Home | Category: Age of Caesar

CRASSUS, ROME'S RICHEST MAN

Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus (115-53 B.C.) has often been described as the richest person in Rome. Andrea Frediani wrote in National Geographic History: A military commander who crushed a slave rebellion, Crassus had become a respected orator, patron, and politician, serving as consul twice among other positions. Through a combination of savvy and ruthlessness, he amassed the largest fortune in Rome. With Crassus’ money and connections, many men would have been content, but Crassus was not one of them. [Source Andrea Frediani, National Geographic History, June 12, 2019]

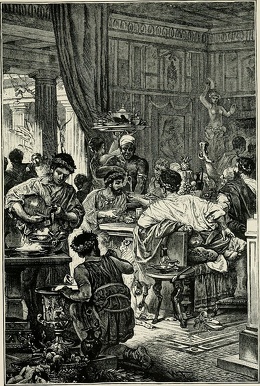

Born into a somewhat wealthy and politically-connected in an era when corruption thrived, Crassus acquired his riches, according to Plutarch, through "fire and rapine." Crassus became so powerful that he financed the army that put down the slave revolt led by Spartacus. To celebrate Spartacus's crucifixion, Crassus hosted a banquet for the entire voting public of Rome (10,000 people) that lasted for several days. Each participant was also given an allowance of three months of grain. His ostentatious displays gave us the word crass. [Source Lionel Casson, Smithsonian magazine]

Crassus made his first fortune redeveloping land taken from the war’s losers, building expensive mansions for the winners. From there he went on to make a massive fortune from mining and banking.After attaining riches and political power the only left for Crassus to do was lead a Roman army in a great military victory. He purchased an army and sent to Syria by Caesar to battle the Parthians. In 53 B.C. Crassus lost the Battle of Carrhae, one of the Roman Empire's worst defeats. He was captured by the Parthians, who according to legend, poured molten gold down his throat when they realized he was the richest man in Rome. The reasoning of the act was that his lifelong thirst for gold should quenched in death.

Peter Stothard wrote in Time magazine: Winning a slave war was little more than a sideshow for Crassus. He had created for himself a new kind of power, the permanent kind, the power to use money behind the scenes, pulling the strings of whichever puppet seemed to be in charge. He was the first tycoon. [Source: Peter Stothard, Time, December 21, 2022]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Crassus: The First Tycoon” by Peter Stothard (2023) Amazon.com;

“Marcus Crassus and the late Roman Republic” by Allen Mason Ward (1977) Amazon.com;

“Fall of the Roman Republic: Six Lives - Marius, Sulla, Crassus, Pompey, Caesar, Cicero” by Plutarch (1988) Amazon.com;

“Defeat of Rome in the East: Crassus, the Parthians, and the Disastrous Battle of Carrhae, 53 BC” (2008) Amazon.com;

“The First Triumvirate: The History of the Men Who Led Rome Near the End of the Republic” by Charles River Editors (2004) Amazon.com;

“Caesar Versus Pompey: Determining Rome’s Greatest General, Statesman & Nation-Builder” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Civil War of Caesar” (Penguin Classics) by Julius Caesar and Jane P. Gardner Amazon.com;

“Mortal Republic: How Rome Fell into Tyranny” by Edward Watts (2020), Illustrated Amazon.com;

“The Last Generation of the Roman Republic” by Erich S. Gruen (1974) Amazon.com

“Caesar, Life of a Colossus” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2006) Amazon.com

“Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar” by Tom Holland (2015) Amazon.com

“Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic” by Tom Holland (2003) Amazon.com

Crassus Early Life

Andrea Frediani wrote in National Geographic History: Born circa 115 B.C., Crassus did not come from an ostentatiously wealthy family. The first-century A.D. historian Plutarch wrote in his work The Parallel Lives that Crassus “lived in a little house,” where “they kept but one table amongst them.” The family might have lived frugally, but they enjoyed an enviable social position. His father, Publius Licinius Crassus, was consul in 97 B.C., a commander in Iberia, (modern Spain) and was honored with a triumph, Rome’s highest military honor, in 93 B.C. [Source Andrea Frediani, National Geographic History, June 12, 2019]

Crassus’ father died in 87 B.C. after becoming embroiled in a political struggle that turned violent. Publius had allied with Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who was vying for power against Gaius Marius. When Marius captured Rome in 87, Publius was either killed or forced to commit suicide. The young Crassus only survived because he was able to escape to Spain.

