Home | Category: Government and Justice

LEGENDARY GOVERNMENT OF ANCIENT ROME

Roman military punishments included dismemberment

On the government that is said existed after legendary Romulus and Remus, Edward Gibbon wrote in the “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: “The primitive government of Rome was composed, with some political skill, of an elective king, a council of nobles, and a general assembly of the people. War and religion were administered by the supreme magistrate; and he alone proposed the laws, which were debated in the senate, and finally ratified or rejected by a majority of votes in the thirty curiae or parishes of the city. Romulus, Numa, and Servius Tullius, are celebrated as the most ancient legislators; and each of them claims his peculiar part in the threefold division of jurisprudence. [Source: Chapter XLIV: Idea Of The Roman Jurisprudence. Part I. “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” Vol. 4, by Edward Gibbon, 1788, sacred-texts.com]

The laws of marriage, the education of children, and the authority of parents, which may seem to draw their origin from nature itself, are ascribed to the untutored wisdom of Romulus. The law of nations and of religious worship, which Numa introduced, was derived from his nocturnal converse with the nymph Egeria.

The civil law is attributed to the experience of Servius: he balanced the rights and fortunes of the seven classes of citizens; and guarded, by fifty new regulations, the observance of contracts and the punishment of crimes. The state, which he had inclined towards a democracy, was changed by the last Tarquin into a lawless despotism; and when the kingly office was abolished, the patricians engrossed the benefits of freedom. The royal laws became odious or obsolete; the mysterious deposit was silently preserved by the priests and nobles; and at the end of sixty years, the citizens of Rome still complained that they were ruled by the arbitrary sentence of the magistrates. Yet the positive institutions of the kings had blended themselves with the public and private manners of the city, some fragments of that venerable jurisprudence were compiled by the diligence of antiquarians, and above twenty texts still speak the rudeness of the Pelasgic idiom of the Latins.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ROMAN JUSTICE SYSTEM factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN LAW: TYPES, CODES, ORGANIZATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PUNISHMENTS IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN LAWS ON MARRIAGE, PROSTITUTION, FORNICATION, DEBAUCHERY AND ADULTERY factsanddetails.com ;

CRUCIFIXION: HISTORY, EVIDENCE OF IT AND HOW IT WAS DONE europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Oxford Handbook of Roman Law and Society” (Reprint Edition) by Paul J du Plessis. Clifford Ando, Kaius Tuori Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Roman Law” by Barry Nicholas, Ernest Metzger Amazon.com;

“The Republic and The Laws” (Oxford World's Classics) by Cicero Amazon.com;

“The Twelve Tables” Amazon.com;

“The Constitution of the Roman Republic” by Andrew Lintott Amazon.com;

“Patricians and Plebeians: The Origin of the Roman State” by Richard E. Mitchell (1990) Amazon.com;

“Law and Empire in Late Antiquity” by Jill Harries (2001) Amazon.com;

“Human Rights in Ancient Rome” by Richard Bauman Amazon.com;

“A Fatal Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum: Murder in Ancient Rome”

by Emma Southon (2022) Amazon.com

“Policing the Roman Empire: Soldiers, Administration, and Public Order” (Reprint Edition) by Christopher J. Fuhrmann (2011) Amazon.com;

“Roman Law in Context” by David Johnston (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Digest of Roman Law: Theft, Rapine, Damage and Insult (Penguin Classics) by Justinian and C. F. Kolbert (1979) Amazon.com;

“Family and Familia in Roman Law and Life” by Jane F. Gardner (1998) Amazon.com;

“A Casebook on Roman Family Law” by Bruce W. Frier , Thomas A. J. McGinn, et al. | (2003) Amazon.com;

“Law, Language, and Empire in the Roman Tradition” by Clifford Ando (2011) Amazon.com;

“Roman Society and Roman Law in the New Testament” by A. N. Sherwin-White (1961) Amazon.com;

