Home | Category: Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

ROMAN SOLDIER-EMPERORS

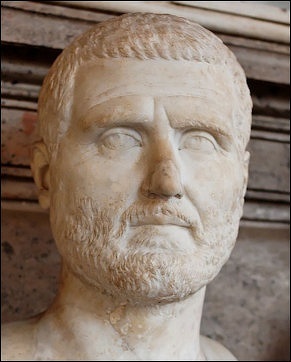

Gordion I, defeated in Africa, committed suicide after the death of his son

Soldier Emperors (235–284 A.D.)

Maximinus I (235–38 A.D.)

Gordian I and II (in Africa) (238 A.D.)

Balbinus and Pupienus (in Italy) (238 A.D.)

Gordian III (238–44 A.D.)

[Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Philip the Arab (244–49 A.D.)

Trajan Decius (249–51 A.D.)

Trebonianus Gallus (with Volusian) (251–53 A.D.)

Aemilianus (253 A.D.)

Gallienus (with Valerian, 253–60 A.D.) (253–68 A.D.)

Gallic Empire (West) Follows the death of Valerian)

Postumus (260–69 A.D.)

Laelian (268 A.D.)

Marius (268 A.D.)

Victorinus (268–70 A.D.)

Domitianus (271 A.D.)

Tetricus I and II (270–74 A.D.)

Palmyrene Empire

Odenathus (c. 250–67 A.D.)

Vaballathus (with Zenobia) (267–72 A.D.)

Claudius II Gothicus (268–70 A.D.)

Quintillus (270 A.D.)

Aurelian (270–75 A.D.)

Tacitus (275–76 A.D.)

Florianus (276 A.D.)

Probus (276–82 A.D.)

Carus (282–83 A.D.)

Carinus (283–84 A.D.)

Numerianus (283–84 A.D.)

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Age of the Soldier Emperors: Imperial Rome, A.D. 244-284" George C. Brauer Jr. (1975) Amazon.com;

“Zenobia: Palmyra’s Warrior Queen (Bat-Zabbai)” by T.S. Dunn (2023) Amazon.com;

“Palmyra and Its Empire: Zenobia's Revolt against Rome” by Richard Stoneman (1995) Amazon.com;

“Aurelian and Probus: The Soldier Emperors Who Saved Rome” by Ilkka Syvänne Amazon.com;

“The Severans: The Changed Roman Empire” by Michael Grant (2011) Amazon.com;

“Septimius Severus” by Anthony R. Birley (1999) Amazon.com;

“Severan Culture” (Reprint) by Simon Swain Amazon.com;

“How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2009) Amazon.com

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians” by Peter Heather (2005) Amazon.com

“The Fall of Rome” by Bryan Ward-Perkins (2005) Amazon.com

“Empires and Barbarians” by Peter Heather Amazon.com;

“Rebels Against Rome: 400 Years of Rebellions Against the Rule of Rome” by Stephen Dando-Collins ((2023) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Revolution” (The Fall of the Roman Empire Series, Book 1 of 4) by Nick Holmes (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Fall of Rome: End of a Superpower” (The Fall of the Roman Empire Series, Book 2 of 4) by Nick Holmes (2023) Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome” by Chris Scarre (2012) Amazon.com;

“Emperor of Rome” by Mary Beard (2023) Amazon.com

“Emperor in the Roman World” by Fergus Millar (1977) Amazon.com

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

Emperors During Period of Military Anarchy (A.D. 235-284)

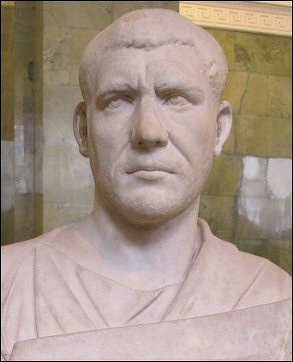

Philip the Arab

Maximus (ruled A.D. 235-238) never set foot in Rome. He was murdered on his way there in 238 while trying to put down a rebellion in northern Italy. He was succeeded by Gordian I and II (ruled A.D. 238); Gordian III (ruled A.D. 238-244); Philip (ruled A.D. 244-249); Decius (ruled A.D. 249-251); Trebonianus Gallus (ruled A.D. 251-253); Valerian, with son Gallienus (ruled A.D. 253-260); Gallienus (ruled A.D. 253-268); Claudius II (ruled A.D. 268-270); Aurelian (ruled A.D. 270-275); Probus (ruled A.D. 276-282); and Carninus and Numerian (ruled A.D. 283-284)

