Home | Category: Roman Republic (509 B.C. to 27 B.C.)

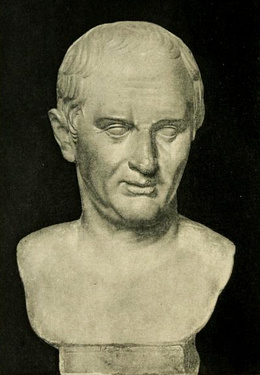

CICERO (105-43 B.C.)

Cicero (106-43 B.C.) was a famous Roman statesman, orator and writer known for his rhetorical style and eloquence. He established himself in the Roman Senate as its master orator and quickly rose through the ranks. In 63 B.C. he took the position of the consulship, the highest Roman office. The day before he had escaped an assassination attempt at the hands of conspirators plotting to overthrow the government.

Cicero did little of consequence during Caesar's rise to power and was unable to do much to halt the demise of the republic. He had a bit of a swan song after Caesar assassination when he placed himself at the head of the Republican party and denounced Marc Antony in a series of famous speech called the “Philippics." When Antony became leader he had Cicero executed for these speeches. According to Plutarch Cicero was taken by a death squad as he attempted to flee to Macedonia. His head and hands were cut off displayed in the Forum, where Antony's wife Fulvia — who Cicero said Antony married for her money — used her hairpins to pierce the tongue of the man who so caustically denounced her husband.

In addition to being an influential politician, Cicero was also the most celebrated defense lawyer of his time — a Roman Johnny Cochran or F. Lee Bailey if you will. He was famous for winning shaky cases with his extraordinary persuasive skills. He once won a Greek poet Roman citizenship, even though he had documents to prove it, by waxing eloquently about contributions poets make to society. Cicero once said, "We are brought in not to say what we stand by in our own opinions, but what is called for by circumstances and the case itself" and if necessary "to pour darkness over the judges."

See Separate Articles: CICERO (105-43 B.C.): LIFE, CAREER, WRITINGS, LEGACY europe.factsanddetails.com ; CICERO'S MURDER, EVENTS AFTER CAESARS'S DEATH AND THE END OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

"Catiline's Conspiracy, The Jugurthine War, Histories " (Oxford World's Classics) 1st Edition

by Sallust Amazon.com;

“Catilinarian Orations” by Cicero Amazon.com

“Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome's Greatest Politician” by Anthony Everitt Amazon.com

“The Storm Before the Storm: The Beginning of the End of the Roman Republic” by Mike Duncan (2017) Amazon.com

“Rome's Last Citizen: The Life and Legacy of Cato, Mortal Enemy of Caesar”

by Rob Goodman, Jimmy Soni, (2014) Amazon.com;

“Uncommon Wrath: How Caesar and Cato’s Deadly Rivalry Destroyed the Roman Republic” by Josiah Osgood (2022) Amazon.com;

“Caesar: Politician and Statesman” by Mattias Gelzer, Peter Needham (1968) Amazon.com;

“Caesar, Life of a Colossus” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2006) Amazon.com

“Cicero: Selected Works” by Marcus Tullius Cicero and Michael Grant Amazon.com;

“Selected Political Speeches (Penguin Classics) by Marcus Tullius Cicero Amazon.com;

“The Republic and The Laws” (Oxford World's Classics) by Cicero Amazon.com;

“On Obligations: De Officiis” (Oxford World's Classics) by Cicero Amazon.com

“Fall of the Roman Republic (Penguin Classics) by Plutarch Amazon.com;

“Fall of the Roman Republic: Six Lives - Marius, Sulla, Crassus, Pompey, Caesar, Cicero” by Plutarch (1988) Amazon.com;

“Mortal Republic: How Rome Fell into Tyranny” by Edward Watts (2020), Illustrated Amazon.com;

“The Fall of the Roman Republic: Roman History, Books 36-40 (Oxford World's Classics)

by Cassius Dio Amazon.com;