“Roman Scandal: A Brief History of Murder, Adultery, Rape, Slavery, Animal Cruelty, Torture, Plunder, and Religious Persecution in the Ancient Empire of Rome” by Frank H Wallis (2016) Amazon.com;

“Violence in Roman Egypt: A Study in Legal Interpretation” (2013) Amazon.com;

“Invisible Romans: Prostitutes, Outlaws, Slaves, Gladiators, Ordinary Men and Women ... the Romans that History Forgot” by Robert C Knapp (2011) Amazon.com

“Bandits in the Roman Empire: Myth and Reality” by Thomas Grunewald and John Drinkwater | Jul 31, 2004 (2004) Amazon.com

“Prison, Punishment and Penance in Late Antiquity” by Julia Hillner (2015) Amazon.com;

Demand for Written Laws in the 5th Century B.C.

“Proposals of Terentilius Harsa ( B.C. 462): The conflict between the patricians (the elite early Roman aristocracy) and plebeians (early Roman peasants) was a key element of early Roman history. In the mid 5th century B.C. the two orders had struggling with one another for nearly fifty years; and yet no real solution had been found for their difficulties. The plebeians were at a great disadvantage during all this time, because the law was administered solely by the patricians, who kept the knowledge of it to themselves, and who regarded it as a precious legacy from their ancestors, too sacred to be shared with the lowborn plebeians. The laws had never been written down or published. The patricians could therefore administer them as they saw fit. This was a great injustice to the lower classes. It was clear that there was not much hope for the plebeians until they were made equal before the law. It was also clear that they could not be equal before the law as long as they themselves had no knowledge of what the law was. Accordingly one of the tribunes, Gaius Terentilius Harsa, proposed that a commission be appointed to gather up the law, and to publish it to the whole people. This proposal, though both fair and just, was bitterly opposed by the patricians, and was followed by ten years of strife and dissension. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Concessions to the Plebeians: To rescue the city from these troubles, the senate tried to conciliate the plebeians by making certain concessions to them. For example, the number of tribunes was increased from two to five, and then to ten. This was supposed to give them greater protection than they had had before. Then it was decided to give up to them the public land on the Aventine hill, and thus to atone for not carrying out the agrarian law of Sp. Cassius. Finally, the amount of fine which any magistrate could impose was limited to two sheep and thirty oxen. It was thought that such concessions would appease the discontented people and divert their minds from the main point of the controversy. \~\

Compromise between the Plebeians and Patricians: But these concessions did not satisfy the plebeians, who still clung to their demand for equal rights before the law. The struggle over the proposal of Terentilius, which lasted for nearly ten years, was ended only by a compromise. It was finally agreed that a commission of ten men, called decemvirs, should be appointed to draw up the law, and that this law should be published and be binding upon patricians and plebeians alike. It was also agreed that the commissioners should all be patricians; and that they should have entire control of the government while compiling the laws. The patricians were thus to give up their consuls and quaestors; and the plebeians were to give up their tribunes and aediles. Both parties were to cease their quarreling, and await the work of the decemvirs. \~\

Twelve Tables

The Twelve Tables (451-450 B.C.) is the earliest attempt by the Romans to create a code of law; it is also the earliest (surviving) piece of literature coming from the Romans. John Paul Adams of CSUn wrote: “In the midst of a perennial struggle for legal and social protection and civil rights between the privileged class (patricians) and the common people (plebeians) a commission of ten men (Decemviri) was appointed (ca. 455 B.C.) to draw up a code of law which would be binding on both parties and which the magistrates (the 2 consuls) would have to enforce impartially. [Source: “John Paul Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN) , June 10, 2009]

Putting up the Twelve Tables

“The commission produced enough statutes (most of them were already "customary law' anyway) to fill TEN TABLETS, but this attempt seems not to have been entirely satisfactory — especially to the plebeians. A second commission of ten was therefore appointed (450 B.C.) and two additional tablets were drawn up. The originals, said to have been inscribed on bronze, were probably destroyed when the Gauls sacked and burned Rome in the invasion of 387 B.C.

