Home | Category: Education, Health, Infrastructure and Transportation

ANCIENT ROMAN CURRICULUM

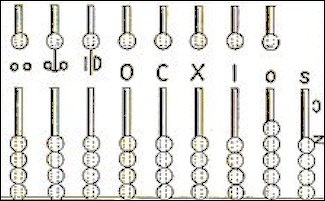

abacus

Boys of wealthy parents were tutored in mythology, Greek language, literature and rhetoric. Girls generally did not receive an education, and when they did it was by private tutors who came to their homes. At Greek gymnasiums students studied the "seven liberal arts" (arithmetic, music, geometry, astronomy, grammar, dialectic (logic) and rhetoric). Romans adopted a similar curriculum.

Oliver Thatcher wrote: “ ”The ordinary education of a boy was supposed to include music, gymnastics, and geometry. Under music was included Greek and Latin literature, under geometry what little was known in science. The subjects for education above what might be called the grammar school were oratory and the philosophers....The open highway through politics was oratory, and hence oratory was considered practically the only subject worthy to be the end of a youth's education.” [Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 370-391]

Seneca disapproved of teaching methods which do not prepare men for life, but only pupils for school: "non vitae sed scholae discimus" On the first page of his romance Petronius pokes fun at the sonority of pompous phrases which filled the classrooms of his day. Tacitus sadly remarks that "the tyrannicides, the plague cures, the incests of mothers which are so grandiloquently discussed in the schools bear no relation to the 'forum' and that all this bombast hurls defiance at the truth." [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

RELATED ARTICLES:

EDUCATION IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

SCHOOLS IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

TEACHERS IN ANCIENT ROME: TYPES, METHODS, PAY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HIGHER EDUCATION IN ANCIENT ROME — RHETORIC AND TRAVELING europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Science Education in the Early Roman Empire” by Richard Carrier PhD (2016) Amazon.com;

“Literate Education in the Hellenistic and Roman Worlds” by Teresa Morgan (2007)

Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Childhood and Education in the Classical World” by Judith Evans Grubbs and Tim Parkin (2013) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Education” by Robin Barrow (2011) Amazon.com;

“Roman Education From Cicero to Quintilian” (Classic Reprint) by Aubrey Gwynn (1892-1983) Amazon.com;

“A History Of Education In Antiquity” by H.I. Marrou and George Lamb (1982) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Education: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Mark Joyal , J.C Yardley, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“Gymnastics of the Mind: Greek Education in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt”

by Raffaella Cribiore (2005) Amazon.com;

“Libraries in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome: Daily Life, Mysteries, and Curiosities”

by Alberto Angela, Gregory Conti (2009) Amazon.com

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“24 Hours in Ancient Rome: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Philip Matyszak (2017) Amazon.com

“As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History” by Jo-Ann Shelton, Pauline Ripat (1988) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998)

Subjects Taught to Roman Elementary-School-Age Children

In the elementary schools the only subjects taught were reading, writing, and arithmetic. In the first, great stress was laid upon the pronunciation; the sounds were easy enough, but quantity was hard to master. The teacher pronounced first, syllable by syllable, then the separate words, and finally the whole sentence; the pupils pronounced after him at the tops of their voices. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

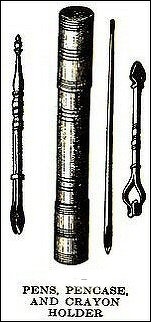

In the teaching of writing, wax tablets were employed, much as slates were a generation ago. The teacher first traced with a stilus the letters that served as a copy, then he guided the pupil’s hand with his own until the child learned to form the letters independently. When some dexterity had been acquired, the pupil was taught to use the reed pen and write with ink upon papyrus. For practice, the blank sides of sheets that had already been employed for more important purposes were used. If there were any books at all in these schools, the pupils must have made them for themselves by writing from the teacher’s dictation. |+|

