Home | Category: Roman Republic (509 B.C. to 27 B.C.)

SAMNITES

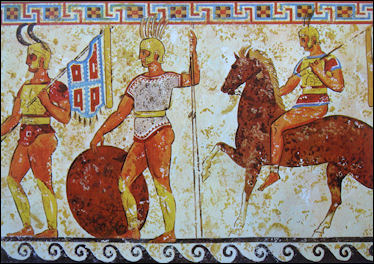

Samnite from a tomb frieze, Nola, 4th century BC The Samnites were rivals of the ancient Romans before the Romans were powerful. Known for their military skill, they were based in the craggy mountains in Abruzzi and Modise and occupied much of southern and central Italy. They were among the last hold outs against the Romans and for a while seemed like the group most likely to dominate Italy. In the 4th century B.C. they controlled Pompeii and other cities. Little is known about them in part because they were one of Rome’s fiercest enemies and the Romans wiped out many reference to them.

The Samnites are better seen as a loosely defined alliance than a tribal group. They spoke an Oscan language and were divided into tribal states. They controlled a large area of southern Italy from 600 to 290 B.C., occupying the area around Pompeii around the 6th century B.C.

Although the Samnites are known mainly as warriors they were also skilled artists. In 2004 a 2300-year-old, yellow tuff sarcophagus was founded in at the remote site of Galita del Capitiano near Sarno and Salerno in southern Italy. Believed to belong to a Samnite warrior, it contained marvelous colored frescos, with shades of blue, red and yellow, depicting scenes of victories and triumphant returns with horsemen, bagpipers and unarmed soldiers.

The Samnites worshiped their own pantheon of gods. Their goddess of love was Mephitis. In June 2004, archaeologists from Italy’s Basilicata University uncovered remains of a Samnite temple dedicated to Mephitis under a Roman temple dedicated to Venus. The archaeologists found offerings to Mephitis and a basin and terra cotta pipes indicating the site of a ritual bath.

The bath and amulets, Emmanuel Curti, chief archaeologist at the site, told the Washington Post indicate the Samnite practice of ritual prostitutions in which young women rich and poor alike, submitted to sex as a site of passage. “To our post-Victorian minds, the practice seems strange. But we can’t look at society through our eyes, Probably the practice became professional at some point. This was, after all, a port city.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Samnium and the Samnites” by E. T. Salmon Amazon.com;

“Ancient Samnium: Settlement, Culture, and Identity between History and Archaeology”

by Rafael Scopacasa (2015) Amazon.com;

“Caudine Forks 321 BC: Rome's Humiliation in the Second Samnite War” by Nic Fields, Seán Ó’Brógáin (Illustrator) Amazon.com;

“Rome's Third Samnite War, 298–290 BC: The Last Stand of the Linen Legion”

by Mike Roberts (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Conquest of Italy” by Jean-Michel David and Antonia Nevill (1996)

Amazon.com

“The Early Roman Expansion into Italy” by Nicola Terrenato (2018) Amazon.com;

“Early Roman Warfare: From the Regal Period to the First Punic War”

by Jeremy Armstrong (2020) Amazon.com;

“Early Roman Armies” (Men-at-Arms) by Nicholas Sekunda, Simon Northwood, Richard Hook (Illustrator) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republic at War: A Compendium of Roman Battles from 498 to 31 BC” by Don Taylor (2017) Amazon.com;

“Armies of the Roman Republic 264–30 BC: History, Organization and Equipment

by Gabriele Esposito (2023) Amazon.com;

“Early Rome to 290 BC: The Beginnings of the City and the Rise of the Republic” by Guy Bradley (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Rise of Rome: From the Iron Age to the Punic Wars” by Kathryn Lomas (2018) Amazon.com;

“A Critical History of Early Rome: From Prehistory to the First Punic War”

by Gary Forsythe (2006) Amazon.com;

