Home | Category: Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

FALL OF THE ROME

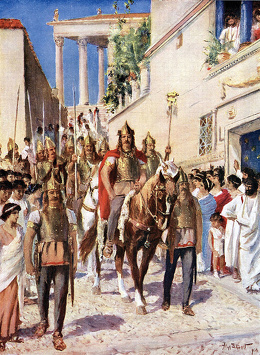

Sacking of Rome by the Visigoths on August 24, 410

Rome was sacked five times: by the Gauls in 387 B.C.; by the Visigoths in A.D 410, the Vandals in 455, and later by the Saracens in 846 and by the Normans in 1084. Rome was invaded for the first time when it was the center of the Roman Empire at midnight August 24, 410 when the Visigoth king Alaric and his hordes poured in through the gates around Rome. Rome was sacked again by the Vandals under the command of their king Genseric in 455. The historian Adrian Goldsworthy wrote that the barbarian invaders “struck at a body made vulnerable by prolonged decay.”

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: By this time, the Roman Empire was centered in Constantinople in the east, and even Western Roman emperors lived in Milan (then called Mediolanum) or Ravenna in northern Italy. But Rome was the "eternal city" and the sacred heart of the empire, and many of the empire’s inhabitants saw this as the end. "The cultural shock was resounding … but the practical impact seems limited," William Bowden, an professor of Roman archaeology at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom, told Live Science.[Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, February 3, 2023]

The final blow for Rome came in 476. The last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustus, was forced to abdicate and the Germanic general Odoacer (c. 433–493), took control of the city. This date marked the end of the Western Roman Empire and its dominance in the Western world. Italy eventually became a Germanic Ostrogoth kingdom. The Ostrogoths (ruled Rome 454-93) and the Lombards (ruled Rome 566-68) invaded from positions in the Balkans and moved in on Rome from what is now northern Italy. As Rome declined, the power of the eastern provinces grow into the strong Byzantine Empire. People in Rome still spoke Ostrogoth as late as 1780.

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“At the Gates of Rome: The Battle for a Dying Empire” by Don Hollway (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Visigoths from the Migration Period to the Seventh Century: An Ethnographic Perspective” by Peter Heather Amazon.com;

“Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric” by Michael Kulikowski Amazon.com;

“Empress Galla Placidia and the Fall of the Roman Empire” by Kenneth Atkinson (2020) Amazon.com;

“How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2009) Amazon.com

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians” by Peter Heather (2005) Amazon.com

“The Fall of Rome” by Bryan Ward-Perkins (2005) Amazon.com

“Empires and Barbarians” by Peter Heather Amazon.com;

“Rebels Against Rome: 400 Years of Rebellions Against the Rule of Rome” by Stephen Dando-Collins ((2023) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Revolution” (The Fall of the Roman Empire Series, Book 1 of 4) by Nick Holmes (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Fall of Rome: End of a Superpower” (The Fall of the Roman Empire Series, Book 2 of 4) by Nick Holmes (2023) Amazon.com;

“Defending Constantine: The Twilight of an Empire and the Dawn of Christendom” by Peter J. Leithart (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine” by Noel Lenski Amazon.com;

“The New Empire of Diocletian and Constantine” by Timothy D. Barnes (1982) Amazon.com;

“Armies of the Late Roman Empire, AD 284–476: History, Organization & Equipment” by Gabriele Esposito Amazon.com;

“Twilight of Empire: The Roman Army from the Reign of Diocletian Until the Battle of Adrianople” by Martijn Nicasie (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire” by Kyle Harper (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Climate of Rome and the Roman Malaria” by Corrado Tommasi-Crudeli and Dick Charles Cramond (Classic Reprint) Amazon.com

“The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World” by Catherine Nixey (2017) Amazon.com

“Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome” by Chris Scarre (2012) Amazon.com;

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

When Did Rome Fall?

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: The "Fall of Rome" usually refers to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century A.D. But historians don't agree about the exact date, nor about its causes. And some historians argue that the Roman Empire lasted until it fell in the East, centuries later. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, February 3, 2023]

At its height around A.D. 100, the Roman Empire stretched from modern Britain, France and much of Germany in the northwest to Egypt, Israel and Jordan in the southeast, and from what are now Morocco and Spain to Romania, Armenia and Iraq. Later emperors divided it into more manageable pieces, resulting in the Western and Eastern Roman Empires. But by the end of the fifth century A.D., the Western Roman Empire, from Britain to Italy, had collapsed and been replaced by a patchwork of "barbarian" kingdoms. "Part fell to invaders, and part disintegrated," Bryan Ward-Perkins, a historian at the University of Oxford and author of "The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization" (Oxford University Press, 2006), told Live Science. "What difference this made to people on the ground is disputed."

Some historians regard Aug. 24, 410, as the decisive date of the fall of Rome. On this date, an army of Visigoths sacked the city of Rome — the first time since it had been overrun by Gauls during the early Roman Republic, almost 800 years earlier. The Visigoths (Western Goths) had fled the Huns' invasions of Eastern Europe in the fourth century. But in 378, after defeating a Roman army at the Battle of Adrianople (now Edirne, Turkey), the Visigoths were given lands on the empire's northern border to control and guard themselves from invaders. However, a few decades later, they again began marauding the empire; in 408, they invaded Italy, and in 410, they besieged and sacked Rome. As city sackings go, it doesn't sound too bad: Many famous monuments and buildings were untouched, and because the Visigoths were Christians, they allowed people to take refuge in churches. The Visigoths withdrew from Italy a few years later.