“The Twelve Tables give the student of Roman culture a chance to look into the workings of a society which is still quite agrarian in outlook and operations, and in which the main bonds which hold the society together and allow it to operate are: the clan (genos, gens), patronage (patron/client), and the inherent (and inherited) right of the patricians to leadership (in war, religion, law, and government). Cicero wrote in De Oratore, I.44: “Though all the world exclaim against me, I will say what I think: that single little book of the Twelve Tables, if anyone look to the fountains and sources of laws, seems to me, assuredly, to surpass the libraries of all the philosophers, both in weight of authority, and in plenitude of utility.”

TABLE I: Procedure: for courts and trials

TABLE II: Trials, continued

TABLE III: Debt

TABLE IV: Rights of fathers (paterfamilias) over the family

TABLE V: Legal guardianship and inheritance laws

TABLE VI: Acquisition and possession

TABLE VII: Land rights

TABLE VIII: Torts and delicts (Laws of injury)

TABLE IX: Public law

TABLE X: Sacred law

TABLE XI: Supplement I

TABLE XII: Supplement II

Edward Gibbon wrote in the “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”: “Whatever might be the origin or the merit of the twelve tables, they obtained among the Romans that blind and partial reverence which the lawyers of every country delight to bestow on their municipal institutions. The study is recommended by Cicero as equally pleasant and instructive. "They amuse the mind by the remembrance of old words and the portrait of ancient manners; they inculcate the soundest principles of government and morals; and I am not afraid to affirm, that the brief composition of the Decemvirs surpasses in genuine value the libraries of Grecian philosophy. How admirable," says Tully, with honest or affected prejudice, "is the wisdom of our ancestors!...The twelve tables were committed to the memory of the young and the meditation of the old; they were transcribed and illustrated with learned diligence; they had escaped the flames of the Gauls, they subsisted in the age of Justinian, and their subsequent loss has been imperfectly restored by the labors of modern critics. [Source: Chapter XLIV: Idea Of The Roman Jurisprudence. Part II, “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” Vol. 4, by Edward Gibbon, 1788, sacred-texts.com]

RELATED ARTICLE: See Twelve Tables Under EARLY ROMAN REPUBLIC: ITS FOUNDING, DEVELOPMENT AND EXPANSION europe.factsanddetails.com

Cicero and Improvements to Roman Law in the 1st and 2nd Centuries B.C.

The Roman general and dictator Sulla (138-78 B.C.) organized the criminal courts for the trial of public crimes. In the 1st and 2nd centuries B.C. there were also improvements made in the civil law, by which the private rights of individuals were better protected. Not only were the rights of citizens made more secure, but the rights of foreigners were also more carefully guarded. Before the social war, the rights of all foreigners in Italy were protected by a special praetor (praetor peregrinus); and after that war all Italians became equal before the law. There was also a tendency to give all foreigners in the provinces rights equal to those of citizens, so far as these rights related to persons and property. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The Roman general and dictator Sulla (138-78 B.C.) organized the criminal courts for the trial of public crimes. In the 1st and 2nd centuries B.C. there were also improvements made in the civil law, by which the private rights of individuals were better protected. Not only were the rights of citizens made more secure, but the rights of foreigners were also more carefully guarded. Before the social war, the rights of all foreigners in Italy were protected by a special praetor (praetor peregrinus); and after that war all Italians became equal before the law. There was also a tendency to give all foreigners in the provinces rights equal to those of citizens, so far as these rights related to persons and property. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

In addition to being an influential politician, Cicero (Marcus Tullius Cicero, 106-43 B.C.) was also the most celebrated defense lawyer of his time –- a Roman Johnny Cochran or F. Lee Bailey if you will. He was famous for winning shaky cases with his extraordinary persuasive skills. He once won a Greek poet Roman citizenship, even though he had documents to prove it, by waxing eloquently about contributions poets make to society. Cicero once said, "We are brought in not to say what we stand by in our own opinions, but what is called for by circumstances and the case itself" and if necessary "to pour darkness over the judges."

