Home | Category: Early Settlements and Signs of Civilization in Europe / Bronze Age Europe

NEOLITHIC AND BRONZE AGE FRANCE

Archeological cultures from the Neolithic period (5000 to 2000 B.C.) in France include the the Linear Pottery culture (c. 5500 – c. 4500 B.C.), the Rössen culture (c. 4500—4000 B.C.), and the Chasséen culture (4,500 - 3,500 B.C.; named after Chassey-le-Camp in Saône-et-Loire). The latter is the name given to the late Neolithic pre-Beaker culture that spread throughout the plains and plateaux of France, including the Seine basin and the upper Loire valleys. The 'Armorican' (Castellic culture) and Northern French Neolithic (Cerny culture) is based on traditions of the Linear Pottery culture or "Limburg pottery" in association with the La Hoguette/Cardial culture. [Source: Wikipedia]

Most of the the megalithic (large stone) monuments in France, such as the dolmens, menhirs, stone circles and chamber tombs, date to the Neolithic period. These are found throughout France but are most numerous in the Brittany and Auvergne regions. The most famous of these are the Carnac stones, which are at least 5300 years old and may be 6500 years old, and the stones at Saint-Sulpice-de-Faleyrens.

The Bell Beaker culture (c. 2800–1900 B.C.) was a fixture of Copper Age France. It expanded over most of France, excluding the Massif Central. The Bell Beaker is named after the inverted-bell beaker drinking vessel used at the very beginning of the European Bronze Age, arising from around 2800 BC. The Bell Beaker culture was present in Britain from c. 2450 B.C., and was characterized by single burial graves.

The Bronze Age (2000-700 B.C.) archeological cultures in France include the transitional Beaker culture (c. 2800–1900 B.C.), the Early Bronze Age Rhône culture (c. 2300-1600 B.C.) and Armorican Tumulus culture (c. 2200 – c. 1400 B.C.), the Middle Bronze Age Tumulus culture (c. 1600-1200 B.C.), and the Late Bronze Age Atlantic Bronze Age (c. 1300 – c. 700 B.C.) and Urnfield culture (c. 1300-800 B.C.). Early Bronze Age sites in Brittany (Armorican Tumulus culture) are believed to have grown out of the Beaker Culture.

Is France the home of the first veterinarian surgery. According to Archaeology magazine: A hole in a 5,200-year-old cow skull is evidence of Neolithic bovine brain surgery. When the cranium was originally found at Champ-Durand, France, it was thought that the hole was caused by another cow’s horns, but reanalysis confirmed that the aperture’s characteristics are more consistent with trepanation. Experts believe that perhaps the world’s first known veterinarian attempted to save the cow’s life through surgery, or that Neolithic surgeons honed their skills on domestic animals before applying them to human subjects. [Source: Archaeology magazine, July- August 2018]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Key to Northwest European Origins” by Raymond F McNair (2012) Amazon.com;

“Neolithic Houses in Northwest Europe and beyond” by Timothy Darvill and Julian Thomas (2002) Amazon.com;

“Neolithic Enclosures in Atlantic Northwest Europe” by Timothy Darvill and Julian Thomas (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ancient France: Neolithic Societies and Their Landscapes 6000-2000BC”

by Christopher Scarre and Glyn Daniel (1984) Amazon.com;

“Farm, Hunt, Feast, Celebrate: Animals and Society in Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Age Northern France” by Dr. Ginette Auxiette and Dr. Lamys Hachem (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Megaliths of Brittany” by Jacques Briard (1991) Amazon.com;

“Carnac, The Alignments: When Art and Science were One” by Howard Crowhurst (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Megaliths of Northern Europe” by Magdalena S. Midgley (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Significance of Monuments” by Richard Bradley (1998) Amazon.com;

Monumentalising Life in the Neolithic: Narratives of Continuity and Change

by Anne Birgitte Gebaer, Lasse Sørensen, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“Megalith: Studies in Stone” (Wooden Books) (2019) Amazon.com;

