Home | Category: Religion and Gods

MAGIC IN ANCIENT ROME

magic items

Magic in the context of ancient Rome refers to supernatural practices, often undertaken by individuals privately, that were not overseen by official priesthoods. Private magic was practiced throughout Greek and Roman cultures as well as among Jews and early Christians of the Roman Empire. Primary sources for the study of Greco-Roman magic include the Greek Magical Papyri, curse tablets, amulets, and literary texts such as Ovid's Fasti and Pliny the Elder's Natural History. [Source Wikipedia]

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: A striking development of the imperial period was that the concept of magic emerged as the ultimate superstition, a system whose principles were parodic of and in opposition to true religio. According to the encyclopedia of Pliny the Elder, magic, which originated in Persia, was a heady combination of medicine, religion, and astrology that met human desires for health, control of the gods, and knowledge of the future. The system was, in his view, totally fraudulent (Natural History 30.1-18; cf. Lucan's Pharsalia 6.413-830). Such views of magic as a form of deviant religious behavior should also be related to the developing concepts and practices of Roman law in the imperial period. The speech by Apuleius (De magia) defending himself against a charge of bewitching a wealthy heiress in a North African town is particularly important.

The relationship of this stereotype to the reality of magical practice is, however, complex. Magic was an important part of the fictional repertoire of Roman writers, but it was not only a figment of the imagination of the elite; and its practice may have become more prominent through the principate — a consequence perhaps of it too (like other forms of knowledge) becoming partially professionalized in the hands of literate experts in the imperial period. So, for example, the surviving Latin curses (often scratched on lead tablets, and so preserved) increase greatly in number under the Empire, and the Greek magical papyri from Egypt are most common in the third and fourth centuries ce. Roman anxieties about magic may, in part, have been triggered by changes in its practices and prominence, as well as by the internal logic of their own worldview.

Hans Dieter Betz (born 1931), an American scholar of the New Testament and Early Christianity at the University of Chicago has argued that in general magic was held in low esteem and condemned by writers and people of authority. Betz eludes to book burnings in regards to texts such as the Greek Magical Papyri, when he cites Ephesus in the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 19: 19). Suetonius, Augustus ordered the burning of 2,000 magical scrolls in 13 B.C. Betz states: As a result of these acts of suppression, the magicians and their literature went underground. The papyri themselves testify to this by the constantly recurring admonition to keep the books secret. [...] The religious beliefs and practices of most people were identical with some form of magic, and the neat distinctions we make today between approved and disapproved forms of religion — calling the former "religion" and "church" and the latter "magic" and "cult" — did not exist in antiquity except among a few intellectuals. It is known that philosophers of the Neopythagorean and Neoplatonic schools, as well as Gnostic and Hermetic groups, used magical books and hence must have possessed copies. But most of their material vanished and what we have left are their quotations.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ROMAN SUPERSTITIONS, DIVINATION AND ASTROLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Magic and Magicians in the Greco-Roman World” by Matthew W. Dickie (2002) Amazon.com;

“Magic and Religion in the Ancient Mediterranean World” by Radcliffe G. Edmonds III and Carolina López-Ruiz (2023) Amazon.com

“Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds: a Collection of Ancient Texts” by Georg Luck (1985) Amazon.com;

“Material Approaches to Roman Magic: Occult Objects and Supernatural Substances” by Adam Parker and Stuart McKie (2018) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Necromancy” by Daniel Ogden (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Divine Liver: The Art And Science Of Haruspicy As Practiced By The Etruscans And Romans” by Rev. Robert Lee Ellison (2013) Amazon.com;

“Magic in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Lindsay C. Watson Amazon.com;

“Ancient Magic: A Practitioner's Guide to the Supernatural in Greece and Rome” by Philip Matyszak (2019) Amazon.com;

"Magic, Witchcraft and Ghosts in the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Sourcebook"

by Daniel Ogden (2009) Amazon.com;

“Superstition In Roman Society” by Samuel Dill (1844-1924) Amazon.com;

“Superstitious Beliefs And Practices Of The Greeks And Romans” by William Reginald Halliday (1886-1966) Amazon.com;

“Religious Deviance in the Roman World: Superstition or Individuality?” by Jörg Rüpke and David M. B. Richardson (2016) Amazon.com;

“Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World” by John G. Gager (1999) Amazon.com;

“Votive Body Parts in Greek and Roman Religion” by Jessica Hughes (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Dancing Lares and the Serpent in the Garden: Religion at the Roman Street Corner” by Harriet I. Flower (2017) Amazon.com;

“Senses, Cognition, and Ritual Experience in the Roman World” by Blanka Misic, Abigail Graham (2024) Amazon.com;

“Religions of Rome: Volume 1: A History” by Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price ( Amazon.com;

“Religions of Rome: Volume 2: A Sourcebook” by Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price ( Amazon.com;

"Archaic Roman Religion, Volume 1 Paperback by Georges Dumézil, Philip Krapp (1996) Amazon.com;

“Archaic Roman Religion, Volume 2" by Georges Dumézil (1996) Amazon.com;

Witchcraft and Sorcery in Ancient Rome

consultation with a witch The impression one gets from ancient Roman literary texts is that there were professional witches working in Rome. In his novel “Metamorphoses” the A.D. 2nd century author Apuleius wrote: “First she arranged the deadly laboratory with its customary apparatus, setting out spices of all sorts, unintelligibly lettered metal plaques, the remains of ill-omened birds, and numerous pieces of mourned and even buried corpses: here noses and fingers, there flesh-covered spikes from crucified bodies; elsewhere they preserved gore or murder victims and mutilated skulls wrenched from the teeth of wild beasts. Then she recited a charm over some pulsating entrails and made offerings with various liquids . . . next she bound and knotted those hairs together in interlocking braids and put them to burn on live coals along with several kinds of incense."

Romans believed in the evil eye, sex-changes, the power of iron and menstrual blood and the evil nature of odd numbers. Sorcerers used a ouija board-like bronze table with symbols that were pointed to a ring hanging from a thread. Apuleius, author of the Golden Ass, a book about magic, was tried in court for bewitching his wife, a wealthy widow. ["World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Ancient writings suggest that professional witches worked in Rome, and the second-century A.D. author Apuleius wrote a detailed description of one casting an evil spell, equipped with "spices of all sorts, the remains of ill-omened birds, and numerous pieces of mourned and even buried corpses: here noses and fingers, there flesh-covered spikes from crucified bodies …"[Source Tom Metcalfe Live Science, August 23, 2022]

Archaeologists have found Roman voodoo dolls in lead canisters. Most magic, it seems, was oriented towards cursing people or compelling them to fall in love. Hecate was the Roman goddess of witchcraft. She is sometimes depicted with long dark hair, wearing a long dark dress, accompanied by the mournful owl of false wisdom, a thistle-eating donkey,the head of a crocodile (blood-thirsty hypocrisy) and a cat-headed bat.

2,000-Year-Old Book of Spells Found in Roman Serbia

In 2016, archaeologists announced they had discovered what they believe is a 2,000-year-old book of "spells", etched onto tiny rolls of gold and silver, in a grave alongside skeletons in northeastern Serbia. The archaeologists had difficulty deciphering the language on the scrolls, and were not sure if the spells were intended for good or for evil. “"We read the names of a few demons that are connected to the territory of modern-day Syria," archaeologist Ilija Dankovic told Reuters. [Source: This Week, August 10, 2016]

magic book

This Week reported: “The scrolls were discovered inside two lead amulets, and appear to have been similar in use to "binding magic" practiced in other cultures. Such charms were typically buried with people who had died violently because the "souls of such people took longer to find rest and had a better chance of finding demons and deities and pass the wishes to them so they could do their magic," Dankovic said.

“Binding magic could be used to make someone fall in love, but it could also be used for "dark, malignant curses, to the tune of 'May your body turn dead, as cold and heavy as this lead,'" Dankovic said. For the time being, the purpose of the spells remains a mystery and it may never be fully understood; while the alphabet is written in Greek letters, the language is Aramaic. "It's a Middle Eastern mystery to us,” Miomir Korac, the chief archaeologist at the site, told Reuters.”

