the ashes of Mycenaean civilization, classical Greek culture arose several centuries later.

Mycenaean Civilization

Linear B writing

According to UNESCO: “Mycenaean civilization was renowned for its technical and artistic achievements but also its spiritual wealth, which spread around the Mediterranean world between 1600 and 1100 B.C. and played a vital role in the development of classical Greek culture. The palatial administrative system, the monumental architecture, the impressive artefacts and the first testimonies of Greek language, preserved on Linear B tablets, are unique elements of the Mycenaean culture.” [Source: UNESCO]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Mycenaean is the term applied to the art and culture of Greece from ca. 1600 to 1100 B.C. The name derives from the site of Mycenae in the Peloponnese, where once stood a great Mycenaean fortified palace. Mycenae is celebrated by Homer as the seat of King Agamemnon, who led the Greeks in the Trojan War. In modern archaeology, the site first gained renown through Heinrich Schliemann's excavations in the mid-1870s, which brought to light objects whose opulence and antiquity seemed to correspond to Homer's description of Agamemnon's palace. The extraordinary material wealth deposited in the Shaft Graves at Mycenae (ca. 1550 B.C.) attests to a powerful elite society that flourished in the subsequent four centuries. [Source: Colette Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Wide-ranging commerce circulated Mycenaean goods throughout the Mediterranean world from Spain and the Levant. The evidence consists primarily of vases, but their contents (oil, wine, and other commodities) were probably the chief objects of trade. Besides being bold traders, the Mycenaeans were fierce warriors and great engineers who designed and built remarkable bridges, fortification walls, and beehive-shaped tombs—all employing Cyclopean masonry—and elaborate drainage and irrigation systems. Their palatial centers, "Mycenae rich in gold" and "sandy Pylos," are immortalized in Homer's Iliad and Odyssey. Palace scribes employed a new script, Linear B, to record an early Greek language. In the Mycenaean palace at Pylos—the best preserved of its kind—Linear B tablets suggest that the king stood at the head of a highly organized feudal system. By the late thirteenth century B.C., however, mainland Greece witnessed a wave of destruction and the decline of the Mycenaean sites, and the withdrawal to more remote refuge settlements. \^/

Indo-Europeans

The Mycenaeans were Indo-Europeans. Around a 3000 B.C., during the early Bronze Age, Indo-European people began migrating into Europe, Iran and India and mixed with local people who eventually adopted their language. In Greece, these people were divided into fledgling city states from which the Mycenaeans and later the Greeks evolved. These Indo European people are believed to have been relatives of the Aryans, who migrated or invaded India and Asia Minor. The Hittites, and later the Greeks, Romans, Celts and nearly all Europeans and North Americans descended from Indo-European people.

Indo-Europeans is the general name for the people speaking Indo-European languages. They are the linguistic descendants of the people of the Yamnaya culture (c.3600-2300 B.C. in Ukraine and southern Russia who settled in the area from Western Europe to India in various migrations in the third, second, and early first millenniums B.C.. They are the ancestors of Persians, pre-Homeric Greeks, Teutons and Celts. [Source: Livius.com]

Indo-European intrusions into Iran and Asia Minor (Anatolia, Turkey) began about 3000 B.C.. The Indo-European tribes originated in the great central Eurasian Plains and spread into the Danube River valley possibly as early as 4500 B.C., where they may have been the destroyers of the Vinca Culture. Iranian tribes entered the plateau which now bears their name in the middle around 2500 B.C. and reached the Zagros Mountains which border Mesopotamia to the east by about 2250 B.C...

See Separate Article INDO-EUROPEANS factsanddetails.com

Mycenaeans Burst on the Scene Around 1600 B.C.

Andrew Curry wrote in Archaeology magazine: Nearly 150 years of archaeological excavations on the Greek mainland and Crete have shown that, beginning around 1600 B.C., the comparatively unsophisticated culture on the mainland underwent a radical transformation. “In time, there’s a blossoming of wealth and culture,” Stocker says. “Palaces are built, wealth accumulates, and power is consolidated in places such as Pylos and Mycenae.” The reasons for this leap forward are unknown. For a few centuries, the mainlanders imitated the Minoans. Pylos was an early Mycenaean power center, and buildings there at the time of the Griffin Warrior resembled the large houses with ashlar masonry found at Knossos on Crete. “There were probably four or five fancy mansions in Pylos at the time of the Griffin Warrior, all very Minoan in style,” Davis says. For example, the mansions had painted walls, a type of artistry pioneered by the Minoans. [Source: Andrew Curry, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2019]

