Home | Category: Food and Sex

WINE IN ANCIENT ROME

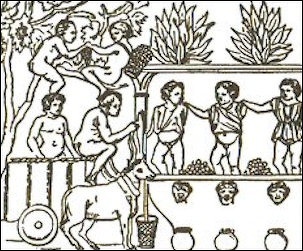

wine making

Wine was far and away the main alcoholic drink. It was consumed with meals and at parties, regarded as sources of good conversation and extolled in poems by some of Rome's greatest writers. Ovid wrote: “There, when the wine is set, you will tell me many a tale — how your ship was all but engulfed in the midst of the waters, and how, while hastening home to me, you feared neither hours of unfriendly night nor headlong winds of the south", adding it gave courage while “sorrow and worry take wing”

Grape juice became wine quickly because there was no refrigeration or preservatives in ancient times. Roman wine tended to be sweet and highly alcoholic because late season grapes were used. Romans followed the Greek custom and diluted their wine with water: the common belief was that only Barbarians would drink it straight. The water content depended on the setting. At family meals water to wine ratio was about 3:1. In taverns there was often little water. The wine was often safer to drink than the water. The acids and the alcoholic curbed the growth of bacteria and other pathogens.

To sweeten their wine, which could be vinegary, Romans added honey and water to it. Better grades went to the elite while cheaper, vinegary stuff went to slaves. Mario Indelicato, an archaeologist at the University of Catania in Sicily told The Guardian: “An edict was issued in the first century A.D. halting the planting of vineyards because people were not growing wheat any more,” said Indelicato. The Romans took the concept of getting together for a drink from the Greeks after they conquered the Greek-controlled Italian city of Taranto in the third century B.C. They drank at festivals to mark the pending harvest, after the harvest. In fact, any occasion was good for a drink.” [Source: Tom Kington, guardian.com, August 22, 2013]

Romans believed that wine was a medicine. Roman soldiers were required to drink a liter of wine a day. Families often had it with every meal. The rich took trouble to drink wine in especially beautiful places like gardens when certain flowers were in bloom. Taverns were filled large jug-like amphoras which were filed with wine.

See Separate Articles:

DRINKS AND DRINKING IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com

ORIGIN OF ALCOHOLIC DRINKS factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST WINES, WINEMAKING, WINERIES AND WINE GRAPES factsanddetails.com ;

WINE, DRINKING AND DRINKS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Vinum: The Story of Roman Wine” by Stuart Fleming (2001) Amazon.com;

“Food and Drink in Antiquity: A Sourcebook: Readings from the Graeco-Roman World” (Bloomsbury Sources in Ancient History) by John F. Donahue (2015) Amazon.com;

“Around the Roman Table: Food and Feasting in Ancient Rome” by Patrick Faas and Shaun Whiteside (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Satyricon” (Penguin Classics) by Petronius (Gaius Petronius Arbiter Amazon.com

“The Deipnosophists” (Banquet of the Learned) Vol. 1 by Naucratis Athenaeus, written about A.D. 200, Amazon.com;

“From Vines to Wines in Classical Rome” by David L. Thurmond (2016) Amazon.com;

“Dolia: The Containers That Made Rome an Empire of Wine”

by Caroline Cheung (2024) Amazon.com;

“Roman and Late Antique Wine Production in the Eastern Mediterranean: A Comparative Archaeological Study at Antiochia ad Cragum (Turkey) and Delos (Greece)” by Emlyn Dodd | (2020) Amazon.com;

“Wine in Ancient Greece and Cyprus: Production, Trade and Social Significance”

by Evi Margaritis, Jane M. Renfrew, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Amphoras and the Ancient Wine Trade” by Virginia R. Grace (1980) Amazon.com;

“Tracing the Origins of Wine in the Ancient Mediterranean” by Luke Gorton (2025) Amazon.com;

“Methods in Ancient Wine Archaeology: Scientific Approaches in Roman Contexts”

by Emlyn Dodd and Dimitri Van Limbergen (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture (Princeton Science Library)

by Patrick E. McGovern (2019) Amazon.com;

“Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages”

by Patrick E. McGovern (2009) Amazon.com;

“Wine Grapes: A Complete Guide to 1,368 Vine Varieties, Including Their Origins and Flavours” by Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding, et al. (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Origins and Ancient History of Wine: Food and Nutrition in History and Antropology” by Patrick E. McGovern, Stuart J. Fleming, et al. (2015) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Wine Drinking in Ancient Rome

Romans were famed for their love of wine. From what best can be determined everybody drank: from the rich in lavish villas to soldiers and sailors in provincial inns. For some wine-making was the life’s greatest pleasure. One tombstone in Tibur, just outside Rome, read: “Flavius Agricola [was] my name...Friends who read this listen to my advice: Mix wine, then place the garlands around you head, drink deep. And do not deny pretty girls the sweets of love.”

