Home | Category: Education, Health and Transportation / Education, Health, Infrastructure and Transportation

HEALING TEMPLES IN THE GRECO-ROMAN WORLD

Asclepius

In the ancient Greek and Roman worlds, ailing people made pilgrimages to special sanctuaries called asklepieia dedicated to the physician-demigod Asklepios (or Asclepius), in the hopes of finding treatment for what ailed them. The first asklepieion appeared in ancient Greece as early as 500 B.C. Over the next several centuries, hundreds of them began operating throughout ancient Greece and the Italian peninsula.[Source Becky Little, National Geographic History, August 13, 2024]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Two of the most famous healing sanctuaries sacred to the god were at Epidauros and on the island of Kos. The success of the cult of Asklepios in antiquity was due to his accessibility—although the son of Apollo, he was still human enough to attempt to cancel death. Those who sought a cure in the temples erected to him were subjected to ritual purifications, fasts, prayers, and sacrifices. A central feature of the cult and the process of healing was known as incubation, during which the god appeared to the afflicted one in a dream and prescribed a treatment. [Source: Colette Hemingway, Independent Scholar,Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

Strabo wrote in “Geographia” (c. A.D. 20): “On the road between the Tralleians and Nysa is a village of the Nysaians, not far from the city Acharaca, where is the Plutonium, with a costly sacred precinct and a shrine of Pluto and Kore, and also the Charonium, a cave that lies above the sacred precinct, by nature wonderful; for they say that those who are diseased and give heed to the cures prescribed by these gods resort there and live in the village near the cave among experienced priests, who on their behalf sleep in the cave and through dreams prescribe the cures. These are also the men who invoke the healing power of the gods. And they often bring the sick into the cave and leave them there, to remain in quiet, like animals in their lurking-holes, without food for many days. And sometimes the sick give heed also to their own dreams, but still they use those other men, as priests, to initiate them into the mysteries and to counsel them. To all others the place is forbidden and deadly. [Source: Strabo, The Geography of Strabo: Literally Translated, with Notes, translated by H. C. Hamilton, & W. Falconer, (London: H. G. Bohn, 1854-1857)

RELATED ARTICLES:

HEALTH IN ANCIENT ROME: LONGEVITY, IDEAS, ISSUES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

DISEASES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HEALTH CARE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT ROMAN MEDICINES europe.factsanddetails.com

HEALTH IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HEALTH CARE IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

DOCTORS AND HEALTH CARE PRACTITIONERS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Asclepius: The God of Medicine” by Gerald D. Hart (2000) Amazon.com;

“Cure and Cult in Ancient Corinth: A Guide to the Asklepieion” by Mabel Lang (1977) href="https://amzn.to/4ccWuMq"> Amazon.com;

“The Temples and Ritual of Asklepios at Epidauros and Athens” (Classic reprint) by Richard Caton Amazon.com;

“Illness and Health Care in the Ancient Near East: The Role of the Temple in Greece, Mesopotamia, and Israel” (Harvard Semitic Monographs) by Hector Avalos (1995) Amazon.com;

“Votive Body Parts in Greek and Roman Religion” by Jessica Hughes (2017) Amazon.com;

“Rethinking the Concept of ‘Healing Settlements’: Water, Cults, Constructions and Contexts in the Ancient World” by Maddalena Bassani, Marion Bolder-Boos, et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“Thermal Spas in the Roman Provinces: The Role of Mineral-Medicinal Waters Across the Empire” by Silvia Gonzalez Soutelo (2024) Amazon.com;

“Healing, Disease and Placebo in Graeco-Roman Asclepius Temples: A Neurocognitive Approach” by Olympia Panagiotidou (2022) Amazon.com;

“Hippocrates' Oath and Asclepius' Snake: The Birth of the Medical Profession” by T.A. Cavanaugh Amazon.com;

“The Invention of Medicine: From Homer to Hippocrates” by Robin Lane Fox (2020)

Amazon.com;

“Ancient Medicine” (Sciences of Antiquity) by Vivian Nutton (2012) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Science, Technology, and Medicine in Ancient Greece and Rome (Blackwell) by Georgia L. Irby (2016) Amazon.com;

