Home | Category: Religion and Gods

VESTAL VIRGINS

Six Vestal Virgins tended the shrine for the household goddess Vesta at the Vesta Temple in Rome and watched the eternal flame of Rome there, which burned for more than a thousand years. They were ordained at the age of seven and lived in pampered but secluded luxury.

Each Vestal had to serve thirty years. Any vacancy in the Order was filled promptly by the appointment of a girl of suitable family, not less than six years old nor more than ten, physically perfect, of unblemished character, and with both parents living. Ten years were spent by the Vestals in learning their duties, ten in performing those duties, and ten in training the younger Vestals. In addition to the care of the fire the Vestals had a part in most of the festivals of the old calendar. They lived in the Atrium Vestae beside the temple of Vesta in the Forum. At the end of her service a Vesta; might return to private life, but such were the privileges and the dignity of the Order that this rarely occurred. A Vestal was freed from her father’s potestas.” [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932)]

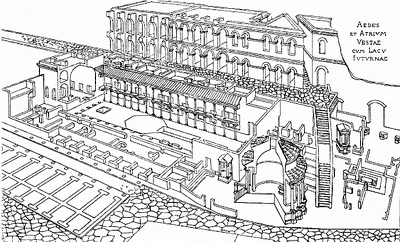

Elda Biggi wrote in National Geographic History: Unlike most Roman religious cults, worship of Vesta was run by women. The hearth was sacred to this goddess, one of Rome’s three major virgin goddesses (the other two being Minerva and Diana). The rites surrounding the Vestals remained relatively fixed from the time of the Roman Republic through the fourth century A.D. Six virgin priestesses were dedicated to Vesta as full-time officiates who lived in their own residence, the Atrium Vestae in the Roman Forum. The Vestals’ long tradition gave Romans a reassuring thread of continuity and may explain the Temple of Vesta’s traditional circular form, a style associated with rustic huts in the city’s deep past. [Source Elda Biggi, National Geographic History, December 18, 2018]

According to legend, Romulus and Remus' mother Rhea served as a Vestal Virgin before her death. Their most important duty was watching over the flame of Vesta — a fire burning in a temple located in the city. The flame symbolized not only the goddess Vesta, but also the status of Rome itself. If the fire were to ever go out, Romans viewed it as a sign that the city could be in danger. When the flames did go out, which perhaps happened accidentally. When this happened, it is said, the Vestal Virgins were punished harshly — sometimes by being buried alive. [Source: BuzzFeed, September 20, 2023]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Rome's Vestal Virgins” by Robin Lorsch Wildfang (2006) Amazon.com;

“Vestal Virgins, Sibyls, and Matrons: Women in Roman Religion”

by Sarolta A. Takács (2022) Amazon.com;

“Portraits of the Vestal Virgins, Priestesses of Ancient Rome” by Molly Lindner (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Temple And Altar Of Vesta” by T Cato Worsfold (1861-1936) Amazon.com;

“The History of the Vestel Virgins of Rome” by Sir T. Cato. Worsfold (1934), Currently unavailable. Amazon.com;

“Demeter, Isis, Vesta, and Cybele: Studies in Greek and Roman Religion in Honour of Giulia Sfameni Gasparro” by Attilio Mastrocinque, Concetta Giuffre Scibona (2012) Amazon.com;

“A Place at the Altar: Priestesses in Republican Rome” by Meghan J. DiLuzio Amazon.com;

“I, Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome” by E. E. Kleiner (1996) Amazon.com;

“Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity” by Sarah Pomeroy (1995) Amazon.com;

“Women's Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation” by Maureen B. Fant and Mary R. Lefkowitz (2016) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Greece and Rome” (Cambridge Educational) by Michael Massey (1988) Amazon.com;

“The Architecture of Roman Temples: The Republic to the Middle Empire”

by John W. Stamper Amazon.com;

“Temples, Religion and Politics in the Roman Republic” by Eric M. Orlin (1996) Amazon.com;

“Religions of Rome: Volume 1: A History” by Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price ( Amazon.com;

“Religions of Rome: Volume 2: A Sourcebook” by Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price ( Amazon.com;

“The Dancing Lares and the Serpent in the Garden: Religion at the Roman Street Corner” by Harriet I. Flower (2017) Amazon.com;