Romans were famed for their love of wine. From what best can be determined everybody drank: from the rich in lavish villas to soldiers and sailors in provincial inns. For some wine-making was the life’s greatest pleasure. One tombstone in Tibur, just outside Rome, read: “Flavius Agricola [was] my name...Friends who read this listen to my advice: Mix wine, then place the garlands around you head, drink deep. And do not deny pretty girls the sweets of love.”

By some estimates Rome's 1 million citizens and slaves drank an astonishing average of three liters of wine a day. Although most everyone drank wine diluted with water, people complained if they thought they were being shortchanged. One piece of graffiti found read, “May cheating like this trip you up bartender. You sell water and yourself drink undiluted wine.

Katharine Raff of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “At the Roman banquet, wine was served throughout the meal as an accompaniment to the food. This practice contrasted with that of the Greek deipnon, or main meal, which focused on the consumption of food; wine was reserved for the symposium that followed. Like the Greeks, the Romans mixed their wine with water prior to drinking. The mixing of hot water, which was heated using special boilers known as authepsae, seems to have been a specifically Roman custom. Such devices (similar to later samovars) are depicted in Roman paintings and mosaics, and some examples have been found in archaeological contexts in different parts of the Roman empire. Cold water and, more rarely, ice or snow were also used for mixing. Typically, the wine was mixed to the guest's taste and in his own cup, unlike the Greek practice of communal mixing for the entire party in a large krater (mixing bowl). Wine was poured into the drinking cup with a simpulum (ladle), which allowed the server to measure out a specific quantity of wine.” [Source: Katharine Raff, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2011, metmuseum.org \^/]

There were a number of ideas circulated around of how to improve the taste of wine. Pliny the Elder recommended adding “seawater to enliven the smoothness." Cato liked to drink his wine flavored with a drop of pig's blood and a pinch of marble dust. The archaeologist and winemaker Herve Durad told Bloomberg News, “The soldiers didn't care if it turned to vinegar. It gave them energy." Pliny the Elder also wrote that it was common to find drowned mice in wine-filled storage vessels. When this occurred he suggested removing the marinated mouse and roasting it.

The Romans played drinking games, A depiction of a drinking game in The House of Chaste Lovers in Pompeii shows one person still drinking while another is slumped over a couch, defeated

Estate owners valued their vineyards and inscribed tributes such as “nectar-sweet juices” and “the gift of Bacchus” on their winepresses. Innkeepers inscribed wine lists and prices on the wall of their facilities.

Types of Wine in Ancient Rome

.jpg)

Bar in PompeiiHoneyed wine called mulsum was very popular. This sweet Roman drink — a simple mixture of wine and honey — can ne made today by warm a half cup of clear honey and adding it to a bottle of medium-dry white wine. Chill before serving.

Massilitanum was a heavy wine that Galen regarded as delightful and good for health but Martial thought was so bad it should only be given to homeless people to poison them. At parties the wine was often sprinkled with euphrosynum (“the plant of cheers”) or hiera botane (“the sacred plant”) to keep the conservation going and keep spirits high. In Egypt, people made wine from raisins and dates.

Many of the vineyards in the Moselle Valley in Germany were originally planted by the Romans. Turricuar was a dry white wine the Romans liked to consume with fish and oysters. It was yellowish in color and is spiked with seawater. It tastes slightly of prunes and is made today using a recipe described by Roman agronomist Lucius Columelle.

Falernian wine, grown with Aminean grapes on mountain slopes south of present-day Naples, was particularly prized. To improve its flavor the wine was aged in large clay amphorae for a decade or more until it turned a delicate amber color. A liter cost about $110 in today's money. Premium 160-year-old vintages were reserved for the Emperor and served in crystal goblets. Those that could afford it clearly loved to brag about. One tombstone read: “In the grave I lie. Who was once well known as Primus. I lived on Lucrine oysters, often drank Falernian wines. The pleasures of bathing, wine and love gave me over the years."