“Magic Stones: The Secret World of Ancient Megaliths” by Jan Pohribny (2007) Amazon.com;

“Megaliths” by David Corio and Lai Ngan Corio (2003) Amazon.com;

“Megaliths and Their Mysteries: A Guide to the Standing Stones of Europe”

by Alastair Service, Jean Bradbery Amazon.com;

“The World of Stonehenge” by Duncan Garrow (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Stonehenge People: An Exploration of Life in Neolithic Britain 4700-2000 BC”

by Rodney Castleden (2002) Amazon.com;

“Megaliths of the World” by Luc Laporte, Jean-marc Large, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Old Stones: A Field Guide to the Megalithic Sites of Britain and Ireland” by Andy Burnham (2018) Amazon.com;

“Stonescapes: A Field Guide to Sacred Stones of Ireland and Scotland” by Aaron B. Christian PhD (2025) Amazon.com;

“Megaliths, Myths and Men: An Introduction to Astro-Archaeology” by Peter Lancaster Brown (2000) Amazon.com;

“Malta & Gozo A Megalithic Journey” by Neil McDonald (2016) Amazon.com;

“Malta: The Temple Builders” by Linda C. Eneix (2025) Amazon.com;

“Malta: an Archaeological Guide” by David H Trump (1971) Amazon.com;

“Malta: Its Archaeology and History” by John Samut Tagliaferro (2000) Amazon.com;

Dozens of Burials and 'Sacrificed' Urns at a 8,000-Year-Old Site in France

Archaeologists in France have excavated a Neolithic site containing 63 burials and hundreds of structures and artifacts that was occupied by humans for roughly 4,000 years, beginning around 8,000 years ago. The site in Clermont-Ferrand, a city in the Auvergne region of central France, was discovered during construction work in the 1980s. However, it wasn't until a highway-widening project that started in 2019 that archaeologists began excavations there, according to France's National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP). [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, March 19, 2024]

Jennifer Nalewicki wrote in Live Science: Radiocarbon dating revealed that humans visited the area before 6000 B.C., during the Mesolithic, or Middle Stone Age. But the vast majority of the radiocarbon dating showed that the site was used throughout much of the Neolithic period, also known as the New Stone Age. During this time, people began creating settlements and relying on agriculture; some of the site's ceramics, hearths and dug pits date to between 4750 and 4500 B.C.

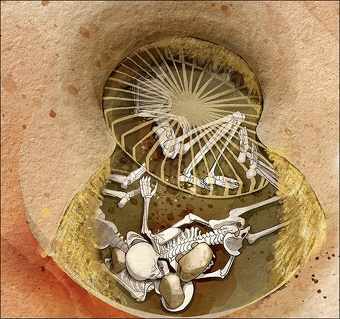

Archaeologists also discovered a variety of tombs, mostly consisting of "simple pit burials" with no furnishings. In these pits, the deceased were buried in a "folded position," lying on their sides with their knees bent. However, researchers found several tombs built out of dry stone (stacked stones with no mortar) that were likely covered with earthen mounds. These tombs contain "complex arrangements, sometimes accommodating several individuals," and date to the fifth millennium B.C., according to the statement.

The team also found cists, or graves made from long rock slabs. It appears that people no longer lived at the site by this time but rather used it as a burial ground. By the fourth millennium B.C., the practice of cremation had been introduced, as revealed in two separate tombs with cremated deposits. People also moved back to the site, according to radiocarbon dating of domestic structures from this time. Human and animal burials continued until the beginning of the second millennium B.C., with excavations yielding several silos containing the remains of sacrificed cattle.