"Archaic Roman Religion, Volume 1 Paperback by Georges Dumézil, Philip Krapp (1996) Amazon.com;

“Archaic Roman Religion, Volume 2" by Georges Dumézil (1996) Amazon.com;

"Roman Myths: Gods, Heroes, Villains and Legends of Ancient Rome” by Martin J Dougherty (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“Household Gods: Private Devotion in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Alexandra Sofroniew (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Religion of the Etruscans” by Nancy Thomson de Grummond, Erika Simon (2006) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Animal Sacrifice: Ancient Victims, Modern Observers”

by Christopher A. Faraone and F. S. Naiden (2012) Amazon.com;

“Magic and Religion in the Ancient Mediterranean World” by Radcliffe G. Edmonds III and Carolina López-Ruiz (2023) Amazon.com

Temple of Vesta — Where the Vestal Virgins Lived and Worked

The ruins of the Atrium Vestae stand in the Roman Forum. This place of worship, the Temple of Vesta, which lay alongside the Atrium. Here, the priestesses tended the goddess’s sacred fire. The rectangular pools formed a part of the complex’s long, central patio. The remains of the Temple of Vesta are in front of a the wall with the three remaining columns of the Temple of Castor and Pollux. [Source Elda Biggi, National Geographic History, December 18, 2018]

The Upper Forum in Rome (Colosseum-side entrance of the Forum) contains the House of Vestal Virgins, The Temple of Vesta the Temple of Antonius and Fustina (near the Basilica of Maxentius). The House of Vestal Virgins (near Palantine Hill, next to the Temple of Castor and Pollex) is a sprawling 55-room complex with statues of virgin priestess. The statue whose name has been scratched is believed to belong to a virgin who converted to Christianity. The Temple of Vesta (Temple of the Vestal Virgins) is a restored circular buildings where vestal virgins performed rituals and tended Rome's eternal flame for more than a thousand years. Across the square from the temple is the Regia, where Rome's highest priest had his office.

The Vesta organization was one of the oldest and most famous colleges in Rome. The Regia on the Forum Romanum formed one of the centers of Vestal Virgin cult activities. It is believed to have been part of a complex that embraced the atrium and aedes Vestae as well. The sacred fire was on upon the altar of the Aedes Vestae.There was no statue of the goddess in the temple. The temple itself was round and had a pointed roof, and even in its latest development of marble and bronze had not gone far in shape and size from the round hut of poles and clay and thatch in which village girls had tended the fire whose maintenance was necessary for the primitive community. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932)]

History of the Vestal Virgins

Elda Biggi wrote in National Geographic History: According to Roman authors, the cult was founded by Numa Pompilius, a semi-mythical Roman king who ruled around 715 to 673 B.C. Numa was the successor of Rome’s founder, Romulus. First-century A.D. historian Plutarch wrote that Numa may have “considered the nature of fire to be pure and uncorrupted and so entrusted it to uncontaminated and undefiled bodies.“ Numa is credited by Livy, in his History of Rome, with formalizing other key Roman cults, including those of Jupiter and Mars. Many historians believe Numa was legendary, and that the worship of Vesta and other cults developed slowly out of pre-Roman customs, perhaps dating back to the older Etruscan culture that dominated Italy before the rise of Rome. [Source Elda Biggi, National Geographic History, December 18, 2018]

In the innermost part of their temple, the priestesses looked after their secret talismans. Among these objects was the sacred phallus, the fascinus, the representation of a minor god of the same name. The fascinus (the root of the word “fascinate”) is closely bound with magic and fertility. It was also in this part of the temple that they probably kept the palladium, the statue of Pallas Athena that the legendary founder of Rome, Aeneas, brought to Italy after the destruction of Troy, his home city—another aspect of the Vestal cult that tied Rome’s origins into an ennobling and ancient tradition.

Romans regarded these priestesses with a sense of awe. Plutarch points out “they were also keepers of other divine secrets, concealed from all but themselves.” It was believed they possessed magical powers: If anybody condemned to death saw a Vestal on his way to being executed, he was to be freed, so long as it could be proven the meeting was not by design. Vestals, it was said, could stop a runaway slave in his tracks.

The privileged position of the Vestal Virgins in Roman society survived for more than a thousand years, passing through Rome’s changing systems of monarchy, republic, and empire. The cult would not, however, survive Christianity. In A.D. 394 Theodosius closed the House of the Vestals forever, freeing the virgins from their obligations, but also removing their privileges.