Crassus found himself having to flee Rome in times of political turmoil. In 87 B.C., when he was only 28, he fled Rome, after Marius had taken control of the city, and Crassus’ father and brother were killed for opposing them. According to the historian Plutarch, Crassus fled to Spain, where his father still had many allies. Even there, people were scared of Marius, so Crassus took refuge in a cave and asked his father's friend, Vibius Paciacus, to send daily provisions to him. It was an ideal hiding spot. Plutarch described it as “not far away from the sea . . . a spring of purest flow issues from the base of the cliff, and natural fissures in the rock . . . admit the light from outside, so that in the day-time the place is bright.” Crassus spent eight months in the cave, only venturing out after learning that his enemies in Rome were no longer a threat.

This conflict brought tragedy to the young Crassus’ life, but it also brought great opportunity. In Spain Crassus started to build his fabulous wealth. He began to recruit men who would eventually join Sulla’s ranks. In the civil war that ensued against Marius, Crassus played a decisive part. His forces fought in the Battle of the Colline Gate in 82 B.C., which would end the civil war between Marius and Sulla. Crassus’ involvement in this war not only brought him glory and money but also forged his reputation for greed: His soldiers complained to Sulla that Crassus would not share the significant spoils he had accrued in the course of the conflict.

The war is also notable for the beginnings of the rivalry between Pompey and Crassus, according to Plutarch. Pompey’s three legions were essential to the efforts to recapture Rome, feats that drew great praise from Sulla, who allowed him to marry his stepdaughter. This acclaim did not escape the notice of Crassus. Plutarch wrote how it “inflamed and goaded him.”

Crassus, the Businessman and Real Estate Tycoon

Crassus was most likely the largest property owner in Rome. He also purchased property with money obtained through underhanded methods. While serving as a lieutenant in the civil war of 88-82 he able to buy land formally held by the enemy at bargain prices, sometimes by murdering its owners. Crassius also opened a profitable training center for slaves. He purchased unskilled bondsmen, trained them and then sold them as slaves for a handsome profit.

Crassus made a fortune in real estate by controlling Rome's only fire department acquiring the land from property owners victimized by fire.. When a fire broke out, a horse drawn water tank was dispatched to the site, but before fire was put out, Crassus or one of his representatives haggled over the price of his services, often while the house was burning down before their eyes. To save the building Crassus often required the owner to fork over title to the property and then pay rent.

Andrea Frediani wrote in National Geographic History: Sulla rewarded Crassus for his service in the war. His gratitude allowed Crassus to be the prime beneficiary of a highly lucrative process of revenge, in which Sulla confiscated the assets of Marius’s followers and then let his allies buy them at bargain prices, sowing the seeds of Crassus’ real estate empire. [Source Andrea Frediani, National Geographic History, June 12, 2019]

Crassus’s keen eye for business, and instinct for any opportunity to increase his wealth, took him into extremely dubious moral territory. He apparently had few qualms when making profit from others’ misfortune. He kept a sharp lookout for fires that would periodically destroy whole sections of the city, particularly in the most popular quarters, where the buildings were stacked together. When a block burned down, owners of adjacent buildings would then sell their own for fear of collapse, and Crassus would swoop on the easy pickings. According to Plutarch, “the greatest part of Rome, at one time or another, came into his hands.”

One of Crassus’ most valuable assets was his enslaved workforce of more than 500 people. Many considered them more valuable than his silver mines or farmland. Crassus educated them to fulfill various roles such as secretaries, goldsmiths, stewards, and servants. Some were trained specialists—architects and masons who could repair and rebuild damaged properties with little expense. After the renovations, Crassus then would sell the buildings at much higher prices.

Crassus and the Spartacus Slave Revolt (73-71 B.C.)

Andrea Frediani wrote in National Geographic History: In the early 70s B.C. Crassus was tapped to put down the slave revolt led by Spartacus in the south of Italy. The revolt had sparked a serious political crisis, and his rebellion defeated even trained Roman legions. Crassus was aware that he had been chosen because Pompey and his forces were unavailable (they were in Hispania), but he was willing to make the most of this opportunity.

