Home | Category: Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

FROM THE SONS OF CONSTANTINE TO THEODOSIUS THE GREAT

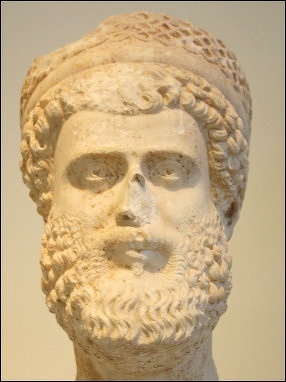

Julian

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: after the massacre of all male family rivals, except for Gallus and Julian, the three sons of Constantine succeeded their father. constantine ii attempted to eliminate his youngest brother, constans i, in 340 and died in battle in Italy. Constans himself was murdered ten years later by his troops in Gaul, who acclaimed a barbarian officer, Magnentius, as his successor. Constantius II eliminated Magnentius in a costly battle at Mursa in modern Croatia and became sole Augustus. But having no children of his own, he turned first to Gallus and them to Julian, the son of Constantine I's half-brother, made him Caesar, and sent him to Gaul, where he fought with success against the Franks. In 360 Constantius II, who was preparing for war against Persia, demanded reinforcements from Julian's army. The result was an insurrection, and Julian's soldiers acclaimed him Augustus. Constantius treated the action as a rebellion and marched westwards to suppress it, but at Tarsus he took ill and died. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Julian the apostate (361–363) was the last pagan emperor, and during his brief reign he attempted to breathe life into paganism. But the interrupted war against Persia called him to the eastern frontier, and Julian's strategic errors led to disaster. As he was retreating with his army, the Persians launched a sudden attack, and Julian was killed. The army chose a relative unknown, Jovian (363–364) to succeed him, and Jovian made a peace treaty with Persia by which he gave up Nisibis and Singara and agreed not to help the king of Armenia against any attack by Persia. In effect he negated the gains won by Galerius I in 297 while he was still Caesar. His victory was commemorated in the Arch of Galerius, a fragment of which still stands in Thessaloniki. Jovian headed back to Constantinople but died before he reached it.

The army chose a soldier from Pannonia, Valentinian (364–375) as next emperor. He in turn chose his brother valens (364–378) as co-emperor to rule the east with his capital in Constantinople, while Valentinian ruled the west with his base in Milan. In 367 Valentinian made his seven-year-old son, gratian, co-emperor, and when he died the army made Gratian's four-year-old half-brother, Valentinian II, co-emperor (375–392) as well. Gratian was 16 at his father's death, and he and his half-brother reigned on in the west until Gratian was overthrown and killed by a usurper, Maximus, Aug. 25,383. In the east, however, Valens' reign ended in disaster. Visigoths, who had been driven out of the Russian steppe by the Huns, arrived at the Danube and sought new homes within the empire. Valens granted them entry, persuaded by the promise that they would supply recruits for the Roman auxiliaries. But local authorities in Thrace maltreated and robbed them, and in the summer of 377 they rose in rebellion. Valens went into battle without waiting for the reinforcements that Gratian was sending him and was crushed at Adrianople in August of 378: two-thirds of his army was destroyed and he himself was killed. It fell to Valens' widow, Domnica Augusta, to organize the defense of Constantinople and provide direction in the emergency.

Gratian turned to theodosius, who was living in retirement in his native Spain. His father, Count Theodosius, had been an able "Master of the Soldiers" in Britain, where he restored order after a concerted attack on the diocese (367) by the Picts, the Scots, and the Saxons, and rebuilt Hadrian's Wall for the third time. But he had fallen from favor for some reason and had been executed at Carthage (376). Theodosius I (379–395), whom Gratian proclaimed co-Augustus (January of 379), made Thessaloniki his headquarters while he restored order in Thrace. It was not until Nov. 24, 380, that he made a formal advent, or ceremonial entry (adventus ) into Constantinople. Theodosius made peace with the visigoths (382), granting them land across the Danube in Moesia in return for service as auxiliaries under the command of their own leaders. They were to be foederati, translated misleadingly as "federate troops." They served under terms of a treaty that exempted them from taxation and gave them a yearly subsidy, but they did not have the right of intermarriage with Roman citizens. They were not to be assimilated. Taking recruits for the Roman armed forces from foreign sources was by no means new, but these "barbarian" soldiers had been integrated into the army, where they would become familiar with Roman culture and loyal to the empire. These new federate troops owed their loyalty first and foremost to their tribal chiefs. But the settlement served as a stop-gap during Theodosius' lifetime. It was after his death in 395 that problems arose with the emergence of an aggressive Visigothic leader, Alaric.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“History of the Later Roman Empire: From the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian” by J. B. Bury (2011) Amazon.com;