In addition to the dozens of burials, archaeologists unearthed numerous ancient artifacts. These included a "rare object" made using a polished piece of deer antler that was prominently placed on a human skull, intentionally broken or "sacrificed" spherical funeral urns, ceramic containers, a wild boar tusk that may have been worn as a bracelet, and a flint arrowhead. The team also found a roughly 3,300-year-old perforated, double-headed ax "of exceptional workmanship." It was carved out of a metamorphic rock known as serpentinite, which had been "deliberately broken" into three pieces, according to the statement. The excavations show that the site had a "long Neolithic occupation," with gaps in occupancy and changing burial customs. "Funerary practices and gestures show a wide variety, which will need to be analyzed in detail to retrace the history of this emblematic site of Neolithic Auvergne," the team said in the statement

Using DNA to Put Together a Large 7,000-Year-Old Family Tree in France

In a study published July 26, 2023 in the journal Nature, a team of scientists used roughly 7,000 year-old DNA to reconstruct two massive family trees of people that lived in the Paris Basin region in northern France and combine that with information gleaned by the way burials are organized. Their findings suggest that some females left their home community to join another. It also provides evidence of stable health conditions and a supportive social network within one prehistoric community in Europe.[Source: Laura Baisas, Popular Science, July 27, 2023]

Laura Baisas wrote in in Popular Science: In this new study, the team used ancient genome-wide data excavated from Gurgy, Les Noisats, a large Neolithic funerary sites between 2004 and 2007. The remains of 94 individuals buried in Gurgy are dated to approximately 4,850 to 4,500 B.C.. The team combined this ancient genome data with strontium isotope analysis, mitochondrial DNA to show maternal lineages, and Y-chromosome data for patrilineal lineages, age-at-death, and genetic sex to build two family trees.

The first tree connects 64 individuals over seven generations, and is the largest pedigree reconstructed from ancient DNA to date. The second family tree connects 12 individuals over five generations.“Since the beginning of the excavation, we found evidence of a complete control of the funerary space and only very few overlapping burials, which felt like the site was managed by a group of closely related individuals, or at least by people who knew who was buried where,” study co-author and University of Bordeaux archaeo-anthropologist Stéphane Rottier said in a statement.

The team also found a positive correlation between spatial and genetic distances of the remains, which indicates that the deceased were likely to be buried close to a relative. When examining the pedigrees further, they also saw a strong pattern along paternal lines. Each generation, it seems, is almost exclusively linked to the generation before through the biological father. The entire Gurgy group can be connected through the paternal line.

Women Often Came from Outside the Community in 7000-Year-old France

Laura Baisas wrote in Popular Science: On the other side of the family trees, evidence from mitochondrial lineages and the strontium stable isotopes show a non-local origin of most of the women. This suggests Gurgy had a practice called patrilocality, where sons stayed where they were born and then had children with women from outside of the community. By contrast, most of the lineage of adult daughters are missing, suggesting there might have been a reciprocal exchange system with other communities. The newer female individuals were only very distantly related to each other, which shows that they likely came from a network of communities nearby instead of just one group. There could have been a relatively large exchange network of many groups in the region. [Source: Laura Baisas, Popular Science, July 27, 2023]

“We observe a large number of full siblings who have reached reproductive age. Combined with the expected equal number of females and significant number of deceased infants, this indicates large family sizes, a high fertility rate and generally stable conditions of health and nutrition, which is quite striking for such ancient times,” study co-author and Ghent University paleogeneticist Maïté Rivollat said in a statement.

Additionally, the team could point to one male individual from which everyone in the largest family tree was descended. This “founding father” of the cemetery has a unique burial, with skeletal remains buried as a secondary deposit inside the grave pit of a woman. This indicates that his bones must have been brought from where he originally died to be reburied at Gurgy.

“He must have represented a person of great significance for the founders of the Gurgy site to be brought there after a primary burial somewhere else,” co-author and University of Bordeaux paleogeneticist Marie-France Deguilloux said in a statement.

While the main pedigree spans seven generations, the demographic profile suggests that a Gurgy itself was probably only used for three to four generations, or approximately one century. Nevertheless, these lengthy pedigrees represent a step forward in our understanding of the social organization of past societies.

“Only with the major advances in our field in very recent years and the full integration of context data it was possible to carry out such an extraordinary study,” study co-author and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology molecular anthropologist Wolfgang Haak said in a statement. “It is a dream come true for every anthropologist and archaeologist and opens up a new avenue for the study of the ancient human past.”