Some historians regard the formal end of the Western Roman Empire as taking place decades later, on Sept. 4, 476, when Odoacer, the first barbarian king of Italy, forced the young emperor Romulus Augustulus to abdicate. Odoacer had been a Roman general of Germanic descent who professed loyalty to the Eastern Roman emperor, and he took Romulus captive at Ravenna after defeating the 16-year-old's father in battle. Odoacer didn't kill Romulus, however; because of his youth, he was instead given a pension and sent to live with relatives. (Odoacer ruled from Ravenna until 493, when he was killed by an invading Ostrogoth — Eastern Goth — army under their leader, Theodoric the Great, who established a powerful new kingdom in Italy.) "It's kind of an important moment," Peter Heather, a historian at King's College London and author of "The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians" (Oxford University Press, 2007), told Live Science. "Odoacer sent the imperial vestments of the West back to Constantinople, along with delegation from the Senate of Rome, and the delegation says, 'There's no longer any need for an emperor in the West.'" By this time, many regions of the Western empire were already effectively independent kingdoms, but "if you're looking for a symbolic moment, it's a pretty good one," Heather said.

By the fifth century A.D., however, the focus of the empire had shifted east to Constantinople, now Istanbul. Once the Greek city of Byzantium, the city was rebuilt in A.D. 330 by the emperor Constantine the Great, who transferred the imperial capital to his "New Rome." "My own view is that the eastern half of the Roman Empire is still the Roman Empire," Heather said. "It's not unchanging, but there is a sort of continuity of change, not any great rupture."

Although Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453, Heather sees its decline in the Arab invasions from 632 until 661, when they captured Egypt, the Levant, and parts of Anatolia from the Eastern Roman Empire. "The Arabs take about three-quarters of the empire's revenue and about three-quarters of its territory," he said. "It's a totally different kind of entity after the Arab conquest. … it reduces the empire from a global power to a regional power."

Alaric's Sacking of Rome in A.D. 410

Rome was invaded at midnight August 24, 410 when Visigoth King Alaric and his hordes of Germanic and Scythian tribesmen poured in through the gates around Rome. For three days the city was given up to plunder. With Stilicho dead, Italy was practically defenseless. Alaric at the head of the Visigoths (West Goths) immediately invaded the peninsula, and marched to Rome. He was induced to spare the city only by the payment of an enormous ransom. But the barbarian chief was not entirely satisfied with the payment of money. He was in search of lands upon which to settle his people. Honorius refused to grant this demand, and after fruitless negotiations with the emperor, Alaric determined to enforce it by the sword. Alaric then overran southern Italy and made himself master of the peninsula. He soon died, and his successor, Adolphus (Ataulf), was induced to find in Gaul and Spain the lands which Alaric had sought in Italy. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

On Rome in 410, Tony Perrottet wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Rome was a megalopolis where glittering avenues, monuments and arches littered the landscape. A census listed 46,602 multistory tenement buildings, 1,790 palatial villas, 856 bathhouses, 28 libraries and 1,352 fountains, not to mention ten aqueducts and a sewage system. However, the city had fallen on hard times since the golden age of great emperors, like Trajan, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius, more than two centuries earlier. Its cosmopolitan population had shrunk from one million to 600,000, and lawlessness reigned in many streets; the gladiatorial spectacles in the Colosseum were shut down in 404, leaving the chariot races as the main public entertainment. But even in decay there was no rival to Roma Aeterna, the Eternal City, Caput Mundi, the Head of the World, invincible and invulnerable … or so its citizens had believed for some 800 years. [Source: Tony Perrottet, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2023]

The main royal palace exuded all the ancient splendor and confidence of the Roman Empire, the greatest the Western world had ever seen. The floors and walls of the palace were a kaleidoscope of colored marble embedded with gold and precious gems. Silver fountains burbled in the courtyards. Antique statues of military heroes and illustrious Caesars jostled with artwork and trophies brought back by the conquering legions from far-flung corners of the Mediterranean.

But In 410, Rome’s situation was teetering toward the unimaginable. Camped in the countryside around its titanic, marble-sheathed defensive walls was a vast army of some 100,000 warriors led by Alaric, the king of the Visigoths (western Goths), who had marched from the Balkans under the banner of a black crow. The enemy army besieged Rome for three months, blocking its 12 gates and all transport on the Tiber River.

The city was on its knees. The population was starving. Bodies piled up in the streets. Rumors of cannibalism spread. Disease ran rampant. Many pagans blamed the Christians. Theodosius the Great, had ordered dozens of pagan temples in the city closed, snuffed out the sacred flames of the Vestal Virgins and banned the sacrifices to the ancient gods who had protected Rome from enemy incursion for eight centuries.