Even as their flame was extinguished, aspects of the cult may have passed into the new faith as it swept through the Mediterranean. Just as the position of the Pontifex Maximus lived on in the papal title “pontiff,” young women in the early years of Roman Christianity embraced virginity and celibacy in their desire to be “eunuchs for the love of heaven.” Scholars believe the role of the Christian nun was inspired, in part, by the chaste figures who dutifully tended the holy flame of Vesta.

Duties of the Vestal Virgins

Once a year, in March, they Vestal Virgins relit the fire and then ensured it remained burning for the next year. According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: Under the direction of a virgo maxima, their essential mission was to maintain the public hearth in the aedes Vestae. Their liturgical importance is confirmed by two significant points. Once a year, they would make their way to the king in order to ask him: "Are you vigilant, king? Be vigilant!" On another solemn occasion, the virgo maxima mounted the Capitolium in the company of the pontifex maximus (Horace, Carmina 3.30.8).[Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

Elda Biggi wrote in National Geographic History: Daily rites for Vestals were often centered around the temple. Most important was maintaining the holy fire. If the fire went out, the attending Vestals would be suspected not only of neglect but also of licentiousness, since it was believed impurity in a Vestal’s relations would cause a fire to go out. Other typical duties included the purification of the temple with water, which had to be drawn from a running stream. In readiness for the numerous festivals that required their attendance, the priestesses were required to bake salsa mola, a cake of meal and salt that was sprinkled on the horns of sacrificed animals. Important religious festivals included the Vestalia, dedicated to their goddess, Vesta, and the Lupercalia, which highlights the contradictory role of the Vestal Virgins, as it was closely associated with fertility. [Source Elda Biggi, National Geographic History, December 18, 2018]

The tasks of lighting and maintaining the fire were serious endeavors as the fire was tied to the fortunes and well-being of Rime, and neglect could bring ruin. To light a fire in Roman times could be a toilsome task of rubbing wood on wood, or later striking flint on steel to get the precious spark. But the modern invention of flint and steel was never used to rekindle the sacred fire. Ritual demanded the use of friction. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932)]

Selection of the Vestal Virgins

Elda Biggi wrote in National Geographic History: To become a Vestal was the luck of the draw. Captio, the process whereby the girls were selected to leave their families and become priestesses, is also the Latin word for “capture”—a telling turn of phrase that evokes the kidnapping of women for brides that took place in archaic Rome. [Source Elda Biggi, National Geographic History, December 18, 2018]

Records from 65 B.C. show that a list of potential Vestals was drawn up by the Pontifex Maximus, Rome’s supreme religious authority. Candidates had to be girls between the ages of six and 10, born to patrician parents, and free from mental and physical defects. Final candidates were then publicly selected by lot. Once initiated, they were sworn to Vesta’s service for 30 years.

On being selected, their life was spent at the Atrium Vestae in a surrogate family, presided over by older Vestals. In addition to room and board, they were entitled to their own bodyguard of lictors. For the first 10 years they were initiates, taught by the older priestesses. Then they became priestesses for a decade before taking on the mentoring duties of the initiates for the last 10 years of their service.

Training and Clothes of the Vestal Virgins

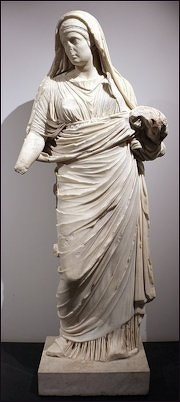

statue of a vestal virgin

Elda Biggi wrote in National Geographic History: After lots were drawn from the list of young girls who could serve Vesta, initiates were brought to the Atrium Vestae, where their training would begin. The training was overseen by the chief priestess, the Vestalis Maxima, who came under the authority of the Pontifex Maximus. The first 10 years were spent training for their duties. [Source Elda Biggi, National Geographic History, December 18, 2018]

They would spend the second decade actively administering rites, and the final 10 were spent training novices. The chastity of the priestesses was a reflection of the health of Rome itself. Although spilling a virgin’s blood to kill her was a sin, this did not preclude the infliction of harsh corporal punishment. First-century historian Plutarch writes: “If these Vestals commit any minor fault, they are punishable by the high-priest only, who scourges the offender.”