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: There followed a rapid succession of emperors: Gordian I, the elderly governor of Africa and his son Gordian II, who lasted only a little longer than a month, two appointees of the senate, Pupienus Maximus and Balbinus (assassinated July 29, 238), Gordian III (238–244), a boy of thirteen who was the grandson of Gordian I, and Philip the Arab (244–249). Philip and his brother Priscus, who came from a village in Roman Arabia some 55 miles south-southeast of Damascus, were praetorian prefects at Gordian's death, which Philip may have arranged, and he was proclaimed emperor by the army. He faced revolts in the East from Iotapianus, who claimed kinship with Severus Alexander, and on the Danube by Pacatianus. Both were suppressed, but when Philip sent Decius to restore order in the Danubian legions, they proclaimed him emperor. Once Decius defeated Philip, he had to face a massive invasion of the Goths, who crossed the Danube led by their king, Cniva, and lost his life in battle as he campaigned in modern Dobruja. Decius' successor, Trebonianus Gallus (251–253), negotiated the withdrawal of the Goths, who were allowed to take their loot with them. Valerian (253–260), who associated his son Gallienus (253–268) with him as co-emperor, was captured by Shapur I, shahanshah of Persia, outside was walls of Edessa. Valerian was the first emperor to be taken captive. His army decimated by plague, Valerian was trying to negotiate a peace when Shapur seized him and killed him.Gallienus ruled on alone until his murder in 268. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Describing Emperor Gordian (192-238), Gibbons wrote: "Twenty-two concubines, and a library of sixty-two thousand volumes, attested to the variety of his inclinations...By each of his concubines the younger Gordian left three or four children. His literary productions, though less numerous, were by no means contemptible."

One of the few Roman emperors who never had a sculpture of himself commissioned was Plotinis, who abhorred the natural world so much he refused to have a sculpture made in his likeness.

The Petition to the Emperor Philip (Philip the Arab, r. A.D. 243-249):On Official & Military Extortion, A.D. 246 reads: “Most reverend and serene of all emperors, although in your most felicitous times all other persons enjoy an untroubled and calm existence, since all wickedness and oppression have ceased, we, alone experiencing a fortune most alien to these most fortunate times, present this supplication to you. We are unreasonably oppressed and we suffer extortion by those persons whose duty it is to maintain the public welfare. For although we live remotely and are without military protection, we suffer afflictions alien to your most felicitous times. Generals and soldiers and lordlings of prominent offices in the city and your Caesarians, coming to us, traversing the Appian district, leaving the highway, taking us from our tasks, requisitioning our plowing oxen, make exactions that are by no means their due. And it happens thus that we are wronged by extortions. Our possessions are spent on them, and our fields are stripped and laid waste....”

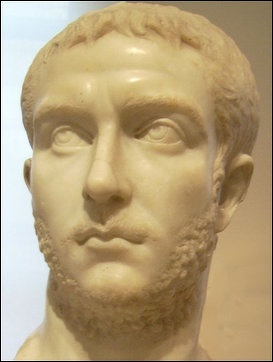

Gallienus

During the reign of the Gallienus (ruled A.D. 253-268), the eastern provinces of present day Spain, France and England broke away under the rival emperor, Postumus (ruled from 260-269) and the eastern provinces of Asia Minor, Syria and Egypt were annexed by the powerful but short-lived city-state of Palmyra. Pat Southern wrote for the BBC: Few recognise the name Gallienus, but without him the Roman empire might have completely disintegrated in the years after 260 AD. This is the extraordinary story of one of Rome's darkest hours....The year 253 A.D. seemed to herald an end to the anarchy. Valerian and his son Gallienus were declared joint emperors, sharing power as some emperors had done in the past. It seemed possible to stem the raids from the north and also deal with the eastern question. Valerian departed for the Persian war, while Gallienus turned to the western provinces. But within seven years of their accession it had all gone wrong. |[Source: Pat Southern, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“In the fateful year 260 AD, Valerian was captured by Shapur, leaving the eastern provinces unprotected. A Palmyrene nobleman called Odenathus gathered an army and fought off the Persians, temporarily stabilising the east. Gallienus acknowledged him because he was in no position to rescue his father or fight the Persians himself. At around the same time, the western provinces of Gaul (modern France) and Germany set up their own Gallic Empire (Imperium Galliarum) under their chosen emperor, Postumus. |::|

“The empire was in danger of splitting up. Gallienus was deprived of control of two large areas and of the bulk of the armies, but he adapted the resources at his disposal, actively fighting off usurpers and tribesmen, dashing back and forth to meet each new threat. He received no thanks for his efforts. Time was the one thing that he needed to reunite the empire, but he didn't get it. In 268 AD, Gallienus was assassinated.