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“A Companion to the Roman Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Editor) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Republic” by Isaac Asimov (1966) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republic” by Enthralling History (2022) Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Republic: The Rulers of Ancient Rome From Romulus to Augustus” by Philip Matyszak Amazon.com;

“A History of the Roman Republic” by Cyril E. Robinson (2013) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of the Roman World” by (1981) Amazon.com

“The Romans: From Village to Empire” by Mary T. Boatwright , Daniel J. Gargola, et al. | Feb 26, 2004 Amazon.com;

Samnite Military

Samnite soldiers carried axes, short stabbing swords, spears and shields and wore three-disk corselet armor. They fought in flexible checkerboard formations which made sense for fighting in the mountains and employed guerilla tactics such as lighting quick hit and run attacks that gave their enemies no time to prepare or pursue them. The Samnites were fierce and courageous fighters who often chose to die rather than surrender, leaving thousands dead on the battle field.

The Romans adopted many Samnite tactics. Initially the Romans employed Greek-like phalanx tactics, which were suited more for fighting on plains, against the Samnites in their mountainous homeland and suffered and number of defeats. Later the Romans adopted checkerboard formations — a major military advance for the future rulers of the Western world — and Samnite-style weapons and fared much better.

Archaeological Evidence of the Samnites

Samnite ruins in Aeclanum

Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Because they lived in isolated mountain settlements rather than cities, the pre-Roman Samnite people have been hard to detect in Italy’s archaeological record. A new survey of the vast territory that scholars believe they once inhabited, however, has located an extensive system of Samnite hillforts. University College London archaeologist Giacomo Fontana scoured lidar images covering an area of 5,900 square miles in south-central Italy for traces of ancient ramparts and walls. He then visited nearly 150 sites to document these features on the ground. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

Thus far, Fontana has identified 95 previously unknown hillforts and other types of archaeological sites stretching from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Adriatic Sea, some of which may date to as early as the sixth century B.C. While hillforts along the Adriatic coast appear to have been central meeting places for populations that lived in the surrounding areas, he says, Samnite sites on the Tyrrhenian coast were much smaller and seem to have been occupied seasonally. In the fourth century B.C., the hillforts were central to the Samnites’ resistance to Roman expansion. “Although they were monumental, many of these fortifications were made hurriedly in a period of crisis during the war against Rome,” Fontana says. “Some walls on steep slopes were built directly on top of the bedrock.” By the late third century B.C., the majority of the hillforts had been abandoned as the vanquished Samnites fell under Roman control.

Samnites Versus Rome

Beginning in 343 B.C. the Samnites fought three wars against the Romans. Taking advantage of a moment when the Samnites were busy fighting the Greeks , the Romans invaded their territory and tried to set up colonies near Naples, but the Samnite struck back. At one point Samnite troops trapped a Roman army in a mountain pass and forced it surrender.

The humiliated Roman Senate eventually orchestrated a counterattack. Preparation for renewed war included the construction of the Appian Way, a road that runs south from Rome toward Naples.

The decisive third war between the Samnites and Romans occurred in 295 B.C. when the Romans had taken control of many of the main trade routes in southern Italy and were moving on Samnite territory. The Samnites formed an alliance with Gauls, Etruscans, Umbrians and lesser groups and met the Roman army at Sentinum, near present-day Sassofferrato in the Marches.

The Romans prevailed, in part because they were able to stop the Etruscan and Umbrian troops and prevent them from coming to aid the Samnites. By all accounts the fighting was fierce. Livy recorded 8,700 casualties on the Roman side, the size of Samanite force was not clear. Some scholars have said that around 25,000 people might have died at Sentinum. The Romans were more interested in peace and stability than in occupations and conquest. They signed an alliance with the Samnites that allowed them to rule themselves and maintain autonomy for 200 years.

The Samnites continued to fight after that and were not eliminated as a threat until Roman generals Sulla and Crassus defeated them in 82 B.C. Their reputation remained. Samnite fighting — in which combatants carried large oblong shields, a sword or spear, and was protected by a visored helmet, a greave on the right leg and a protective sleeve on the right arm — was one of the most popular gladiator events.

