MERCENARIES IN ANCIENT GREECE

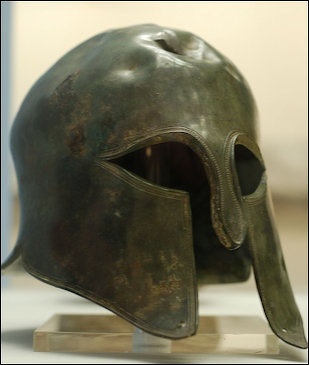

Spartan helmet

Mercenaries are generally defined as being professional soldiers paid to serve in a foreign army. Greek mercenaries fought for and against the Egyptians, Persians and others.

After the reforms of Cleisthenes in Athens in 508 B.C., it became customary for each tribe to elect a general , and for the chief command in time of war to fall to all these generals in turn, each commanding for a day. Next came the “Taxiarchs,” and the two “Hipparchs,” and ten “Phylarchs,” but nearly all these offices lost their importance, as did also the military organisation of the citizens, when the mercenary system was introduced. This began as early as the time of the Peloponnesian war, and gradually gained ground. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Originally Athens hired troops from other city states and foreign nations of a kind which were wanting in their own army; thus, javelin throwers were brought from Rhodes, and archers from Crete, but in the course of the fourth century the actual Hellenic population, and in particular that of Attica, became more and more unwarlike, and as the princes of Macedonia and other non-Hellenic states began to form standing armies of well-disciplined mercenary troops, the Hellenic republics were forced to follow this example as their own military power diminished.

This mercenary system did a great deal to undermine the independence of Greece, and facilitate its subjection under the Macedonian dominion. Even in the time of the Peloponnesian war, the Arcadians were willing to fight for anyone who would pay them, against their own countrymen; in the expedition of the Ten Thousand, they formed an important part of the troops of the younger Cyrus, and by no means the worst part. As the population was impoverished by many wars, they became more willing to respond to the invitation of any capable Condottiere, and collected from all states, but chiefly from Peloponnesus; and it sometimes happened that the members of a single state or tribe united together as a special division of the army.

As the warlike spirit disappeared among the citizens, who were unwilling to undergo the fatigues of service, these standing mercenary troops, under the command of excellent generals, became more and more disciplined and capable. The pay for a common soldier was usually four obols a day (about fivepence), half of which was pay and the other half ration-money; this amount was sometimes increased. The captain of a company received twice as much, the general four times, but the prospect of booty was even more attractive than the money; for according to the conditions of warfare of that time, every campaign was a predatory and ravaging expedition, and the mercenary troops who went to war from purely personal motives spared neither friend nor foe, and herein simply followed the example of their leaders.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Greek Mercenaries: From the Late Archaic Period to Alexander” by Matthew Trundle Amazon.com;

“The Mercenaries of the Hellenistic World” by G. T. Griffith (1968) Amazon.com;

“Greek Hoplite 480–323 BC” (Warrior) by Nicholas Sekunda (Author), Adam Hook (Illustrator) (2000) Amazon.com;

"Hoplites at War: A Comprehensive Analysis of Heavy Infantry Combat in the Greek World, 750-100 BCE)" by Paul M. Bardunias and Fred Eugene Ray Jr. (2016)

Amazon.com;

“Greek Hoplite Vs Persian Warrior: 499–479 BC” by Chris MacNab (2018) Amazon.com;

“Soldiers and Ghosts” by J. E. Lendon (2005) Amazon.com;

“Arms and Armour of the Greeks” by Anthony M. Snodgrass (1967) Amazon.com;

“Anabasis” by Xenophon (1847) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Armies” by Peter Connolly (1977) Amazon.com;

“Armies of Ancient Greece Circa 500–338 BC: History, Organization & Equipment” by G. Esposito (2020) Amazon.com;

“Greek Warfare: Myths and Realities” by Hans Van Wees (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece”

by Victor Davis Hanson and John Keegan (2009, 1989) Amazon.com;

“The Greek And Macedonian Art Of War” by F. E. Adcock (2015) Amazon.com;

“Warfare in Ancient Greece” by Tim Everson (2004) Amazon.com;

“Warfare in the Classical World” by John Warry, illustrated (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Wars of the Ancient Greeks” by Victor Davis Hanson (1999) Amazon.com;

“War and Violence in Ancient Greece” by Hans van Wees Amazon.com;

“Warfare in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook” by Michael M. Sage (1996) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Greeks at War” by Louis Rawlings (2007) Amazon.com;

Greek Mercenaries Hired by the Persians

The “Anabasis” (“March Up Country”) by Xenophon (431-354 B.C.) — an Athenian who fought for Sparta and participated in the march — is the story of the march by Greek mercenaries to Persia to aid Cyrus, who enlisted Greek help to try and take the throne from his brother Artaxerxes,. The march occurred between 401 B.C. and March 399 B.C.