Gallienus and the Third Century Crisis

Gallienus

Dr Jon Coulston of the University of St. Andrews wrote for the BBC: “Gallienus (ruled 253 - 268 AD) held onto the central third of the empire after his father was defeated and captured by the Persians in 260 AD. He had the advantage of controlling the Danubian provinces, which produced the best troops of the empire, and he maximised the impact of his cavalry resources by concentrating them in a single mobile army based in northern Italy, under the command of Aureolus. Institutionally, this cavalry force had been developing since the time of Severus, but Gallienus put a new emphasis on mobility which had implications for later emperors. Gallienus was assassinated after Aureolus rose against him.” [Source: Dr Jon Coulston, BBC, February 17, 2011]

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Gallienus was left in secure control only of Italy, Africa, and Illyricum. The silver denarius was debased until it had only a trace of silver in it, and it appears that much of the economy was carried on by barter. The army had to be paid largely through requisitions in kind. German tribes invaded Gaul, and the Goths raided the Balkans and Asia Minor. In 267 a barbarian tribe known as the Herulians took advantage of a Gothic invasion of the Balkans to sack Athens. There followed a plague epidemic which caused serious loss of life. The nature of the illness is not known, though it was probably not bubonic plague. In the cities of the empire the burden of taxation fell heavily on the curiae. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

The town councils, which were staffed by the well-to-do citizens (curiales ), who were responsible for collecting the taxes and serving on a council, which was once an honor, became something to be avoided by anyone who wanted to preserve his wealth. Pagan cults with expensive festivals could no longer rely on private euergetism. Private donors who had once built public buildings and kept them in repair became scarce. However, it is hard to generalize, since euergetism was largely a thing of the past in Britain, Gaul, and Italy by the end of the third century, though in Africa, which escaped the worst of the turmoil of the third century, it lasted to some degree up to the vandal conquest of the early fifth century.

Gallienus maintained control as best he could in the face of rebellion after rebellion. Senators were excluded from military commands, and an elite cavalry unit was created and based in Milan, under an equestrian commandant. Army generals could now rise from the ranks, and a cadre of new officers recruited in Illyricum emerged. After Gallienus was murdered in 268, they provided a series of able soldier-emperors. It is too easy to dismiss Gallienus as a failure. Without his tenacity in the face of disasters, the empire might have disintegrated.

Devastation by the Goths in the Reign of Gallienus

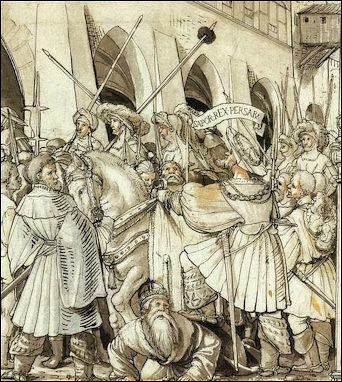

Humiliation of Valerianus

William Stearns Davis wrote: “Under Gallienus, the Empire was in desperate straits and seemed on the eve of dissolution. Since A.D. 250 the Goths had been flinging their hordes over the Danube, and committing devastations which required decades of peace to repair. It is a tribute to the strength of the Empire that it did not perish in the third century. After continuing their havoc for a long time unchecked, they were at last expelled for more than a century, by the arms of Claudius II Gothicus, Aurelian, and Probus. [Source: William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

Jordanes (fl.c.550 A.D.) wrote in “History of the Goths”: “While Gallienus was given over to luxurious living of every sort, Respa, Veduc, and Thuruar, leaders of the Goths, took ship and sailed across the strait of the Hellespont to Asia. There they laid waste many populous cities and set fire to the renowned temple of Diana at Ephesus, which, as we said before, the Amazons built. Being driven from the neighborhood of Bithynia they destroyed Chalcedon, which Cornelius Avitus afterward restored to some extent. [Source: Jordanes: History of the Goths, Chap. 20: The Devastation of the Goths in the Reign of Gallienus, William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West].