The wines from Gaul (France) were said to be “brownish red and sweet with a taste of preach and caramel candy” but left “a nasty hangover.” Even so it seems that the Romans loved it. In 2009, it was announced that a shipwreck dating to the A.D. 2nd century found off Cape Greco, Cyprus contained over 130 ceramic jars, likely to have been carrying wine or oil. The Cyprus Department of Antiquities said “Its location in shallow waters, suggest that either the vessel was nearing an intended port-of-call, or else was engaged in a coasting trade, moving products to market over short distances up and down the coast...While most jars came from South Eastern Asia Minor and the general North East Mediterranean region, one group of amphorae appears to have contained wine imported from the Mediterranean coast of France.” [Source: Patrick Dewhurst, 2009]

In Mas des Tourelles near the Provence town of Beaucair in southern France, a group of archaeologists spent $20,000 to reopen the largest winery in Gaul after 1,800 years. The opened in the early 1990s it sells wine for about $12 a bottle. In Caesar’s time the facility produced the equivalent of 100,000 modern-size bottles of wine a day and each bottle sold for about 1 sesterce (about $1.60). The entire region produced about 27 million liters a year, enough to fill 2 million clay amphorae for shipment by oxen throughout the Mediterranean. [Source: Craig Copetas, Bloomberg News, December 2002]

The Mas des Tourelles wine is brownish red and sweet with a taste of preach and caramel candy but it leaves a nasty hangover. Those who tried it described it as a “curiosity” and said “eat a lot of goat cheese and nuts when you — drink it.

Men used to hang out at wine shops where strong syrupy wine was poured from an amphorae and diluted with water in a large mixing bowl. Rich Greeks and Romans chilled their wine with snow kept in straw lined pits, even though Hippocrates thought that "drinking out of ice" was unhealthy.

The wine from Kos was good and relatively inexpensive. Higher quality wines came from Rhodes. Artemidorus described a drink called “ melogion” which "is more intoxicating than wine" and "made by first boiling some honey with water and then adding a bit of herb." Homer described a drink made from wine, barley meal, honey and goat cheese.

“Kottoabis” is one of the world first known drinking games, A fixture of all-night parties and reportedly even played by Socrates, the game involved flinging the dregs left over from a cup of wine at a target. Usually the participants sat in a circle and tossed their dregs at the basin in the center.

Grapes, Vineyards and Viticulture in the Roman Era

Grapes were eaten fresh from the vines and were also dried in the sun and kept as raisins, but they owed their real importance in Italy as elsewhere to the wine made from them. It is believed that the grapevine was not native to Italy, but was introduced, probably from Greece, in very early times. The first name for Italy known to the Greeks was Oenotria, a name which may mean “the land of the vine”; very ancient legends ascribe to Numa restrictions upon the use of wine. It is probable that up to the time of the Gracchi wine was rare and expensive. The quantity produced gradually increased as the cultivation of cereals declined, but the quality long remained inferior; all the choice wines were imported from Greece and the East. By Cicero’s time, however, attention was being given to viticulture and to the scientific making of wines, and by the time of Augustus vintages were produced that vied with the best brought from abroad. Pliny the Elder says that of the eighty really choice wines then known to the Romans two-thirds were produced in Italy; and Arrian, about the same time, says that Italian wines were famous as far away as India. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Grapes could be grown almost anywhere in Italy, but the best wines were made south of Rome within the confines of Latium and Campania. The cities of Praeneste, Velitrae, and Formiae were famous for the wine grown on the sunny slopes of the Alban hills. A little farther south, near Terracina, was the ager Caecubus, where was produced the Caecuban wine, pronounced by Augustus the noblest of all. Then came Mt. Massicus with the ager Falernus on its southern side, producing the Falernian wines, even more famous than the Caecuban. Upon and around Vesuvius, too, fine wines were grown, especially near Naples, Pompeii, Cumae, and Surrentum. Good wines, but less noted than these, were produced in the extreme south, near Beneventum, Aulon, and Tarentum. Of like quality were those grown east and north of Rome, near Spoletium, Caesena, Ravenna, Hadria, and Ancona. Those of the north and west, in Etruria and Gaul, were not so good. |+|