Cicero pioneered standard defense tactics such as the praeterito (a technique in which the lawyer condemns his opponents while he insists he doing no such thing) and the ad misericordiam (an appeal of pity in which the defendants crying wife and malnourished children were positioned in front of the jury box). If Ciceros client was childless he would hire some homeless children to play the part. In the classic example of a praeterito, the lawyer would say he wants the jury to make their decision based totally on evidence and the fact that the prosecutor cheats on wife and is cruel to his dog.

Age of Jurisprudence in Ancient Rome

Edward Gibbon wrote in the “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”: The splendid age of jurisprudence, may be extended from the birth of Cicero (106–43 B.C.) to the reign of Severus Alexander (ruled A.D. 222–235). A system was formed, schools were instituted, books were composed, and both the living and the dead became subservient to the instruction of the student. The tripartite of Aelius Paetus, surnamed Catus, or the Cunning, was preserved as the oldest work of Jurisprudence. [Source: Chapter XLIV: Idea Of The Roman Jurisprudence. Part IV, “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” Vol. 4, by Edward Gibbon, 1788, sacred-texts.com]

“The jurisprudence which had been grossly adapted to the wants of the first Romans, was polished and improved... by the alliance of Grecian philosophy...Servius Sulpicius (105– 43 B.C.) was the first civilian who established his art on a certain and general theory. For the discernment of truth and falsehood he applied, as an infallible rule, the logic of Aristotle and the stoics, reduced particular cases to general principles, and diffused over the shapeless mass the light of order and eloquence.

Cicero, his contemporary and friend, declined the reputation of a professed lawyer; but the jurisprudence of his country was adorned by his incomparable genius, which converts into gold every object that it touches. After the example of Plato, he composed a republic; and, for the use of his republic, a treatise of laws; in which he labors to deduce from a celestial origin the wisdom and justice of the Roman constitution. The whole universe, according to his sublime hypothesis, forms one immense commonwealth: gods and men, who participate of the same essence, are members of the same community; reason prescribes the law of nature and nations; and all positive institutions, however modified by accident or custom, are drawn from the rule of right, which the Deity has inscribed on every virtuous mind.

From the portico” of Greek philosophy, “the Roman civilians learned to live, to reason, and to die: but they imbibed in some degree the prejudices of the sect; the love of paradox, the pertinacious habits of dispute, and a minute attachment to words and verbal distinctions. The superiority of form to matter was introduced to ascertain the right of property: and the equality of crimes is countenanced by an opinion of Trebatius, that he who touches the ear, touches the whole body; and that he who steals from a heap of corn, or a hogshead of wine, is guilty of the entire theft.”

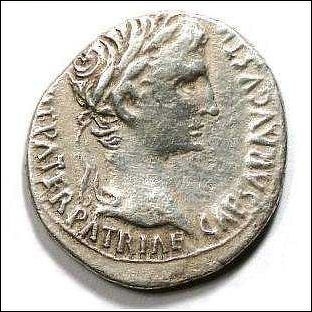

Judicial Reforms and Improvements Under Augustus

Augustus gave judges more authority, established the concept of precedence as a cornerstone of justice and helped engender respect for government institutions. His rule though could be harsh. Augustus is reported to have ordered that his executions be carried out "quicker than you can cook asparagus."