In Pylos, Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “For several hundred years before Nestor’s palace was built, the region was dominated by the Minoans, whose sophisticated civilization arose on Crete, with skilled artisans and craftsmen who traded widely in the Aegean, Mediterranean and beyond. By contrast, the people of mainland Greece, a few hundred miles to the north across the Kythera Strait, lived simple lives in small settlements of mud-brick houses, quite unlike the impressive administrative centers and well-populated Cretan villages at Phaistos and Knossos, the latter home to a maze-like palace complex of over a thousand interlocking rooms. “With no sign of wealth, art or sophisticated architecture, mainland Greece must have been a pretty depressing place to live,” says Davis. “Then, everything changes.” [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2017]

“Around 1600 B.C., the mainlanders began leaving almost unimaginable treasures in tombs — “a sudden splash of brilliance,” in the words of Louise Schofield, the archaeologist and former British Museum curator, describing the jewelry, weapons and golden death masks discovered by Schliemann in the graves at Mycenae. The mainland population swelled; settlements grew in size, number and apparent wealth, with ruling elites becoming more cosmopolitan, exemplified by the diverse riches they buried with their dead. At Pylos, a huge, beehive-shaped stone tomb known as a tholos was constructed, connected to mansion houses on the hilltop by a ceremonial road that led through a gateway in a surrounding fortification wall. Although thieves looted the tholos long before it was rediscovered in modern times, from what was left behind — seal stones, miniature gold owls, amethyst beads — it appears to have been stuffed with valuables to rival those at Mycenae.

“This era, extending until the construction of palaces at Pylos, Mycenae and elsewhere, is known to scholars as the “shaft grave period” (after the graves that Schliemann discovered). Cynthia Shelmerdine, a classicist and renowned scholar of Mycenaean society at the University of Texas at Austin, describes this period as “the moment the door opens.” It is, she says, “the start of elites coming together to form something beyond just a minor chiefdom, the very beginning of what leads to the palatial civilization only a hundred years later.” From this first awakening, “it really takes a very short time for them to leap into full statehood and become great kings on a par with the Hittite emperor. It was a remarkable thing to happen.”

“Yet partly as a result of the building of the palaces themselves, atop the razed mansions of early Mycenaeans, very little is known of the people and culture that gave birth to them. You can’t just tear up the plaster floors to see what’s underneath, Davis explains. The tholos itself went out of use around the time the palace was built. Whoever the first leaders here were, Davis and Stocker had assumed, they were buried in this plundered tomb. Until, less than a hundred yards from the tholos, the researchers found the warrior grave.

Minoans and Mycenaeans

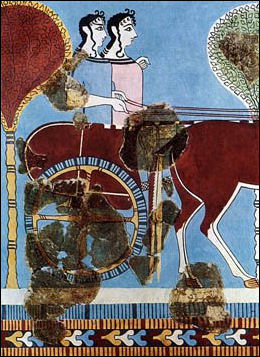

Mycenaean chariot The Minoans were a model for Mycenae and then a competitor and then were eclipsed by the Mycenaeans. The two cultures lived side by side until the 15th century B.C. when Minoa became a Mycenaean colony. First it was thought that maybe Minoans and Mycenaeans were the same people and that Mycenae was a colony of Knossos. Their art, written language and religion were that similar.

Andrew Curry wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Scholars have long debated the nature of the relationship between the Mycenaeans and the Minoans. This discussion has centered on whether Mycenaean culture, and what is thought of as ancient Greek culture, dating to half a millennium later, was imported from Crete, or was a homegrown phenomenon. But the exceptional discovery of the Griffin Warrior in 2015 — a man’s grave filled with more than 2,000 artifacts just outside Nestor’s palace in Pylos — suggests that the concept of competing cultures might obscure a deep interconnectedness. “Archaeologists have a way of cutting the world up into well-bounded cultural entities, but it seems that in the Late Bronze Age new identities were being formed,” says archaeologist Dimitri Nakassis of the University of Colorado Boulder. “There used to be clear lines between the Minoans and the Mycenaeans, but a lot of work now points out that these are our categories, not theirs.” [Source: Andrew Curry, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2019]

“The extraordinary contents of this man’s grave may be the key to understanding a far more complex development. Scholars are now beginning to believe that the shift from the Minoan to Mycenaean world may not have been a sharp transition achieved through colonization or conquest, but a more complicated process of cultural mixture and communication that only came to an end when mainland Mycenaean culture took over Crete around 1400 B.C. Says Jan Driessen, a Minoan specialist at the Catholic University of Louvain, “There’s no way to overestimate the tomb’s importance.”

Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: ““The fruits of that intermingling may have shaped the culture of classical Greece and beyond. In Greek mythology, for example, the legendary birthplace of Zeus is said to be a cave in the Dicte mountains on Crete, which may derive from a story about a local deity worshiped at Knossos. And several scholars have argued that the very notion of a Mycenaean king, known as a wanax, was inherited from Crete. Whereas the Near East featured autocratic kings — the Egyptian pharaoh, for example, whose supposed divine nature set him apart from earthly citizens — the wanax, says Davis, was the “highest-ranking member of a ranked society,” and different regions were served by different leaders. It’s possible, Davis proposes, that the transfer to Greek culture of this more diffuse, egalitarian model of authority was of fundamental importance for the development of representative government in Athens a thousand years later. “Way back in the Bronze Age,” he says, “maybe we’re already seeing the seeds of a system which ultimately allows for the emergence of democracies.”[Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2017]

Shift from Minoans to Mycenaeans

Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “Within a few years of the warrior’s burial, the tholos went out of use, the gateway in the fortification wall closed, and every building on the hilltop was destroyed to make way for the new palace. On Crete, Minoan palaces across the island burned along with many villas and towns, although precisely why they did remains unknown. Only the main center of Knossos was restored for posterity, but with its art, architecture and even tombs adopting a more mainland style. Its scribes switched from Linear A to Linear B, using the alphabet to write not the language of the Minoans, but Mycenaean Greek. It’s a crucial transition that archaeologists are desperate to understand, says Brogan. “What brings about the collapse of the Minoans, and at the same time what causes the emergence of the Mycenaean palace civilization?” [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2017]

“The distinctions between the two societies are clear enough, quite apart from the fundamental difference in their languages. The Mycenaeans organized their towns with free-standing houses rather than the conglomerated shared buildings seen on Crete, for example. But the relationship between the peoples has long been a contentious subject. In 1900, just 24 years after Schliemann announced he’d found Homer’s heroes at Mycenae, the British archaeologist Arthur Evans discovered the Minoan civilization (named for Crete’s mythic King Minos) when he unearthed Knossos. Evans and subsequent scholars argued that the Minoans, and not the Mycenaean mainlanders, were the “first” Greeks — “the first link in the European chain,” according to the historian Will Durant. Schliemann’s graves, the thinking went, belonged to wealthy rulers of Minoan colonies established on the mainland.

“In 1950, however, scholars finally deciphered Linear B tablets from Knossos and Pylos and showed the writing to be the earliest known form of Greek. Opinion now swung the other way: The Mycenaeans were reinstated as the first Greeks, and Minoan objects found in mainland graves were reinterpreted as status symbols stolen or imported from the island. “It’s like the Romans copying Greek statues and carting them off from Greece to put in their villas,” says Shelmerdine. And this has been the scholarly consensus ever since: The Mycenaeans, now thought to have sacked Knossos at around the time they built their mainland palaces and established their language and administrative system on Crete, were the true ancestors of Europe.

Mycenaean States (Wanax)

Most scholars today, believe there was no single ruler of the Mycenaean world-or even a unified Mycenaean realm over which one ruler ruled. The available evidence suggests that Bronze Age Greece was divided into several different political centers, each with its own ruler, or wanax. The wanax of Mycenae could have been one of the most powerful of these rulers, but his authority likely did not extend across the whole of Greece. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2023]

Around 1450 B.C., Greece was divided into a series of kingdoms on the Greek mainland, the most important centered at Mycenae, Tiryns, Pylos and Thebes. In the subsequent decades, the Mycenaeans began to expand throughout the Aegean, filling the niche previously filled by Neopalatial Minoan society. [Source Wikipedia]

The state of Mycenae was ruled by a king. Other states such as Pylos had their leaders. Under the king of Mycenae was a “leader of the people,” perhaps a military leader. There were landowners, nobles, tenant farmers, servants, slaves and people that engaged in a large number of trades and professions.