Honorius, Emperor of Rome When It Was Sacked in 410

Honorius (384– 423) was Roman emperor from 393 to 423. He was the younger son of emperor Theodosius I and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla. After the death of Theodosius in 395, Honorius, under the regency of Stilicho, ruled the western half of the empire while his brother Arcadius ruled the eastern half. His reign over the Western Roman Empire was notably precarious and chaotic. [Source Wikipedia]

Tony Perrottet wrote in Smithsonian magazine:Honorius proved to be an extravagantly incompetent ruler. He was as dimwitted as his older brother Arcadius, who was derided by critics for his “halting speech” and “drooping eyes,” and who allowed his courtiers to lead him “like an ox.” Another scathing description of Arcadius as a spineless sensualist, “living the life of a jellyfish,” could equally have applied to Honorius, whose indifference to matters of state would prove disastrous. The daily business of running the empire often fell to the many capable women in court, such as Placidia’s cousin Serena, who married the general Stilicho and managed affairs from Rome while he went on campaign after the first eruption of Alaric and his Visigoths into Italy in 401. Stilicho’s resounding victories in the next two years restored Romans’ confidence: The barbarian threat had been defused, just as it had been many times over centuries past. [Source: Tony Perrottet, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2023]

The callow Honorius had never set foot on the battlefield, but he claimed the honor of a military triumph in 404 as Stilicho’s superior. The victory parade ended on the Capitoline Hill, the city’s most sacred point, presided over by the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. But in a break with tradition, the Christian Honorius declined to offer sacrifice to the king of the gods.

Although Rome’s sacred sites had been shuttered and their rites banned, many citizens remained staunchly pagan in their hearts, and their city an island of heathenism. Now, some pagans muttered in private that the offended Jupiter would withdraw his protection. Little that happened during the next six years offered proof to dissuade them.

The triumph of 404 proved to be a false dawn. From his refuge in Ravenna, Honorius hopelessly mismanaged the defense of the Western Empire. In 408, he became suspicious of Stilicho and had his most talented general arrested and beheaded. He then bungled relations with the Goths, refusing to negotiate with Alaric over his demand to help his people find food, yet failing to prepare an army to confront him. While Honorius ignored his overtures, Roman troops massacred the families of Gothic soldiers who were serving as mercenaries in the legions.

Alaric’s Advance on Rome

In the Eastern Roman Empire, Arcadius died in May 408 and was replaced by his son Theodosius II; Stilicho, the effective leader of the Western Roman Empire, appears to have planned to march to Constantinople, and to install there a regime loyal to himself. He may also have intended to give Alaric a senior official position and send him against the rebels in Gaul. Before Stilicho could do so a bloody coup against his supporters took place at Honorius's court. Stilicho's small escort of Goths and Huns was commanded by a Goth, Sarus, whose Gothic troops massacred the Hun contingent in their sleep, and then withdrew towards the cities in which their own families were billeted. Stilicho ordered that Sarus's Goths should not be admitted, but, now without an army, he was forced to flee for sanctuary. Agents loyal to Honorius promised Stilicho his life, but instead betrayed and killed him. The conspirators seem to have let their main army disintegrate and had no policy except hunting down supporters of Stilicho. Italy was left without effective indigenous defence forces thereafter. [Source Wikipedia]

Alaric was again declared an enemy of the emperor. Honorius’s men then massacred the families of the federate troops (as presumed supporters of Stilicho, although they had probably rebelled against him), and the troops defected en masse to Alaric. Many thousands of barbarian auxiliaries, along with their wives and children, joined Alaric in Noricum. As a declared 'enemy of the emperor', Alaric was denied the legitimacy that he needed to collect taxes and hold cities without large garrisons, which he could not afford to detach. He again offered to move his men, this time to Pannonia, in exchange for a modest sum of money and the modest title of Comes, but he was refused because Honorius's regime regarded him as a supporter of Stilicho.

In 408, Alaric marched across the Alps with an estimated 30,000 soldiers and 150,000 camp followers. Many of the men were newly enlisted and understandably motivated to avenge their murdered families. In September 408, Alaric blockaded Rome. Tony Perrottet wrote in Smithsonian magazine: As Romans were pushed to near-starvation, the Senate paid Alaric a ransom of 42 wagons full of treasure, although the Visigoths remained in Italy. In the spring of 410, Honorius agreed to meet Alaric, but even though the Visigoth army was constantly being reinforced, soon numbering 100,000 men at arms, the Roman treated the Goth’s demands with disdain, and negotiations came to nothing. Until now, Alaric had hesitated to carry his attack on Rome to its bloody conclusion, hoping to come to a compromise. Though a Christian, he apparently also feared the wrath of Roma, the pagan goddess who personified Rome, if he were to violate her sacred city. Superstitious or not, by the summer of 410, he felt he had no choice but to attack in order to feed his horde of followers.

No blood was shed. When the ambassadors of the Senate, entreating for peace, tried to intimidate him with hints of what the despairing citizens might accomplish, he laughed and gave his celebrated answer: "The thicker the hay, the easier mowed!" The ransom of 5,000 pounds of gold, 30,000 pounds of silver, 4,000 silken tunics, 3,000 hides dyed scarlet, and 3,000 pounds of pepper was arrived at after much bargaining. Alaric also recruited some 40,000 freed Gothic slaves.