“Diseases in the Ancient Greek World” by Prof Mirko D. D. Grmek Amazon.com;

“Hippocrates, Volume II: Prognostic. Regimen in Acute Diseases. The Sacred Disease. The Art. Breaths. Law. Decorum.. Dentition (Loeb Classical Library) Amazon.com;

“Hippocrates, Volume XI: Diseases of Women 1–2" (Loeb) Amazon.com;

“Disability in Antiquity” by Christian Laes Amazon.com;

“Prosthetics and Assistive Technology in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Jane Draycott (2022) Amazon.com;

Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus: Healing Cult Sanatorium

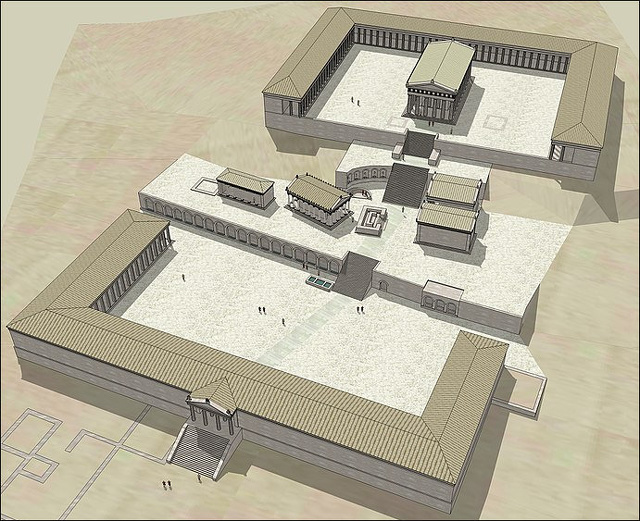

According to UNESCO: “In a small valley in the Peloponnesus, the shrine of Asklepios, the god of medicine, developed out of a much earlier cult of Apollo (Maleatas), during the 6th century B.C. at the latest, as the official cult of the city state of Epidaurus. Its principal monuments, particularly the temple of Asklepios, the Tholos and the Theatre - considered one of the purest masterpieces of Greek architecture – date from the 4th century. The vast site, with its temples and hospital buildings devoted to its healing gods, provides valuable insight into the healing cults of Greek and Roman times. [Source: UNESCO World Heritage Site website =]

“The Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus is a remarkable testament to the healing cults of the Ancient World and witness to the emergence of scientific medicine. Situated in the Peloponnese, in the Regional unit of Argolis, the site comprises a series of ancient monuments spread over two terraces and surrounded by a preserved natural landscape. Among the monuments of the Sanctuary is the striking Theatre of Epidaurus, which is renowned for its perfect architectural proportions and exemplary acoustics. The Theatre, together with the Temples of Artemis and Asklepios, the Tholos, the Enkoimeterion and the Propylaia, comprise a coherent assembly of monuments that illustrate the significance and power of the healing gods of the Hellenic and Roman worlds. =

“The Sanctuary is the earliest organized sanatorium and is significant for its association with the history of medicine, providing evidence of the transition from belief in divine healing to the science of medicine. Initially, in the 2nd millennium B.C. it was a site of ceremonial healing practices with curative associations that were later enriched through the cults of Apollo Maleatas in the 8th century B.C. and then by Asklepios in the 6th century B.C.. The Sanctuary of the two gods was developed into the single most important therapeutic center of the ancient world. These practices were subsequently spread to the rest of the Greco-Roman world and the Sanctuary thus became the cradle of medicine. =

“Among the facilities of the classical period are buildings that represent all the functions of the Sanctuary, including healing cults and rituals, library, baths, sports, accommodation, hospital and theatre. The Theatre of Epidaurus is an architectural masterpiece designed by the architect from Argos, Polykleitos the Younger, and represents a unique artistic achievement through its admirable integration into the site as well as the perfection of its proportions and acoustics. The Theatre has been revived thanks to an annual festival held there since 1955. =