5,500 Years Ago, Women Were Tied Up and Killed Mafia-Style in France

More than 5,500 years ago, two women were tied up and probably buried alive — a form of killing associated with the Italian Mafia — in a ritual sacrifice according to an analysis of skeletons discovered at an archaeological site in southwest France. Issy Ronald of CNN wrote: Researchers investigated the unusual position of three female skeletons found in 1985 at the site in the town of Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux, and concluded that two of the women probably died from a form of torture known as “incaprettamento,” which involves tying a person’s throat and ankles so that they eventually strangle themselves due to the position of their legs. [Source: Issy Ronald, CNN, April 17, 2024]

The researchers also reviewed skeletons found at other archaeological sites across Europe and identified 20 other probable instances of similar sacrificial killings. The practice may have been relatively widespread in Neolithic, or late Stone Age, Europe, according to the study, published in April 2024 in the journal Science Advances The third woman found at the site was in a normal burial position and “we don’t know how she died,” Éric Crubézy, one of the paper’s lead authors and a biological anthropologist at Paul Sabatier University in Toulouse, told CNN “But we can say that they put the three women in the grave at the same time.”

The women’s burial place was aligned with the sunrise at summer solstice and sunset at winter solstice, leading the study’s authors to hypothesize that this site acted as somewhere people gathered to mark the turning of the seasons, which may have involved human sacrifices. “There is always this idea that somebody is dying and that the crops will grow,” Crubézy added, referencing that belief appearing in other cultures such as the Inca practice of human sacrifice in South America.

The three skeletons were buried in a grave built in the style of a silo, where grain is typically stored, inside a wooden structure and surrounded by a trench. At the other sites across Europe, men and children as well as women were also found sacrificed in this way, the study said. Though it is impossible to prove definitively that the women in the grave at Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux died in situ, their position “stacked atop each other and entwined with fragments of grindstones” implies that they were placed there forcefully and deliberately, “strongly suggesting that their demise likely occurred” in the grave, the study said.

6000-Year-Old Settlements in France

In February 2023, archaeologists said they made a “breakthrough,” in determining where the “first megalith builders” in France came from according to a study published in Antiquity. The Miami Herald reported: The researchers studied Le Peu, a site over 6,000 years old and located only a few miles away from the megalithic cemetery of Tusson Tusson cemetery, which has five long burial mounds and is “among the most imposing known in Europe.” To study Le Peu, researchers conducted an aerial survey of the area, identifying the site’s overall arrangement. Next, the team did a geomagnetic survey to reveal details of the site. On these surveys, the researchers noticed a ditch running along the one edge, four rectangular buildings and two “crab claw” entrances extending outward. The unusual entrances and the rectangular buildings were “unique” and otherwise “completely unknown” structures for this region of France during the fifth millennium B.C., the researchers wrote. To investigate further, the team excavated portions of the site, unearthing bones, ceramics, pits and hearths. The details of Le Peu’s “monumental” and “fortified” settlement began to take shape.[Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, March 8, 2023]

Le Peu was constructed in the middle of a horseshoe-shaped marsh. A double-layered, wooden wall ran around the entire site. On two sides, the enclosure wall had “crab claw”-shaped entrances positioned at strategic protection points. The entrances “accentuate the monumentality of the enclosure,” the authors wrote. The depth of the entrance remains indicates the structures were probably tall. ”Massive” stones were packed around these dramatic structures. Inside the enclosure, archaeologists uncovered the remains of four similar-sized rectangular buildings. One building had traces of smaller posts inside, suggesting a raised platform that could have served as a cooking or sleeping area. Another building had an “unusual” square shape.. These buildings are the “oldest rectangular building known in west-central France.”

The Le Peu settlement was destroyed by fire around 4400 B.C. The settlement’s ruins date to the same period as the nearby Tusson cemetery site, indicating the megalithic cemetery’s builders could have lived at Le Peu. This, however, is “impossible” to know for certain. The Le Peu settlement reveals the development of two forms of monumental architecture in the mid-fifth millennium B.C.: wooden “enclosure for the living and megalithic tombs for the dead,” the authors wrote.

