Home | Category: Religion and Gods

STATE RELIGION IN ANCIENT ROME

Caesar's deification In the wake of the Republic's collapse, state religion had adapted to support the new regime of the emperors. Augustus, the first Roman emperor, justified the novelty of one-man rule with a vast program of religious revivalism and reform. Public vows formerly made for the security of the republic now were directed at the well-being of the emperor. So-called "emperor worship" expanded on a grand scale the traditional Roman veneration of the ancestral dead and of the Genius, the divine tutelary of every individual. The Imperial cult became one of the major ways in which Rome advertised its presence in the provinces and cultivated shared cultural identity and loyalty throughout the Empire. Rejection of the state religion was tantamount to treason. This was the context for Rome's conflict with Christianity, which Romans variously regarded as a form of atheism and novel superstitio. Ultimately, Roman polytheism was brought to an end with the adoption of Christianity as the official religion of the empire. [Source: Wikipedia]

The origins of state religion can be found in federal cults who origins go back to the time when Rome first evolved. One federal cult would play an important role in history because it held privileged ties with the Romans. This cult was centered at Lavinium, in the port city of Latium, six kilometers (3.7 miles) to the south of Rome. Excavations at site have revealed a necropolis dating back to the tenth century B.C. According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: There are also ruins of ramparts dating from the sixth century, the vestiges of a house of worship flanked by thirteen altars, and a mausoleum that houses an archaic tomb from the seventh century B.C. Thousands of votives attest the appeal of a healing sanctuary for several centuries. In the imperial period, the religious existence of the city was preserved in the form of a symbolic community, whose offices were assigned like priesthoods to members of the Roman equestrian class. [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

The integration of federal cults into Roman dominance could follow different routes. The Romans' capacity for adaptation to different circumstances is evident here in an especially remarkable way. One of the most ancient federal cults presupposes the original preeminence of the ancient city of Alba Longa: the Feriae Latinae (Latin holidays) were celebrated at the summit of the Alban Hills in honor of Jupiter Latiaris. In earlier times, the Latins had been granted an equal share of the sacrifice, which consisted of a white bull. Once the consecrated entrails (exta) were offered to the god, all in attendance would share the meat, thus demonstrating their bonds of community.

After the destruction of Alba Longa, Rome quite naturally picked up the thread of this tradition by incorporating the Feriae Latinae as a movable feast into its liturgical calendar. Still, the attitude of the Romans was selective: even though they transferred the entire Alban population to Rome itself, they kept the Alban celebrations in their usual locations. They simply built a temple to Jupiter Latiaris where previously there was only a lucus, a sacred grove. During the historical epoch, the Roman consuls, accompanied by representatives of the state, would make their way to the federal sanctuary shortly after assuming their responsibilities and would preside there over the ceremonies. The Feriae Latinae had come under Roman control.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Rituals and Power: The Roman Imperial Cult in Asia Minor” (Reprint Edition)

by S. R. F. Price (1954-2011) Amazon.com;

“Emperor Worship and Roman Religion” (Oxford Classical Monographs)

by Ittai Gradel (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Imperial Cult: Emperor Anastasius I: A Practical Manual for the Worship of the Divine Emperor” by Marcus Julianus Amazon.com;

“Roman Emperor Worship” by Louis Matthews Sweet (1919) Amazon.com;

“Religions of Rome: Volume 1: A History” by Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price ( Amazon.com;

“Religions of Rome: Volume 2: A Sourcebook” by Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price ( Amazon.com;

“The Dancing Lares and the Serpent in the Garden: Religion at the Roman Street Corner” by Harriet I. Flower (2017) Amazon.com;

"Archaic Roman Religion, Volume 1 Paperback by Georges Dumézil, Philip Krapp (1996) Amazon.com;

“Archaic Roman Religion, Volume 2" by Georges Dumézil (1996) Amazon.com;

"Roman Myths: Gods, Heroes, Villains and Legends of Ancient Rome” by Martin J Dougherty (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“Household Gods: Private Devotion in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Alexandra Sofroniew (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Religion of the Etruscans” by Nancy Thomson de Grummond, Erika Simon (2006) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Animal Sacrifice: Ancient Victims, Modern Observers”

by Christopher A. Faraone and F. S. Naiden (2012) Amazon.com;

“Magic and Religion in the Ancient Mediterranean World” by Radcliffe G. Edmonds III and Carolina López-Ruiz (2023) Amazon.com