“The Roman Republic of Letters: Scholarship, Philosophy, and Politics in the Age of Cicero and Caesar” by Katharina Volk (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Last Generation of the Roman Republic” by Erich S. Gruen (1974) Amazon.com

“The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic” by Fergus Millar Amazon.com

“Imperium: (Cicero Trilogy 1)” by Robert Harris (2006), Novel Amazon.com

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“A Companion to the Roman Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Editor) Amazon.com;

Cicero as Consul

José Miguel Baños wrote in National Geographic History: Wielders of imperium, Roman authority, consuls held executive power in the republic. There were two consuls who each served a one-year term. They held equal power as political and military heads of state. Consuls controlled the army, presided over the Senate, and proposed legislation. On paper, the Senate’s job was to advise and consent, but because the body was made of roughly 600 elite and powerful patrician men, it gained much power and influence. Legislative authority rested with assemblies, most notably the Comitia Centuriata. Plebeians could belong to this body, whose powers included electing officials, enacting laws, and declarations of war and peace.[Source José Miguel Baños, National Geographic History, February 26, 2019]

After taking his seat Cicero as consul, he rose up and addressed his main political rival, Catiline, whom Cicero had just defeated in an election for the consultship: “How long, O Catiline will you abuse your patience? To what lengths will your unbridled audacity carry you? Do you not see that your conspiracy is known to all here? Long ago, Catiline, you ought to have been led forth to execution." Catiline tried to reply. But he was drowned out with cries of “traitor." As he and his followers fled. Some of the followers were grabbed by a mob and killed. Catiline died not long after in a battle.

Cicero was at the height of his power at this time but his reign was brief. He overextended himself by using his power in the Senate to issue death threats that were carried out. He was charged with misuse of power and was banished in 58 B.C. He was allowed to return the next year but never again had the same power or influence.

Cato, Cicero, and the Growing Influence of Caesar

Cato

During the absence of Pompey in the East (67-61 B.C.) the politics of the capital were mainly in the hands of three men—Marcus Porcius Cato, Cicero and Julius Caesar. Cato was the grandson of Cato the Censor; and like his great ancestor he was a man of firmness and of the strictest integrity. He was by nature a conservative, and came to be regarded as the leader of the aristocratic party. He contended for the power of the senate as it existed in the days of old. But lacking the highest qualities of a statesman, he could not prevent the inroads which were being made upon the constitution. On the other hand, Julius Caesar was coming to the front as the leader of the popular party. Though born of patrician stock, he was related by family ties to Marius and Cinna, the old leaders of the people. He was wise enough to see that the cause of the people was in the ascendancy. He aroused the sympathies of the Italians by favoring the extension of the Roman franchise to cities beyond the Po. He appealed to the populace by the splendor of the games which he gave as curule aedile. He allied himself to Crassus, whose great wealth and average ability he could use to good advantage. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”:“At this time, Metellus, the high priest, died, and Catulus and Isauricus, persons of the highest reputation, and who had great influence in the senate, were competitors for the office, yet Caesar would not give way to them, but presented himself to the people as a candidate against them. The several parties seeming very equal, Catulus, who, because he had the most honour to lose, was the most apprehensive of the event, sent to Caesar to buy him off, with offers of a great sum of money. But his answer was, that he was ready to borrow a larger sum than that to carry on the contest. Upon the day of election, as his mother conducted him out of doors with tears after embracing her, "My mother," he said, "to-day you will see me either high priest or an exile." When the votes were taken, after a great struggle, he carried it, and excited among the senate and nobility great alarm lest he might now urge on the people to every kind of insolence. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

Cicero, who, in spite of his vanity, was a man of great intellect and of excellent administrative ability; but being a moderate man, he was liable to be misjudged by both parties. He was also what was called a “new man” (novus homo), that is, the first of his family to obtain the senatorial rank. Cicero was made consul, and rose to the highest distinction during the absence of Pompey. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