Abracadabra

Tom Metcalfe wrote in National Geographic: Abracadabra first appears in the writings of Quintus Serenus Sammonicus more than 1,800 years ago as a magical remedy for fever, a potentially fatal development in an age before antibiotics and a symptom of malaria. He was a tutor to the children who became the Romam emperors Geta and Caracalla, and his privileged position in a wealthy noble family added importance to his words. [Source Tom Metcalfe, National Geographic, March 2,2024]

Writing in in the second century A.D. in a book called Liber Medicinalis (“Book of Medicine”) Serenus advised making an amulet containing parchment inscribed with the magical word, to be hung around the neck of a sufferer. He prescribed that the word be written on subsequent lines, but in a downwards-pointing triangle with one less letter each time:

ABRACADABRA

ABRACADABR

ABRACADAB...

The inscription would then consist of 11 lines, written until there were no characters left in the word; and in the same way, Serenus said, the fever would also disappear.

According to recent research, versions of abracadabra also appear in an Egyptian papyrus written in Greek from the third century A.D., which omits the vowels at the start and end of abracadabra in subsequent lines; and in a Coptic codex from the sixth century, which uses the same method but a different magical word.

For followers of Greek magic, writing variations of a word in a downwards-pointing triangle formed a “grape-cluster” or “heart shape,” which was a way of writing down an oral incantation that repeated and diminished the name of an evil spirit in the same way. Such spirits were thought to cause diseases, and both these versions of the abracadabra spell were supposed to cure fevers and other ailments.

Abracadabra was an “apotropaic — a word that could avert bad things,” explains Elyse Graham, a historian of language at Stony Brook University, noting that its origins have been much debated. Some think abracadabra comes from the Hebrew phrase “ebrah k’dabri,” and means “I create as I speak,’” while others think it comes from “avra gavra,” an Aramaic phrase meaning “I will create man” — the words of God on the sixth day of creation. Still others note its similarity to “avada kedavra’, the “Killing Curse” in the Harry Potter books, which author J.K Rowling has said is Aramaic for “let the thing be destroyed.”

Medieval historian Don Skemer, a specialist in magic and former curator of manuscripts at Princeton University, suggests abracadabra could derive from the Hebrew phrase “ha brachah dabarah,” which means “name of the blessed” and was regarded as a magical name. “I think this explanation is plausible because divine names are important sources of supernatural power to protect and heal, as we see in ancient, medieval, and modern magic,” he says; for early Christians “names derived from Hebrew enjoyed high standing because Hebrew was the language of God and Creation,” Skemer adds.

Amulets and Protective Magic Objects

magic talisman

Little babies were tightly bound in swaddling clothes soon after birth, and their mothers, in anxiety for their child’s safety, usually fastened an amulet or charm of some kind around their neck to keep away unfriendly spirits. The grotesque faces of colored glass on such amulets may have served this purpose. Roman children wore the bulla, a case of leather or gold, according to the means of the parents, containing a charm. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Hawkers sold amulets on the streets. There were specials amulets that invoked specific gods for almost every need. Among the bestsellers were amulets of the gods protecting babies: Wailer, Breast-feeder, Eater and Stander. Romans wore phalluses as good luck charms. One of the good luck charms of ancient Rome was the phallus—a very Latin way to say erect penis. “There’s evidence that the phallic symbolism was a very integral part of Roman life. They wore phallus charms as necklaces, hung them in their doorways, and even made wind chimes to ward off evil spirits. Sometimes the phallus was embellished as well—those wind chimes have been found with the feet of a lion, the wings of a bird, and the head of, well, a penis. If someone hung that up in their house today, they’d probably be arrested as a sex offender.” [Source: Andrew Handley, Listverse, February 8, 2013]

A 13-centimeter (5-inch) -wide, five-centimeter (2-inch) tall Roman ritual deposit bowl, dated the A.D. late1st or early 2nd century and made of pottery, eggshell, bronze, iron, stone was unearthed in Sardis, western Turkey. It was designed to contain magical objects