“In arithmetic mental calculation was emphasized, but the pupil was taught to use his fingers in a very elaborate manner that is not now thoroughly understood. Harder sums were worked out with the help of the reckoning board (abacus). In addition to all this, much attention was paid to training the memory, and every pupil was made to learn by heart all sorts of wise and pithy sayings, especially the Twelve Tables of the Law. These last became a regular fetich in the schools, and, even when the language in which they were written had become obsolete, pupils continued to learn and recite them. Cicero learned them in his boyhood, but within his lifetime they were dropped from the schools.” |+|

Plutarch on What Should Be Taught

Plutarch wrote in “The Training of Children” (c. A.D. 110): “8. In brief therefore I say (and what I say may justly challenge the repute of an oracle rather than of advice), that the one chief thing in that matter — which comprises the beginning, middle and end of all — is good education and regular instruction; and that these two afford great help and assistance toward the attainment of virtue and felicity. For all other good things are but human and of small value, such as will hardly recompense the industry required to the getting of them. It is, indeed, a desirable thing to be well-descended; but the glory belongs to our ancestors. Riches are valuable; but they are the goods of Fortune, who frequently takes them from those that have them, and carries them to those that never so much as hoped for them. Yes, the greater they are, the fairer mark they are for those to aim at who design to make our bags their prize; I mean evil servants and accusers. But the weightiest consideration of all is, that riches may be enjoyed by the worst as well as the best of men. Glory is a thing deserving respect, but unstable; beauty is a prize that men fight to obtain, but, when obtained, it is of little continuance; health is a precious enjoyment, but easily impaired; strength is a thing desirable, but apt to be the prey of disease and old age. [Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 370-391]

“And, in general, let any man who values himself upon strength of body know that he makes a great mistake; for what indeed is any proportion of human strength, if compared to that of other animals, such as elephants and bulls and lions? But learning alone, of all things in our possession, is immortal and divine. And two things there are that are most peculiar to human nature, reason and speech; of which two, reason is the master of speech, and speech is the servant of reason, impregnable against all assaults of fortune, not to be taken away by false accusation, nor impaired by sickness, nor enfeebled by old age.

“For reason alone grows youthful by age; and time, which decays all other things before it carries them away with it, leaves learning alone behind. Whence the answer seems to me very remarkable, which Stilpo, a philosopher of Megara, gave to Demetrius, who, when he leveled that city to the ground and made the citizens slaves, asked Stilpo whether he had lost anything. Nothing, he said, for war cannot plunder virtue. To this saying that of Socrates also is very agreeable; who, when Gorgias (as I take it) asked him what his opinion was of the king of Persia, and whether he judged him happy, returned answer, that he could not tell what to think of him, because he knew not how he was furnished with virtue and learning — as judging human felicity to consist in those endowments, and not in those which are subject to fortune.”

“Wherefore, though we ought not to permit an ingenious child entirely to neglect any of the common sorts of learning, so far as they may be gotten by lectures or from public shows; yet I would have him to salute these only as in his passage, taking a bare taste of each of them (seeing no man can possibly attain to perfection in all), and to give philosophy the pre-eminence of them all. I can illustrate my meaning by an example. It is a fine thing to sail around and visit many cities, but it is profitable to fix our dwelling in the best. Witty also was the saying of Bias, the philosopher, that, as the wooers of Penelope, when they could not have their desire of the mistress, contented themselves to have to do with her maids, so commonly those students who are not capable of understanding philosophy waste themselves in the study of those sciences that are of no value. Whence it follows, that we ought to make philosophy the chief of all our learning. For though, in order to the welfare of the body, the industry of men has found out two arts — medicine, which assists to the recovery of lost health, and gymnastics, which help us to attain a sound constitution — yet there is but one remedy for the distempers and diseases of the mind, and that is philosophy. For by the advice and assistance thereof it is that we come to understand what is honest, and what dishonest; what is just, and what unjust; in a word, what we are to seek, and what to avoid.