If Cicero had done nothing else, he would have been entitled to the gratitude of his country for two acts—the impeachment of Verres and the defeat of Catiline. Cicero stood for law and order, and generally for constitutional government. By his impeachment of Verres, the corrupt governor of Sicily, he brought to light, as had never been done before, the infamous methods employed in the administration of the provinces. He not only brought to light this corruption; he also brought to justice one of the greatest offenders. Then by the defeat of Catiline during his consulship Cicero saved Rome from the execution of a most infamous plot. \~\

Catiline Conspiracy

The Catiline conspiracy was a plot devised by Catiline, with the help of a group of fellow aristocrats and disaffected veterans of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, to overthrow the consulship of Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida. In 63 B.C., Cicero exposed the plot, forcing Catiline to flee from Rome. The conspiracy was chronicled by Sallust in his work “The Conspiracy of Catiline,” and this work remains an authority on the matter. [Source: Wikipedia]

Cicero denouncing Catiline

When Cato threatened to prosecute Catiline, Catiline said that if a fire were kindled against him he would put it out, not with water, but by a general ruin. Ruined himself in fortune, he gathered about him the ruined classes—insolvent debtors, desperate adventurers, and the rabble of Rome. It is said that his plot involved the purpose to kill the consuls, massacre the senators, and to burn the city of Rome. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Cicero delivered in the senate an oration against Catiline, who was present and attempted to reply; but his voice was drowned with the cries of “Traitor.” José Miguel Baños wrote in National Geographic History: The plot called for assassinations and burning the city itself. Widely considered the best orator of his time, Cicero had attempted to warn Rome about Catiline’s treasonous intentions through dramatic speeches in the Senate, but his pleas fell on deaf ears. After the plot had been exposed, Catiline escaped. Five of his conspirators were caught, however, and Cicero advocated for their immediate execution, without trial. Most senators agreed with Cicero, with one major exception—Julius Caesar. He advocated for imprisoning the men, but his recommendation was overturned. [Source José Miguel Baños, National Geographic History, February 26, 2019]

Catiline fled from the senate to his camp in Etruria. Here a desperate battle ensued; and Catiline was defeated and slain, with three thousand of his followers (62 B.C.). Five of his fellow-conspirators were condemned to death by the senate; and Cicero put the judgment into execution. This act afterward exposed Cicero to the charge of executing Roman citizens without a proper trial. But the people hailed Cicero as the savior of Rome, the Father of his Country. The defeat of the Catiline conspiracy was a high mark for Cicero, whom his supporters proudly called pater patriae, father of the fatherland.

Gregory Wakeman wrote in National Geographic History: After the Catiline conspiracy, Cicero was briefly driven into exile because of how he administered justice to members of the coup, in particular killing associates of Catiline without a trial. The conspiracy exposed how extensive poverty and debt was in Roman society, created a climate of paranoia in the Senate, and is ultimately regarded as the first step to the Civil Wars that ended the Roman Republic and built the Roman Empire. In 1969, Robin Seager argued that “Cicero really manufactured the conspiracy and drove Catiline to violence, but his view is not broadly accepted,” adds Saller. [Source Gregory Wakeman, National Geographic History, September 27, 2024]

See Separate Article: JULIUS CAESAR, HIS RISE AS A POLITICIAN, AND CICERO, CATO AND CATILINE europe.factsanddetails.com

Why Catiline Did What He Did

Gregory Wakeman wrote in National Geographic History: Catiline was a patrician from a distinguished family. He had fought alongside Roman general Sulla, helping him win Rome’s first major Civil War, before then rising through the political ranks. In 64 B.C., Catiline stood to become one of Rome’s two consuls. The highest elected public positions in the Roman Republic, the consuls served one-year terms and were elected each year by the Centuriate Assembly. Accused of corruption, Catiline was defeated by Cicero. “Normally, a new man wouldn't win the consulship,” said Josiah Osgood, professor of classics at Georgetown University and a specialist in Roman history.An embarrassed and desperate Catiline ran for consulship again in 63 B.C. “By now he and Cicero were sworn enemies and Cicero did everything he could to stop Catiline,” says Osgood. [Source Gregory Wakeman, National Geographic History, September 27, 2024]