Alaric’s Invasion of Rome

Tony Perrottet wrote in Smithsonian magazine: It was around midnight that the cataclysm began. Placidia would have heard distant sounds of Gothic horns and growing pandemonium around the Salarian Gate in the city’s northwest; not long afterward, flames could be seen rising from the nearby Gardens of Sallust. The Goths had breached the walls. The British-born monk Pelagius, who was also trapped in Rome that same night, used language that echoed the biblical vision of Judgment Day to convey the horror of the moment: “Rome, the mistress of the world, shivered, crushed with fear, at the sound of the blaring trumpets and the howling of the Goths.” St. Jerome, when he heard the dreadful news from Roman refugees, captured the sense of shock: “It is the end of the world!” he wrote. “Words fail me; sobs prevent me from speaking. The city that once subjugated the world has been subjugated in its turn!” [Source: Tony Perrottet, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2023]

Nobody knows how the Visigoths managed to enter the Salarian Gate on the night of August 24. Some said it was opened from within by servants of a pious Christian noblewoman, Faltonia Proba, who wanted to end the Romans’ misery. Another possibility suggested by historians is that it was opened by rebellious slaves, who had no love for the old Roman order and preferred to take their chances with the enemy so reviled by their masters.

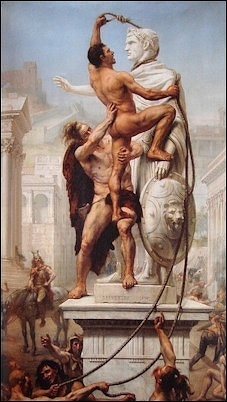

The next three days shook the world. The pillaging began in surprisingly orderly fashion: The Goths were Christians of a sect known as Arianism (versus the “Catholics” of the official church), and Alaric had given strict orders that his men should respect Rome’s holy churches and monasteries, where many terrified citizens found safety. Stories were later told of devout Christian women who were able to carry religious treasures to safety. But other Romans were tortured to reveal their hidden wealth. The Goths stripped statues and palaces of their precious metals and gems, including a four-foot-tall golden menorah once looted from the Temple of Herod in Jerusalem.

Fighting erupted in many parts of the city, and it descended into savagery when Hun mercenaries ran riot. Fires spread; corpses carpeted the splendid avenues. To the horror of Roman aristocrats, all distinctions of birth were forgotten in the chaos; the monk Pelagius wrote: “Everyone was thrown together and shaken with fear; every household had its grief, and an all-pervading terror gripped us. Slave and noble were one. The same specter of death stalked us all.” After three days, the Goths abandoned Rome, where there was no food for the vast army. But refugees from the disaster would spread across the Mediterranean telling tales of horror, traumatizing, for example, the devout bishop St. Augustine in Roman North Africa. Nearly shattered by the news, he began writing his masterwork City of God to explain why such a tragedy could be part of a divine plan.

In Ravenna, meanwhile, the emperor was unfazed. When a courtier rushed in with news that Rome had “perished” (writes ancient chronicler Procopius), Honorius thought that one of his beloved pet roosters named Rome had died, wailing, “And yet it has just eaten from my hands!” The emperor was indifferent to the city’s dire fate. But he was relieved his chicken had survived.

Along a road lined with thousands of pagan graves and the multilayered catacombs of the Christians, the Gothic army traveled after the three-day sack, leading wagons bulging with loot and a contingent of highborn Roman hostages, of whom by far the most valuable was the 20-year-old Placidia.

Procopius's Description of the Sacking of Rome

On Alaric's sacking of Rome in A.D. 410, Procopius of Caesarea (A.D. c.500-after 562 A.D.) wrote in “History of the Wars”: “The Visigoths, separating from the others, removed from there and at first entered into an alliance with the Emperor Arcadius, but at a later time (for faith with the Romans cannot dwell in barbarians), under the leadership of Alaric, they became hostile to both emperors, and, beginning with Thrace, treated all Europe as an enemy's land. Now the emperor Honorius had before this time been sitting in Rome, with never a thought of war in his mind, but glad, I think, if men allowed him to remain quiet in his palace. But when word was brought that the barbarians with a great army were not far off, but somewhere among the Taulantii (in Illyricum), he abandoned the palace and fled in disorderly fashion to Ravenna, a strong city lying just about at the end of the Ionian Gulf, while some say that he brought in the barbarians himself, because an uprising had been started against him among his subjects; but this does not seem to me trustworthy, as far, at least, as one can judge of the character of the man. And the barbarians, finding that they had no hostile force to encounter them, became the most cruel of all men. For they destroyed all the cities which they captured, especially those south of the Ionian Gulf, so completely that nothing has been left to my time to know them by, unless, indeed, it might be one tower or one gate or some such thing which chanced to remain. And they killed all the people, as many as came in their way, both old and young alike, sparing neither women nor children. Wherefore, even up to the present time Italy is sparsely populated. They also gathered as plunder all the money out of all Europe, and, most important of all, they left in Rome nothing whatever of public or private wealth when they moved on to Gaul. But I shall now tell how Alaric captured Rome. [Source: Procopius of Caesarea (c.500-after 562 A.D.): Alaric's Sack of Rome, A.D. 410, “History of the Wars”, III.ii.7-39, written A.D. 550, “Procopius, History of the Wars,” 7 vols., translated by. H. B. Dewing (Cambridge, Mass., and London: Harvard University Press & Wm. Heinemann, 1914; reprint ed., 1953-54), II.11-23]

“After much time had been spent by him in the siege, and he had not been able either by force or by any other device to capture the place, he formed the following plan. Among the youths in the army whose beards had not yet grown, but who had just come of age, he chose out three hundred whom he knew to be of good birth and possessed of valor beyond their years, and told them secretly that he was about to make a present of them to certain of the patricians in Rome, pretending that they were slaves. And he instructed them that, as soon as they got inside the houses of those men, they should display much gentleness and moderation and serve them eagerly in whatever tasks should be laid upon them by their owners; and he further directed them that not long afterwards, on an appointed day at midday, when all those who were to be their masters would most likely be already asleep after their meal, they should all come to the gate called Salarian and with a sudden rush kill the guards, who would have no previous knowledge of the plot, and open the gates as quickly as possible. After giving these orders to the youths, Alaric straightway sent ambassadors to the members of the senate, stating that he admired them for their loyalty toward their emperor, and that he would trouble them no longer, because of their valor and faithfulness, with which it was plain that they were endowed to a remarkable degree, and in order that tokens of himself might be preserved among men both noble and brave, he wished to present each one of them with some domestics.