Rome, The Late Empire: Roman Art A.D. 200-400" by Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli, translated by Peter Green (1971) Amazon.com;

“Julian: Rome's Last Pagan Emperor” by Philip Freeman (2025) Amazon.com;

“Theodosius: The Empire at Bay” by Stephen Williams and Gerard Friell (1995) Amazon.com;

“Honorius: The Fight for the Roman West AD 395-423" by Chris Doyle Amazon.com;

“The Last Emperor of Rome” by Robert Steven Habermann (2017) Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome” by Chris Scarre (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Emperors: A Biographical Guide to the Rulers of Imperial Rome 31 B.C. - A.D. 476" by Michael Grant (1997) Amazon.com;

“Emperor of Rome” by Mary Beard (2023) Amazon.com

“Emperor in the Roman World” by Fergus Millar (1977) Amazon.com

“How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2009) Amazon.com

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians” by Peter Heather (2005) Amazon.com

“The Fall of Rome” by Bryan Ward-Perkins (2005) Amazon.com

“Empires and Barbarians” by Peter Heather Amazon.com;

“Defending Constantine: The Twilight of an Empire and the Dawn of Christendom” by Peter J. Leithart (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine” by Noel Lenski Amazon.com;

“The New Empire of Diocletian and Constantine” by Timothy D. Barnes (1982) Amazon.com;

“Armies of the Late Roman Empire, AD 284–476: History, Organization & Equipment” by Gabriele Esposito Amazon.com;

“Twilight of Empire: The Roman Army from the Reign of Diocletian Until the Battle of Adrianople” by Martijn Nicasie (2019) Amazon.com;

Roman Emperors After Constantine

Constantine Dynasty (337–63 A.D.)

empire reunited by Constantine's defeat of Licinius

Constantine II (337–40 A.D.)

Constans (337–50 A.D.)

Constantius II (337–61 A.D.)

Magnentius (350–53 A.D.)

Julian (361–63 A.D.)

Jovian (363–64 A.D.)

Western Roman Empire (after death of Jovian))

Valentinian (364–75 A.D.)

Gratian (375–83 A.D.)

Valentinian II (375–92 A.D.)

Eugenius (392–94 A.D.)

Honorius (395–423 A.D.)

Constantinius III (421 A.D.)

John (423–25 A.D.)

Valentinian III (425–55 A.D.)

Petronius Maximus (455 A.D.)

Avitus (455–56 A.D.)

Majorian (457–461 A.D.)

Severus III (461–65 A.D.)

Anthemius (467–72 A.D.)

Olybrius (472 A.D.)

Glycerius (473–74 A.D.)

Julius Nepos (474–75 A.D.)

Romulus Augustulus (475–76 A.D.)

Eastern Roman Empire (after death of Jovian))

Valens (364–78 A.D.)

Theodosius I (379–95 A.D.)

Arcadius (395–408 A.D.)

Theodosius II (408–50 A.D.)

Marcian (450–57 A.D.)

Leo (457–74 A.D.)

Zeno (474–91 A.D.)

Anastasius (491–518 A.D.)