Early State Religion in Ancient Rome

According to Roman tradition King Numa established the Roman calendar with its cycle of feasts and its listing of days on which public business could or could not be conducted (dies fasti et nefasti ). According to Encyclopedia.com: The king himself was chief priest. He was assisted primarily by two collegiate priesthoods, the College of Pontiffs, and the College of Augurs. After the establishment of the Republic (c. 509 B.C.), the two colleges mentioned became the two most important religious bodies in the state. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

Column of Antoninus Pius

The chief pontiff, the Pontifex Maximus, was the head of the state religion, with supervisory control over religion in general. A rex sacrorum continued, to some extent, the religious functions of the Roman kings. In the absence of a priestly caste, Roman magistrates served in these colleges and performed the priestly functions. The College of Pontiffs kept the calendar and were the guardians and interpreters of ius divinum and ius humanum, retaining a monopoly over the legis actiones or forms of pleading until the late 4th century B.C. The main business of the pontiffs was to maintain the pax deorum, the proper relations between the divine powers and the state. The College of Augurs, by observing the flights of birds and other phenomena, indicated whether the omens were favorable or unfavorable regarding a public action to be taken. In matters of grave concern the Romans made use of the Etrusca disciplina, or hepatoscopy. A priesthood, the flamines, performed certain rites in honor of Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus; the Salian brotherhood were devoted to the worship of Mars; and the vestal virgins spent the greater period of their lives in the cult of Vesta as symbolized in the sacred hearth fire of the state. A special college of priests, the Fetiales, carried out magico-religious ceremonies connected with the declaration of war. The Roman triumph after victory was a solemn religious act of thanksgiving.

The Romans honored their divinities with sacrifices of animals, first fruits, libations, and prayers. The animals sacrificed were chiefly pigs, but sheep and oxen also were immolated. Every five years a solemn lustratio or purification of the city was held, consisting of a procession, sacrifices, and prayers. Of the early Roman temples, that erected to Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitol was the most important. It should be noted also that the ludi, or public games of the Romans, were religious in origin and long maintained their religious character. The religious rites of the state had to be carried out with scrupulous exactness. They inculcated a spirit of discipline and order, but they had little emotional appeal.

Imperial Cult in Ancient Rome

Dr Neil Faulkner wrote for the BBC: “This concept, of a tough but essentially benevolent imperial power, was embodied in the person of the emperor. His presence was felt everywhere. His statues dominated public places. He was worshipped alongside Jupiter and the military standards in frontier forts, and in the sanctuaries of the imperial cult in provincial towns. His image was stamped on every coin, and thus reached the most remote corners of his domain - for there is hardly a Roman site, however rude, where archaeologists do not find coins. The message was clear: thanks to the leadership of the emperor we can all go safely about our business and prosper. [Source: Dr Neil Faulkner, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

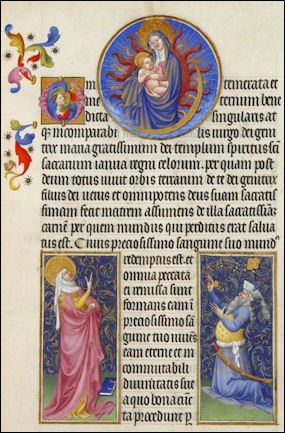

The Virgin the Sibyl

and the Emperor Augustus“How did the spin-doctors of ancient Rome represent the great leader to his people? Sometimes, wearing cuirass and a face of grim determination, he was depicted as a warrior and a general; an intimidating implicit reference to global conquest and military dictatorship. At other times, he wore the toga of a Roman gentleman, as if being seen in the law-courts, making sacrifice at the temple, or receiving guests at a grand dinner party at home. In this guise, he was the paternalistic 'father of his country', the benevolent statesman, the great protector. |::|

Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “The cult of the emperors developed naturally enough from the time of the deification of Julius Caesar. The movement for this deification was of Oriental origin. The Genius of the emperor was worshiped as the Genius of the father had been worshiped in the household. The cult, beginning in the East, was then established in the western provinces and finally in Italy. It was under the care of the seviri Augustales in the municipalities. The worship of the emperor in his lifetime was not permitted at Rome, but spread through the provinces, taking the place of the old state religion. It was this that caused the opposition to Christianity, for the refusal of the Christians to take part was treasonable. Their offense was political, not religious. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