Commanding 10 legions, Crassus had more men and resources than the previous commanders sent against Spartacus. Four units were formed by the survivors of previous campaigns against the slaves. In April, 71 B.C., he isolated Spartacus and forced him to fight near the Sele River. He dealt a stunning defeat to the slaves, crucifying 6,000 captives along the Appian Way. But the victory was not complete. At least 5,000 slaves had escaped and were moving toward Gaul. [Source Andrea Frediani, National Geographic History, June 12, 2019]

Before the war with Sertorius was ended, the senate was called upon to meet a far greater danger at home. In order to prepare the gladiators for their bloody contests in the arena, training schools had been established in different parts of Italy. At Capua, in one of these so-called schools (which were rather prisons), was confined a brave Thracian, Spartacus. With no desire to be “butchered to make a Roman holiday,” Spartacus incited his companions to revolt. Seventy of them fled to the crater of Vesuvius and made it a stronghold. Reënforced by other slaves and outlaws of all descriptions, they grew into a motley mass of one hundred thousand desperate men. They ravaged the fields and plundered the cities, until all Italy seemed at their mercy. Four Roman armies were defeated in succession. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The remnant of five thousand men that fled to the north, hoping to escape into Gaul, instead encountered Pompey, who was just returning from Spain, and were destroyed. By this stroke of luck, Pompey had the assurance to claim that in addition to closing the war in Spain, he had also finished the war with the gladiators. While Crassus had crippled the revolt, it was Pompey who ended it. Pompey took credit for the victory and received another triumph, much to the chagrin of Crassus, who was given an ovatio (ovation), a lesser celebration with fewer honors. Recipients were given a myrtle crown instead of the laurel awarded to the superior class of victors.

See Separate Article: SPARTACUS AND THE GREAT ROMAN SLAVE REBELLION europe.factsanddetails.com

Crassus, the Political Benefactor

Crassus was not unlike successful modern businessmen who contribute large sums of money to a political parties in return for favors or high level government positions. He gave loans to nearly every Senator and hosted lavish parties for the influential and powerful. Through shrewd use of his money to gain political influence he reached the position of triumvir, one of the three people responsible for controlling the apparatus of state.

Andrea Frediani wrote in National Geographic History: In an era when rhetoric was essential to further one’s political career, Crassus was considered a highly gifted public speaker. He was also cordial and kind to everyone, even to the humblest people who stopped him on the street. He impressed his fellow Romans by his prodigious memory for names, one of the best assets of his constant and cunning flattery (while also enjoying being flattered). [Source Andrea Frediani, National Geographic History, June 12, 2019]

While known for his greed, Crassus was also capable of being generous. Plutarch described how he opened his house to visitors, donated a tenth of his wealth to the cult of Hercules, and gave enough grain to feed every citizen for three months. He was also generous when it came to lending money to his friends. He would charge them no interest but expected payment in full at the end of the loan. Plutarch wrote: “The Romans, it is true, say that the many virtues of Crassus were obscured by his sole vice of avarice; and it is likely that the one vice which became stronger than all the others in him weakened the rest."

Crassus’ generosity served an important political purpose. The status of a Roman citizen was measured by the number of clients who depended on him. In other words, he was only as important as the men who owed him favors. Lending money to a promising protégé could prove to be a wise investment. If he served the republic with a military command abroad, he could come back with an enhanced reputation, a bulging purse, and a debt to his patron.

The relationship between Crassus and Gaius Julius Caesar grew out of such an arrangement. Crassus correctly saw young Caesar as a man on the make; if he relieved Caesar from debt, that favor would be eventually repaid. Crassus took care of Caesar’s debts before he left on his governorship of Hispania Ulterior (in southern Spain) in 62 B.C., further solidifying the relationship between the two men.

Peter Stothard wrote in Time magazine: Even Caesar himself was Crassus’s puppet at the beginning of his career. Crassus financed Caesar’s election campaigns, making sure at a stupendous cost that Caesar became pontifex maximus, the chief priest, the only man with a house in the Roman Forum. Once Crassus had helped Caesar to his military commands in Gaul, he watched his protégé’s back in Rome, bribing, moneylending, making speeches, and calling in favors in order to ensure, for a while at least, that Caesar became a useful counterweight to Crassus’s lifetime rival, Pompey the Great.

Crassus and Pompey

Andrea Frediani wrote in National Geographic History: Crassus had no problems in dealing with men of different political beliefs, particularly if there was a personal benefit to be made (Julius Caesar had belonged to a different political party). There was, however, one exception to this principle: his rival, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, better known as Pompey or Pompey the Great. [Source Andrea Frediani, National Geographic History, June 12, 2019]

When a Roman general achieved a significant military victory, the city would organize a ceremony, known as a triumphus (triumph) in his honor. Sulla had begrudgingly granted one to Pompey for a victory in the war against Marius despite the fact that Pompey was too young even to be a senator. Eaten up by envy, Crassus became more and more frustrated as Pompey chalked up yet more victories. His jealousy increased as his protégé Caesar claimed even more glory.