Augustus

Suetonius wrote: “Many pernicious practices militating against public security had survived as a result of the lawless habits of the civil wars, or had even arisen in time of peace. Gangs of footpads openly went about with swords by their sides, ostensibly to protect themselves, and travellers in the country, freemen and slaves alike, were seized and kept in confinement in the workhouses [the ergastula were prisons for slaves, who were made to work in chains in the fields] of the land owners; numerous leagues, too, were formed for the commission of crimes of every kind, assuming the title of some new guild [collegia, or guilds, of workmen were allowed and were numerous; not infrequently they were a pretext for some illegal secret organization]. Therefore to put a stop to brigandage, he stationed guards of soldiers wherever it seemed advisable, inspected the workhouses, and disbanded all guilds, except such as were of long standing and formed for legitimate purposes. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum — Divus Augustus” (“The Lives of the Caesars — The Deified Augustus”), written A.D. c. 110, “Suetonius, De Vita Caesarum,” 2 Vols., trans. J. C. Rolfe (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1920), pp. 123-287]

“He burned the records of old debts to the treasury, which were by far the most frequent source of blackmail. He made over to their holders places in the city to which the claim of the state was uncertain. He struck off the lists the names of those who had long been under accusation, from whose humiliation nothing was to be gained except the gratification of their enemies, with the stipulation that if anyone was minded to renew the charge, he should be liable to the same penalty [i.e., if he failed to win his suit, he should suffer the penalty that would have been inflicted on the defendant, if he had been convicted]. To prevent any action for damages or on a disputed claim from falling through or being put off, he added to the term of the courts thirty more days, which had before been taken up with honorary games. To the three divisions of jurors he added a fourth of a lower estate, to be called ducenarii, and to sit on cases involving trifling amounts. He enrolled as jurors men of thirty years or more, that is five years younger than usual. But when many strove to escape court duty, he reluctantly consented that each division in turn should have a year's exemption, and that the custom of holding court during the months of November and December should be given up.

“He himself administered justice regularly and sometimes up to nightfall, having a litter placed upon the tribunal, if he was indisposed, or even lying down at home. In his administration of justice he was both highly conscientious and very lenient; for to save a man clearly guilty of parricide from being sewn up in the sack [parricides were sewn up in a sack with a dog, a cock, a snake, and a monkey, and thrown into the sea or a river], a punishment which was inflicted only on those who pleaded guilty, he is said to have put the question to him in this form: "You surely did not kill your father, did you?" Again, in a case touching a forged will, in which all the signers were liable to punishment by the Cornelian Law, he distributed to the jury not merely the two tablets for condemnation or acquittal, but a third as well, for the pardon of those who were shown to have been induced to sign by misrepresentation or misunderstanding. Each year he referred appeals of cases involving citizens to the city praetor, but those between foreigners to ex-consuls, of whom he had put one in charge of the business affairs of each province.”

Legal Reforms Under Vespasian

Vespasian

Suetonius wrote: “Lawsuit upon lawsuit had accumulated in all the courts to an excessive degree, since those of longstanding were left unsettled though the interruption of court business [During the civil wars] and new ones had arisen through the disorder of the times. He therefore chose commissioners by lot to restore what had been seized in time of war, and to make special decisions in the Court of the Hundred, reducing the cases to the smallest possible number, since it was clear that the lifetime of the litigants would not suffice for the regular proceedings. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum: Vespasian” (“Life of Vespasian”), written c. A.D. 110, translated by J. C. Rolfe, Suetonius, 2 Vols., The Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.281-321]

“Licentiousness and extravagance had flourished without restraint; hence he induced the Senate to vote that any woman who formed a connection with the slave of another person should herself be treated as a bond-woman; also that those who lend money to minors [In the legal sense; "filii familiarum" were sons who were still under the control of their fathers, regardless of their age; cf., Tib. xv.2] should never have a legal right to enforce payment, that is to say, not even after the death of the fathers.

“It cannot readily be shown that any innocent person was punished save in Vespasian's absence and without his knowledge, or at any rate against his will and by misleading him. Although Helvidius Priscus was the only one who greeted him on his return from Syria by his private name of "Vespasian," and moreover in his praetorship left the emperor unhonored and unmentioned in all his edicts, he did not show anger until by the extravagance of his railing Helvidius had all but degraded him. But even in his case, though he did banish him and later order his death, he was most anxious for any means of saving him, and sent messengers to recall those who were to slay him; and he would have saved him, but for a false report that Helvidius had already been done to death. Certainly he never took pleasure in the death of anyone, but even wept and sighed over those who suffered merited punishment.