First Samnite War in Campania (343-341 B.C.)

Samnites and Romans

In extending their territory, the Romans first came into contact with the Samnites, the most warlike people of central Italy. But the first Samnite war was, as we shall see, scarcely more than a prelude to the great Latin war and the conquest of Latium. The people of Samnium had from their mountain home spread to the southwest into the plains of Campania. They had already taken Capua from the Etruscans, and Cumae from the Greeks. Enamored with the soft climate of the plains and the refined manners of the Greeks, the Samnites in Campania had lost their primitive valor, and had become estranged from the old Samnite stock. In a quarrel which broke out between the old Samnites of the mountains and the Campanians, the latter appealed to Rome for help, and promised to become loyal Roman subjects. Although Rome had previously made a treaty with the Samnites, she did not hesitate to break this treaty, professing that she was under greater obligations to her new subjects than to her old allies. In this way began the first contest between Rome and Samnium for supremacy in central Italy—a contest which took place on the plains of Campania. \~\

Battles of Mt. Gaurus and Suessula: Very little is known of the details of this war. According to a tradition, which is not very trustworthy, two Roman armies were sent into the field—the one for the protection of Campania, and the other for the invasion of Samnium. The first army, it is said, met the Samnites at Mt. Gaurus, near Cumae, and gained a decisive victory. The Samnites retreated toward the mountains, and rallied at Suessula, where they were again defeated by the two Roman armies, which had united against them. So brilliant was the success of the Romans that the Carthaginians, it is said, sent to them a congratulatory message and a golden crown. Although these stories may not be entirely true, it is quite certain that the Romans obtained control of the northern part of Campania. \~\

Mutiny of the Roman Legions: This success, however, was marred by a mutiny of the Roman soldiers, who were stationed at Capua for the winter, and who threatened to take possession of the city as a reward for their services. They submitted only on the passage of a solemn law declaring that every soldier should have a just share in the fruits of war, regular pay, and a part of the booty; and that no soldier should be discharged against his will. \~\

Rome withdraws from the War: The discontent of the soldiers in the field soon spread to the Latin allies. The Latins had assisted the Romans and had taken a prominent part in the war; and while the Roman army was in a state of mutiny, they were the chief defenders of Campania against the Samnites. The Campanians, therefore, began to look to the Latins instead of the Romans, for protection; and they too shared in the general defection against Rome. Under these circumstances, Rome saw the need of subduing her own allies before undertaking a war with a foreign enemy. She therefore made a treaty with the Samnites, withdrew from the war, and prepared for the conquest of Latium. \~\

Timeline and Notes on the First Samnite War

fighting in the Samnite war

343-341 B.C.: First Samnite War?

341 B.C.: Treaty between Rome and the Samnites.

[Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

First Samnite War (Livy 7.29-8.2; Diodoros silent) 343-341.

1. Dismissed by some moderns as wholly unhistorical (doublets from 2nd Samnite War).

a. Accepted by Salmon.

b. Motive for invention: justify later harsh treatment of Campania.

2. Begins 343 with appeal to Rome by Capua for help vs. raiding Samnites.

a. Capuans were also Oscan speakers; their quarrel with the Samnites was intramural.

b. But the Samnites were primitive and warlike; Capuans luxurious, sophisticated.

3. A major Q: why did Rome agree to fight the Samnites?

a. Economic motives (Homo)? See intro to Sourcebook # 16.

Terms of the 2nd Carthage treaty (348) indicate Roman economic interests were not very ambitious, or at least not guiding foreign policy:

b. More agressive plebeian military leaders.

c. An agressive alliance of plebeians and patricians (Salmon, 203 ff. )

d. Allowed to speculate on this as example of Roman active imperialism. Why?

e. Ethnic disparity clearly rules out strength in numbers defense.