Zoelas Bronce of Crassus

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: After Sulla's death populist agitation had begun again. L. Licinius Lucullus (of the Lucullan feasts) went to Bithynia/Pontus to deal with Mithradates, M. Antonius (the father of Mark Antony) Creticus (as he was later called) got a special "imperium infinitum" (power across the borders of different provinces) to deal with the pirates; and Crassus got a special proconsular imperium to deal with the slave revolt of Spartacus. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“There was also pressure on the senators with regard to the courts. Several notorious trials took place at which men of the senatorial class, who had been provincial governors, were acquitted of rapacity in the face of a preponderance of the evidence, and these led to hostility especially on the parts of the equites and to further attempts to restructure the courts. This finally happened in 70. Crassus, fresh from his victory over the rebellious slaves, was a natural for the consulship of 70; his colleague in that office was a surprise. Pompey had returned victorious from Spain, and refused to disband his legions until the Senate agreed to allow him (although he was not qualified according to the electoral laws) to stand for the consulship. The Senate had to agree and Pompey was duly elected. Not a natural ally of Crassus, although both men had been partisans of Sulla, he nonetheless managed to cooperate with him at first. Together they restored the tribunician power; but this would never be the same again after Sulla's attack on it, and for the rest of the Republic's life, with one significant exception, the tribunes figure as the tools of one or another of the senatorial factions. Crassus and Pompey also were behind the Lex Aurelia (sponsored by Cotta) which wrested control of the law courts away from the senate. The new formula for composition of the jurors was one-third senatorial, one-third equites, and one-third tribunes of the treasury (tribunes aerarii); the precise identity of this latter group is disputed, but Brunt has argued plausibly that they were a subset of the equites, such that the reform of the courts was very clearly in favor of that group. But this was the last joint accomplishment of Pompey and Crassus, whose cooperation did not last through the entire term of their office. ^*^

“The trickiness of pinning Pompey to an ideological agenda comes out with the events of 67 and 66. Creticus having failed to suppress the pirates, Pompey allowed himself to be elevated to the command by a Lex Gabinia, passed in the popular assembly but backed by Caesar and of course by Pompey himself. The measure was opposed by the optimates because it gave Pompey a huge force (500 ships, 124,000 men) and unlimited imperium to use them. He would be away from Rome for the rest of the decade. ^*^

First Consulship of Pompey and Crassus (70 B.C.)

Despite tensions between the two, Pompey and Crassus were elected to a joint consulship in 70 B.C., but their rivalry and dislike of each other made it an uneasy partnership. Neither of these men had any great ability as a politician. But Crassus, on account of his wealth, had influence with the capitalists; and Pompey, on account of his military successes, was becoming a sort of popular hero, as Marius had been before him. At this juncture the popular party was now beginning to gather up its scattered forces, and to make its influence felt. With this party, therefore, as offering the greater prospect of success, the two soldiers formed a coalition, and were elected consuls. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Andrea Frediani wrote in National Geographic History: In the following years Pompey continued to accumulate military victories: He rid the Mediterranean Sea of pirates, a constant nuisance for Roman trade. He defeated Mithradates of Pontus (an empire mostly in modern-day Turkey). He also campaigned against other eastern people, from Armenia to Judaea. [Source Andrea Frediani, National Geographic History, June 12, 2019]

The chief event of the consulship of Pompey and Crassus was the complete overthrow of the Sullan constitution. The old power was given back to the tribunes. The legislative power was restored to the assembly, which now could pass laws without the approval of the senate. The exclusive right to furnish jurors in criminal cases was taken away from the senate; and henceforth the jurors (iudices) were to be chosen, one third from the senate, one third from the equites, and one third from the wealthy men below the rank of the equites (the so-called tribuni aerarii). Also, the power of the censors to revise the list of the senators, which Sulla had abolished, was restored; and as a result of this, sixty-four senators were expelled from the senate. By these measures the Sullan regime was practically destroyed, and the supremacy of the senate taken away. This was a great triumph for the popular party. After the close of his consulship, Pompey, with affected modesty, retired to private life. \~\