According to Archaeology magazine: “It was a dangerous year for the inhabitants of Sardis. In A.D. 17 an earthquake, which the ancient historian Pliny called “the greatest earthquake in human memory,” destroyed the great city, once the capital of the Lydian Empire and, at the time, a Roman imperial provincial capital. It took the Sardians decades to rebuild — but they weren’t taking any chances. Members of Harvard University’s Sardis project recently discovered a simple, locally produced bowl, with a similar bowl used as a cover, that had been buried under the floor of a domestic or public space sometime after A.D. 65. Inside the bowl was a collection of artifacts that project archaeologist Elizabeth DeRidder Raubolt of the University of Missouri describes as having been used for rituals of “protective magic.” These included an eggshell, which she describes as “about the size of medium organic egg, not the jumbo or extra large ones,” as well as a bronze needle perhaps used for piercing the eggshell, a pebble, iron implements, a bronze nail, and a bronze coin. [Source: Archaeology magazine, May-June 2014]

“As is perhaps appropriate in the city that Herodotus tells us was the first to mint coinage in the seventh century B.C., it is the coin that provides the most compelling evidence of the Sardians’ desire to avoid another disastrous event. The bronze coin, which dates to between A.D. 62 and 65, depicts the emperor Nero on the obverse, and, on the reverse, an image of the god Zeus Lydios, a native deity of storms and thunder. “Clearly the Sardians chose this coin specifically as a plea for there to be no more earthquakes,” says DeRidder Raubolt.

Roman-Era Evil Eye Jewelry Found on Young Girl in Israel

In April 2023, archaeologists announced that they had found jewelry designed to ward off the “evil eye” and protect a young girl in her passage to the afterlife more than 1,800 years in Jerusalem. Patrick Smith of NBC News wrote: The treasure — which includes golden earrings, a hairpin, a pendant and glass and gold beads bearing the symbols of the Roman Moon goddess Luna — was discovered in a lead coffin in 1971, but has only now gone on display for the first time in a new exhibition, the Israel Antiquities Authority. [Source: Patrick Smith, NBC News, April 4, 2023]

The jewelry would have been worn by the girl during her life and placed in her coffin to keep her safe, a common pagan practice that shows the diversity of late Roman Jerusalem, experts said. “The interring of the jewelry together with the young girl is touching. One can imagine that their parents or relatives parted from the girl, either adorned with the jewelry, or possibly lying by her side, and thinking of the protection that the jewelry provided in the world to come,” said Eli Escusido, director of the Israel Antiquities Authority. “This is a very human situation, and all can identify with the need to protect one’s offspring, whatever the culture or the period,” he added.

The coffin was found on Mount Scopus, in the northeast of the city. The belief in a malevolent “evil eye” dates back more than 2,000 years: Cups bearing an eye and thought to be related to the folk belief have been found from the mid-sixth century B.C. The Greek philosopher Plutarch, who lived in the first century, wrote that the human eye could release energy powerful enough to kill small animals and children. The superstition is still prevalent in some Mediterranean cultures. Some wear eye pendants to protect them against a curse given to them by someone’s malicious glare. The same blue eye trinkets can be seen in countless tourist shops and street stalls.

Roman-Era Magical 'Dead Nails' Protect the Living from the 'Restless Dead'?

A 2,000-year-old tomb discovered in Turkey was sprinkled with "dead nails" and sealed off with bricks and plaster, likely to "shield the living from the dead." Kristina Killgrove wrote in Live Science: The unusual grave, found at the site of Sagalassos in southwestern Turkey and dating to A.D. 100-150, had 41 bent and twisted nails scattered along the edges of its cremation pyre, 24 bricks that had been meticulously placed on the still-smoldering pyre, and a layer of lime plaster on top of that. The individual — an adult male — was cremated and buried in the same place, an unusual practice in Roman times, according to the study, published in February 21, 2023 in the journal Antiquity. [Source Kristina Killgrove, Live Science, March 14, 2023

"The burial was closed off with not one, not two, but three different ways that can be understood as attempts to shield the living from the dead — or the other way around," study first author Johan Claeys, an archaeologist at Catholic University Leuven (KU Leuven) in Belgium, told Live Science. Although each of these practices is known from Roman-era cemeteries — cremation in place, coverings of tiles or plaster, and the occasional bent nail — the combination of the three has not been seen before and implies a fear of the "restless dead," he said.