4. First Samnite War came to little.

a. Rome made separate terms with the Samnites.

b. Capua allied with other Latin cities.

c. That was prelude to widespread Latin revolt beginning in 340.

d. Rome failed to help Samnium vs. Tarentum.

Second Samnite War (326-304 B.C.)

Renewal of the Struggle for Central Italy: The question as to who should be supreme in central Italy, Rome or Samnium, was not yet decided. The first struggle had been interrupted by the Latin war; and a twelve years’ peace followed. The Samnites saw that Rome was becoming stronger and stronger. But they could not prevent this, because they themselves were threatened in the south by a new enemy. Alexander of Epirus, the uncle of Alexander the Great, had invaded Italy to aid the people of Tarentum, and also with the hope of building up a new empire in the West. Rome also regarded Alexander as a possible enemy, and hastened to make a treaty with him against the Samnites. But the death of Alexander left the Tarentines to shift for themselves, and left the Samnites free to use their whole force against Rome in the decisive struggle now to come for the mastery of central Italy. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Cause of the War again in Campania: The direct cause of the second Samnite war, like that of the first, grew out of troubles in Campania. Here were situated the twin cities of Palaepolis (the old city) and Neapolis (the new city), which were still in the hands of the Greeks, but under the protection of the Samnites. Many disputes arose between the people of these cities and the Roman settlers in Campania. Palaepolis appealed to the Samnites for help, and a strong garrison was given to it. The Romans demanded that this garrison should be withdrawn. The Samnites refused. The Romans then declared war and laid siege to Palaepolis, which was soon captured by Q. Publilius Philo. \~\

Greek helmet found in many Samnite graves

Battle at the Caudine Forks (321 B.C.): In the early part of the war the Romans were nearly everywhere successful. They formed alliances with the Apulians and Lucanians on the south, and they also took the strong city of Luceria in Apulia; so that the Samnites were surrounded by the Roman army and their allies. But in spite of these successes, the great Samnite general, Pontius, inflicted upon the Romans one of the most humiliating defeats that they ever suffered. The Roman consuls in Campania, deceived by the false report that Luceria was besieged by the whole Samnite force, decided to hasten to its relief by going directly through the heart of the Samnite territory. In passing through a defile in the mountains near Caudium, called the “Caudine Forks,” the whole Roman force was entrapped by Pontius and obliged to surrender. The army was compelled to pass under the yoke; and the consuls were forced to make a treaty, yielding up all the territory conquered from the Samnites. But the Roman senate refused to ratify this treaty, and delivered up the offending consuls to the Samnites. Pontius, however, refused to accept the consuls as a compensation for the broken treaty; and demanded that the treaty should be kept, or else that the whole Roman army should be returned to the Caudine Forks, where they had surrendered. Rome refused to do either, and the war was continued. \~\

Uprising of the Etruscans: After breaking this treaty and recovering her army, Rome looked forward to immediate success. But in this she was disappointed. Everything seemed now turning against her. The cities in Campania revolted, the Samnites conquered Luceria in Apulia and Fregellae on the Liris, and gained an important victory in the south of Latium near Anxur. To add to her troubles, the Etruscans came to the aid of the Samnites and attacked the Roman garrison at Sutrium. The hostile attitude of the Etruscans aroused Rome to new vigor. Under the leadership of Q. Fabius Maximus Rullianus, the tide was turned in her favor. Many victories were gained over the Etruscans, closing with the decisive battle at Lake Vadimonis, and the submission of Etruria to Rome.

Capture of Bovianum and End of the War: Rome now made desperate efforts to recover her losses in the south. Under the consul L. Papirius Cursor, who was afterward appointed dictator, the Romans recaptured Luceria and Fregellae. The Samnites were defeated at Capua and driven out of Campania. The war was then carried into Samnium, and her chief city, Bovianum, was captured. This destroyed the last hope of the Samnites. They sued for peace and were obliged to give up all their conquests and to enter into an alliance with Rome. \~\

Timeline and Notes on the Second Samnite War

326-304 B.C.: Second Samnite War.