Julian’s Attempt to Bring Back Paganism

The Emperor Julian ("the Apostate") (born A.D. 332, ruled .361-d.363) ruled about three years about 25 years after Constantine’s death. A follower of Mithraism, which he called "the guide of the souls", he tried to undo the work of Constantine and led a concerted effort to re-instate paganism as the dominant religion in the empire. He may not have expected to uproot the new religion entirely; but he hoped to deprive it of the important privileges which it had already acquired. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: In 360 CE, Julian, a successful general and scholar, was proclaimed Augustus by his troops and became emperor of the Roman Empire. The empire had effectively been Christian since the reign of Constantine roughly half a century before, but Julian wanted to return the Roman Empire to the pagan religion and ideals of its founders. Julian was a believer in widespread cultural tolerance and grew up Christian but in 351 he converted to paganism. Christian sources tell us that Julian didn’t persecute Christians but he did prohibit them from teaching the classics. “If they want to learn literature, they have Luke and Mark: let them go back to their churches and expound them.” With a couple of exceptions, Christian teachers now had to focus on teaching the New Testament, a move that effectively ended the careers of many. [Source: Candida Moss, April 16, Daily Beast,, 2017]

Julian’s scheme didn’t outlaw Christianity but it did tightly control who could educate the future leaders of Roman society. By controlling education and expelling those who did not support his reforms, Julian was able to affect the shape of society. As lauded historian Peter Brown has argued, the same thing happened in 13th-century China, when the Confucian mandirinate drove Buddhism out of the ranks of educated elites.

paganism in the provinces

Like all Emperors, Julian was Pontifex Maximus, Chief Priest of the State Religion. In a letter to Arsacius, he wrote: “The religion of the Greeks does not yet prosper as I would wish, on account of those who profess it. But the gifts of the gods are great and splendid, better than any prayer or any hope . . . Indeed, a little while ago no one would have dared even to pray for a such change, and so complete a one in so short a space of time [i.e., the arrival of Julian himself, a reforming traditionalist, on the throne]. Why then do we think that this is sufficient and do not observe how the kindness of Christians to strangers, their care for the burial of their dead, and the sobriety of their lifestyle has done the most to advance their cause? [Source: Based in part on the translation of Edward J. Chinnock, A Few Notes on Julian and a Translation of His Public Letters (London: David Nutt, 1901) pp. 75-78 as quoted in D. Brendan Nagle and Stanley M. Burstein, The Ancient World: Readings in Social and Cultural History (Englewood Cliffs, NJ; Prentice Hall, 1995) pp. 314-315.

“Each of these things, I think, ought really to be practiced by us. It is not sufficient for you alone to practice them, but so must all the priests in Galatia [in modern Turkey] without exception. Either make these men good by shaming them, persuade them to become so or fire them . . . Secondly, exhort the priests neither to approach a theater nor to drink in a tavern, nor to profess any base or infamous trade. Honor those who obey and expel those who disobey.

“Erect many hostels, one in each city, in order that strangers may enjoy my kindness, not only those of our own faith but also of others whosoever is in want of money. I have just been devising a plan by which you will be able to get supplies. For I have ordered that every year throughout all Galatia 30,000 modii of grain and 60,000 pints of wine shall be provided. The fifth part of these I order to be expended on the poor who serve the priests, and the rest must be distributed from me to strangers and beggars. For it is disgraceful when no Jew is a beggar and the impious Galileans [the name given by Julian to Christians] support our poor in addition to their own; everyone is able to see that our coreligionists are in want of aid from us. Teach also those who profess the Greek religion to contribute to such services, and the villages of the Greek religion to offer the first-fruits to the gods. Accustom those of the Greek religion to such benevolence, teaching them that this has been our work from ancient times. Homer, at any rate, made Eumaeus say: "O Stranger, it is not lawful for me, even if one poorer than you should come, to dishonor a stranger. For all strangers and beggars are from Zeus. The gift is small, but it is precious." [Julian is quoting from the Odyssey, 14-531.] Do not therefore let others outdo us in good deeds while we ourselves are disgraced by laziness; rather, let us not quite abandon our piety toward the gods . . .

“While proper behavior in accordance with the laws of the city will obviously be the concern of the governors of the cities, you for your part [as a priest] must take care to encourage people not to violate the laws of the gods since they are holy . . . Above all you must exercise philanthropy. From it result many other goods, and indeed that which is the greatest blessing of all, the goodwill of the gods . . .