Thucydides: “On The Early History of the Hellenees”

Thucydides wrote in “On The Early History of the Hellenes (c. 395 B.C.): “The country which is now called Hellas was not regularly settled in ancient times. The people were migratory, and readily left their homes whenever they were overpowered by numbers. There was no commerce, and they could not safely hold intercourse with one another either by land or sea. The several tribes cultivated their own soil just enough to obtain a maintenance from it. But they had no accumulation of wealth, and did not plant the ground; for, being without walls, they were never sure that an invaded might not come and despoil them. Living in this manner and knowing that they could anywhere obtain a bare subsistence, they were always ready to migrate; so that they had neither great cities nor any considerable resources. The richest districts were most constantly changing their inhabitants; for example, the countries which are now called Thessaly and Boeotia, the greater part of the Peloponnesus with the exception of Arcadia, and all the best parts of Hellas. For the productiveness of the land increased the power of individuals; this in turn was a source of quarrels by which communities were ruined, while at the same time they were more exposed to attacks from without. Certainly Attica, of which the soil was poor and thin, enjoyed a long freedom from civil strife, and therefore retained its original inhabitants [the Pelasgians]. [Source: Thucydides, “The History of the Peloponnesian War,” translated by Benjamin Jowett, New York, Duttons, 1884, pp. 11-23, Sections 1.2-17, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

sacrifice of Nestor from the Pylos museum

“The feebleness of antiquity is further proved to me by the circumstance that there appears to have been no common action in Hellas before the Trojan War. And I am inclined to think that the very name was not as yet given to the whole country, and in fact did not exist at all before the time of Hellen, the son of Deucalion; the different tribes, of which the Pelasgian was the most widely spread, gave their own names to different districts. But when Hellen and his sons became powerful in Phthiotis, their aid was invoked by other cities, and those who associated with them gradually began to be called Hellenes, though a long time elapsed before the name was prevalent over the whole country. Of this, Homer affords the best evidence; for he, although he lived long after the Trojan War, nowhere uses this name collectively, but confines it to the followers of Achilles from Phthiotis, who were the original Hellenes; when speaking of the entire host, he calls them Danäans, or Argives, or Achaeans.

“And the first person known to us by tradition as having established a navy is Minos. He made himself master of what is now called the Aegean sea, and ruled over the Cyclades, into most of which he sent the first colonies, expelling the Carians and appointing his own sons governors; and thus did his best to put down piracy in those waters, a necessary step to secure the revenues for his own use. For in early times the Hellenes and the barbarians of the coast and islands, as communication by sea became more common, were tempted to turn pirates, under the conduct of their most powerful men; the motives being to serve their own cupidity and to support the needy. They would fall upon the unwalled and straggling towns, or rather villages, which they plundered, and maintained themselves by the plunder of them; for, as yet, such an occupation was held to be honoralbe and not disgraceful. . . .The land, too, was infested by robbers; and there are parts of Hellas in which the old practices continue, as for example among the Ozolian Locrians, Aetolians, Acarnanians, and the adjacent regions of the continent. The fashion of wearing arms among these continental tribes is a relic of their old predatory habits.

“For in ancient times all Hellenes carried weapons because their homes were undefended and intercourse was unsafe; like the barbarians they went armed in their everyday life. . . The Athenians were the first who laid aside arms and adopted an easier and more luxurious way of life. Quite recently the old-fashioned refinement of dress still lingered among the elder men of their richer class, who wore undergarments of linen, and bound back their hair in a knot with golden clasps in the form of grasshoppers; and the same customs long survived among the elders of Ionia, having been derived from their Athenian ancestors. On the other hand, the simple dress which is now common was first worn at Sparta; and there, more than anywhere else, the life of the rich was assimilated to that of the people.

“With respect to their towns, later on, at an era of increased facilities of navigation and a greater supply of capital, we find the shores becoming the site of walled towns, and the isthmuses being occupied for the purposes of commerce and defense against a neighbor. But the old towns, on account of the great prevalence of piracy, were built away from the sea, whether on the islands or the continent, and still remain in their old sites. But as soon as Minos had formed his navy, communication by sea became easier, as he colonized most of the islands, and thus expelled the malefactors. The coast population now began to apply themselves more closely to the acquisition of wealth, and their life became more settled; some even began to build themselves walls on the strength of their newly acquired riches. And it was at a somewhat later stage of this development that they went on the expedition against Troy.”

End of the Myceneans

Mycenae collapsed in 1200 B.C., perhaps as result of social unrest brought about after a series of earthquakes or famine, war or trade collapse. The disappearance of the Mycenaens is a Mediterranean mystery. Leading explanations include warfare with invaders or uprising by lower classes.

Mycenae collapsed around the same time the Hittite empire collapsed. When the Hittite empire collapsed many great cities in Asia Minor were sacked. This have disrupted Mycenaean trade routes. Some scholars believe Mycenae was highly centralized and became overextended and collapsed under its own weight. There is no evidence of a foreign invasion or raid by tribes from the north. From the ashes of Mycenaean civilization, classical Greek culture arose several centuries later.