“The sunny side of a hill was the best place for a vineyard. The vines were supported by poles or trellises in the modern fashion, or were planted at the foot of trees up which they were allowed to climb. For this purpose the elm (ulmus) was preferred, because it flourished everywhere, could be closely trimmed without endangering its life, and had leaves that made good food for cattle when they were plucked off to admit the sunshine to the vines. Vergil speaks of “marrying the vine to the elm,” and Horace calls the plane tree a bachelor (platanus caelebs), because its dense foliage made it unfit for the vineyard. Before the gathering of the grapes the chief work lay in keeping the ground clear; it was spaded over once each month in the year. One man could properly care for about four acres.” |+|

In 2012, Nancy Thomson de Grummond of Florida State University announced that she had discovered some 150 waterlogged grape seeds in a well in Cetamura del Chianti Italy and probably date to about the A.D. 1st century. There is possibility the seeds’ DNA can analyzed. The seeds could provide “a real breakthrough” in the understanding of the history of Chianti vineyards in the area, de Grummond said. “We don’t know a lot about what grapes were grown at that time in the Chianti region.“Studying the grape seeds is important to understanding the evolution of the landscape in Chianti. There’s been lots of research in other vineyards but nothing in Chianti.” [Source: Elizabeth Bettendorf, Phys.org, December 6, 2012]

Ancient Roman Wine Making

Ancient Roman winemakers used tasting spoons and grape presses, some of which are now displayed in museums. Wine was often stored in 26-liter amphorae which had vineyard name and year labeled on them. Estate owners valued their vineyards and inscribed tributes such as “nectar-sweet juices” and “the gift of Bacchus” on their winepresses.

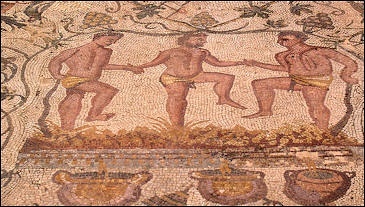

The grapes were usually crushed by foot by slaves, then the mixture was crushed further by a winepress and a stone weight lowered by a tree trunk. The juices flowed down a stem to a waiting pool where it was scooped out and placed in 400-liter clay pots packed with honey, thyme, pepper and other spices. Workers mixed the brew with broomsticks wrapped in fennel. After six days to three weeks in a clay fermentation tub the mixture turned into a foamy red liquid with about 12 percent alcohol. The wine was drinkable for about 10 days before it went bad.

The making of the wine took place usually in September; the season varied with the soil and the climate. It was anticipated by a festival, the vinalia rustica, celebrated on the nineteenth of August. Precisely what the festival meant the Romans themselves did not fully understand, perhaps, but it was probably intended to secure a favorable season for the gathering of the grapes. The general process of making the wine differed little from that familiar to us in Bible stories and still practiced in modern times. After the grapes were gathered, they were first trodden with the bare feet and then pressed in the prelum or torcular. The juice as it came from the press was called mustum (vinum), “new (wine),” and was often drunk unfermented, as sweet cider is now. It could be kept sweet from vintage to vintage by being sealed in a jar smeared within and without with pitch and immersed for several weeks in cold water or buried in moist sand. It was also preserved by evaporation over a fire; when it was reduced one-half in this way, it became a grape jelly (defrutum) and was used as a basis for various beverages and for other purposes. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Fermented wine (vinum) was made by collecting the mustum in huge vat-like jars (dolia). One of these was large enough to hide a man and held a hundred gallons or more. These were covered with pitch within and without and partially buried in the ground in cellars or vaults (vinariae cellae), in which they remained permanently. After they were nearly filled with the mustum, they were left uncovered during the process of fermentation, which lasted under ordinary circumstances about nine days. They were often tightly sealed, and opened only when the wine required attention3 or was to be removed. The cheaper wines were used directly from the dolia; but the choicer kinds were drawn off after a year into smaller jars (amphorae), clarified and even “doctored” in various ways, and finally stored in depositories often entirely distinct from the cellars. A favorite place was a room in the upper story of the house, where the wine was aged by the heat rising from a furnace or even by the smoke from the hearth. The amphorae were often marked with the name of the wine, and the names of the consuls for the year in which they were filled.” |+|

grape crushing

First Wines

Intentional wine-making is believed to have begun in the Neolithic period (from about 9500 to 6000 B.C.) when communities settled in year-round settlements and began intentionally crushing and fermenting grapes and tending a grape crop year round. This is believed to have first occurred in Transcaucasus, eastern Turkey or northwestern Iran. Around the same time the Chinese were making wines with rice and local plant food.