Discovery of the Body of Catiline

“Roman elections were extremely expensive because they were extremely corrupt,” says Edward Watts, professor of history at the University of California, San Diego. “They required you to borrow a lot of money and outlay a lot of cash to try to buy support from people. The idea being you win the consulship, you can then get a command somewhere or govern a province, then make that money back. But if you lose, you're screwed.”

What made these defeats even worse for Catiline is that, in that period, “some older families with a deep history had fallen on hard times,” says Richard Saller, an American classicist and former president of Stanford. “Catiline resented new upstarts like Cicero, who he was having a hard time keeping up with financially.”

With Cicero backed by wealthier Romans that lent out money to make their own income, Catiline adopted a more populist and radical message, insisting that he would cancel debts and relieve the debt crisis. When Catiline lost another election, he retreated to northern Italy, formed an army of veterans from the first Civil War and farmers in debt, and planned to march on Rome so that he could become consul by force. But in January 62, B.C., he was defeated by the Roman Republic in the Battle of Pistoria. Roman historian Sallust would write that “Catiline was despicable, a real menace to the Republic, who represented all that was wrong with Rome” because of his pursuit of demagoguery, says Osgood.

Cicero and the Triumvirate of Caesar, Pompey and Crassus

José Miguel Baños wrote in National Geographic History: Julius Caesar and his patron, Marcus Licinius Crassus, were both formidably rich, and had each used their wealth to gain popular support over the course of their political careers. In the chaos that followed the conspiracy, Julius Caesar and Crassus joined another general, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey, to take control of the government in 60 B.C. Announced when Caesar began his first consulship, the First Triumvirate would rule the republic for six years until the death of Crassus in 53. [Source José Miguel Baños, National Geographic History, February 26, 2019]

At first Cicero refused to support the triumvirate and fled from Rome. In 57, with Pompey’s backing, he returned to the city and tried to persuade Pompey to break his alliance with Caesar. Pompey refused. Cicero begrudgingly gave the triumvirate his approval despite recognizing that the triumvirate was unstable; each of the three men wanted to increase his own power while keeping his two other “allies” in check. No one in the First Triumvirate would be the champion for the republic for whom Cicero hoped.

Disgusted by this turn of events, Cicero left politics for a few years. During this time, he penned some of his most influential works before returning to office in 51 B.C. He accepted the governorship of Cilicia, a province located in present-day Turkey, and then returned to Rome in late 50. Crassus’ death in 53 had increased hostility between Julius Caesar and Pompey, who were headed toward an unavoidable confrontation that would explode into civil war in 49 B.C.

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “The extraordinary coalition, known as the first triumvirate, which came into existence as an informal alliance among Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus in 61/60 B.C., had not been planned as early as a few years before. In 63 B.C. Caesar and Crassus had tried to pass a land bill, the Rullan law, which was violently opposed by Cicero and which went down to defeat; this should probably be viewed as an attempt to head Pompey off, since he was certain to want land for his veterans upon his return from the East. In Pompey's absence, Cicero had drifted as close as possible to the Old Guard; when Pompey returned, it was to them that Cicero led him. Pompey wanted two things: 1) Land for his veterans, and 2) the ratification of his many dispensations over the future status of the lands in the east. Either Pompey was too powerful and popular already, or the conservatives (including M. Porcius Cato) were too pig-headed to see that it was in their own interests to embrace him; in any case he was rebuffed, Cicero could do nothing, and Pompey was driven into the arms of Crassus and Caesar.” [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