Hadrian’s Legal Reforms

Perhaps the most important event in the reign of Hadrian was his compilation of the best part of the Roman law. Since the XII. Tables there had been no collection of legal rules. That ancient code was framed upon the customs of a primitive people. It did not represent the actual law by which justice was now administered. A new and better law had grown up in the courts of the praetors and of the provincial governors. It had been expressed in the edicts of these magistrates; but it had now become voluminous and scattered. Hadrian delegated to one of his jurists, Salvius Julianus, the task of collecting this law into a concise form, so that it could be used for the better a ministration of justice throughout the empire. This collection was called the Perpetual Edict (Edictum Perpetuum). [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Hadrian dressed like a Greek

Tom Dyckoff wrote in The Times: “Hadrian could lay claim to being the world’s first conservationist – passing laws curbing unnecessary demolition – and urban regenerator, involving himself in the minutiae of neighbourhood politics, and recognising the civilising effects on his populace of a decent, unpotholed pavement, laws banning heavy traffic and a good flood prevention policy.” [Source: Tom Dyckoff, the Times, July 2008]

Aelius Spartianus wrote: “He always inquired into the actions of all his judges, and persisted in his inquiries until he satisfied himself of the truth about them. He would not allow his freedmen to be prominent in public affairs or to have any influence over himself, and he declared that all his predecessors were to blame for the faults of their freedmen; he also punished all his freedmen who boasted of their influence over him. With regard to his treatment of his slaves, the following incident, stern but almost humorous, is still related. Once when he saw one of his slaves walk away from his presence between two senators, he sent someone to give him a box on the ear and say to him: "Do not walk between those whose slave you may some day be." As an article of food he was singularly fond of tetrapharmacum, which consisted of pheasant, sow's udders, ham, and pastry. [Source: Aelius Spartianus: Life of Hadrian,” (r. 117-138 CE.),William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

“He established a regular imperial post, in order to relieve the local officials of such a burden. Moreover, he used every means of gaining popularity. He remitted to private debtors in Rome and in Italy immense sums of money owed to the privy-purse, and in the provinces he remitted large amounts of arrears; and he ordered the promissory notes to be burned in the Forum of the Deified Trajan, in order that the general sense of security might thereby be increased. He gave orders that the property of condemned persons should not accrue to the privy-purse, and in each case deposited the whole amount in the public treasury. He made additional appropriations for the children to whom Trajan had allotted grants of money. He supplemented the property of senators impoverished through no fault of their own, making the allowance in each case proportionate to the number of children, so that it might be enough for a senatorial career; to many, indeed, he paid punctually on the date the amount allotted for their living. Sums of money sufficient to enable men to hold office he bestowed, not on his friends alone, but also on many far and wide, and by his donations he helped a number of women to sustain life. He gave gladiatorial combats for six days in succession, and on his birthday he put into the arena a thousand wild beasts.”

Legal and Administrative Improvements Under Antoninus Pius

His Influence upon Law and Legislation: If we should seek for the most distinguishing feature of his reign, we should doubtless find it in the field of law. His high sense of justice brought him into close relation with the great jurists of the age, who were now beginning to make their influence felt. With them he believed that the spirit of the law was more important than the letter. One of his maxims was this: “While the forms of the law must not be lightly altered, they must be interpreted so as to meet the demands of justice.” He laid down the important principle that everyone should be regarded as innocent until proved guilty. He mitigated the evils of slavery, and declared that a man had no more right to kill his own slave than the slave of another. It was about the close of his reign that the great elementary treatise on the Roman law, called the “Institutes” of Gaius, appeared. \~\