Philostratos wrote in “Life of Apollonios of Tyana” (c. A.D. 190): “When the plague broke out at Ephesos and there was no stopping it, the Ephesians sent a delegation to Apollonios asking him to heal them. Accordingly, he did not hesitate, but said, "Let's go," and there he was, miraculously, in Ephesos. Calling together the people of Ephesos, he said, "Be brave; today I will stop the plague." Then he led them all to the theater where the statue of the God-Who-Averts-Evil had been set up. In the theater there was what seemed to be an old man begging, his eyes closed, apparently blind. He had a bag and a piece of bread. His clothes were ragged and his appearance was squalid. Apollonios gathered the Ephesians around him and said, "Collect as many stones as you can and throw them at this enemy of the Gods."The Ephesians were amazed at what he said and appalled at the idea of killing a stranger so obviously pitiful, for he was beseeching them to have mercy on him. But Apollonios urged them on to attack him and not let him escape. When some of the Ephesians began to pitch stones at him, the beggar who had his eyes closed as if blind suddenly opened them and they were filled with fire. At that point the Ephesians realized he was a demon and proceeded to stone him so that their missiles became a great pile over him. After a little while Apollonios told them to remove the stones and to see the wild animal they had killed. When they uncovered the man they thought they had thrown their stones at, they found he had disappeared, and in his place was a hound who looked like a hunting dog but was as big as the largest lion. He lay there in front of them, crushed by the stones, foaming at the corners of his mouth as mad dogs do. [Source: Philostratus, the Athenian, The Lives of the Sophists, translated by Wilmer Cave Wright, (London: Wm. Heinemann, 1922)

Significance of the Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus

“The site is one of the most complete ancient Greek sanctuaries of Antiquity and is significant for its architectural brilliance and influence. The Sanctuary of Epidaurus (with the Theatre, the Temples of Artemis and Asklepios, the Tholos, the Enkoimeterion, the Propylaia, the Banqueting Hall, the baths as well as the sport and hospital facilities) is an eminent example of a Hellenic architectural ensemble of the 4th century B.C.. The form of its buildings has exerted great influence on the evolution of Hellenistic and Roman architecture. Tholos influenced the development of Greek and Roman architecture, particularly the Corinthian order, while the Enkoimeterion stoa and the Propylaia introduced forms that evolved further in Hellenistic architecture. In addition, the complicated hydraulic system of the Sanctuary is an excellent example of a large-scale water supply and sewerage system that illustrates the significant engineering knowledge of ancient societies. The exquisitely preserved Theatre continues to be used for ancient drama performances and familiarizes the audience with ancient Greek thought. =

“The Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus exerted an influence on all the Asklepieia in the Hellenic world, and later, on all the Roman sanctuaries of Esculape. The group of buildings comprising the Sanctuary of Epidaurus bears exceptional testimony to the healing cults of the Hellenic and Roman worlds. The temples and the hospital facilities dedicated to the healing gods constitute a coherent and complete ensemble. Excavations led by Cavvadias, Papadimitriou and other archaeologists have greatly contributed to our knowledge of this ensemble. = The Theatre, the Temples of Artemis and Asklepios, the Tholos, the Enkoimeterion and the Propylaia make the Sanctuary of Epidaurus an eminent example of a Hellenic architectural ensemble of the 4th century B.C.. =

“The emergence of modern medicine in a sanctuary originally reputed for the psychically-based miraculous healing of supposedly incurable patients is directly and tangibly illustrated by the functional evolution of the Sanctuary of Epidaurus and is strikingly described by the engraved inscriptions on the remarkable stelai preserved in the Museum...The facilities that have been discovered in the Sanctuary represent all its functions during the entire duration of its use up until Early Christian times. These include the acts of worship, the procedure of healing with a dream-like state of induced sleep known as enkoimesis through the preparation of the patients, the facilitating of healing with exercise and the conduct of official games.