On a different site, in Corsica, the Miami Herald reported: The site in Sotta contains two distinct settlements, according to an April 24, 2023 news release from the Institut national de recherches archéologiques préventives (INRAP). The first settlement is partially preserved while the second is well preserved. The first settlement — which dates to about 6,000 years ago held a stone structure filled with remains of an obsidian knapping workshop. Within the workshop, there is evidence indicating that ancient people used a variety of methods to make obsidian tools. [Source: Moira Ritter, Miami Herald, April 28, 2023]

The second settlement — which dates to the third millennium B.C., about 4,000-5,000 years ago — was better preserved. Archaeologists uncovered a system of terraces full of remains of occupation and activities. The terraces were topped with an approximately 3-foot tall or fortified wall made of granite blocks, according to researchers. On the first terrace below it was a stone arc also made from granite blocks. The building techniques used in the arc indicate it was used as some kind of roof, but experts are investigating its exact purpose.

Within the terraced structure, there was also a corridor and staircase that appeared to function as a passageway to the upper level of the system. Within the corridor, several vases were unearthed. Two other similar but more refined terraced systems were discovered at the site, according to the team. It is still unclear what the purpose of these structures was, but archaeologists say they could have been used for food storage, metallurgy or other artisan activities.

The Neolithic site, and the terraced section especially, held thousands of unusual copper and other metal artifacts, according to archaeologists. Some remains indicated traces of melting that took place at the site. There were also cattle teeth and rare cranial skeletal remains that seemed to have been burned,. Other artifacts gave experts greater insight into life during the Neolithic era and at the settlement in particular. Among the smaller remains were artifacts indicating artisan practices in daily life such as flints, obsidian, quartz, arrowheads, polishers, axes, wheels and tools. Further studies into each piece are ongoing and will hopefully give a greater view into ancient life.

Megaliths, Dolmen and Tumulus

Megaliths are large stone structures (“mega” means "large" and "lithos" means “ stone”). There are many places in Europe with megaliths. Megalithic structures have been found from Morocco in the south to Sweden in the north, Stonehenge in England is probably the best known. Sweden and Germany have their own "Stonehenges. Larger "megalithic" structures are found elsewhere — such as at Carnac in France's Brittany region, where there are more than 10,000 menhirs aligned in rows. There are so many of many megaliths in Carnac that many of the English words used to describe them come from Breton, the language of Britanny.

There are different words to describe how the stones are arranged. A “ dolmen” is a stone table that is used to identify a group burial chambers, or "houses of the dead." It consists of upright stones capped with a slab of stone for a roof. Two walls side by side, with a cap stone are known as cromleches. There are several of these at Stonehenge. A “ tumulus” is a large earthen burial mound. A “ cairn” is a pile of rocks. And the huge standing stones themselves are called “ menhirs”. The word "Menhir" is possibly derived from a Celtic word for "stone". When the stones are arranged into a large circle this is called a “ cromlech” .

Brittany Alignment Menec Megaliths built in Spain, France, the Baltic , Iceland and Britain were independently erected by ancient farming people.

Scattered around the large Italian island of Sardinia are about 7000 ancient standing stones and cone towers including the "The Tomb of the Giants" and the "Houses of the Witches." The tombs are carved into the rock and some of the cone towers — originally 13 meters (40 feet) in diameter and up to 20 meters (65 feet) high — were used as dwellings.