“After making this declaration and sending the youths no long afterwards, he commanded the barbarians to make preparations for the departure, and he let this be known to the Romans. And they heard his words gladly, and receiving the gifts began to be exceedingly happy, since they were completely ignorant of the plot of the barbarians. For the youths, by being unusually obedient to their owners, averted suspicion, and in the camp some were already seen moving from their positions and raising the siege, while it seemed that the others were just on the point of doing the very same thing. But when the appointed day had come, Alaric armed his whole force for the attack and was holding them in readiness close by the Salarian Gate; for it happened that he had encamped there at the beginning of the siege. And all the youths at the time of the day agreed upon came to this gate, and, assailing the guards suddenly, put them to death; then they opened the gates and received Alaric and the army into the city at their leisure. And they set fire to the houses which were next to the gate, among which was also the house of Sallust, who in ancient times wrote the history of the Romans, and the greater part of this house has stood half-burned up to my time; and after plundering the whole city and destroying the most of the Romans, they moved on.

“At that time they say that the Emperor Honorius in Ravenna received the message from one of the eunuchs, evidently a keeper of the poultry, that Rome had perished. And he cried out and said, "And yet it has just eaten from my hands!" For he had a very large cock, Roma by name; and the eunuch comprehending his words said that it was the city of Rome which had perished at the hands of Alaric, and the emperor with a sigh of relief answered quickly, "But I, my good fellow, thought that my fowl Roma had perished." So great, they say, was the folly with which this emperor was possessed. But some say that Rome was not captured in this way by Alaric, but that Proba, a woman of very unusual eminence in wealth and in fame among the Roman senatorial class, felt pity for the Romans who were being destroyed by hunger and the other suffering they endured; for they were already even tasting each other's flesh; and seeing that every good hope had left them, since both the river and the harbor were held by the enemy, she commanded her domestics, they say, to open the gates by night.

“Now when Alaric was about to depart from Rome, he declared Attalus, one of their nobles, emperor of the Romans, investing him with the diadem and the purple and whatever else pertains to the imperial dignity. And he did this with the intention of removing Honorius from his throne and of giving over the whole power in the West to Attalus. With such a purpose, then, both Attalus and Alaric were going with a great army against Ravenna. But this Attalus was neither able to think wisely by himself, nor to be persuaded by one who had wisdom to offer. So while Alaric did not by any means approve the plan, Attalus sent commanders to Libya without an army. Thus then, were these things going on.

“And the island of Britannia revolted from the Romans, and the soldiers there chose as their emperor Constantinus, a man of no mean station. And he straightway gathered a fleet of ships and a formidable army and invaded both Spain and Gaul with a great force, thinking to enslave these countries. But Honorius was holding ships in readiness and waiting to see what would happen in Libya, in order that, if those sent by Attalus were repulsed, he might himself sail for Libya and keep some portion of his own kingdom, while if matters there should go against him, he might reach Theodosius [Theodosius II, Emperor in the East, 408-450 A.D.] and remain with him. For Arcadius had already died long before, and his son Theodosius, still a very young child, held the power of the East. But while Honorius was thus anxiously awaiting the outcome of these events and tossed amid the billows of uncertain fortune, it so chanced that some wonderful pieces of good fortune befell him. For God is accustomed to succor those who are neither clever nor able to devise anything of themselves, and to lend them assistance, if they be not wicked, when they are in the last extremity of despair; such a thing, indeed, befell this emperor. For it was suddenly reported from Libya that the commanders of Attalus had been destroyed, and that a host of ships was at hand from Byzantium with a very great number of soldiers who had come to assist him, though he had not expected them, and that Alaric, having quarreled with Attalus, had stripped him of the emperor's garb and was now keeping him under guard in the position of a private citizen.

Impact of Alaric's Sacking of Rome

Though Rome no longer had any military significance, its sacking by Alaric in 410 sent shock waves through the Empire. J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: It was in the same year that the western emperor Honorius sent letters to the civitates of Roman Britain urging them to undertake their own defense, which marks the end of a Roman military presence in Britain. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Alaric died of disease soon after the sack of Rome, and his brother Athaulf led the Visigoths into southern Gaul, taking with him Honorius' half-sister, Galla Placidia. A Visigothic kingdom lasted in southern France until it was overthrown by the king of the franks, clovis (486). In 414 the Visigoths invaded Spain and a Visigothic kingdom lasted there until it was overthrown by the Muslim Arabs.