“We ought to share our goods with all men, but most of all with the respectable, the helpless, and the poor, so that they have at least the essentials of life. I claim, even though it may seem paradoxical, that it is a holy deed to share our clothes and food with the wicked: we give, not to their moral character but to their human character. Therefore I believe that even prisoners deserve the same kind of care. This type of kindness will not interfere with the process of justice, for among the many imprisoned and awaiting trial some will be found guilty, some innocent. It would be cruel indeed if out of consideration for the innocent we should not allow some pity for the guilty, or on account of the guilty we should behave without mercy and humanity to those who have done no wrong . . . How can the man who, while worshipping Zeus the God of Companions, sees his neighbors in need and does not give them a dime--how can he think he is worshipping Zeus properly? . . .

Theodosius I

“Priests ought to make a point of not doing impure or shameful deeds or saying words or hearing talk of this type. We must therefore get rid of all offensive jokes and licentious associations. What I mean is this: no priest is to read Archilochus or Hipponax or anyone else who writes poetry as they do. They should stay away from the same kind of stuff in Old Comedy. Philosophy alone is appropriate for us priests. Of the philosophers, however, only those who put the gods before them as guides of their intellectual life are acceptable, like Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics . . . only those who make people reverent . . . not the works of Pyrrho and Epicurus . . . We ought to pray often to the gods in private and in public, about three times a day, but if not that often, at least in the morning and at night.

“No priest is anywhere to attend shameful theatrical shows or to have one performed at his own house; it is in no way appropriate. Indeed, if it were possible to get rid of such shows altogether from the theater and restore the theaters, purified, to Dionysus as in the olden days, I would certainly have tried to bring this about. But since I thought that this was out of the question, and even if possible would for other reasons be inexpedient, I did not even try. But I do insist that priests stay away from the licentiousness of the theaters and leave them to the people. No priest is to enter a theater, have an actor or a chariot driver as a friend, or allow a dancer or mime into his house. I allow to attend the sacred games those who want to, that is, they may attend only those games from which women are forbidden to attend not only as participants but even as spectators.”

Theodosius I (379-395)

Emperor Theodosius (379-95) was the last sole Roman emperor. He went on a massive pro-Christianity campaign. He shut down the Oracle of Delphi, terminated the Olympics and destroyed pagan temples. Following the death of Theodosius I, in 395, the Roman Empire was once again divided into different factions ruled by competing soldier-emperors. Some blamed Theodosius for Rome’s fall. The devout Christian outlawed other faiths, supposedly angering pagan gods.

Theodosius I. succeeded Valens as emperor of the East. He was a man of great vigor and military ability, although his reign was stained with acts of violence and injustice. He continued the policy of admitting the barbarians into the empire, but converted them into useful and loyal subjects. From their number he reënforced the ranks of the imperial armies, and jealously guarded them from injustice. When a garrison of Gothic soldiers was once mobbed in Thessalonica, he resorted to a punishment as revengeful as that of Marius and as cruel as that of Sulla. He gathered the people of this city into the circus to the number of seven thousand, and caused them to be massacred by a body of Gothic soldiers (A.D. 390) [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~].

For this inhuman act he was compelled to do penance by St. Ambrose, the bishop of Milan—which fact shows how powerful the Church had become at this time, to compel an emperor to obey its mandates. Theodosius was himself an ardent and orthodox Christian, and went so far as to be intolerant of the pagan religion, and even of the worship of heretics. In spite of his shortcomings he was an able monarch, and has received the name of “Theodosius the Great.” He conquered his rivals and reunited for a brief time the whole Roman world under a single ruler. But at his death (A.D. 395), he divided the empire between his two sons, Arcadius and Honorius, the former receiving the East, and the latter, the West.

Theodosius Makes Christianity the State Religion and Bans Paganism

Constantine I’s actions beginning in A.D. 311 paved the way for the toleration of Christianity but Christianity did not become the legal religion of the Roman Empire until the reign of Theodosius I (A.D. 379-395). He not only made Christianity the official religion of the Empire, he declared other religions illegal.