Public monies and donations to the order funded the cult and the priestesses. In Rome religion and government were tightly intertwined. The organization of the state closely mirrored that of the basic Roman institution: the family. The center of life of the Roman home, or domus, was the hearth, tended by the matriarch for the good of her family and husband. In the same way, the Vestals tended Vesta’s flame for the good of the state.

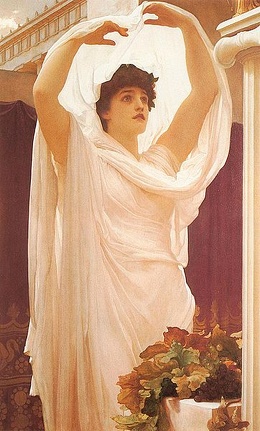

The ceremonial dress of Vestals highlights their dual, and somewhat contradictory, embodiment of both the maternal and the chaste. Physical appearance was an integral part of their role, making them stand out as different from other women, but also echoing physical traits of conventional women. Dressed in white, the color of purity, the Vestal Virgins wore stola, long gowns worn by Roman matrons. Hair and headdresses played an important symbolic function. The Vestal hairstyle is described in Roman sources using an ancient Latin phrase, the seni crines. Historians cautiously agree it means “sixbraids,” and is mentioned as the coiffure of both Vestal Virgins and brides. A Vestal wore the suffibulum, a short, white cloth similar to a bride’s veil, kept in place with a brooch, the fibula. Around their heads they wore a headband, the infula, which was associated with Roman matrons.

Privileges of the Vestal Virgins

As long as they remained pure, vestal virgins were among the most respected women in Rome. They could walk unaccompanied and had the power to pardon prisoners. Under Augustus they were rewarded with the best seats at gladiator contests, exclusive parties and feasts with sow's bladder and thrushes.

Unlike many other Roman women, Vestal virgins could own property and enjoyed certain tax exemptions. They were free from their family’s patria potestas, patriarchal power. They could make their own wills and give evidence in a court of law without being obligated to swear an oath. [Source Elda Biggi, National Geographic History, December 18, 2018]

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Being a Vestal Virgin was considered a great honor, and it's said that families boasted if one of their relatives had become one. They had several assistants, including personal hairdressers for each priestess who maintained their hair in a unique formal style with braids and ribbons that took several hours to achieve. Plutarch said that Vestal Virgins who had maintained their chastity for 30 years could retire on a pension and were allowed to marry; many Romans believed marrying a former Vestal Virgin would bring luck and prosperity, and some men divorced their wives to do so. [Source Tom Metcalfe Live Science, August 23, 2022]

Sacrifices and Punishments of the Vestal Virgins

Elda Biggi wrote in National Geographic History: The rights of vestal virgins came at a high price: 30 years of enforced chastity. Many historians believe that the health of the state was tied to the virtue of its women; because the Vestals’ purity was both highly visible and holy, penalties for a Vestal breaking her vow of chastity were draconian. As it was forbidden to shed a Vestal Virgin’s blood, the method of execution was immuration: being bricked up in a chamber and left to starve to death. Punishment for her sexual partner was just as brutal: death by whipping. Throughout Roman history, instances are cited of these grim sentences being passed. [Source Elda Biggi, National Geographic History, December 18, 2018]

It is said, that if the Vestal Virgins lost their virginity they were buried alive with a burning candle and bread so they could stay alive long enough to contemplate their sins. They could also be blamed for misfortune or letting the vestal fires go out. Disasters in the Roman state happened surprisingly often. Being buried alive was not considered humane. to get around this, Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science, the Romans devised the solution of lowering a condemned Vestal Virgin into an underground room with enough food to last them a few days and then walling them up; eventually, they would starve to death, and it was held that the starving, not being buried alive, had killed them.[Source Tom Metcalfe Live Science, August 23, 2022]

Vestal Virgin Accused of Losing Their Virginity

Elda Biggi wrote in National Geographic History: Jealousy or malice made the Vestal Virgins vulnerable to false accusations. One story, celebrated by several Roman writers, concerns the miracle of the Vestal Virgin Tuccia, who was falsely accused of being unchaste. According to tradition, Tuccia beseeched Vesta for help and miraculously proved her innocence by carrying a sieve full of water from the Tiber.[Source Elda Biggi, National Geographic History, December 18, 2018]

Allegations of crimes against the Vestals’ chastity sometimes went to the top of the social order. Nero perssonally invited the Vestals to the public games but was also accused or raping one. The flamboyantly eccentric, third-century emperor Elagabalus actually married a serving Vestal Virgin. It is a sign of the enduring symbolic importance of the cult that this heresy was one major factor that led to his deposal and murder.