“We learn by it how we are to demean ourselves towards the gods, towards our parents, our elders, the laws, strangers, governors, friends, wives, children, and servants. That is, we are to worship the gods, to honor our parents, to reverence our elders, to be subject to the laws, to obey our governors, to love our friends, to use sobriety towards our wives, to be affectionate to our children, and not to treat our servants insolently; and (which is the chief lesson of all) not to be overjoyed in prosperity nor too much dejected in adversity; not to be dissolute in our pleasures, nor in our anger to be transported with brutish rage and fury. These things I account the principal advantages which we gain by philosophy. For to use prosperity generously is the part of a man: to manage it so as to decline envy, of a well-governed man; to master our pleasures by reason is the property of wise men; and to moderate anger is the attainment only of extraordinary men. But those of all men I count most complete, who know how to mix and temper the management of civil affairs with philosophy; seeing they are thereby masters of two of the greatest good things that are — a life of public usefulness as statesmen, and a life of calm tranquility as students of philosophy. For, whereas there are three sorts of lives — the life of action, the life of contemplation, and the life of pleasure — the man who is utterly abandoned and a slave to pleasure is brutish and mean-spirited; he that spends his time in contemplation without action is an unprofitable man; and he that lives in action and is destitute of philosophy is a rustical man, and commits many absurdities. Wherefore we are to apply our utmost endeavor to enable ourselves for both; that is, to manage public employments, and withal, at convenient seasons, to give ourselves to philosophical studies. Such statesmen were Pericles and Archytas the Tarentine; such were Dion the Syracusan and Epaminondas the Theban, both of whom were of Plato's familiar acquaintance.

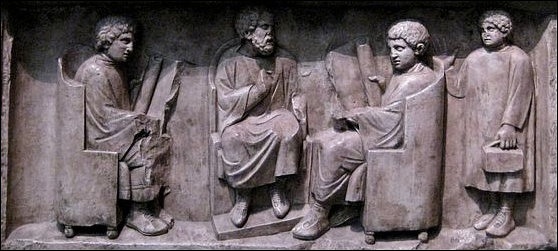

Roman school

Study of Greek in Ancient Rome

Between nine and twelve years of age, boys from affluent families studied with a with a grammaticus, who focused on his students' writing and speaking skills, versed them in the art of poetic analysis, and taught them Greek if they did not yet know it.

Early in the second century B.C. the Conscript Fathers, whose arms and diplomacy were now being turned against the Greeks, began to feel the necessity of not allowing their sons to be less cultivated than the subjects and vassals whom they were henceforth to govern. They therefore encouraged the foundation in Rome of schools of the Hellenistic type to rival those which flourished in the East, at Athens, at Pergamum, and at Rhodes, and they wished these schools to teach after the Greek manner everything known to the most learried Greeks. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

At the same time they were not unmindful of the political power which this superior education would confer; they had no wish to cede an inch of their political monopoly; they therefore contrived that these new educational advantages should be reserved for their own social caste. The first professors of grammar and rhetoric whom they permitted to set up in Rome were refugees from Asia and Egypt, victims of Aristonicus and of Ptolemy Physkon, to whom Rome offered sanctuary. All of them taught in Greek. When later these original teachers were superseded by Italians, the new grammatici and rhetoricians conformed to the Greek usage and borrowed the Greek language.

The grammar classes were conducted in Greek and Latin, but the rhetoric classes almost exclusively in Greek, and in this language all further education was continued. There were, of course, a few attempts to break through this convention which made for isolation. At the time of the democratic revolution with which the name of Marius is linked, one of his clients, the orator Plotius Gallus, had the hardihood to address his pupils in Latin; and a few years later the Rhetorica ad Herennium was published. Interlarded with examples taken from recent history and crammed with references to the subjects debated in the cotpitia, it was evidently inspired by the some tendency toward the liberal, the concrete, and the popular.