Antoninus Pius

Roman Jurisprudence: Some one has said that the greatest bequests of antiquity to the modern world were Christianity, Greek philosophy, and the Roman law. We should study the history of Rome to little purpose if we failed to take account of this, the highest product of her civilization. It is not to her amphitheaters, her circuses, her triumphal arches, or to her sacred temples that we must look in order to see the most distinctive and enduring features of Roman life. We must look rather to her basilicas—that is, her courthouses where the principles of justice were administered to her citizens and her subjects in the forms of law. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

The Government and Administration: It was during the period of the Antonines that the imperial government reached its highest development. This government was, in fact, the most remarkable example that the world has ever seen of what we may call a “paternal autocracy”—that is government in the hands of a single ruler, but exercised solely for the benefit of the people. In this respect the ideals of Julius and Augustus seem to have been completely realized. The emperor was looked upon as the embodiment of the state, the personification of law, and the promoter of justice, equality, and domestic peace. Every department of the administration was under his control. He had the selection of the officials to carry into execution his will. The character of such a government the Romans well expressed in their maxim, “What is pleasing to the prince has the force of law.”

Constantine, Christianity and Roman Law

Roman emperor Constantine (A.D. 312-37) is generally known as the “first Christian emperor.” Michael J. The foundations of the medieval church were laid by the Constantine who first made the Christian faith legal and then made it his own. In 392 Christianity became the official religion of the empire.

In March 313, Constantine issued his famous Edict of Milan which gave every person the right to practice any religion they wanted. With the edict Constantine formally recognized Christianity and put an end to the persecution of Christians. In 324, Constantine made Christianity the state religion: stating there was "No distinction between realm of Caesar and the realm of God." Under Constantine, pagan temples were expropriated, their treasuries were used to build churches and support clergy, and laws were adjusted for Christian ethics.

Hans A. Pohlsander of SUNY wrote: ““In February 313, probably, Constantine and Licinius met at Milan. On this occasion Constantine's half-sister Constantia was wed to Licinius. Also on this occasion, the two emperors formulated a common religious policy. Several months later Licinius issued an edict which is commonly but erroneously known as the Edict of Milan. Unlike Constantine, Licinius did not commit himself personally to Christianity; even his commitment to toleration eventually gave way to renewed persecution. Constantine's profession of Christianity was not an unmixed blessing to the church. Constantine used the church as an instrument of imperial policy, imposed upon it his imperial ideology, and thus deprived it of much of the independence which it had previously enjoyed.” [Source: Hans A. Pohlsander, SUNY Albany, Roman Emperors]

See Separate Article: PRO-CHRISTIAN LAWS AND REFORMS ENACTED BY CONSTANTINE THE GREAT europe.factsanddetails.com

Justinian and the Codex Justinianus

Byzantine emperor Justinian I (ruled A.D. 527-565), also known as Justinian the Lawmaker, was famous for creating the first codified legal book, the “Institutes”, later known as the “Codex Justinianus 529" or simply “The Digest”. This legal textbook, which became the law of the land for almost 1000 years, was created with a hand-picked group of lawyers and synthesized from 2000 books of Roman law. Justinian gave us the word "justice." He was born into a peasant family in 482 and rose through the ranks with the help of his uncle. Justinian also changed the face of money by putting his likeness on one side of a coin and the image of Christ on the other. He made an effort to root out corruption and make law more understandable and accessible.

When the Roman empire moved to Byzantium (a Greek name) the official language of the empire was changed from Latin to Greek and Roman Law was condensed into the "Codex Justinianus 529", a document that defined the legal code in Europe through the Middle Ages. The Codex Justinianus (Latin for "The Code of Justinian") is one part of the Corpus Juris Civilis, the codification of Roman law ordered early in the 6th century AD by Justinian I, who was an Eastern Roman (Byzantine) emperor based in Constantinople. Two other units, the Digest and the Institutes, were created during his reign. The fourth part, the Novellae Constitutiones (New Constitutions, or Novels), was compiled unofficially after his death but is now thought of as part of the Corpus Juris Civilis [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Article: ROMAN LAW: TYPES, CODES, ORGANIZATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024