“Yet even today, though it is happily situated near the royal city [Constantinople], it still shows some traces of its ruin as a witness to posterity. After their success the Goths recrossed the strait of the Hellespont, laden with booty and spoil, and returned along the same route by which they had entered the lands of Asia, sacking Troy and Ilium on the way. These cities, which had scarce recovered a little from the famous war of Agamemnon, were thus devastated anew by the hostile sword. After the Goths had thus devastated Asia, Thrace next felt their ferocity.”

Claudius II (Claudius Gothicus)

Gallienus was succeeded by Claudius II, called Gothicus after he fought off an invasion of the Goths. Claudius was one of the few who escaped assassination, dying of plague in 270 AD. J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Claudius Gothicus (268–270) was the first of the Illyrian emperors. He first defeated the Alamanni, who had invaded Italy. The Goths were again threatening the Balkans in spite of Gallienus' victories over them in 267, and Claudius moved against them with his general Aurelian and defeated them decisively at Naissus (268), whence his title "Gothicus." He died of plague at Sirmium, the only emperor in this period to die a natural death.[Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

For a period of eighty-eight years—from the death of Marcus Aurelius (A.D. 180) to the death of Gallienus (A.D. 268)—the imperial government had gradually been growing weaker until it now seemed that the empire was going to pieces for the want of a leader. Under the leadership of five able rulers—Claudius II, Aurelian, Tacitus, Probus, and Carus—they again recovered; and they maintained their existence for more than two hundred years in the West and for more than a thousand years in the East. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

One of the reasons of the recent revolts in the provinces had been general distrust of the central authority at Rome. If the Roman emperor could not protect the provinces, the provinces were determined to protect themselves under their own rulers. When a man should appear able to defend the frontiers the cause of these revolts would disappear. Such a man was Claudius II., who came from Illyricum. He aroused the patriotism of his army and restored its discipline. Paying little attention to the independent governors, he pushed his army into Greece to meet the Goths, who had again crossed the Danube and had advanced into Macedonia. By a series of victories he succeeded in delivering the empire from these barbarians, and for this reason he received the name of Claudius Gothicus. The fruits of the victories of Claudius were reaped by his successor Aurelian, who became the real restorer of the empire. \~\

Partial Recovery of the Roman Empire Under Aurelian

Aurelian

Aurelian (ruled A.D. 270-275), a general from the Balkans, rebuilt the empire that had splintered under Gallienus. He retook the eastern province and nearly all of the western provinces only to be murdered by his own guards. He first provided against a sudden descent upon the city by rebuilding the walls of Rome, which remain to this day and are known as the walls of Aurelian. He then followed the prudent policy of Augustus by withdrawing the Roman army from Dacia and making the Danube the frontier of the empire. He then turned his attention to the rebellious provinces; and recovered Gaul, Spain, and Britain from the hand of the usurper Tetricus. He finally restored the Roman authority in the East; and destroyed the city of Palmyra, which had been made the seat of an independent kingdom, where ruled the famous Queen Zenobia. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Pat Southern wrote for the BBC: The next emperor, Aurelian, self-proclaimed 'restorer of the world', brought the divergent parts of the empire back under his control. But the reunification did not halt the constant usurpations and rebellions. With the accession of Diocletian in 284 AD, the empire enjoyed greater stability for the next two decades, and some of the material and financial damage was repaired, although not entirely successfully. [Source: Pat Southern, BBC, February 17, 2011|]

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Aurelian was a tough and able soldier who completed the restoration which Claudius had begun. His first challenge was an invasion of Italy by the Alemanni, who defeated Aurelian near Placentia, but Aurelian recovered to wipe out the Alemanni invaders. He then turned eastward, where Zenobia's empire extended over Syria, Egypt, and most of Asia Minor. He defeated the Palmyrene army in a pitched battle, took the city, and captured the queen, who had attempted flight. But news reached him as he left for Rome that the Palmyrenes had risen in his rear; he returned swiftly, recaptured Palmyra, and laid it waste. Zenobia was exhibited in Aurelian's triumph and ended her life in elegant detention in Rome. In the west, a brief campaign was enough to put an end to the "Gallic empire" under Tetricus and restore imperial rule in Gaul. It was a brilliant achievement. Yet two other actions of his are symptomatic of the times. He gave up the province of Dacia, which Trajan had conquered. Its defense was now too difficult. And he fortified the city of Rome with a circuit wall which still stands and is named after him: the "Aurelian Wall." Rome itself was no longer secure from attack. Aurelian lost his life to a petty military plot. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Conquest of Palmyra and Zenobia