Scholars believe that men may have learned what foods to eat by watching other animals, and through trial and error experimentation. Early man may have discovered early intoxicants and medicines this same way.

Winemaking is believed to have been refined through trial and error. One of the biggest hurdles to overcome was manipulating the yeast that turns grape juice into wine and the bacteria that transforms it into vinegar. Many early wines were mixed with pungent tree resins, presumably to help preserve the wine the absence of corks or stoppers. The resin from the ternith tree, a kind of pistachio, was found in wine dated to 5500 B.C.

There are a number of myths and stories about the first wine. According to the Greeks it was invented by Dionysus and spread eastward to Persia and India. Noah raised grapes after the flood and became so enamored with his product that he became the first town drunk. In a Persian legend, wine was discovered by a concubine of the legendary King Jamsheed, who suffered from splitting headache and accidently drank from jar with spoiled fruit and fell into a deep sleep and awoke cured and feeling refreshed. Afterwards the king ordered his grape stocks to be used to make wine, which was spread around the world.

See Separate Articles FIRST WINES, WINERIES AND ALCOHOLIC DRINKS factsanddetails.com ; EARLIEST BEER factsanddetails.com

"Oldest Wine Ever Discovered" Found in Roman-Era Tomb in Spain

In June 2024, archeologists said they had found the "oldest wine ever discovered" — an urn of wine that is more than 2,000 years old — in a Roman tomb in Carmona, Spain. CBS News reported: A team of chemists at the University of Cordoba recently identified the wine as having been preserved since the first century, researchers said in a study published June 16 in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. The discovery bested the previous record held by a Speyer wine bottle discovered in 1867 that dated back to the fourth century. [Source: S. Dev, CBS News, June 21, 2024]

The urn was used in a funerary ritual that involved two men and two women. As part of the ritual, the skeletal remains of one of the men was immersed in the wine. While the liquid had acquired a reddish hue, a series of chemical tests determined that, due to the absence of a certain acid, the wine was, in fact, white. "At first we were very surprised that liquid was preserved in one of the funerary urns," Juan Manuel Román, the city of Carmona's municipal archaeologist, said in a news release.

Despite millennia having passed, the tomb had been well-sealed and its conditions were therefore extraordinarily intact, protected from floods and leaks, which allowed the wine to maintain its natural state, researchers said. "Most difficult to determine was the origin of the wine, as there are no samples from the same period with which to compare it," the news release said. Still, it was no coincidence that the man's remains were found in the wine. According to the study, women in ancient Rome were prohibited from drinking wine. "It was a man's drink," the release said. "And the two glass urns in the Carmona tomb are elements illustrating Roman society's gender divisions in its funerary rituals."

Flavoring of Roman Wines

Romans in Pompeii flavored their wine — and changed its color — using fava beans. At one remarkably well-preserved “thermopolium” — a snack or wine bar — there archaeologists unearthed fava beans at the bottom jugs of wine in 2020. In many places Romans used dolia to make wine which were buried underground. A study published in January 2024 in Antiquity found that such wines were not unlike some modern wines, especially those made in modern-day Georgia. Recreations of the the dolia winemaking method revealed a drink that was spicy, with nutty flavours and a smell like toast.

Joe Pinkstone wrote in The Telegraph: The most widespread winemaking technique in Italy two centuries ago used a dolium, which is a large earthenware pot with a round body, flat base and wide mouth. There is also a lid, which is only used part of the time. Grapes would be put into the large pots, buried underground with only the top above the surface, and yeasts on the skins would naturally start to make alcohol. This process was widespread throughout the empire and is thought to be the primary method of winemaking in the Roman Empire for hundreds of years. [Source: Joe Pinkstone, The Telegraph, January 23, 2024]

Burying the dolia underground allowed the winemakers precise control on temperature Dr Dimitri Van Limbergen, the study’s lead author and an archaeologist at Ghent University, told The Telegraph: “Ancient wines made from white grapes and made according to techniques we discuss are bound to have tasted oxidative, with complex aromas of toasted bread, dried fruits (apricots, for example), roasted nuts (walnuts, almonds), green tea, and with a very dry and sappy mouth feeling (lots of tannins in the wines from the skins of the grapes). Many Georgian wines are like this and taste fantastic, and are very drinkable (contrary to what you would expect from such complex taste profiles). Fermenting and storing wine in semi-buried clay containers was the most important way of winemaking in the Roman world between the 2nd century B.C. and the 3rd/4th century AD, after which barrels became increasingly used.” The discarded bits of grape at the bottom of the large jugs help stabilise the wine without spoiling it, Dr Limbergen added, helping create an orange hue revered in Roman times.