Caesar Allies Himself with Crassus

Julius Caesar

Caesar furthered his career by allying himself with Crassus, the richest man in Rome. Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “Caesar, in the meantime, being out of his praetorship, had got the province of Spain, but was in great embarrassment with his creditors, who, as he was going off, came upon him, and were very pressing and importunate. This led him to apply himself to Crassus, who was the richest man in Rome, but wanted Caesar's youthful vigour and heat to sustain the opposition against Pompey. Crassus took upon him to satisfy those creditors who were most uneasy to him, and would not be put off any longer, and engaged himself to the amount of eight hundred and thirty talents, upon which Caesar was now at liberty to go to his province. In his journey, as he was crossing the Alps, and passing by a small village of the barbarians with but few inhabitants, and those wretchedly poor, his companions asked the question among themselves by way of mockery, if there were any canvassing for offices there; any contention which should be uppermost, or feuds of great men one against another. To which Caesar made answer seriously, "For my part, I had rather be the first man among these fellows than the second man in Rome."[Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“It is said that another time, when free from business in Spain, after reading some part of the history of Alexander, he sat a great while very thoughtful, and at last burst out into tears. His friends were surprised, and asked him the reason of it. "Do you think," said he, "I have not just cause to weep, when I consider that Alexander at my age had conquered so many nations, and I have all this time done nothing that is memorable." As soon as he came into Spain he was very active, and in a few days had got together ten new cohorts of foot in addition to the twenty which were there before. With these he marched against the Calaici and Lusitani and conquered them, and advancing as far as the ocean, subdued the tribes which never before had been subject to the Romans. Having managed his military affairs with good success, he was equally happy, in the course of his civil government. He took pains to establish a good understanding amongst the several states, and no less care to heal the differences between debtors and creditors. He ordered that the creditor should receive two parts of the debtor's yearly income, and that the other part should be managed by the debtor himself, till by this method the whole debt was at last discharged. This conduct made him leave his province with a fair reputation; being rich himself, and having enriched his soldiers, and having received from them the honourable name of Imperator.

Andrea Frediani wrote in National Geographic History: As Pompey was gathering accolades in the east, the bond that Crassus had established with Julius Caesar bore fruit. After he returned to Rome from his governorship in Spain, Caesar acted as an architect of an alliance (known as the First Triumvirate) among the three great men. Caesar was able to convince both Pompey and Crassus that if they supported his candidacy to the consulship in 59 B.C., he would favor their interests. The three could work together to subvert any opposition in the Roman Senate. This agreement was not strictly illegal, but it did imply a certain disdain for republican institutions, and was eagerly denounced by their enemies, such as Cato and Cicero, when the agreement became public. [Source Andrea Frediani, National Geographic History, June 12, 2019]

Triumvirate of Pompey, Caesar and Crassus (60 B.C.)

In 60 B.C. Crassus joined forces with Caesar and Pompey to form a political alliance that would come to dominate Rome: the so-called First Triumvirate. At the time Caesar was an ambitious military commander beginning a life in politics and Pompey was proud and powerful general. Crassus had once been Caesar’s patron, and the two remained allies. Pompey the Great was a former rival now an uneasy ally. [Source Andrea Frediani, National Geographic History, June 12, 2019]

Andrea Frediani wrote in National Geographic History:Crassus’ decision to unite with these two men could seem baffling. Rich and influential, he joined the triumvirate for both practical and emotional reasons. This alliance with Caesar and Pompey not only helped pass laws favorable to his economic interests, but also gave Crassus the chance to prove his mettle as a soldier and earn the love reserved for Rome’s great commanders. It was a desire that would cost him his life and thrust Rome into civil war.

The Triumvirate (“Group of Three”) was a power-sharing arrangement with Crassus serving as the money man. When Pompey returned to Rome in 61 B.C. the tensions between Crassus and himself had grown. To advert a war between the two, Julius Caesar negotiated an alliance making Pompey, Crassus and Caesar the three leaders of Rome. Once the agreement was signed, the senate was forced to obey. After the Triumvirate was formed, Pompey married Caesar's daughter, Julia, in 59 B.C.. This marriage managed to keep an uneasy peace between Pompey and Caesar.

With the support of Pompey and Crassus, Caesar was elected senior Roman consul in 59 B.C. Together, the trio ensured no step would be taken by the government that did not suit their needs. Caesar enacted land reforms that allotted land to Pompey’s veterans, and altered the tax code, which mollified Crassus’ supporters.