A sculpted relief from the base of the column of the emperor Antoninus Pius, dated to A.D. 161, shows the apotheosis (transformation into gods) of Antoninus Pius and his wife Faustina. “They are shown by the portrait busts at the top of the frame, flanked by eagles - associated with imperial power and Jupiter - and were typically released during imperial funerals to represent the spirits of the deceased. Antoninus and Faustina are being carried into the heavens by a winged, heroically nude figure. The armoured female figure on the right is the goddess Roma, a divine personification of Rome, and the reclining figure to the left - with the obelisk - is probably a personification of the Field of Mars in Rome, where imperial funerals took place. [Source: BBC]

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: The imperial cult was not universally accepted and liked. Seneca ridiculed the cult of Claudius, and Tacitus spoke of the cult in general as Greek adulation. In the third century the historian Dio Cassius attributed to Augustus's friend Maecenas a total condemnation of the imperial cult. Jews and Christians objected to it on principle, and the acts of the Christian martyrs remind us that there was an element of brutal imposition in the imperial cult. But its controversial nature in certain circles may well have been another factor in the cult's success (conflicts help any cause). There is even evidence that some groups treated the imperial cult as a mystery religion in which priests displayed imperial images or symbols. [Source: Arnaldo Momigliano (1987), Simon Price (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

Emperor Worship in Ancient Rome

Emperor worship was a key part of Rome state religion. Generally referred to as the imperial cult, it regarded emperors and members of their families as gods. Starting with Caesar and Augustus emperors that considered themselves gods ruled the Roman Empire. The Roman emperors seemed to believe in their divinity and they demanded that their subjects worship them. Marcellus was honored with a festival. Flaminius was made a priest for three hundred years. Ephesus had a shrine for Serilius Isauricus. Antony and Cleopatra referred to themselves as Dionysus and Osiris and named their children Sun and Moon. Caligula and Nero demanded to be worshiped like gods in their lifetime. And Vespasian said on his deathbed "Oh dear, I'm afraid I'm becoming a God."

Dr Nigel Pollard of Swansea University wrote for the BBC: “On his death, Julius Caesar was officially recognised as a god, the Divine ('Divus') Julius, by the Roman state. And in 29 B.C. Caesar's adopted son, the first Roman emperor Augustus, allowed the culturally Greek cities of Asia Minor to set up temples to him. This was really the first manifestation of Roman emperor-worship. [Source: Dr Nigel Pollard of Swansea University, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|]

“While worship of a living emperor was culturally acceptable in some parts of the empire, in Rome itself and in Italy it was not. There an emperor was usually declared a 'divus' only on his death, and was subsequently worshipped (especially on anniversaries, like that of his accession) with sacrifice like any other gods. |::|

See Separate Article: ROMAN EMPEROR WORSHIP europe.factsanddetails.com

Politics and Religion in Ancient Rome

Mary Beard wrote in The New Yorker: That axiom helps explain why Augustus, when he compiled a list of his achievements — a summary of his greatest hits — to be displayed outside his mausoleum, included the fact that he had restored eighty-two temples in the city. Civil war had torn Rome apart for a century before he came to power; with these temple restorations, he could now be seen as literally repairing Rome’s relations with the gods. It was also one of the reasons that Elagabalus must have seemed a threat. In addition to his reported excesses and cruelty, he was rumored to have plans to replace Jupiter as the chief deity of the state with a Syrian god. How could Rome survive if it simply threw over the gods who had insured its success? One can recognize a similar logic behind the persecution — or “punishment,” to give it a Roman spin — of the Christians throughout the first two centuries A.D. There must have been a lurking fear among the authorities that the wholesale Christian rejection of the traditional gods would put the state in peril. [Source: Mary Beard, The New Yorker, July 3, 2023]

The connection between politics and religion was so ingrained in Roman life that the people who controlled the state also controlled its religious rites. The one notable exception was the Vestal Virgins — the priestesses charged with keeping alight the sacred flame of the goddess Vesta in the Forum, while also remaining virgins under penalty of death. (Of course, ancient gossips spread all kinds of rumors.) Otherwise, the major groups or “colleges” of priests in Rome were made up of senators. They had their own particular responsibilities — interpreting signs sent from the gods, say, or worshipping individual deities. But these priests were not exclusively religious practitioners, and they had no pastoral responsibilities for any congregation. Romans did not go to them for personal advice or spiritual counselling.