The burying of the dolia underground allowed the winemakers precise control on temperature, humidity and pH which allowed them to carefully curate the flavour they desired. The process is a controlled version of oxidation but instead of turning an opened bottle of red wine into vinegar, it can lead to desirable flavours if carefully orchestrated. “Controlled oxidation can result in great wines, as it concentrates color and creates pleasant grassy, nutty and dried fruit-like flavours,” the scientists write in their study, published in the journal Antiquity. “The value of identifying, often unexpected, parallels between modern and ancient winemaking lies in both debunking the alleged amateurish nature of Roman winemaking and uncovering common traits in millennia-old vinification procedures,” added Dr Limbergen.

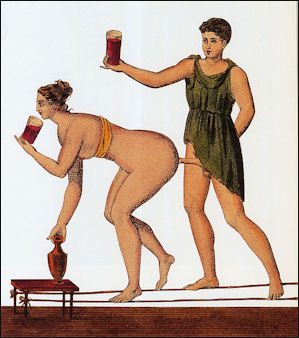

19th century vision of a Greek wine festival

Roman-Era Winemaking Theater Where Audiences Watched People Stomp Grapes

In a study published in the journal Antiquity in April 2023, archaeologist said the Villa of the Quintilii complex, about eight kilometers outside of Rome, had an ornate wine production facility and theater where the upper classes could watch people stomp grapes. “The complex illuminates how ancient elites could fuse utilitarian function with ostentatious luxury to fashion their social and political status,” the authors wrote in their abstract. [Source: Jelisa Castrodale, Food & Wine, April 21, 2023]

Jelisa Castrodale wrote in Food & Wine: Some parts of the facility were characteristic of Roman wineries, including a “grape treading area,” a pair of grape presses and “a system of channels” connecting the above-ground components to a wine cellar. But what wasn’t typical were the luxe materials that were used, and the “decoration and arrangement” of the complex. (The academics who detailed the winery in Antiquity described its as “unparalleled for a production context in the Roman, and perhaps entire ancient, world.”)

“It’s an elite display of associating with the world of peasants and workers,” Emlyn Dodd, an archaeologist at the British School at Rome and one of the study’s co-authors, told Science. “There’s definitely a sense in Roman religion that they try to connect themselves to common people.” (He added that this part of the Villa of the Quintili was “decorated to a stupendous level” and had a “bizarre degree of opulence.”)

The wine-treading area itself was uncharacteristic. Dodd told The Guardian that in most cases, they would be finished with a layer of waterproof concrete, to ensure that grape-squashers could stay on their feet as they stomped. But at the Villa, the stomping section was covered with red marble. “Which isn’t ideal as marble gets incredibly slippery when wet,” he explained to the outlet. “But it shows that whoever built this was prioritizing the extravagant nature of the winery over practical considerations.”

The entire complex covers almost 60 acres, and the winery was discovered by accident when archaeologists were trying to find part of the villa’s former chariot racing track. The Guardian reports that as excavations continued, they discovered that the winery had been constructed later than the track, and was actually built over the starting gates that they were looking for.

Roman-Era Wine Shop Found in Greece and Winery in France

In January 2024, archaeologists announced that they had discovered a 1,600-year-old wine shop that was destroyed and abandoned after a "sudden event," — possibly an earthquake or building collapse — in Greece. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: The shop operated at a time when the Roman Empire controlled the region. It was found in the ancient city of Sikyon (also spelled Sicyon), which is located on the northern coast of the Peloponnese in southern Greece. Within the wine shop, archaeologists found the scattered coins, as well as the remains of marble tabletops and vessels made of bronze, glass and ceramic. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, January 24, 2024]

The wine shop was found on the northern end of a complex that had a series of workshops containing kilns and installations used to press grapes or olives, archaeologists noted in a paper they presented at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America, which was held January 2024 in Chicago. "Unfortunately, we don't have any direct evidence of the types of wine that may have been sold. We have some evidence of grape pips (Vitis vinifera), but we aren't able to say anything more specific than that right now," said Scott Gallimore, an associate professor of archaeology at Wilfrid Laurier University in Canada, who co-wrote the paper with Martin Wells, an associate professor of classics at Austin College.