The archaeological site of Sagalassos was occupied from the fifth century B.C. to the 13th century A.D. and boasts numerous examples of Roman-era architecture, including a theater and a bath complex and the "non-normative cremation" described here. Typically, Roman-era cremations involved a funeral pyre followed by the collection of the cremains, which were put in an urn and then buried in a grave or placed in a mausoleum. The Sagalassos cremation, however, was performed in place, which the researchers could tell from the anatomical positioning of the remaining bones. Even more unusual was the contrast between the grave goods and the closure of the tomb. The archaeologists discovered typical funeral items — fragments of a woven basket, remains of food, a coin, and ceramic and glass vessels. "It seems clear that the deceased was buried with all appropriate aplomb," Claeys said. "It seems likely that was the suitable way of parting with a loved one at the time."

Claeys thinks that the man in this strange cremation grave was likely buried by his next of kin in a ceremony that would have taken days to prepare and carry out. The set of beliefs that encouraged people at Sagalassos to bury this man in an unconventional way are best understood as a form of magic, or an act intended to have specific effects because of a supernatural connection. It is possible that his odd burial was made to counteract an unusual or unnatural death; however, the researchers found no evidence of trauma or disease on the bones.

Business Insider reported: It was the only grave to use brick and lime out of about 180 or so burials that the archaeologists have uncovered. The nails were thought to "form a magical barrier surrounding the remains of the funeral pyre," the authors said in the study. Nails were expensive in Roman times, so they would likely not have been discarded by mistake, lead author on the study Johan Claeys, an archaeologist at Catholic University Leuven, told The Times. "They would have been valuable enough to be recovered if still serviceable. But they were dead nails, and the way they were distributed around the perimeter of the tomb suggests that the placement was purposeful," he said. [Source: Marianne Guenot, Business Insider, March 28, 2023]

Nails were often seen as imbued with magical properties, Matteo Borrini, a lecturer of forensic anthropology at the Liverpool John Moore University who was not involved in the study, told Insider. "The most common association with it is to fix something like pain," he said. The nails were also used to ask the deceased to carry a curse into the afterlife, he said. "In the Roman period, you write a curse against someone, you pinch with the nail, and then you fix this into the grave," he said. "That person that will become a sort of courier and will bring this letter to the eternal spirits who will start to chase and torment and torture the person in life," he said. The nails may also have been used to protect the body Though nails have been used for nefarious purposes elsewhere, in this particular instance they could also have been used to protect the body. In this burial site, there are signs to show that this person was respected at the time of their death, suggesting they wouldn't have been someone that people would have feared in life.

Roman-Era 'Death Magic' Used to Speak with the Dead

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Ancient human skulls, oil lamps and parts of weapons hidden in a cave near Jerusalem are signs the site was used in the Roman era for attempts to speak to the dead — a practice known as necromancy, or "death magic" — according to a new study. Based on the styles of the artifacts, the researchers think the morbid rituals were carried out at the Te'omim cave, about 20 miles (30 kilometers) west of Jerusalem, between the second and fourth centuries A.D According to Boaz Zissu, an archaeologist at Bar-Ilan University in Israel, most of the Jewish people who lived in the region had been eradicated or driven away by the ruling Roman Empire after the Jewish rebellion known as Bar Kokhba revolt, between A.D. 132 and 136. [Source Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, July 18, 2023]

The Romans then repopulated the region with people from other parts of their empire — likely from Syria, Anatolia and Egypt, Zissu said. "A new pagan population arrived in what had formerly been Judea, but was now Syria Palaestina," Zissu told Live Science. "They brought with them new ideas, new customs, and apparently the idea of necromancy." Zissu is an author, with archaeologist Eitan Klein of the Israel Antiquities Authority, in the study published July 4, 2023 in the journal published in the Harvard Theological Review. It describes the items discovered in the cave: more than 120 oil lamps, ax and spear blades, and three human craniums.

magic spell The styles of the oil lamps and some hidden coins suggest the cave became a place for necromancy when new arrivals to the area brought their traditional rituals with them, he said.

Necromancy was considered evil and often banned within the Roman Empire. Still, many ancient cities were near secret "oracle" sites where people believed they could speak to the dead. The cave became one such place. "There they found perfect conditions," Zissu said. "it's a bit remote, but not so far from the main road; it's deep, but not very deep; and it has a deep shaft at the end that they regarded as a connection to the underworld."