311-304 B.C.: War with the Etruscans.

310 B.C.: Roman victory at Ciminian Hills takes heart out of Etruscan rebellion.

311 B.C.: Roman Navy nascent (duoviri navales).

306 B.C.: Bogus third treaty between Rome and Carthage (Livy 9.43).

304 B.C.: Roman victory at Bovianum Vetus in Samnium.

[Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

Second Samnite War 326-304

1. Ignited after Neapolis was taken by the Samnites, retaken by Rome at Capua's behest in 327.

a. Capuan exiles at Neapolis suburb (Palaipolis) had invited the Samnites in.

2. Rome had already signalled hostility to Samnium by allying with Tarentum.

a. Rome had founded Fregellae in Campania in 328 (Livy 8. 22).

b. It was an affront to the Samnites bcse it looked like a fortress against incursions into Campania.

3. In 321. Rome tried to attack Samnium directly from Capua across the Apennines. Livy 9.1

- The Caudine Forks. No battle, just a surrender by the Romans.

a. Livy says the Romans were lured towards Luceria by false reports of a Samnite attack there.

b. An agreement was made by the consuls under duress on the spot.

c. Livy has Rome immediately repudiate the treaty and continue fighting.

d. Actually the peace lasted, 321-316; Samnites got Fregellae.

e. Later (316) the Romans would claim it was not valid (source of Livian version).

1. Probably because it was not concluded with proper ceremonies.

6. Rome restarted the war by colonizing Luceria (Livy 9.26) and seizing Satricum.

7. Another setback followed in 314 with the Roman defeat at Lautulae in 315.

a. Livy (9.23) turns it into a Roman victory; prefer Diodoros (19.72.8).

b. Capua defects. Livy reports it as a plot by Capuan nobles.

Battle of the Cuadine Forks in the Samnite Wars

c. Major Roman victory at Caudium (Livy 9.27), Campania is quickly secured.

d. Via Appia links up Rome and Capua. (312-244)

1. When finally completed in 244 it went south all the way to Tarentum.

7. Samnites ally with Etruscans, plus Marsi, Hernici, Paeligni.

a. But the Etruscans suffer a major defeat almost immediately (Ciminian Hills, 310).

b. One by one the allies of the Samnites drop away and make separate peaces with Rome.

c. War ends with Samnite defeat at Bovianum Vetus in 304?

d. Possibly a Livian invention (9. 44). Treaty of 341 (Livy 8.2) was renewed.

Striking thing about the Second Samnite War

a. Steadfast support of the Latin League. Best proof that this is not product of an imperialist policy.

Third Samnite War(298-290 B.C.)

The Italian Coalition against Rome: Although Rome was successful in the previous war, it required one more conflict to secure her supremacy in central Italy. This war is known as the third Samnite war, but it was in fact a war between Rome and the principal nations of Italy—the Samnites, the Umbrians, the Etruscans, and the Gauls. The Italians saw that either Rome must be subdued, or else all Italy would be ruled by the city on the Tiber. This was really a war for Italian independence. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Cause of the War in Lucania: Rome and Samnium both saw the need of strengthening themselves for the coming conflict. Rome could depend upon the Latins, the Volscians, and the Campanians in the south. She also brought under her power the Aequians and the Marsians on the east. So that all her forces were compact and well in hand. The Samnites, on the contrary, were obliged to depend upon forces which were scattered from one end of the peninsula to the other. They determined first to win over to their side the Lucanians, who were their nearest neighbors on the south, but who had been the allies of Rome in the previous war. This attempt of the Samnites to get control of Lucania led to the declaration of war by Rome. \~\