In addition to wine, other items, such as olive oil, may have been sold in the shop. Most of the coins date to the reign of Constantius II, from 337 to 361, with the latest coin being minted sometime between 355 and 361, Gallimore told Live Science. The wine shop appears to have suffered a "sudden event" that resulted in its destruction and abandonment, Gallimore said. The 60 bronze coins found in the floor are from the shop's final moments. "The coins were all found on the floor of the [shop], scattered across the space," Gallimore said. "This seems to indicate that they were being kept together as some type of group, whether in a ceramic vessel or some type of bag. When the [shop] was destroyed, that container appears to have fallen to the floor and scattered the coins.

In November 2023, archaeologists announced that they had found a ruined winery in southern France in Laveyron — along the Rhône river about 480 kilometers (300 miles) southeast of Paris, the French National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (Inrap) said. The Miami Herald reported: The large-scale winemaking operation was built in the first century A.D. and probably produced drinks for ancient Romans. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, Fri, December 1, 2023]

The 1,900-year-old winery had a central platform where the grapes were pressed, the release said. On either side of the platform, archaeologists found basins where the grape juice was collected. The basins were in turn linked to two larger rooms that archaeologists identified as cellars. A large section of the wall still stands. The construction appears to be made of neatly arranged, rectangular bricks. Excavations also uncovered a three-room building that was likely used for the wine production. The imprints of several large jars, typically used for storing wine or olive oil, were also uncovered. The excavation also found traces of several older buildings, dating to the first century B.C., the institute said. The function of these remains unknown, but a nearby trash heap from the same period revealed fragments of pottery, including the large jars used for wine and olive oil.

Roman Cargo Ship Full of Wine Found off Albania's Coast

In August 2011, a U.S.-Albanian archaeological mission reported that it had found the well-preserved wreck of a Roman cargo ship off Albania's coast, with some 300 wine jars. Associated Press reported: The 30-meter long (yard) wreck dates to the 1st century B.C. and its cargo is believed to have been the produce of southern Albanian vineyards en route to western European markets, including France. [Source: Llazar Semini, Associated Press, August 22, 2011]

A statement from the Key West, Florida-based RPM Nautical Foundation said the find was made 50 meters deep near the port city of Vlora, 140 kilometers (90 miles) southwest of the capital, Tirana. The foundation, in cooperation with Albanian archaeologists, has been surveying a swath of Albania's previously unexplored coastal waters for the past five years. So far, experts have located 20 shipwrecks — including several relatively modern ones. "Taking into consideration the date and also the depth — which is well suited for excavation — I would include it among the top 10 most scientifically interesting wrecks found in the Mediterranean," said Albanian archaeologist Adrian Anastasi, who participated in the project.

Officials said most of the jars, known by their Greek name of amphoras and used to transport wine and oil, were unbroken despite the shipwreck. However, the stoppers used to seal them had gone, allowing their contents to leak out into the saltwater. Mission leader George Robb said the ship could have been part of a flourishing trade in local wine. "Ancient Illyria, which includes present day Albania, was a major source of supply for the western Mediterranean, including present day France and Spain,' Robb said.

Archaeologists Make Wine As the Romans Did

In the 1990s, group of archaeologists spent $20,000 to reopen the largest winery in Gaul — in Mas des Tourelles near the Provence town of Beaucair in southern France — a after 1,800 years, selling the wine for about $12 a bottle. In Caesar's time the facility produced the equivalent of 100,000 modern-size bottles of wine a day and each bottle sold for about 1 sesterce (about $1.60). The entire region produced about 27 million liters a year, enough to fill 2 million clay amphorae for shipment by oxen throughout the Mediterranean. The Mas des Tourelles wine is brownish red and sweet with a taste of preach and caramel candy but it leaves a nasty hangover. Those who tried it described it as a “curiosity” and said “eat a lot of goat cheese and nuts when you drink it.”“ [Source: Craig Copetas, Bloomberg News, December 2002]

Tom Kington wrote in The Guardian: “Archeologists in Italy have set about making red wine exactly as the ancient Romans did, to see what it tastes like. Based at the University of Catania in Sicily and supported by Italy’s national research centre, a team has planted a vineyard near Catania using techniques copied from ancient texts and expects its first vintage within four years. “We are more used to archeological digs but wanted to make society more aware of our work, otherwise we risk being seen as extraterrestrials,” said archaeologist Daniele Malfitana. [Source: Tom Kington, guardian.com, August 22, 2013]