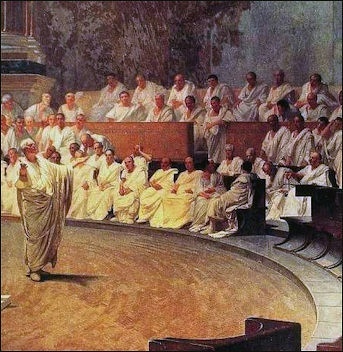

Rhetoric and Oratory

Rhetoric was the final stage in Roman education. Very few boys went on to study it. Early on in Roman history, it may have been the only way to train as a lawyer or politician. [Source Wikipedia]

Oliver Thatcher wrote: “ To understand the position of oratory and of an instructor in it at Athens or Rome the reader must consider how little there was to learn then as compared with today. The ordinary education of a boy was supposed to include music, gymnastics, and geometry. Under music was included Greek and Latin literature, under geometry what little was known in science. The subjects for education above what might be called the grammar school were oratory and the philosophers. A Roman's fields for action were politics and war. He learned to command in the field, and usually won the right to command through politics. The open highway through politics was oratory, and hence oratory was considered practically the only subject worthy to be the end of a youth's education.” [Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 370-391]

Quintilian wrote in “The Institutes,” Book 1: 1-26 (c. 90 A.D.): “We are giving small instructions, while professing to educate an orator; but even studies have their infancy; and as the rearing of the very strongest bodies commenced with milk and the cradle, so he, who was to be the most eloquent of men, once uttered cries, tried to speak at first with a stuttering voice, and hesitated at the shapes of the letters. Nor, if it is impossible to learn a thing completely, is it therefore unnecessary to learn it at all. [Source: Quintilian (b.30/35-A.D. c.100), The Ideal Education, “The Institutes,” Book 1: 1-26 (c. 90 A.D.), Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 370-391]

“If no one blames a father, who thinks that these matters are not to be neglected in regard to his son, why should he be blamed who communicates to the public what he would practice to advantage in his own house? And this is so much the more the case, as younger minds more easily take in small things; and as bodies cannot be formed to certain flexures of the limbs unless while they are tender, so even strength itself makes our minds likewise more unyielding to most things.”

Plutarch on the Importance of Being a Good Speaker

Plutarch wrote in “The Training of Children” (c. A.D. 110): “Still, before a person arrives at complete manhood, I would not permit him to speak upon any sudden incident occasion; though, after he has attained a radicated faculty of speaking, he may allow himself a greater liberty, as opportunity is offered. For as they who have been a long time in chains, when they are at last set at liberty, are unable to walk, on account of their former continual restraint, and are very apt to trip, so they who have been used to a fettered way of speaking a great while, if upon any occasion they be enforced to speak on a sudden, will hardly be able to express themselves without some tokens of their former confinement. But to permit those that are yet children to speak extemporally is to give them occasion for extremely idle talk. A wretched painter, they say, showing Apelles a picture, told him withal that he had taken a very little time to paint it. If you had not told me so, said Apelles, I see cause enough to believe it was a hasty draft; but I wonder that in that space of time you have not painted many more such pictures. [Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 370-391]

“I advise therefore (for I return now to the subject that I have digressed from) the shunning and avoiding, not merely of a starched, theatrical, and over-tragedial form of speaking, but also of that which is too low and mean. For that which is too swelling is not fit for the management of public affairs; and that, on the other side, which is too thin is very inapt to work any notable impression upon the hearers. For as it is not only requisite that a man's body be healthy, but also that it be of a firm constitution, so ought a discourse to be not only sound, but nervous also. For though such as is composed cautiously may be commended, yet that is all it can arrive at; whereas that which has some adventurous passages in it is admired also. And my opinion is the same concerning the affections of the speaker's mind. For he must be neither of a too confident nor of a too mean and dejected spirit; for the one is apt to lead to impudence, the other to servility; and much of the orator's art, as well as great circumspection, is required to direct his course skillfully betwixt the two.

“And now (whilst I am handling this point concerning the instruction of children) I will also give you my judgment concerning the frame of a discourse; which is this, that to compose it in all parts uniformly not only is a great argument of a defect in learning, but also is apt, I think, to nauseate the auditory when it is practiced; and in no case can it give lasting pleasure. For to sing the same tune, as the saying is, is in everything cloying and offensive; but men are generally pleased with variety, as in speeches and pageants, so in all other entertainments.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and "The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024