As a member of all the priestly colleges, the emperor was effectively the head of Roman religion as well as its chief priest. That is how we often still see emperors depicted in sculpture, conducting a sacrifice or displaying their piety in various other ways. Alongside the governors’ reports and pleading letters from subjects, the regular contents of an emperor’s in-tray would have included requests for permission to move someone’s great-uncle’s coffin according to the terms of divine law, or to fill a vacancy in one of the priestly groups. It was through the emperor, more than anyone else, that human relations with the gods were correctly maintained. And some emperors moved relatively seamlessly, in death, from being intermediaries to being gods themselves.

Imperial Cult Worship in the Roman Empire

Mary Beard wrote in The New Yorker: All the same, certain emperors and their family members clearly were treated as immortal gods, with worship continuing for decades, sometimes even centuries, after their deaths. The temples of divus Julius (Caesar), divus Vespasian, and divus Antoninus (Pius) and his wife, diva Faustina, still dominate the Roman Forum. Even Claudius — despite the ending of Seneca’s satiric fantasy — had his own prominent temple in Rome. Inscribed records give us the names of numerous priests of divine emperors while also listing occasions for the sacrifice of an animal. On divus Augustus’ birthday, September 23rd, for example, an ox would be slaughtered in his honor, while, on his wife’s birthday, a cow would be slaughtered for her. [Source: Mary Beard, The New Yorker, July 3, 2023]

These forms of worship could be found outside Rome, too. A surviving papyrus calendar, from the two-twenties A.D., gives us a window into the religious practices of a Roman Army unit stationed at the base of Dura Europos, on the River Euphrates, in what is now Syria. Discovered in the nineteen-thirties, the papyrus lists the religious rituals to be carried out by the unit throughout the year, many of them focussed on the ruling emperor, Alexander Severus. Major anniversaries in his life were celebrated, usually with a so-called thanksgiving, a religious offering that honored him but stopped short of animal sacrifice and did not treat him explicitly as a god. His deified predecessors, though, all the way back to Julius Caesar, were honored with a full sacrifice to mark their birthdays or accessions. That is to say, almost three hundred years after divus Julius’ assassination, the first god in the imperial family was still regularly receiving an ox on his birthday, from a group of soldiers at the far-eastern edge of the empire.

Some of the very features that make the imperial cult look so unreligious to us were what made it look typically religious to Romans, for whom there was never a division between church and state. Public worship was based not on personal devotion, individual faith, or tenets of “belief” but on the simple axiom that Rome’s military and political success depended on the gods being properly worshipped. If they weren’t, the state would be in danger. Personal piety did not come into it.

Many Imperial Cults in Ancient Rome?

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: The imperial cult was many things to many people. Indeed, it can be said that there was no "imperial cult;" instead, there were many "imperial cults," as appropriate in many different contexts. The emperor never became a complete god, even if he was considered a god, because he was not requested to produce miracles, even for supposed deliverance from peril. Vespasian performed miracles in Alexandria soon after his proclamation as emperor, but these had no precise connection to his potential divine status; he remained an exception in any case. Hadrian never performed miracles, but his young lover Antinous, who was divinized after death, is known to have performed some.[Source: Arnaldo Momigliano (1987), Simon Price (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: Schematically, it can be said that in Rome Augustus favored the association of the cult of his life spirit (genius) with the old cult of the public lares of the crossroads (lares compitales). Such a combined cult was in the hands of humble people (especially ex-slaves). Similar associations developed along various lines in Italy and the West and gave respectability to the ex-slaves who ran them. Augustus's birthday was considered a public holiday. His genius was included in public oaths between Jupiter Optimus Maximus and the penates. In Augustus's last years Tiberius dedicated an altar to the numen Augusti in Rome; the four great priestly colleges had to make yearly sacrifices at it. Numen, in an obscure way, implied divine will. [Source: Arnaldo Momigliano (1987), Simon Price (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

Augustus

In the West, central initiative created the altar of Roma and Augustus outside Lyons, to be administered by the Council of the Three Gauls (12 B.C.). A similar altar was built at Oppidum Ubiorum (Cologne). Later temples to Augustus (by then officially divinized) were erected in Western provinces. The key episode occurred in 15 ce, the year after the official deification of Augustus in Rome, when permission was given to the province of Hispania Tarraconensis for a temple to Divus Augustus in the colonia of Tarraco. Its priests were drawn not just from Tarraco but from the whole province, and Tacitus (Annals 1.78), reporting the decision of 15 ce, notes that the temple set a precedent for other provinces.