“At the group’s vineyard, which should produce 70 litres at the first harvest, modern chemicals will be banned and vines will be planted using wooden Roman tools and will be fastened with canes and broom, as the Romans did. Instead of fermenting in barrels, the wine will be placed in large terracotta pots – traditionally big enough to hold a man – which are buried to the neck in the ground, lined inside with beeswax to make them impermeable and left open during fermentation before being sealed shut with clay or resin. “We will not use fermenting agents, but rely on the fermentation of the grapes themselves, which will make it as hit and miss as it was then – you can call this experimental archaeology,” said researcher Mario Indelicato, who is managing the programme.

“The team has faithfully followed tips on wine growing given by Virgil in the Georgics, his poem about agriculture, as well as by Columella, a first century A.D. grower, whose detailed guide to winemaking was relied on until the 17th century. “We have found that Roman techniques were more or less in use in Sicily up until a few decades ago, showing how advanced the Romans were,” said Indelicato. “I discovered a two-pointed hoe at my family house on Mount Etna recently that was identical to one we found during a Roman excavation.” What has changed are the types of grape varieties, which have intermingled over the centuries. “Columella mentions 50 types but we can only speculate on the modern-day equivalents,” said Indelicato, who is planting a local variety, Nerello Mascalese.

Pompeii Wine Brought Back to Life

In 2016, The Local reported: “Made from ancient grape varieties grown in Pompeii, ‘Villa dei Misteri’ has to be one of the world’s most exclusive wines. The grapes are planted in exactly the same position, grown using identical techniques and grow from the same soil the city’s wine-makers exploited until Vesuvius buried the city and its inhabitants in A.D. 79. [Source: the local.it, February 2016]

“In the late 1800s, archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli first excavated some of the city’s vineyards from beneath three metres of solid ash. The digs turned up an almost perfect snapshot of ancient wine-growing – and thirteen petrified corpses, huddled against a wall. Casts were made of the bodies, as well as the vines and the surviving segments of trellises on which they were growing. But archaeologists didn’t think to restore the vineyards of ancient Pompeii until the late 1980s.

“When they did, they realized they didn’t have a clue about wine-making, so they called in local winemaker Piero Mastrobeardino. Together they set out to discover how the ancient Romans made wine, and which grapes and farming methods they used. “The team looked at casts of vine roots made two centuries ago and consulted the surviving fragments of ancient farming texts,” Mastrobeardino told The Local. “We even looked at ancient frescoes to try to identify which grapes grew from Pompeii’s soil.” The team discovered that the type of grapes their ancestors were growing, called Piederosso Sciacinoso and Aglianico, were the same varieties still being grown on the slopes of Vesuvius by local farmers. Aglianico is a variety which Piero’s father is credited for saving from extinction after the Second World War.

“Although the grape varieties were still the same, farming techniques had changed significantly since the time of the Romans. “We use a number of methods to grow the fruit and carry out all of the work manually. One thing all our farming techniques have in common is that the grapes are grown at an extremely high density,” Mastrobeardino explained. At first, experts doubted whether the grapes would grow at all at yields almost twice as high as those used today. However, once placed back in Pompeii’s fertile soil, they flourished. Enologists discovered that the Romans’ high-density growth technique is actually beneficial – the technique, now rediscovered, is spreading to the modern wine-making.

“But not everything about ancient wine-making was better. Mastrobeardino ferments the wine according to modern techniques and says Roman wine tasted foul. Pompeii wines were fermented in open-topped terracotta pots, called dolia. These were lined with pine resin filled with wine and buried deep into the earth. Asking a modern wine-lover to drink ancient wine would be foolish. The Romans knew their system was far from perfect but didn’t have the technology to change it.”

“Pompeii wines were considered among the best in the Empire, but were fiercely alcoholic and often diluted with honey, spices and even seawater to mask their rancid flavour. Some 1,500 bottles of Villa dei Misteri are made each year and can be found on the tables of exclusive restaurants in Tokyo, London and New York, Mastrobeardino said. “It’s more of a research project than a commercial enterprise, but it has come a long way. We have now replanted 15 of the city’s ancient vineyards and are experimenting with diverse ancient farming techniques and grape blends.” It might not be a profitable enterprise, but it doesn’t come cheap either – a bottle will set you back around €77.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024