The Vandals were to deal the western empire a mortal blow by capturing Africa. The Asding Vandals were not numerous, but they were led by a leader of genius, Gaiseric, who crossed over from Spain to Africa in 429 and began the conquest. Galla Placidia, who provided what direction there was for the western empire from Ravenna as regent for her young son, Valentinian III, failed to coordinate an adequate defense. Carthage fell in 439. Africa was one part of the western empire that had remained prosperous and its wheat fields fed Rome. Now Vandal conquerors displaced Roman landlords, and since the Vandals adhered to the Arian heresy, Catholics were deprived of their churches after 454 and persecuted. Italy had its own problems. Attila, who made himself leader of the Hunnic horde in 446, ravaged Gaul until the Master of the Soldiers, Aetius, met him in 451 with a combined Roman-barbarian force and worsted him at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields (Châlons). Driven from Gaul, Attila invaded Italy the next year and reached Rome, but he withdrew after a meeting with Pope Leo the Great. He was to die on his wedding night in 453, and after his death his horde disintegrated. Yet Rome was to endure another sack. In 455 Gaiseric and his Vandals took the city, and the looting that followed lasted two weeks, compared to which Alaric's sack had been comparatively mild.

Between 455 and 472 there was a series of short-lived weak emperors who were made and unmade by the "Patrician" Ricimer, who was the power behind the throne until his death in 472. Yet one of Ricimer's choices, Majorian (457–461), was able enough to show that with vigorous leadership something might still have been saved. The last emperor was Romulus Augustulus, the young son of the Master of the Soldiers, Orestes, and he was dethroned by Odoacer, a warlord leading a mixed group of barbarians whom he settled in Italy, seizing one-third of the large estates of the landowners for the purpose. Odoacer sent the imperial insignia to Constantinople with the message that the empire needed only one emperor. But the emperor Zeno regarded Odoacer as an illegitimate ruler and encouraged theodoric the Ostrogoth to invade Italy in 488. After defeating and killing Odoacer, he established an Ostrogothic kingdom.

Galla Placidia, the Roman Princess Captured by the Visigoths

When Alaric and the Visigoths attacked Rome in August 410, the Roman Princess Galla Placidia was in the imperial palace complex on the Palatine Hill in the heart of Rome.Tony Perrottet wrote in Smithsonian magazine:The Emperor Honorius, Placidia’s half-brother, had long since abandoned Rome to its fate. Of the imperial family, only the princess had remained, offering her regal support to the Senate as it worked to stave off disaster.[Source: Tony Perrottet, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2023]

Placidia was taken hostage by the Visigoths. For the next four years, she accompanied the marauding Visigoths around the Mediterranean in what turned into an endless search for grain. As her wagon creaked along the superbly engineered highways, Placidia may at first have tried to maintain her own world of Roman comforts. And yet, historians surmise Placidia would also have been exposed to, and perhaps adapted to, her captors’ way of life. She would have eaten strange Germanic stews around evening fires. To endure the winters outdoors, she probably wore exotic furs and leathers. She may have even tried using soap instead of olive oil while bathing.

Alaric assigned his captive to his brother-in-law, a cavalry leader named Athaulf, who was (the later Roman historian Jordanes writes) “a man of imposing beauty and great spirit.” Athaulf ensured that Placidia “enjoyed all the honor and ceremony due to her imperial rank,” traveling in a padded carriage with at least one slave, and perhaps a small collection of silks and jewels. Placidia would turn the disgrace into an extraordinary advantage.

She evidently discovered that the “barbarians” were far more urbane than the dismissive Romans realized — or the common image passed down to us today. Their warrior-nobles wore trousers rather than togas, but many leaders had been educated in Rome, spoke Latin and Greek fluently, and deeply admired classical art and letters. Alaric himself had trained in Italy to become a mercenary general and had fought alongside Placidia’s father, Theodosius, at the Battle of Frigidus in 394. The xenophobic Romans refused to accept the Goths as equals or deal with them honestly. But during her captivity, Placidia developed a more sympathetic view, and she decided that an alliance between Roman and “barbarian” was the best hope to keep the empire intact.

Galla Placidia Marries Visigoth King

Tony Perrottet wrote in Smithsonian magazine: In January of 414, the captive princess astonished Romans by agreeing to marry this handsome new Visigoth king, apparently quite willingly. “Though not tall of stature,” Jordanes writes, Athaulf “was distinguished for beauty of face and form.” For his part, Athaulf was attracted to Placidia’s “nobility, beauty and chaste purity.” The army was by then crossing southern Gaul, modern France, and a lavish wedding ceremony was held in a villa in Narbonne, a lovely coastal city in today’s south of France. A mixed marriage if ever there was one, the rite was Roman in style but attended by local Roman nobles and Goths alike. Sending a clear message through fashion, Placidia wore imperial silks and Athaulf the armor of a Roman general. Together, the cross-cultural pair advocated a radical dream. As Athaulf explained in his wedding speech, his desire had once been to destroy the empire and turn it into “Gothia” instead of “Romania” with himself as a new Caesar. But now he longed for peace. He and his people were tired of their endless wanderings around southern Europe. Instead of fighting for their own kingdom, the Goths would now become Roman citizens, accept imperial laws, become integrated into Rome’s society and defend its borders. In short, Athaulf and Placidia would renew the ailing empire: The royal house of Theodosius could now be backed by the manpower of the Goths. [Source: Tony Perrottet, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2023]

Athaulf admitted that he had come to this conclusion aided by “the persuasion and advice of his wife, a woman of surpassing intellect and of faith beyond reproach.” It’s very plausible. As the Roman historian Tacitus once noted in surprise, German men, unlike the deeply sexist Romans, valued women’s opinions; they did “not despise [women’s] counsels or make light of their answers.” According to Joyce E. Salisbury, author of the Placidia biography Rome’s Christian Empress, the princess may have privately calculated that this was the only way for her to secure independence: Even if she were ransomed and returned to her doltish brother Honorius, who had no heirs, she would be married off as a pawn in the court’s power game.