Marcus Licinius Crassus was one of the richest and most powerful Roman citizens in the first century B.C. Yet he nearly lost it all, his life included, when he was accused of being too intimate with Licinia, a Vestal Virgin. He was brought to trial, where his true motives emerged. As the first-century historian Plutarch recounts, Licinia was the owner of “a pleasant villa in the suburbs which Crassus wished to get at a low price, and it was for this reason that he was forever hovering about the woman and paying his court to her.” When it became clear that Crassus’ wooing was motivated by avarice rather than lust, he was acquitted, saving both his and Licinia’s lives. One of the most remarkable elements of this story is the fact that Licinia owned a villa in the first place. Unlike other women, Licinia could own property precisely because she was a Vestal Virgin. The story of her trial also reveals how that privilege came with a price.

Plutarch on the Vestal Virgins

Plutarch wrote in “Life of Numa,” xi-xiv: The chief priest “was also guardian of the vestal virgins, the institution of whom, and of their perpetual fire, was attributed to Numa, who, perhaps, fancied the charge of pure and uncorrupted flames would be fitly entrusted to chaste and unpolluted persons, or that fire, which consumes but produces nothing, bears an analogy to the virgin estate. Some are of opinion that these vestals had no other business than the preservation of this fire; but others conceive that they were keepers of other divine secrets, concealed from all but themselves. Gegania and Verenia, it is recorded, were the names of the first two virgins consecrated and ordained by Numa; Canuleia and Tarpeia succeeded; Servius Tullius afterwards added two, and the number of four has been continued to the present time. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127) “Lives”, written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden]

“The statutes prescribed by Numa for the vestals were these: that they should take a vow of virginity for the space of thirty years, the first ten of which they were to spend in learning their duties, the second ten in performing them, and the remaining ten in teaching and instructing others. Thus the whole term being completed, it was lawful for them to marry, and leaving the sacred order, to choose any condition of life that pleased them. But, of this permission, few, as they say, made use; and in cases where they did so, it was observed that their change was not a happy one, but accompanied ever after with regret and melancholy; so that the greater number, from religious fears and scruples forbore, and continued to old age and death in the strict observance of a single life.

“For this condition he compensated by great privileges and prerogatives; as that they had power to make a will in the lifetime of their father; that they had a free administration of their own affairs without guardian or tutor, which was the privilege of women who were the mothers of three children; when they go abroad, they have the fasces carried before them; and if in their walks they chance to meet a criminal on his way to execution, it saves his life, upon oath being made that the meeting was accidental, and not concerted or of set purpose. Any one who presses upon the chair on which they are carried is put to death.

“If these vestals commit any minor fault, they are punishable by the Pontifex Maximus only, who scourges the offender, sometimes with her clothes off, in a dark place, with a curtain drawn between; but she that has broken her vow is buried alive near the gate called Collina, where a little mound of earth stands inside the city reaching some little distance, called in Latin agger; under it a narrow room is constructed, to which a descent is made by stairs; here they prepare a bed, and light a lamp, and leave a small quantity of victuals, such as bread, water, a pail of milk, and some oil; that so that body which had been consecrated and devoted to the most sacred service of religion might not be said to perish by such a death as famine. The culprit herself is put in a litter, which they cover over, and tie her down with cords on it, so that nothing she utters may be heard. They then take her to the forum; all people silently go out of the way as she passes, and such as follow accompany the bier with solemn and speechless sorrow; and, indeed, there is not any spectacle more appalling, nor any day observed by the city with greater appearance of gloom and sadness. When they come to the place of execution, the officers loose the cords, and then the Pontifex Maximus, lifting his hands to heaven, pronounces certain prayers to himself before the act; then he brings out the prisoner, being still covered, and placing her upon the steps that lead down to the cell, turns away his face with the rest of the priests; the stairs are drawn up after she has gone down, and a quantity of earth is heaped up over the entrance to the cell, so as to prevent it from being distinguished from the rest of the mound. This is the punishment of those who break their vow of virginity.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024