The Codex Theodosianus reads: “XV.xii.1: Bloody spectacles are not suitable for civil ease and domestic quiet. Wherefore since we have proscribed gladiators, those who have been accustomed to be sentenced to such work as punishment for their crimes, you should cause to serve in the mines, so that they may be punished without shedding their blood. Constantine Augustus. [Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. IV: The Early Medieval World, pp. 69-71.

“XVI.v.1: It is necessary that the privileges which are bestowed for the cultivation of religion should be given only to followers of the Catholic faith. We desire that heretics and schismatics be not only kept from these privileges, but be subjected to various fines. Constantine Augustus.

“XVI.x.4: It is decreed that in all places and all cities the temples should be closed at once, and after a general warning, the opportunity of sinning be taken from the wicked. We decree also that we shall cease from making sacrifices. And if anyone has committed such a crime, let him be stricken with the avenging sword. And we decree that the property of the one executed shall be claimed by the city, and that rulers of the provinces be punished in the same way, if they neglect to punish such crimes. Constantine and Constans Augusti.

“XVI.vii.1: The ability and right of making wills shall be taken from those who turn from Christians to pagans, and the testament of such an one, if he made any, shall be abrogated after his death. Gratian, Valentinian, and Valens Augusti.

“XI.vii.13: Let the course of all law suits and all business cease on Sunday, which our fathers have rightly called the Lord's day, and let no one try to collect either a public or a private debt; and let there be no hearing of disputes by any judges either those required to serve by law or those voluntarily chosen by disputants. And he is to be held not only infamous but sacrilegious who has turned away from the service and observance of holy religion on that day. Gratian, Valentinian and Theodosius Augusti.

“XV.v.1: On the Lord's day, which is the first day of the week, on Christmas, and on the days of Epiphany, Easter, and Pentecost, inasmuch as then the [white] garments [of Christians] symbolizing the light of heavenly cleansing bear witness to the new light of holy baptism, at the time also of the suffering of the apostles, the example for all Christians, the pleasures of the theaters and games are to be kept from the people in all cities, and all the thoughts of Christians and believers are to be occupied with the worship of God. And if any are kept from that worship through the madness of Jewish impiety or the error and insanity of foolish paganism, let them know that there is one time for prayer and another for pleasure. And lest anyone should think he is compelled by the honor due to our person, as if by the greater necessity of his imperial office, or that unless he attempted to hold the games in contempt of the religious prohibition, he might offend our serenity in showing less than the usual devotion toward us; let no one doubt that our clemency is revered in the highest degree by humankind when the worship of the whole world is paid to the might and goodness of God. Theodosius Augustus and Caesar Valentinian.

Stilicho

“XVI.i.2: We desire that all the people under the rule of our clemency should live by that religion which divine Peter the apostle is said to have given to the Romans, and which it is evident that Pope Damasus and Peter, bishop of Alexandria, a man of apostolic sanctity, followed; that is that we should believe in the one deity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit with equal majesty and in the Holy Trinity according to the apostolic teaching and the authority of the gospel. Gratian, Valentinian and Theodosius Augusti.

“XVI.v.iii: Whenever there is found a meeting of a mob of Manichaeans, let the leaders be punished with a heavy fine and let those who attended be known as infamous and dishonored, and be shut out from association with men, and let the house and the dwellings where the profane doctrine was taught be seized by the officers of the city. Valentinian and Valens Augusti.