As a wedding gift, Athaulf gave his bride 50 young men dressed in silk as her personal guards, each carrying two plates, one piled with gold, the other with precious gems — all plundered from Rome. As marriage hymns were sung, the guests enjoyed a feast featuring Gaulish wines and desserts flavored with rosemary flower honey. It may have been Placidia’s idea that the Visigoths locate their new base in the fertile provinces of Spain, her family’s ancestral homeland. Arriving in Barcino, modern Barcelona, Placidia bore Athaulf a son. Instead of a royal Gothic name, they christened the boy Theodosius after his Roman grandfather, the revered warrior-emperor. The future looked bright.However, after only a few months, the infant Theodosius died. The mourning Placidia and Athaulf wrapped the body in a gold cloth and laid it in a tiny silver coffin, which after a torchlit procession was buried in a chapel.

Worse was to come. In 415, Athaulf was attacked by a resentful servant and stabbed in the groin; the wound soon proved to be lethal. The new Gothic king Sigeric, who seized the throne after Athaulf’s assassination, wanted to remove all threat to his rule and personally butchered Athaulf’s daughters from his first marriage, tearing them from the arms of a bishop who tried to protect them. Placidia was only saved by her royal Roman blood. Instead of being executed, she was forced to walk in front of Sigeric’s horse with other Roman prisoners during Athaulf’s 12-mile funeral procession as an act of humiliation. She was then ransomed for a vast quantity of Roman grain, 600,000 measures, and bundled off to Honorius.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “The Misunderstood Roman Empress Who Willed Her Way to the Top” in Smithsonian magazine smithsonianmag.com

Official Fall of Rome in 476?

The year 476, when Romulus Augustulus was dethroned, is the conventional date for the fall of the Roman Empire. In fact little changed that year. The great landowners were still rich, though they had lost one-third of their estates, and there were still consuls and prefects. But in Constantinople, the last emperor of Theodosius' family, Theodosius II (408–450), though he was anything but vigorous, did provide continuity and stability. The east still had a good recruiting ground for the army in Asia Minor, and Leo I (457–474) rid himself of Aspar, the "First of the Patricians" by counterbalancing his followers with loyal recruits from Isauria. He married his daughter to an Isaurian chief, Tarasis, who became emperor and took the name Zeno (474–491). Thus the eastern empire passed through its time of crisis and survived.

Edward J. Watts wrote in Time: “In September of 476 AD, the barbarian commander Odoacer forced the teenaged Western Roman emperor Romulus Augustus to resign his office. The Constantinopolitan chronicler Marcellinus Comes would write in the 510s that when “Odoacer, king of the Goths, took control of Rome” the “Western Empire of the Roman people … perished.” But no one thought this at the time. The fall of Rome in 476 is a historical turning point that was invented nearly 50 years later as a pretext for a devastating war. The fact that it has since become recognized as the end of an epoch shows how history can be misused to justify otherwise unpalatable actions in the present — and how that misuse can also distort the lessons future generations take from the past. [Source: Edward J. Watts, Time, October 7, 2021]

“Although everyone from schoolchildren to scholars now learn that the Western Roman Empire fell in 476, 5th century Romans did not see anything particularly special about Odoacer’s coup. Nine different Western Roman emperors had risen and fallen since 455 and most of them had been overthrown by barbarian commanders like Odoacer. In four cases, the barbarian generals toppled one emperor and delayed appointing another. One of these imperial vacancies stretched for 20 months, a span longer than the entire reigns of more than 20 previous Roman emperors. Even Romulus Augustus himself was a usurper who assumed the imperial office after an imperfectly executed coup that left Julius Nepos, the legitimate emperor Romulus replaced, still in charge of Western Roman imperial territories in what is now Croatia. In other words, while the West had lost an imperial usurper in 476, it still had a legitimate Roman emperor.

“Odoacer maintained most of the structures of the Roman government during the nearly 17 years he controlled the state. The Senate continued to meet in Rome just as it had for nearly a millennium. Latin remained the language of administration. Roman law governed the land. Roman armies continued to fight and win victories on the frontiers. And Roman emperors appeared on the coins that Odoacer minted. These coins showed Julius Nepos at first and then, after Nepos’s death in 480, they featured the busts of the Eastern Roman emperors who reigned in Constantinople.

“These aspects of Roman life continued after the Gothic ruler Theoderic overthrew Odoacer in 493. Theoderic proved even more successful than Odoacer in reviving Italian fortunes after the political chaos of the mid-5th century. His armies campaigned successfully in modern Croatia, Serbia and France. He made much of Spain into a protectorate for a time. Large scale repairs were made to churches and public buildings throughout Italy. Either Theoderic or Odoacer undertook renovations to the Colosseum following which senators proudly inscribed their names and offices on their seats.