The lamps, human craniums and parts of weapons are lodged in crevices within the huge cave, often so far back that the researchers needed long poles with hooks on the end to retrieve them. Ancient people likely placed them there with poles, Zissu said. The crevices are too deep for the oil lamps to have cast much light, and researchers first thought they were artifacts of Chthonic worship — rituals associated with underworld spirits. But the craniums, also secreted in the crevices, suggested the real purpose was to try to speak to the dead, who were supposed to be able to foretell the future, Zissu said. Bones from individuals were sometimes used in an attempt to make contact with that person after their death, and the flickering of flames could be interpreted as their messages from the underworld, the study authors wrote.

Curses in Ancient Rome

Cicero described one lawyer who forgot what he was supposed to say during an argument and blamed "spells and curses" for his troubles. Personal problems and government failures were also blamed on curses. Worried that his sex life might be cursed, the 1st century poet Ovid wrote: “was I a wretched victim of charms and herbs, or did a witch curse my name upon a red wax image and stick the pins in the middle of the liver?”.

Recording what was found after the death of Germanicus, grandson of Augustus and heir of the Emperor Tiberius, in A.D. 19, the historian Tacitus wrote: “explorations of the floor and walls [of his house] brought to light the remains of human bodies, spells, curses, leaden tablets engraved with the name Germanicus, charred and blood-smeared vases, and others of the implements by which the living soul can be devoted to the powers of the grave." A woman named Martina was executed for murdering Germanicus and the Senator Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso and his wife Plancina, thought to have been behind the crime, were forced to commit suicide.

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The ancient Romans were a vindictive bunch. They regularly called on the gods to harm those they perceived had wronged them, sometimes recording their curses on thin lead tablets that were usually rolled up and deposited inside graves, temples, and shrines. While examining two such tablets recently rediscovered in the City Archaeological Museum of Bologna—their provenance is unknown—researcher Celia Sánchez Natalías of the University of Zaragoza in Spain found two particularly nasty examples. "Destroy, crush, kill, strangle Porcello and wife Maurilla. Their soul, heart, buttocks, liver..." says part of a tablet dating to the fourth or fifth century A.D. Sánchez Natalías believes this is a curse directed at a veterinarian and his wife, perhaps for the death of an animal. The second curse, one of the only known examples directed at a Roman senator, reads, "Crush, kill Fistus the senator.... May Fistus dilute, languish, sink, and may all his limbs be dissolved." One can only imagine what Fistus must have done to engender such vitriol. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology, Volume 65 Number 5, September/October 2012

Curse Tablets in Ancient Rome

The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, Persians, Jews, Christians, Gauls and Britons all dispensed curse tablets used to placate "unquiet" graves and call up the spirits of the underworld to make trouble. In the Roman Empire they were typically thin sheets that of lead that were buried, thrown into a well or pool, placed in a stone crack or nailed to the wall of a temple. They were typically addressed to infernal gods — like Pluto, Charon or Hecate — and often called for violent divine punishments in response for trivial slights, Dark said. [Source Tom Metcalfe Live Science, August 23, 2022]

In the Roman empire fortunetellers placed elaborate curses on lead tablets called defixiones . The practice was so common that scribes were hired to copy form-letter curses from "magical" papyri and many fortunetellers who dispensed curses made money from breaking them. Curse tablets endured until they were prohibited by the Christian Church. [Source: Christopher A. Faraone, Archaeology, March/April 2003]

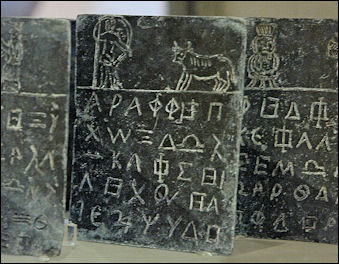

defixio Kardeelos Terme

Archaeologists have found hundreds of tablets with strange letters or the victim's name. The Greeks called them “curses that bind tight” and they appear to have invented them, with a great number focusing on sporting competitions or legal contests. The Latin term means “curses that fix or fasten someone.” “To make such a “binding spell," Christopher A. Faraone wrote in Archaeology magazine, “one would inscribe the victim's name and a formula on a lead tablet, fold it up, often pierce it with a nail, and then deposit it in a grave or a well or a fountain, placing it in the realm of ghosts or underworld divinities who might be asked to enforce the spell."