Treatments at Asklepieia

Becky Little wrote in National Geographic History: Pilgrims sought treatment at asklepieia for a wide range of issues, including headaches, blindness, and pregnancy complications. The treatments they received blended spirituality and medicine—and might seem more than a little unorthodox today. One of the most famous asklepieion pilgrims is Aelius Aristides, a Greek orator from the second century A.D. When he became too ill to give speeches, Aristides traveled to the Asklepieion of Pergamon. “He talks about feeling that his teeth are going to fall out, that his intestines are going to come out,” says Alexia Petsalis-Diomidis, a lecturer in classics at the University of St. Andrews and author of Truly Beyond Wonders: Aelius Aristides and the Cult of Asklepios. “He often says he can’t breathe.” [Source Becky Little, National Geographic History, August 13, 2024]

Some of the events ancient sources describe taking place at asklepieia defy modern medical explanations. At the Asklepieion of Epidaurus (now a UNESCO World Heritage site), ancient inscriptions detail the cures people received there. These include an unusual story about a woman named Cleo, whom the inscription says had been pregnant for five years. After sleeping at the sanctuary, Cleo reportedly woke up and gave birth to a son who was able to walk and wash himself.

There are also inscriptions at Epidaurus about people who were blind or had some visual impairment. In their dreams, Asklepios poured drugs into their eyes; and when they woke, they could see. Other inscriptions report that snakes or dogs healed people at the sanctuary by licking the afflicted parts of their bodies. Why snakes, you might ask? The animal has long been associated with Asklepios, and ancient depictions of the god show him holding a staff with a snake curled around it.

Today, we might describe this kind of care as “holistic,” says Helena C. Maltezou, director of research, studies, and documentation at Greece’s National Public Health Organization, and coauthor of a paper about asklepieia as forerunners of medical tourism.

Dream Cures at Healing Greco-Roman Temples

A central part of the treatment at asklepieia was sleeping site with the hope they would dream of Asklepios, whom pilgrims believed could cure them or at the very least advise them on how to treat their illnesses. With Aristides, it is hard to determine what he was suffering from, but we do know that he stayed at Pergamon for two years—an unusually long amount of time—and received multiple treatments, some based on interpretations of his dreams.

Becky Little wrote in National Geographic History: One of Aristides’ dreams at the sanctuary led him to receive an enema of honey. “He sees a statuette of the goddess Athena, goddess of wisdom,” Petsalis-Diomidis says. Athena was also the patron goddess of Athens in Attica, a region famous for its honey. To Aristides, the dream’s meaning was obvious: “it immediately occurred to me,” he wrote, “to have an enema of Attic honey.” (Of course!) [Source Becky Little, National Geographic History, August 13, 2024]

Aristides’ other dream-based treatments included exercising, bathing in cold water, and eating and avoiding certain foods. Pilgrims might also receive herbs or medicine, bathe in thermal springs, and participate in spiritually significant rituals. Aristides found it therapeutic to compose speeches during his stay at the asklepieion, even if he was too ill to deliver them.

To be fair to Aristides, recent studies have investigated whether honey enemas can treat acute pouchitis in humans and ulcerative colitis in rats (the human study never posted results, but the rat study found honey reduced colonic inflammation). However, there are many parts of the historical asklepieion experience that we can’t easily explain through a modern scientific lens.

Many other pilgrims reported dreams in which Asklepios performed surgery on them. There is some scholarly debate, however, as to whether surgery actually took place at asklepieia. Although archaeologists have discovered surgical tools at these sanctuaries, this may be because physicians dedicated their tools there, says Bronwen L. Wickkiser, ancient history professor at Hunter College, CUNY, and author of Asklepios, Medicine, and the Politics of Healing in

Miraculous Cures at Aesculapian Sanctuaries

remains of the Asclepeion Temple in Epidaurus

The healing methods of the priests of Aesculapius were especially distinguished from those of the professional physicians by the veil of secrecy and miracle which surrounded them, since they rightly understood that the love of wonders among the common people would always bring them success.

There is an account of the cure of a blind woman to whom Aesculapius appears in a dream, and restores her sight by dropping some healing lotion into her eyes, in return for the promise that she will dedicate a silver pig to Aesculapius (to whom pigs were often sacrificed), as a penalty for having come to the temple in a state of unbelief. Such cures of blindness are often mentioned in the inscriptions; sometimes the dog, which was also sacred to Aesculapius, takes the place of the god, as the snakes did in Aristophanes, and cures the eyes by licking them; in another case the snake of Aesculapius cures the wounded toes of a patient by licking.