Zenobia

William Stearns Davis wrote: “During the disasters of the middle of the third century A.D. the Asiatic provinces of the Empire were nearly torn away, first by the Persians, then by the rulers of Palmyra. From this dismemberment the Roman world was saved by the Emperor Aurelian, who among his other conquests overcame Zenobia and destroyed Palmyra (273 A.D.), after no puny struggle. [Source: William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

On the conquest of Palmyra by Aurelian (r.270-275 A.D.), Vopiscus wrote: “After taking Tyana and winning a small battle near Daphne, Aurelian took possession of Antioch, having promised to grant pardon to all the inhabitants, and — acting on the counsel of the venerable Apollonius — he showed himself most humane and merciful. Next, close by Emesa [Davis: a very sacred city, and the great seat of the worship of the Syrian sun god Elagabalus], he gave battle to Zenobia and to her ally Zaba — a great battle in which the very fate of the Empire hung in the issue. Already the cavalry of Aurelian were weary, wavering, and about to take flight, when, by divine assistance, a kind of celestial apparition renewed their courage, and the infantry coming to the aid of the cavalry, they rallied stoutly. [Source: Vopiscus, Aurelian's Conquest of Palmyra ( A.D. r.270-275), A.D. 273 William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. ?? [Introduction (adapted from Davis)]

Zenobia and Zaba were defeated, and the victory was complete. Aurelian, thus made master of the East, entered Emesa as conqueror. First of all he presented himself in the temple of Elagabalus, as if to discharge himself of an ordinary vow — but there he beheld the same divine figure which he had seen come to succor him during the battle. Therefore in that same place he consecrated some temples, with splendid presents; he also erected in Rome a temple to the Sun, and consecrated it with great pomp. Afterward he marched on Palmyra, to end his labors by the taking of that city. The robber bands of Syria, however, made constant attacks while his army was on the march; aud during the siege he was in great danger by being wounded by an arrow.

See Separate Article: PALMYRA: HISTORY, ZENOBIA, ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

Anarchy After Aurelian

After Aurelian died anarchy reigned for nine years. However, the successors of Aurelian—Tacitus, Probus, and Carus—preserved what he himself had achieved. The integrity of the empire was in general maintained against the enemies from without and the “tyrants” from within. The successful efforts of the last five rulers showed that the Roman Empire could still be preserved if properly organized and governed. In the hands of weak and vicious men, like Commodus and Elagabalus, the people were practically left without a government, and were exposed to the attacks of foreign enemies and to all the dangers of anarchy. But when ruled by such men as Claudius II. and Aurelian they were still able to resist foreign invasions and to repress internal revolts. The events of the third century made it clear that if the empire was to continue and the provinces were to be held together there must be some change in the imperial government. The decline of the early empire thus paved the way for a new form of imperialism. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Aurelian was followed by the elderly Tacitus (275–276) and then by one of Aurelian's generals, Probus, who continued the work of restoration. His program included the settlement of large numbers of barbarians inside the frontiers and more extensive drafting of barbarian war captives into the Roman military forces. This policy, which later emperors also followed, was once considered a major cause of the Empire's decline, but barbarian recruits who were integrated into the army fought as well as recruits from the provinces, and the settlers were needed to bring land depopulated by pestilence and invasion back into production. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Probus, a strict disciplinarian like Aurelian, was murdered by his troops. His successor, Carus (282–283), captured the Persian capital, Ctesiphon, but was killed ostensibly by a bolt of lightning, though conspiracy is not improbable. Carus' son, Numerian, led the retreat, but he died on the road under suspicious circumstances. In the rivalry for the imperial office that followed, Diocles was proclaimed emperor at Nicomedia by his soldiers (November of 284), and his first act was to slay the praetorian prefect, Aper, accusing him of murdering Numerian. He then took the name diocletian. There followed a struggle with Carus' surviving son, Carinus (283–285), but after his defeat and death, Diocletian became undisputed emperor and undertook a major reorganization of the empire.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024