The people who built megaliths seem to have had similar beliefs about the sun and astronomy. Many megaliths seem to be aligned with certain astronomical events such as the midwinter or midsummer sunrise. This is the case with Stonehenge. "There are differences as well, but one common element is the sun," Leonardo García Sanjuán, an archaeologist at the University of Seville, told Live Science. "The sun was at the center of the worldview of these people." [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, May 15, 2023]

According to Live Science: Archaeologists suspect that the practice of building megalithic monuments spread over Europe during the Neolithic with successive waves of settlers, perhaps farmers from the Near East, who seem to have assimilated the indigenous hunter-gather peoples, according to a 2003 study in the journal Annual Review of Anthropology. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, August 31, 2022]

See Separate Articles ORKNEY ISLANDS: THE HOME OF BRITAINS GREAT NEOLITHIC CULTURE europe.factsanddetails.com STONEHENGE: ITS STONES AND BUILDERS, THEORIES ON ITS PURPOSE, AND STRUCTURES RELATED TO IT europe.factsanddetails.com

Good Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Livescience livescience.com/

Megaliths in France

There are so many megaliths around Carnac in Brittany that many of the English words used to describe them — such as dolmen, — come from the Breton language of Brittany. But Brittany isn't the only place in France with megaliths.

According to archaeology magazine: Roadwork at Veyre-Monton in central France has revealed the first known megalithic site in the region. There, archaeologists from France’s National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) have uncovered evidence of cult activity spanning thousands of years, from the Neolithic period through the Bronze Age. They identified 30 menhirs, or monoliths, arranged from largest to smallest in a 500-foot-long line oriented precisely north to south. Most of the menhirs are made of local basalt and undecorated, but a single limestone example was sculpted to resemble a person, with two small breasts and an engraved chevron that might depict forearms. [Source: Benjamin L eonard, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2019]

“At some point all the menhirs were intentionally buried, as was an adjacent four-sided stone cairn, measuring 46 feet long and 21 feet wide, that surrounded the tomb of a tall man. Despite the site’s long use, the motivations behind the monuments’ removal from the landscape are unknown. “It’s very tempting to interpret this as the result of a change in beliefs,” says INRAP archaeologist Ivy Thomson, “but it may also be linked to the disgrace of the community in control of the site, or even something more trivial.”

Megaliths of Carnac in Brittany, France

Carnac Kermario Dolmen The oldest stone structures in Europe are the Megaliths of Carnac on the southwest coast of Brittany. Here approximately 10,000 megaliths (Stonehedge-like "great stones") have been raised among what are now maritime fields, farms, cottages, and heath more or less in single parallel rows. The British writer and archeologist Evan Hadingham described them as "one of archeology's greatest mysteries...it poses as many tantalizing unanswered questions as the pyramids." [Source: William Devenport, National Geographic, June 1978, Robert Wernick, Smithsonian magazine; New York Times travel article; French Government Tourism Office]

Covering an area of roughly five square miles, Carnac contains the world's largest assemblage of prehistoric stone monuments. About 3,000 stones (out of a possible 10,000 original stones) are grouped in three alignments concentrated in a small area north of the town of Carnac. The largest megaliths (now broken) are 65 feet high and weigh almost 400 tons. Among the items unearthed by archaeologists at the site are beads, tools, and jadite axes. There are so many of these stones around Carnac that the English words used to describe them all come from the Breton language. (See Above)

Most of the stones are arranged into three major groupings know as alignments that consists of huge stones fanning out in rows from a cromlech. Similar groupings of stone have been found in northern Scotland and the Exmoor and Dartmoor areas of southwestern England. The U-shaped cromlechs in Carnac and Caithness, Scotland have the same astronomical sight lines even though they are 750 miles a part.

The alignments of standing stones in Carnac is roughly northeast to southwest. Many of the stones are relatively small, only a few feet high. The largest complete ones are about 15 feet high. The most impressive stones are fenced off; they have to be observed from a road or a pathway.

History Megaliths of Carnac

Brittany Kerloa Menhir There was no mention of the stones of Carnac before the 18th century. The first known account is by travelers who wrote about them in the 1720s. The 19th century novelist Gustave Flaubert wrote, "Carnac has more rubbish written about it than it has standing stones."