The War carried into Etruria: The Samnites now made the most heroic efforts to destroy their hated rival. Three armies were placed in the field, one to defend Samnium, one to invade Campania, and the third to march into Etruria. This last army was expected to join the Umbrians, the Etruscans, and the Gauls, and to attack Rome from the north. This was a bold plan, and alarmed the city. Business was stopped, and all Roman citizens were called to arms. The Roman forces moved into Etruria under the consuls Q. Fabius Rullianus and Decius Mus, the son of the hero who sacrificed himself in the battle at Mt. Vesuvius. The hostile armies were soon scattered, and the Samnites and Gauls retreated across the Apennines to Sentinum (map, p. 81). \~\

Battle of Sentinum (295 B.C.): Upon the famous field of Sentinum was decided the fate of Italy. Fabius was opposed to the Samnites on the right wing; and Decius Mus was opposed to the Gauls on the left. Fabius held his ground; but-the Roman left wing under Decius was driven back by the terrible charge of the Gallic war chariots. Decius, remembering his father’s example, devoted himself to death, and the Roman line was restored. The battle was finally decided in favor of the Romans; and the hope of a united Italy under the leadership of Samnium was destroyed. \~\

Samnite-style gladiator armor

End of the Italian Coalition: After the great battle of Sentinum, the Gauls dispersed; Umbria ceased its resistance; and the Etruscans made their peace in the following year. But the Samnites continued the hopeless struggle in their own land. They were at last compelled to submit to Curius Dentatus, and to make peace with Rome. Another attempt to form a coalition against Rome, led by the Lucanians, failed; and Rome was left to organize her new possessions. \~\

Notes on the Third Samnite War (298-290 B.C.)

1. Samnites seize opportunity of Roman distraction with the Gauls (Senones).

a. Hence the major battles of this war take place in Umbria.

2. Latin colony at Narnia (299 B.C.) was intended as outpost against Gallic incursions.

3. Samnites invade Lucania; Rome agrees to help (no prior commitments in this region).

4. Defeat of Romans under L. Scipio Barbatus at Camerinum in Southern Umbria.

4. Turning point is Roman victory at Sentinum in northern Umbria, 295 B.C.. (Livy 10. 27-30)

a. Occasion of the devotio of Decimus Mus, repeating the deed of his father in 340.

b. note Gauls and Samnites fighting together at this battle.

5. Samnites fight on, but are on the defensive in Samnium until 291 B.C..

a. They were forced to accept "allied" status.

6. This still does not look like a Roman war of aggression.

[Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

Results of the Samnite Wars

Rome’s Position in Central Italy: The great result of the Samnite wars was to give Rome the controlling position in central Italy. The Samnites were allowed to retain their own territory and their political independence. But they were compelled to give up all disputed land, and to become the subject allies of Rome. The Samnites were a brave people and fought many desperate battles; but they lacked the organizing skill and resources of the Romans. In this great struggle for supremacy Rome succeeded on account of her persistence and her great fortitude in times of danger and disaster; but more than all else, on account of her wonderful ability to unite the forces under her control. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Increase of the Roman Territory: As a result of these wars, the Roman territory was extended in two directions. On the west side of the peninsula, the greater part of Campania was brought into the Roman domain; and the Lucanians became the subject allies of Rome. On the east side the Sabines were incorporated with Rome, receiving the partial right of citizenship, which in a few years was extended to full citizenship. Umbria was also subdued. The Roman domain now stretched across the Italian peninsula from sea to sea. The inhabitants of Picenum and Apulia also became subject allies. \~\

Manius Curius Dentatus and the Samnite Ambassadors

The New Colonies: In accordance with her usual policy, Rome secured herself by the establishment of new colonies. Two of these were established on the west side—one at Minturnae at the month of the Liris River, and the other at Sinuessa in Campania (map, p. 80). In the south a colony was placed at Venusia, which was the most powerful garrison that Rome had ever established, up to this time. It was made up of twenty thousand Latin citizens, and was so situated as to cut off the connection between Samnium and Tarentum. \~\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024