Curse tablets aimed at bringing misfortune to chariot racing teams have been found. One Roman-era curse tablet from Carthage read: "Bind the horses whose names and images on this implement I entrust you . . . Bind their running, their powers, their soul, their onrush, their speed. Take away their victory, entangle their feet, hinder them, hobble them, so that tomorrow morning in the hippodrome they are not able to run or walk about, or win, or go out of the starting gates, or advance either on the racecourse or track but they fall with their drivers." One aimed at a particular chariot team and driver that was buried with a rooster sacrifice went, “Just as this rooster has been bound by its feet, hands, and head, so bind the legs and hands and head and heart of Victoricus the charioteer of the Blue team, for tomorrow."

Curses were not always bad. Many were love spells. One from the A.D. fifth century read: "Grab Euphemia and lead her to me, Theon, loving me with frenzied love, and bind her with bonds that are unbreakable, strong and adamantine, so that she loves me, Theon, and do not allow her to eat, drink sleep or joke or laugh but make [her] rush out of every place and dwelling, abandon father, mother, brothers and sisters, until she comes to me, Theon, loving me, wanting me” with “unceasing and wild love. And if she holds someone else to her bosom, let her put him out, forget him, and hate him, but love, desire, and want me . . . Now, now. Quickly, quickly."

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: According to BBC News, more than one hundred curse tablets have been found in archaeological digs at the English city of Bath, which in Roman times was a resort famed for the healing powers of its hot springs. One tablet, featuring a curse for a stolen swimsuit, addressed the goddess of a temple there: "I give to your divinity and majesty [my] bathing tunic and cloak. Do not allow sleep or health to him who has done me wrong, whether man or woman or whether slave or free, unless he reveals themselves and brings those goods to your temple." [Source Tom Metcalfe Live Science, August 23, 2022]

Book: "Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World" by John Gager, professor or religion at Princeton (Oxford University Press, 1998)

Curse Directed at a Greengrocer

In 2011, researchers announced that they had deciphered a curse inscribed on two sides of a thin lead tablet tablet that called on Iao, the Greek name for Yahweh, god of the Old Testament, to strike down Babylas, a greengrocer selling fruits and vegetables in the city of Antioch in the A.D. 4th century. Written in Greek, the tablet with curse was dropped into a well in Antioch — part of southeast Turkey, near the border with Syria — when it was one of the Roman Empire's biggest cities in the East. The text was translated by Alexander Hollmann of the University of Washington. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, December 21, 2011 \=]

Roman-era voodoo doll

Owen Jarus of Live Science wrote: “The artifact, which is now in the Princeton University Art Museum, was discovered in the 1930s by an archaeological team but had not previously been fully translated. The translation is detailed in the most recent edition of the journal Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. "O thunder-and-lightning-hurling Iao, strike, bind, bind together Babylas the greengrocer," reads the beginning of one side of the curse tablet. "As you struck the chariot of Pharaoh, so strike his [Babylas'] offensiveness." \=\

“Hollmann told LiveScience that he has seen curses directed against gladiators and charioteers, among other occupations, but never a greengrocer. "There are other people who are named by occupation in some of the curse tablets, but I haven't come across a greengrocer before," he said. The person giving the curse isn't named, so scientists can only speculate as to what his motives were. "There are curses that relate to love affairs," Hollmann said. However, "this one doesn't have that kind of language." \=\

“It's possible the curse was the result of a business rivalry or dealing of some sort. "It's not a bad suggestion that it could be business related or trade related," said Hollmann, adding that the person doing the cursing could have been a greengrocer himself. If that's the case it would suggest that vegetable selling in the ancient world could be deeply competitive. "With any kind of tradesman they have their turf, they have their territory, they're susceptible to business rivalry.” \=\

“The name Babylas, used by a third-century Bishop of Antioch who was killed for his Christian beliefs, suggests the greengrocer may have been a Christian. "There is a very important Bishop of Antioch called Babylas who was one of the early martyrs," Hollmann said. The use of Old Testament biblical metaphors initially suggested to Hollmann the curse-writer was Jewish. After studying other ancient magical spells that use the metaphors, he realized that this may not be the case. "I don't think there's necessarily any connection with the Jewish community," he said. "Greek and Roman magic did incorporate Jewish texts sometimes without understanding them very well." \=\