Another translation of “Theodosian Code XVI.i.2 reads: “It is our desire that all the various nation which are subject to our clemency and moderation, should continue to the profession of that religion which was delivered to the Romans by the divine Apostle Peter, as it has been preserved by faithful tradition and which is now professed by the Pontiff Damasus and by Peter, Bishop of Alexandria, a man of apostolic holiness. According to the apostolic teaching and the doctrine of the Gospel, let us believe in the one diety of the father, Son and Holy Spirit, in equal majesty and in a holy Trinity. We authorize the followers of this law to assume the title Catholic Christians; but as for the others, since in out judgment they are foolish madmen, we decree that the shall be branded with the ignominious name of heretics, and shall not presume to give their conventicles the name of churches. They will suffer in the first place the chastisement of divine condemnation an the second the punishment of out authority, in accordance with the will of heaven shall decide to inflict. [Source: Henry Bettenson, ed., Documents of the Christian Church, (London: Oxford University Press, 1943), p. 31]

General Stilicho

The Vandal general Stilicho effectively ruled the western Roman empire (395 - 408 AD) on behalf of Theodosius's son, Honorius. He fought off the Goth Alaric, but lost influence when other barbarians overran the Rhine and Danube provinces. After Stilicho was executed, Honorius was powerless against Alaric who sacked Rome in 410 AD. [Source: Dr Jon Coulston, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

When the youthful Honorius was made emperor in the West, he was placed under the guardianship of Stilicho, an able general who was a barbarian in the service of Rome. As long as Stilicho lived he was able to resist successfully the attacks upon Italy. The first of these attacks was due to jealousy and hatred on the part of the Eastern emperor. The Goths of Moesia were in a state of discontent, and demanded more extensive lands. Under their great leader, Alaric, they entered Macedonia, invaded Greece, and threatened to devastate the whole peninsula. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The Eastern emperor, Arcadius, in order to relieve his own territory from their ravages, turned their faces toward Italy by giving them settlements in Illyricum, and making their chief, Alaric, master-general of that province. From this region they invaded Italy, and ravaged the plains of the Po. But they were defeated by Stilicho in the battle of Pollentia (A.D. 403), and forced to return again into Illyricum. The generalship of Stilicho was also shown in checking an invasion made by a host of Vandals, Burgundians, Suevi, and Alani under the lead of Radagaisus (A.D. 406). Italy seemed safe as long as Stilicho lived; but he was unfortunately put to death to satisfy the jealousy of his ungrateful master, Honorius (A.D. 408). \~\

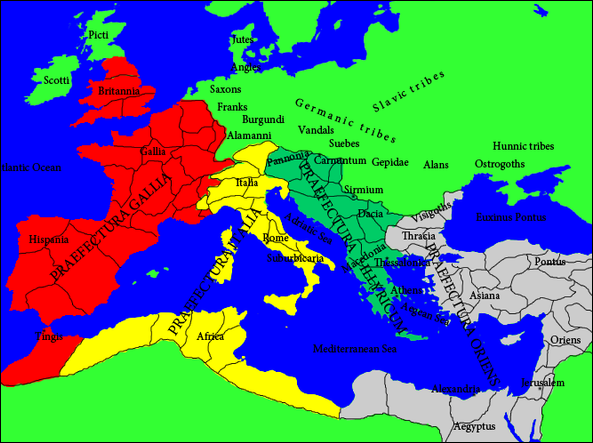

After Theodosius: A Divided Empire Once Again

The death of Theodosius in A.D. 395 marks an important epoch, not only in the history of the later Roman Empire but in the history of European civilization. From this time the two parts of the empire—the East and the West—became more and more separated from each other, until they became at last two distinct worlds, having different destinies. The eastern part, the history of which does not belong to our present study, maintained itself for about a thousand years with its capital at Constantinople, until it was finally conquered by the Turks (A.D. 1453). The western part was soon overrun and conquered by the German invaders, who brought with them new blood and new ideas, and furnished the elements of a new civilization. We have now to see how the Western Empire was obliged finally to succumb to these barbarians, who had been for so many years pressing upon the frontiers, and who had already obtained some foothold in the provinces. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The great invasions which began during the reign of Honorius (A.D. 395-423) continued during the reign of Valentinian III. (A.D. 425-455). As Valentinian was only six years of age when he was proclaimed emperor, the government was carried on by his mother, Placidia, who was the sister of Honorius and daughter of Theodosius the Great. Placidia was in fact for many years during these eventful times the real ruler of Rome. Her armies were commanded by Aëtius and Boniface, who have been called the “last of the Romans.”

Praetorian Prefectures of the Roman Empire 395 AD

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024