In the East, temples to Roma and Divus Julius (for Roman citizens) and to Roma and Augustus (for Greeks) were erected as early as 29 B.C. There, as in the West, provincial assemblies took a leading part in the establishment of the cult. Individual cities were also active: priests of Augustus are found in thirty-four different cities of Asia Minor. The organization of the cult varied locally. There was no collective provincial cult of the emperor in Egypt, though there was a cult in Alexandria. And any poet, indeed any person, could have his or her own idea about the divine nature of the emperor. Horace, for example, suggested that Augustus might be Mercurius (Odes 1.2).

Imperial Cult in Ancient Rome After Augustus

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: Augustus's successors tended to be worshiped either individually, without the addition of Roma, or collectively with past emperors. In Asia Minor the last individual emperor known to have received a personal priesthood or temple is Caracalla. In this province — though not necessarily elsewhere — the imperial cult petered out at the end of the third century. Nevertheless, Constantine, in the fourth century, authorized the building of a temple for the gens Flavia (his own family) in Italy at Hispellum, but he warned that it "should not be polluted by the deceits of any contagious superstitio " — whatever he may have meant by this. [Source: Arnaldo Momigliano (1987), Simon Price (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

It is difficult to say how much the ceremonies of the imperial court reflected divinization of the emperors. Domitian wanted to be called dominus et deus (Suetonius, Domitian 13.2), but this is anomalous and broke the normal convention that the emperor should present himself to the Roman elite as primus inter pares (first among equals). In the third century a specific identification of the living emperor with a known god seems to be more frequent (for instance, Septimius Severus and his wife, Julia Domna, with Jupiter and Juno). When the imperial cult died out, the emperor had to be justified as the choice of god; he became emperor by the grace of god.

Thus Diocletian and Maximian, persecutors of Christianity, present themselves not as Jupiter and Hercules but as Jovius and Herculius, that is, the protégés of Jupiter and Hercules. It must be added that during the first centuries of the Empire the divinization of the emperor was accompanied by a multiplication of divinizations of private individuals, in the West often of humble origin. Such divinization took the form of identifying the dead, and occasionally the living, with a known hero or god. Sometimes the divinization was nothing more than an expression of affection by relatives or friends. But it indicated a tendency to reduce the distance between men and gods, which helped the fortunes of the imperial cult (Wrede, 1981).

In at least the "civilized" parts of both East and West, the principal social change that accompanied these religious changes was the role of local elites in the service of Rome. Holders of the local offices of the imperial cult received prestige in their local communities, as they did for holding other offices or priesthoods, and they might be able to use such offices to further the status of themselves or their families. In the West, ex-slaves with Roman citizenship (who formed a significant upwardly mobile group) could aspire to a public status that articulated their position in the framework of the Roman Empire.

State God Sol Invictus and Monotheism

According to Listverse: For a while there was an official state god was named Sol Invictus (the unconquered sun). Created under emperor Aurelian in 274 AD it continued, overshadowing other cults in importance, until the abolition of paganism under Theodosius I (on February 27, 390). The Romans held a festival on December 25 of Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, “the birthday of the unconquered sun.”

December 25 was the date after the winter solstice, with the first detectable lengthening of daylight hours. There was also a festival on December 19. Though many Oriental cults were practiced informally among the Roman legions from the mid-second century, only that of Sol Invictus was officially accepted and prescribed for the army. Emperors up to Constantine I portrayed Sol Invictus on their official coinage and Constantine decreed (March 7, 321) dies Solis — day of the sun, “Sunday” — as the Roman day of rest. [Source: Listverse, October 16, 2009]

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion, in the Roman Empire: Interest in an abstract deity was encouraged by philosophical reflection, quite apart from suggestions coming from Judaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism. Some have therefore thought it legitimate to consider the cult of Sol Invictus, patronized by the emperor Aurelian, as a monotheistic or henotheistic predecessor of Christianity. But believers would have had to visualize the relation between the one and the many. This relation was complicated by the admission of intermediate demons, either occupying zones between god (or gods) and men or going about the earth and perhaps more capable of evil than of good.[Source: Arnaldo Momigliano (1987), Simon Price (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024