First Triumvirate Caesar, Crassus and Pompey

Banishment of Cicero

Clodius, who held the position of tribune, was given the task, first, of keeping hold of the populace; and, next, of getting out of the way as best he could the two most influential men in the senate, Cicero and Cato. The first part of this task he easily accomplished by passing a law that grain should hereafter be distributed to the Roman people free of all expense. To carry out the second part of his task was not so easy—to remove from the senate its chief leaders. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Cato was disposed of, however, by a law annexing Cyprus to the Roman dominion, and appointing him as its governor. Cicero was also got rid of by a law which Clodius succeeded in passing, and which provided that any magistrate who had put a Roman citizen to death without a trial should be banished. Cicero knew that this act was intended for him, and that it referred to his execution of the Catilinian conspirators. After vainly attempting to enlist sympathy in his own behalf, Cicero retired to Greece (58 B.C.) and devoted himself to literary pursuits. With their leaders thus removed, the senate was for a time paralyzed. \~\

Suetonius wrote:“ Marcus Cato, who tried to delay proceedings [by making a speech of several hours' duration; Gell. 4.10.8. The senate arose in a body and escorted Cato to prison, and Caesar was forced to release him], was dragged from the House by a lictor at Caesar's command and taken off to prison. When Lucius Lucullus was somewhat too outspoken in his opposition, he filled him with such fear of malicious prosecution [for his conduct during the Third Mithridatic War] that Lucullus actually fell on his knees before him. Because Cicero, while pleading in court, deplored the state of the times, Caesar transferred the orator's enemy Publius Clodius that very same day from the patricians to the plebeians [59 B.C.], a thing for which Clodius had for a long time been vainly striving; and that too at the ninth hour [That is, after the close of the business day, an indication of the haste with which the adoption was rushed through] Finally taking action against all the opposition in a body, he bribed an informer to declare that he had been egged on by certain men to murder Gnaeus Pompeius , and to come out upon the rostra and name the guilty parties according to a pre-arranged plot. But when the informer had named one or two to no purpose and not without suspicion of double-dealing, Caesar, hopeless of the success of his over-hasty attempt, is supposed to have had him taken off by poison.. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “The 50s B.C. at Rome is the decade of anarchy in the capital at Rome, of gangs and of chaos. Some of the blame for this rests with Pompey, who was notoriously inept at domestic administration, and unfortunately the only of the triumvirs continually present in the city (as his provinces were being governed by proxy). In 58 B.C. the unscrupulous P. Clodius, tool of Caesar and sworn enemy of Cicero (ever since the latter had prosecuted him for an embarrassing youthful peccadillo), was tribune. Among his laws was one directed against poor old Cicero who, inflated with a false sense of his own importance, had foolishly refused to cooperate with the new lords and was thrown to the wolves. Clodius' law (which had to do with the way Cicero had proceeded in the execution of the Catilinarian conspirators) sent the orator into exile. By the summer of 57 B.C. Cicero had decided that maybe he could find it in himself to support Pompey after all, and he was recalled from exile amid great celebrations. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“At this point Cicero still believed that he could play Pompey off against Caesar, and at the same time there was friction between Pompey and Crassus, who had never gotten along very well, so the coalition of the triumvirs looked fragile. A crisis was also brewing over a possible legal challenge to one of the founding acts of the triumvirate, the Lex Julia by which Caesar had settled many of Pompey's veterans in Campania, and also there were the first rumblings of a movement to deprive Caesar of his command in Gaul. Caesar managed to head off disaster by calling the faithful to a conference at Luca in 56 B.C., where the solidarity of the junta was confirmed, giving Caesar some breathing space for the conquest of Gaul. At Luca we hear little of Campania; the focus was on the future status of the triumvirs. Pompey and Crassus were to be consuls again in 55, and Pompey was to get a military command in Spain, while Crassus (who longed to compete with his partners in military honours) was to go to the eastern edge of the Roman empire and defeat the mighty Parthians. It is worth noting that although the Senate was compliant on this occasion (even Cicero supported the new dispositions in a speech which survives titled On the Consular Provinces) the decisions were ratified by the comitia tributa directly, which shows that the trend was towards bypassing the Senate.” ^*^