Most of the stones were raised between 4000 and 4500 B.C. (2000 years before Stonehedge) As is true with Stonhedge nobody is sure why they were placed where they were. There are several local legends that account for their origin. Some say they were they were produced by goblins, Druids or Merlin the magician. Other say they were Roman soldiers turned to stone while chasing after local holymen. Yet others say they were local soldiers so determined to stand their ground against the Romans they turned to stone. Most historians believe the stones were a astronomical calendar used to determine lunar eclipses, solar cycles, harvests, planting times, religious festivals, and fertility rites. Many of the stones are lined up so they correspond with the sunrises and sunsets of specific dates. Others have objects buried around them which indicate they may have been used in fertility and funerary rituals.

Other archeologist have suggested they may have been representations of snakes, fish-drying platforms, phallic symbols, representations of cattle, signs for hotels and markets, windbreaks for tents, fields for ancient sports or games or markers showing the routes to local brothels. Some modern pseudo-scientists claim they are "stone computers" built by to guide alien spacecraft.

The stones were taken from local quarries. They may have been prodded loose using water-soaked wedges placed into cracks that widened in fractures rock. It is believed they were moved using rollers, levers, inclined planes, ropes and pulleys. By one estimate at least 200 people were needed to drag a 32-ton slab on wooden rollers on level ground.

Archeologist originally thought that the people who raised the megaliths were descendants of peoples that came from ancient Egypt, Greece or Crete based on similarities between certain symbols and artistic motifs found in those places and in Carnac. In the 1950s and 1960s when carbon dating dated tombs in the area to between 4300 and 4650 B.C., the archeologist were shocked by their age. Assumptions made about early people in Europe and the Mediterranean were turned completely on their head. If anything it was the people of Breton that influenced ancient Egypt, Greece or Crete.

From what archaeologist can tell the people who built the stone monuments were farmers who raised cattle and crops on farmsteads which had standing stones or stone rows on them. These people are believed to have arrived in Brittany around 5500 B.C. Their successors are believed have been from a succession of cultures with their own myths and rituals.

People in some part of Brittany conduct ceremonies at some of the stones. At Cruz-Moquen, women hoping to get pregnant raise their skirts to a dolem during the full moons. At a menhir called Le Vaisseau in Le Ménec, childless couples fling off their clothes on the full moon and run around the stone in hopes of having a child.

Important Megaliths of Carnac

Brittany Menec West Menec Alignment contains 1099 granite menhirs arranged into 12 one kilometer long lines that originate from a circle of 70 stones. At the western end of the Menec Alignment there once may have been a cromlech that was used as a religious sanctuary. The menhirs fan out from this point. The spacing between the stones is irregular and the line curve slightly. The tallest stones are about 13 feet in height. Many of the stones from the damaged Petit Menec alignment were carried off to make a lighthouse on a nearby island. Only about a hundred menhirs remain.

Kermario Alignment (near the Menec Alignment) are arranged more or less the same way. At the end of the Kermario Alignment, which contains 1,029 stones organized in 10 rows, is a passage grave, open to the public, that was once covered by an earth and stone mound. The lines of stones are longer than those at Menec. It is believed that the grave is older than the alignment. Near the grave is a ruined windmill and a visitors center with an elevated deck which provides a good view of the rows of stones. Kermario means "place of the dead." Kerlescan Alignment (near the Kermario Alignment) has 55 menhirs arranged in thirteen 400-foot-long rows with semicircular 29-stone cromlech at one end. Kerlescan means "place of burning."

Grand Menhir Brisé (Locmariaquer, Brittany) is the world's tallest menhir. Originally 67-feet-high and sometimes called the "Fairy Stone," the 340-ton standing stone is now in four pieces. The three top pieces lie neatly on the ground in a patch of heath. The huge base is flipped and twisted and pointing at an angle. In contrast the largest stone at Stonehedge is 29 feet high and weighs 50 tons. The 340-ton stone is believed to have been moved 2.5 mile from a nearby quarry site. On May 1st women from Locamarinauer slide down the stones without panties in hopes of getting pregnant.