“Rather than imagining that Roman rule had ended in 476, Italians in the late 5th and early 6th centuries spoke about its recovery. Bishop Ennodius of Pavia spoke of the “filth” that Theoderic “washed away from the greater part of Italy,” leaving Rome, as it emerged from “the ashes,” “living again.” Theoderic’s military victories meant that “the Roman empire has returned to its former boundary” and returned “the culture of our ancestors” to Romans who had lived in the regions he reconquered. Ennodius even went so far as to claim that “the revival of Roman renown brought Theoderic forward” as a rival to Alexander the Great because he had sparked a Roman “Golden Age.”

In the Constantinople-based Eastern Roman Empire, the reign of Anastasius (491–518) was a period of growth and recovery. The Danube frontier was reestablished. Anastasius was followed by Justin I (518–527) and then by Justin's nephew, Justinian (527–565) under whom Africa and Italy were recaptured, as well as a foot-hold in Spain. Nonetheless the past could not be restored. Italy was left prostrate by Justinian's war, which destroyed the Ostrogothic kingdom. Moreover, bubonic plague visited Europe in the years following 542, when it first appeared in Constantinople, and it provides as good a date as any for the beginning of the so-called "Dark Ages."

Why Then is 476 Regarded as the Fall of Rome

Edward J. Watts wrote in Time: ““How did it happen that Odoacer’s coup, the beginning of this Roman resurgence, instead came to be seen as the fall of Rome? The answer lies not in Italy but in Constantinople. As Italian power returned under Odoacer and Theoderic, relations with the Eastern Roman Empire in Constantinople deteriorated. By the time of Theoderic’s death in 526, Romans in Constantinople had begun considering the possibility of invading Italy. [Source: Edward J. Watts, Time, October 7, 2021]

“It is at this moment of East-West tension that we can return to Marcellinus Comes. Marcellinus’s Chronicle appeared in the late 510s and represents the first historical work known to claim that Rome fell in 476. Marcellinus’s text also gives away why he said this. Marcellinus describes Odoacer as “the king of the Goths” when he caused the Roman Empire to “perish.” This is a fabrication. Odoacer was not a Goth. Theoderic, however, was a Gothic king and he had taken power from Odoacer. As the Gothic-led Western Roman state found itself in increasing tension with Constantinople, the fall of Rome emerged as a way to justify an Eastern Roman invasion that would restore Italy to Eastern Roman control.

“Marcellinus did not invent this idea in a vacuum. He served in Constantinople as an aide to the future Eastern Roman emperor Justinian, who was at the time the imperial heir apparent. Marcellinus later received several honorific titles from Justinian following the publication of his Chronicle, a work that bluntly hammers home its main theme that the Western Empire had fallen and Justinian’s Eastern Roman Empire should restore it.

Rome Attacked by the Eastern Roman Empire

Edward J. Watts wrote in Time: “This propaganda worked well. In 535, Eastern Roman armies attacked Italy. Justinian explained this aggression by claiming that “the Goths have used force to take Italy, which was ours, and have refused to give it back.” His troops entered the city of Rome in December of 536. On this day, Justinian’s official historian Procopius wrote, “Rome became subject to the Romans again after a time of 60 years.” The number 60 was not arbitrarily chosen. The capture of Rome by the East came 60 years and three months after Odoacer’s coup of 476. [Source: Edward J. Watts, Time, October 7, 2021]

“Despite these initial successes, Justinian’s armies struggled to consolidate control over the peninsula. The Italian war did not conclude until 562 and the fighting devastated both the city of Rome and much of Italy. Goths recaptured Rome in 546, lost it in 547, retook it in 549, and then lost the city for good in 552. Residents of Rome survived by eating weeds, mice and dung during a long Gothic siege in 546. It is estimated that Rome’s population fell from perhaps 500,000 in the mid-5th century to as little as 25,000 in the 560s. Other Italian cities suffered even worse fates. Milan, once Italy’s second largest city, was razed to the ground in 539 with its entire population either killed or enslaved. The Eastern Roman Empire had recovered Italy — and destroyed much of it in the process.

“The Western Roman Empire had clearly fallen by the 560s. Italy was controlled by Justinian, many of its cities were ruined and much of its infrastructure was severely damaged. When later historians looked for the moment when the Western Empire fell, they found Marcellinus and his claim that Rome fell under Odoacer. In the memorable framing by the historian Brian Croke, the fall of Rome in 476 is a manufactured historical turning point that has become an accepted historical fact. But it was Justinian’s invasion, not Odoacer’s coup that decimated Italy and ended the Western Roman state. For 1,500 years, we have picked the wrong time and blamed the wrong person for the fall of Rome.

“This mistake matters for two reasons. First, Marcellinus’s manufactured fall of Rome helped create conditions that permitted Justinian to launch a war that killed hundreds of thousands and destroyed the prosperity that Roman rule had once created in the West. His words had real, deadly and long-lasting consequences.

“Second, the manufactured fall of Rome reveals the unstable boundaries between historical epochs. For 1,500 years, Odoacer’s coup has concluded a cautionary tale about how barbarian commanders in the Roman army ended Rome’s empire. People around the world have scrutinized this story so that their societies may avoid suffering Rome’s fate. But, if we recognize that Rome did not fall in 476, the lessons we take from Roman history become quite different. Rome’s story then does not warn us of the danger of barbarous outsiders toppling a society from within. It instead shows how a false claim that a nation has perished can help cause the very problems its author invented. We ignore this danger at our peril.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Valen's death, Pinterest

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024