So what happened to the Mycenaeans? The answer is that sometime around 1200 B.C. when the Mycenaean civilization was at its peak, it suddenly appears to have collapsed. Some scholars feel we will never know with certainty what happened and why. There are lots of theories: their history of military violence finally caught up with them; natural disaster in an area plagued with earthquakes and volcanic eruptions; the possibility of drought and famine followed by civil uprising. There is evidence of a lot of migration.” [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

Were the Mycenaeans Brought Down by an Earthquake

Some scientists think an earthquake, which strike Greece relatively frequently, could have contributed to the collapse of the Mycenaeans. At the ruins of Tiryns, a fortified palace, geologists are looking for clues of whether or not an earthquake did play a part in the was a likely culprit. Becky Oskin wrote in Live Science: Tiryns was one of the great Mycenaean cities. Atop a limestone hill, the city-state's king built a palace with walls so thick they were called Cyclopean, because only the one-eyed monster could have carried the massive limestone blocks. The walls were about 30 feet (10 meters) high and 26 feet (8 m) wide, with blocks weighing 13 tons, said Klaus-G. Hinzen, a seismologist at the University of Cologne in Germany and project leader. He presented his team's preliminary results April 19 at the Seismological Society of America's annual meeting in Salt Lake City. [Source: Becky Oskin, Live Science, April 23, 2013]

Hinzen and his colleagues have created a 3D model of Tiryns based on laser scans of the remaining structures. Their goal is to determine if the walls' collapse could only have been caused by an earthquake. Geophysical scanning of the sediment and rock layers beneath the surface will provide information for engineering studies on how the ground would shake in a temblor.

The work is complex, because many blocks were moved by amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann in 1884 and later 20th-century restorations, Hinzen said. By combing through historic photos, the team found unaltered wall sections to test. They also hope to use a technique called optical luminescence dating on soil under the blocks, which could reveal whether the walls toppled all at the same time, as during an earthquake. “This is really a challenge because of the alterations. We want to take a careful look at the original conditions," Hinzen told OurAmazingPlanet.

Another hurdle: finding the killer quake. There are no written records from the Mycenaean decline that describe a major earthquake, nor oral folklore. Hinzen also said compared with other areas of Greece, the region has relatively few active faults nearby. "There is no evidence for an earthquake at this time, but there was strong activity at the subduction zone nearby," he said.

The Mycenaean preference to place their fortresses atop limestone hills surrounded by sediment would concentrate shaking, even from distant earthquakes, Hinzen said. "The [seismic] waves get trapped in the outcrop and this can do a lot of damage. They are on very vulnerable sites," he said.

The researchers also plan to study the ancient Mycenaean city of Midea. The group has done similar work investigating ancient earthquakes in Turkey, Germany and Rome.

Late Bronze Age Collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse refers to widespread societal and state collapse during the 12th century B.C. associated with mass migration, and the destruction of cities and believed to have been caused of exacerbated by environmental change. The collapse affected a large area of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Near East, particularly Egypt, eastern Libya, the Balkans, the Aegean, Anatolia, and, to a lesser degree, the Caucasus. It was sudden, violent, and culturally disruptive for many Bronze Age civilizations, and it brought a sharp economic decline to regional powers, notably ushering in the Greek Dark Ages. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Late Bronze Age collapse triggered the collapse of Mycenaean Greek civilization and the Hittite Empire of Anatolia and the Levant. The Middle Assyrian Empire in Mesopotamia and the New Kingdom of Egypt survived but were weakened, Other cultures such as the Phoenicians enjoyed increased autonomy and power with the decline of Egyptian, Hittite and Assyria military presence in West Asia.In what is commonly known as the “Late Bronze Age collapse,” the Hittite Empire and the civilization of the Mycenaean Greeks, as well as many smaller powers and the trade networks that linked them, fell apart. It also led to anarchy, uprisings, civil wars, and rival pharaohs in Egypt, while Assyria and Babylonia suffered famines, outbreaks of disease, and foreign invasions.

Tom Metcalfe wrote in National Geographic: Scholars have struggled for 200 years to explain the collapse as a consequence of volcanic eruptions or earthquakes; piracy, migrations, or invasions; political or economic failures; diseases, famines, or climate change; or even of the spread of iron metallurgy throughout a region dominated by bronze. The historian Eric Clein said in his book "1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed" (2014), the reasons for the collapse aren't understood, but they may include a wars, social upheaval, invasions or famines caused by climate changes or triggered by natural disasters. The theories with the most support argue that the shift to a drier and colder climate in the eastern Mediterranean disrupted food production, leading to shortages that exacerbated the cultural and economic problems already occurring in the region.

See Separate Article: LATE BRONZE AGE COLLAPSE africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024