After his consulship ended, Caesar secured the command of the armies and united all of Gaul and invaded Britain, proving himself a ruthless general, while amassing incredible wealth for himself and the Roman treasury. But then catastrophe; his daughter Julia died in 54 B.C. and the following year his ally Crassus was killed in battle, breaking up the powerful triumvirate. Pompey and Caesar, who never really liked each other, clashed.

See Separate Article: CAESAR, POMPEY AND CRASSUS — THE FIRST TRIUMVIRATE europe.factsanddetails.com

Crassus’s Demise — Unraveling Due to Being a Poor Politician and Military Leader

Peter Stothard wrote in Time magazine: Caesar and Pompey both distorted the balance of Roman politics with vast wealth won, stolen if critics were frank, from conquered kings in Rome’s expanding empire. Crassus kept his place in this three-man oligarchy called the ‘Three Headed Monster’ by continuing to use his financial power to balance the influence of his more acclaimed military partners. Senators wore black to show their objection to this change to the traditional system of checks and balances but were powerless against the onslaught of against the dominance of the super-rich.

Gradually Crassus came to see that wealth alone would not be enough to maintain his place at the three-legged top table of Rome. Caesar, rich from Gaul and protected by loyal legions, did not need Crassus’s money anymore. Pompey, after a triumph through the streets of Rome parading giant golden statues and his own head in pearls, was probably for a time even richer than Crassus. [Source: Peter Stothard, Time, December 21, 2022]

So, the man whose power rested on his reputation for wealth decided on a last campaign to keep himself up with Caesar and Pompey. He moved onto his rivals’ turf, trained personal legions as he had trained slaves for his building sites, and prepared to take on a neighbour in war. In 53 B.C., twenty years after the Spartacus rebellion, his fellow oligarchs allowed their colleague to plan an invasion of Parthia, a sprawling empire east of the Euphrates.

But Crassus, for all his commercial and organisational skill, was ill prepared. He was accountable only to Caesar and Pompey. The traditional senatorial systems of diplomacy and intelligence had broken down before the power of money. Crassus knew very little about his Parthian adversaries and, like Trump’s friend, Vladimir Putin, in the Ukraine today, he thought he knew much more than he did.

Crassus expected to face legionaries like his own led by a deal-making pragmatist like himself. Instead, his army faced a swirling mass of archers on ponies, their quivers perpetually replenished from a camel train, a whole new weapon system. Trying to negotiate a retreat, he squabbled over a horse. His head was cut down on to the sand, his mouth filled with molten gold to mark the greed that all the Parthians knew him for.

Death of Grassus

Crassus’s Capture in Syria and Unpleasant Death at the Hands of Parthians

Andrea Frediani wrote in National Geographic History: The consulate in Rome was usually followed by a governorship in foreign provinces. As a part of his agreement with Crassus and Pompey, Caesar took command of Roman forces in Gaul when his consulship was up. In the same way, after Pompey and Crassus were co-consuls in 55 B.C., Pompey took command of territory in Hispania and Africa while Crassus became governor of the Syrian provinces. Crassus, who was about 60, still craved military glory and set his sights on Parthia, an eastern empire in Mesopotamia, and its king, Orodes II. [Source Andrea Frediani, National Geographic History, June 12, 2019]

Crassus began his invasion in 53 B.C., but the Parthians were not easily subdued. Writing more than 200 years after Crassus’ death, Roman historian Cassius Dio related an episode where Crassus boasted to a Parthian ambassador that he would take the western Parthian capital Seleucia; the ambassador laughed, pointed at his palm, and said: “Sooner will hair grow here than you shall reach Seleucia.”

Crassus made a series of blunders, including refusing an offer from the king of Armenia for more soldiers if he would invade Parthia from his country. Instead, Crassus chose to advance through the desert, a decision that left his 43,000 men tired and undernourished. Near Carrhae, a town in what is now Turkey, Crassus engaged the Parthian forces, led by General Surenas who fought with cunning and patience. Surenas dealt a stunning defeat, in which, according to Plutarch: “In the whole campaign, twenty thousand are said to have been killed, and ten thousand to have been taken alive.” Among the dead was Crassus’ own son.

Taken alive, Crassus met his own end at Surenas’s hands. Historians agree Crassus was slain at a meeting to discuss a truce, but sources present different versions of what happened to Crassus post-death. According to Plutarch, his head and one hand are sent to King Orodes II. Cassius Dio relates a more elaborate way of dishonoring Crassus’s remains: “And the Parthians, as some say, poured molten gold into his mouth in mockery.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024