“In addition to the use of Iao (Yahweh), and reference to the story of the Exodus, the curse tablet also mentions the story of Egypt's firstborn. “"O thunder—and-lightning-hurling Iao, as you cut down the firstborn of Egypt, cut down his [livestock?] as much as..." (The next part is lost.) "It could simply be that this [the Old Testament] is a powerful text, and magic likes to deal with powerful texts and powerful names," Hollmann said. "That's what makes magic work or make[s] people think it works." The lead curse tablet is very thin and could have been folded up.” \=\

Miracles in Ancient Rome

Marianne Bonz wrote for PBS’s Frontline: “In the first century of the common era, renowned men could also be credited with having performed miracles. The popular emperor Vespasian (A.D. 69-79) was credited with having performed several miracles. According to stories recorded by the Greek historians Dio Cassius and Tacitus, Vespasian worked several healing miracles, while visiting the shrine of Sarapis in Egypt. Among these miracles, Vespasian is credited with healing a blind man and restoring another man's crippled hand (Tacitus Histories 4.81). [Source: Marianne Bonz, Frontline, PBS, April 1998. Bonz was managing editor of Harvard Theological Review. She received a doctorate from Harvard Divinity School, with a dissertation on Luke-Acts as a literary challenge to the propaganda of imperial Rome.]

Ken Dark, an emeritus professor of archaeology and history at Reading University in the United Kingdom, told Live Science such "signs from God" and the later "miracles" were some of the few aspects of Roman superstition to survive the Roman Empire's transition to Christianity from the fourth century. "Christianity was dead against magic and that sort of thing, but people were prepared to accept that there could be signs that could foretell things," he said. An example was the Vision of Constantine, who, before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in A.D. 312, reportedly saw the Christian symbol of a cross in the sky and the words "In Hoc Signo Vinces" or "By this sign shall you conquer." The vision was reinforced by a dream a few days later, and Constantine ordered his troops to inscribe Christian symbols on their shields, won the decisive battle and thereafter converted from paganism to Christianity. [Source Tom Metcalfe Live Science, August 23, 2022]

Demi-Gods and Charlatans in Ancient Rome

Men like Apollonius of Tyana and Alexander of Abonoteichos acquired great celebrity as miracle workers, although the latter was a notorious charlatan. Marianne Bonz wrote for PBS’s Frontline: <iraculous powers were not limited to emperors, or even to people from the empire's social and political elite. Miracles were a sign of a special relationship between the gods and particular individuals. People who were thought to possess great wisdom or virtue were also frequently credited with performing miracles. One interesting example of a wonder-working, itinerant philosopher is that of Apollonius of Tyana. Apollonius was a late first-century follower of the famous Greek philosopher, Pythagoras, whom some believed had become a god. Having renounced his possessions and worldly position in virtuous pursuit of divine wisdom, Apollonius was reputed to have led a disciplined and rigorously ascetic life.

“According to his later biographer, Philostratus, Apollonius possessed extraordinary gifts, including innate knowledge of all languages, the ability to foretell the future, and the ability to see across great distances. Apollonius's possession of divine wisdom also endowed him with the ability to heal the sick and demon-possessed, and Philostratus narrates the miraculous quality of a number of these cures and exorcisms. What all of these stories of wonder workers have in common is that (in contrast to magic, which is performed by charlatans for personal profit) miracles are performed by exceptional human beings, in the service of a god, for the good of other people.

“In addition to mere human beings, who were so favored either because of their extraordinary power or their extraordinary wisdom and virtue, the world of the early Roman empire was also inhabited by another group of individuals who could serve as intermediaries between the gods above and the world below. These were the demi-gods or heroes, individuals of mixed parentage (human and divine). They were usually credited with possessing extraordinary powers, while also possessing great understanding of and compassion for the pain and suffering of ordinary human beings.

“In general, their demi-god status is expressed in the fact that they live as mortals; but when they die, they retain their fully vigorous human appearance, as well as their former powers. Because of their unique status and qualities, in the popular imagination these demi-gods were frequently regarded as protectors. In the world of the first century, Herakles (Hercules) and Asclepius were two of the most widely worshipped of these protector or "savior" gods.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024