Burials Chambers in Carnac

Also found in the area are 5000 year old tumuluses and dolmens. Many of the tumulus resemble small hills. The largest dolem, the Mané Rutuel, has a capstone, weighing 50 tons. The remains of young girls and cows, presumably left as sacrifices, have been in chambers near Tumulus of St. Micheal, Kercado (near Carnac) is a 7000-year-old burial mound passage grave with a 20-foot corridor of granite slabs that lead to a burial chamber large enough to stand up in. The walls and ceiling are comprised of granite slabs.

The Tumulus of St. Micheal is the most impressive tomb in the Carnac area. Resembling a small hill and capped by a small church, it is comprised of 1.4 million cubic feet of soil. This is where French archeologist René Gallas discovered an undisturbed main burial chamber in 1862 below 35 feet of dried mud and stone. Inside the chamber he found polished jadeite and fibrolote axeheads, necklaces made form turquoise-like callais, jasper discs and pendants, viriscite beads, pottery, arrowheads, burned offerings and "the cremated remains of the powerful and mysterious tenet of the burial mound."

Table of Merchants (near Grand Menhir Brisé) is a passage grave enclosed within a cairn. The engraved section of the menhir forms part of the roof. Another section from the menhir with similar engravings, weighing a dozen tons, was incorporated into the roof of the Er Vingle dolmen two miles away; and a third section was presumably floated by raft to the tumulus at Île Gavrinis three miles away in the Golfe of Morbihan. There also representations of theories of the origin of the monuments and dioramas that show what the everyday life of Carnac's prehistoric inhabitants. The museums gives out a good free map of the archeological sites.

Le Menec Carnac

How Were the Menhirs Moved?

How the menhirs were moved and raised remains adequately explained. In 2010 in Le Petit Mont in northwest France 30 tourists were enlisted to heave on a rope to move a 4.2-tonne stone block as part of an experiment probing the mysterious history of megaliths in the Brittany region. The participants found that among the things that were needed were vast quantities of muscle power and lots of patience. [Source: Sophie Pons, AFP, July 23, 2010]

"It's experimental archeology," explained Cyril Chaigneau, an architect who runs a programme on the megalithic sites of Petit Mont and Gavrinis in the Gulf of Morbihanm told AFP. "We're trying to find out how men from the neolithic period moved enormous blocks across distances of 10km (six miles) or more.

Sophie Pons wrote in AFP, No one today knows how or why the sedentary tribes that settled 7,000 years ago on this stretch of the Atlantic coast transported and then erected the menhirs, dolmens and other huge stone steles that dot the Breton landscape. Chaigneau's investigation focuses on the journey of a slab that makes up part of the dolmen on the island of Gavrinis, an engraved block of 17 tonnes that serves as the ceiling of a funeral monument built in 3,600 BC. Work carried out by other archeologists has established that this slab was in fact a fragment of another dolmen five kilometres away.

That huge structure was erected a thousand years earlier and stood 25 metres tall (82ft), was three metres wide and weighed around 300 tonnes. The stone it was made of came from a quarry situated 10km away. "The goal is to reconstitute the journey by land and sea or river but also to help members of the public get a practical understanding of prehistory, to engage the public in science in action," said Yves Belfenfant, the director of the sites of Gavrinis and Petit Mont.

Elisabeth, a banking executive from Versailles, was one of the 30 people trying to move the massive stone. She said she and her husband and their five children liked "cultural" holidays and that was why they wanted to take part in this experiment. "It's impressive to see this massive stone moving," she said.

The tourists managed to pull the stone 4.4m in about 12 minutes on their first stint, but by their fifth try their technique had improved and they pulled it 22m in 24 minutes. Jerome, a 36-year-old father, said he was taking part because he had "always wondered how the Egyptians built the pyramids". "This is far better than school to help you understand," said nine-year-old Valentine, who was proud of her part in pulling the giant stone forward across logs laid on the ground.

"You don't need magic powers to move a block, you just need a lever," said Chaigneau, who has programmed several stone-pulling events. The first such experiment in France was held in Bougon in western France in 1979, when 150 volunteers helped shift a block of 32 tonnes.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Mafia-style burials, CNN

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024