Many cases are even more wonderful. A man, who has completely lost one of his eyes, receives the lost eye again by means of healing lotion poured into his sockets by the god during sleep. A woman, who has a worm in her body, dreams that Aesculapius cuts it open for her, takes the worm out, and sews it up again. A man has moles on his forehead, which the god removes by laying a bandage over his brow, whereupon next moment it appears perfectly white and pure, while the moles are left on the bandage; another man has lost the use of the fingers of one hand, the god jumps on his hand and pulls his fingers straight again, whereupon he is once more able to use them, etc., etc. Indeed, Aesculapius not only cures sick people, but also lifeless objects. A slave has broken his master’s cup, and as he sits sadly looking at it, a passer-by laughingly says that even Aesculapius could not mend that. That suggests to him taking the fragments into the temple, and next morning, when he opens the case in which he has put them, behold, the cup is whole again!

It is difficult to say which part of these stories is mere charlatanism and what refers to real medical treatment by means of operation. It is but natural that the priests at first got information by questioning each patient about his illness. The sleep in the sanctuary, which was indispensable for healing, was probably not a natural one, but either a mesmeric sleep — since undoubtedly the ancients were acquainted with this — or else a half-sleep induced by some narcotic, during which the priests in the service of Aesculapius or their assistants appeared and performed slight surgical operations on the sick people. This hypothesis is the more probable, since all the cures mentioned in these inscriptions from Epidaurus (which, though dating from the time of Alexander the Great, are copies of older inscriptions, probably of the fifth century) deal only with external means and never with internal treatment; no medicine or healing drink is mentioned.

Did the Sanctuary of Asklepios Have Ramps for the Disabled?

Many of the ancient visitors to the sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidaurus in the northeastern Peloponnese are described in inscriptions as walking with canes and crutches or being carried on litters or wagons. According to Archaeology magazine: By the fourth century B.C., the sanctuary had been equipped with at least 11 stone ramps that provided access to a number of its raised temples and other public spaces. Archaeologist Debby Sneed of California State University, Long Beach, has found that such ramps were installed much more frequently at sanctuaries associated with healing, and contends that the ramps were purposely built to serve these sanctuaries’ mobility-impaired visitors. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

In contrast to today’s disability accommodations, however, ancient Greek architects’ design choices were not motivated by progressive social reforms, but by the desire to ensure the continued success of healing sanctuaries. “It was a very practical decision for the Greeks to make sanctuaries accessible,” Sneed says. “Since their clientele was impaired, they needed infrastructure to enable these visitors to use all the spaces.”

Sarah Cascone wrote in Artnet: Studying a variety of temples, primarily from the 4th century AD, Sneed found that the buildings that had the most ramps were typically temples of healing — places that the elderly and mobility impaired would have difficulty climbing the steep stairs for entry. “Archaeologists have long known about ramps on ancient Greek temples, but have routinely ignored them in their discussions of Greek architecture,” said Sneed in a statement. “The likeliest reason why ancient Greek architects constructed ramps was to make sites accessible to mobility-impaired visitors.” [Source Sarah Cascone, Artnet.com,July 21, 2020]

Earlier theories posited that ramps were used to lead animal sacrifices into the temple, or for carting heavy building materials during construction. Sneed allows that ramps could have had multiple uses, but points to the prevalence of ramps at temples dedicated to Asclepius, the Greek god of healing, as evidence to support her hypothesis. “There’s this assumption that there is no room in Greek society for people who weren’t able-bodied,” Sneed told Science. But she argues that many ancient Greek skeletons show signs of arthritis, and painted figures on vases and sculptures often lean on canes or crutches. Even Hephaestus, one of the 12 Olympian gods, walked with a limp. And supplicants visiting ancient temples to Asclepius often left behind sculptures of legs and feet as an offering, in search of a cure for physical ailments on those parts of the body.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2024