When Caesar had departed from Rome to undertake his work in Gaul, Clodius began to feel his own importance and to rule with a high hand. The policy of this able and depraved demagogue was evidently to govern Rome with the aid of the mob. He paraded the streets with armed bands, and used his political influence to please the rabble. Pompey as well as the senate became disgusted with the regime of Clodius. They united their influence, and obtained the recall of Cicero from exile. At the same time Cato retuned from his absence in Cyprus. On the return of the old senatorial leaders, it looked as though the senate would once more regain its power, and the triumvirate would go to pieces. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

“Far from undermining Caesar’s confidence, Pompey’s deceitful maneuver only seemed to stiffen his resolve. Throughout that year, the brinkmanship between the two generals grew, and nerves stretched to breaking point. A false rumor spread that Caesar had set out from Gaul with four legions. The statesman and orator Cicero vainly tried to find a peaceful solution to the conflict while a sense that the republic was becoming increasingly ungovernable took hold in the capital. Alliances shifted continually: One of Caesar’s most loyal lieutenants, Labienus, decided to switch sides to Pompey. /*\

Catiline Conspiracy — The Model for Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis

Francis Ford Coppola has been working on his epic sci-fi fantasy drama Megalopolis since the early 1980s. Gregory Wakeman wrote in National Geographic History: Fresh off the success of Apocalypse Now, Coppola became fascinated by the story of Lucius Sergius Catiline, who in 63 B.C. sought to forcibly overthrow the consuls of the Roman Republic, co-led by Marcus Tullius Cicero. This attempted coup d’etat is known as the Catiline conspiracy. Coppola wanted to set the conflict of two ambitious men with very different ideals in modern New York, so that he could draw parallels between the beginning of the end for the Roman Republic and the contemporary United States. [Source Gregory Wakeman, National Geographic History, September 27, 2024]

At a Q&A in New York before the premiere of Megalopolis on September 23, Coppola remarked, “Today, America is Rome, and they’re about to go through the same experience, for the same reasons that Rome lost its republic and ended up with an emperor” Coppola was so adamant about highlighting the similarities between the Roman Empire and U.S. that he named the film’s leading characters after Catiline and Cicero.

With Megalopolis, Coppola focused on Catiline’s ambition to release the lower classes from debt in order to make him a sympathetic figure. In his director’s statement for the film, Coppola explains, “I wondered whether the traditional portrayal of Catiline as ‘evil’ and Cicero as ‘good’ was necessarily true … Since the survivor tells the story, I wondered, what if what Catiline had in mind for his new society was a realignment of those in power and could have even in fact been ‘visionary’ and ‘good’, while Cicero perhaps could have been 'reactionary' and ‘bad’.” Saller acknowledges that accounts of the Catiline conspiracy are “Cicero centric” and “from a historian’s point of view there are reasons to think there are biases.”

Both Watts and Osgood can see some similarities between the late Roman Republic and the current political rhetoric of the U.S. “I think there’s been a significant loss of trust in the integrity of systems,” says Watts. But Saller remains skeptical about such parallels. “The constitutional situation in the U.S. and Rome are very, very different. One of the things that Rome did not have was anything like our Supreme Court. Whatever problems we may think we have with our current Supreme Court, the Roman Republic had no institutional way of resolving differences between leading senatorial generals in their contest for power.” Ultimately, Esposito believes that Megalopolis is a cautionary tale: “There's a line in the movie, ‘Don't let the now destroy the forever.’ That’s such a powerful thought to have right now. The film is a call for hope, for us to think larger than just ourselves.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024