“Anabasis” is Xenophon's record of the entire expedition of Cyrus against the Persians and the Greek mercenaries’ journey home. Xenophon Under the pretext of fighting Tissaphernes, the Persian satrap of Ionia, Cyrus assembled a massive army composed of native Persian soldiers, but also a large number of Greeks, to fight against his brother Artaxerxes, the king of Persian. [Source: Wikipedia]

On the recruiting of Greek mercenaries by Cyrus, Xenophon wrote in “Anabasis” (March Up Country): “The manner in which he contrived the levying of the troops was as follows: First, he sent orders to the commandants of garrisons in the cities (so held by him), bidding them to get together as large a body of picked Peloponnesian troops as they severally were able, on the plea that Tissaphernes was plotting against their cities; and truly these cities of Ionia had originally belonged to Tissaphernes, being given to him by the king; but at this time, with the exception of Miletus, they had all revolted to Cyrus. In Miletus, Tissaphernes, having become aware of similar designs, had forestalled the conspirators by putting some to death and banishing the remainder. Cyrus, on his side, welcomed these fugitives, and having collected an army, laid siege to Miletus by sea and land, endeavouring to reinstate the exiles; and this gave him another pretext for collecting an armament. At the same time he sent to the king, and claimed, as being the king's brother, that these cities should be given to himself rather than that Tissaphernes should continue to govern them; and in furtherance of this end, the queen, his mother, co-operated with him, so that the king not only failed to see the design against himself, but concluded that Cyrus was spending his money on armaments in order to make war on Tissaphernes. Nor did it pain him greatly to see the two at war together, and the less so because Cyrus was careful to remit the tribute due to the king from the cities which belonged to Tissaphernes. [Source: Anabasis by Xenophon translation by H. G. Dakyns from ,Dakyns' series, "The Works of Xenophon," 1890, Project Gutenberg]

“A third army was being collected for him in the Chersonese, over against Abydos, the origin of which was as follows: There was a Lacedaemonian exile, named Clearchus, with whom Cyrus had become associated. Cyrus admired the man, and made him a present of ten thousand darics[2]. Clearchus took the gold, and with the money raised 9 an army, and using the Chersonese as his base of operations, set to work to fight the Thracians north of the Hellespont, in the interests of the Hellenes, and with such happy result that the Hellespontine cities, of their own accord, were eager to contribute funds for the support of his troops. In this way, again, an armament was being secretly maintained for Cyrus.

“Then there was the Thessalian Aristippus, Cyrus's friend, who, under pressure of the rival political party at home, had come to Cyrus and asked him for pay for two thousand mercenaries, to be continued for three months, which would enable him, he said, to gain the upper hand of his antagonists. Cyrus replied by presenting him with six months' pay for four thousand mercenaries — only stipulating that Aristippus should not come to terms with his antagonists without final consultation with himself. In this way he secured to himself the secret maintenance of a fourth armament.

“Further, he bade Proxenus, a Boeotian, who was another friend, get together as many men as possible, and join him in an expedition which he meditated against the Pisidians, who were causing annoyance to his territory. Similarly two other friends, Sophaenetus the Stymphalian, and Socrates the Achaean, had orders to get together as many men as possible and come to him, since he was on the point of opening a campaign, along with Milesian exiles, against Tissaphernes. These orders were duly carried out by the officers in question.

Greek Mercenaries on the March

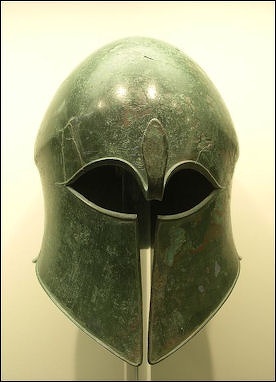

Corinthian helmet

Xenophon wrote in “Anabasis”:“But when the right moment seemed to him to have come, at which he 1 should begin his march into the interior, the pretext which he put forward was his desire to expel the Pisidians utterly out of the country; and he began collecting both his Asiatic and his Hellenic armaments, avowedly against that people. From Sardis in each direction his orders sped: to Clearchus, to join him there with the whole of his army; to Aristippus, to come to terms with those at home, and to despatch to him the troops in his employ; to Xenias the Arcadian, who was acting as general-in-chief of the foreign troops in the cities, to present himself with all the men available, excepting only those who were actually needed to garrison the citadels. He next summoned the troops at present engaged in the siege of Miletus, and called upon the exiles to follow him on his intended expedition, promising them that if he were successful in his object, he would not pause until he had reinstated them in their native city. To this invitation they hearkened gladly; they believed in him; and with their arms they presented themselves at Sardis. So, too, Xenias arrived at Sardis with the contingent from the cities, four thousand hoplites; Proxenus, also, with fifteen hundred hoplites and five hundred light-armed troops; Sophaenetus the Stymphalian, with one thousand hoplites; Socrates the Achaean, with five hundred hoplites; while the Megarion Pasion came with three hundred hoplites and three hundred peltasts ["Targeteers" armed with a light shield instead of the larger one of the hoplite, or heavy infantry soldier]. This latter officer, as well as Socrates, belonged to the force engaged against Miletus. These all joined him at Sardis. [Source: Anabasis by Xenophon translation by H. G. Dakyns from ,Dakyns' series, "The Works of Xenophon," 1890, Project Gutenberg]

“But Tissaphernes did not fail to note these proceedings. An equipment so large pointed to something more than an invasion of Pisidia: so he argued; and with what speed he might, he set off to the king, attended by about five hundred horse. The king, on his side, had no sooner heard from Tissaphernes of Cyrus's great armament, than he began to make counter-preparations. Thus Cyrus, with the troops which I have named, set out from Sardis, and marched on and on through Lydia three stages, making two-and-twenty parasangs [The Persian "farsang" = 30 stades, nearly 1 league, 3 1/2 statute miles, though not of uniform value in all parts of Asia.], to the river Maeander. That river is two hundred feet ["Two plethra": the plethron = about 101 English feet.] broad, and was spanned by a bridge consisting of seven boats. Crossing it, he marched through Phrygia a single stage, of eight parasangs, to Colossae, an inhabited city[4], prosperous and 6 large. Here he remained seven days, and was joined by Menon the Thessalian, who arrived with one thousand hoplites and five hundred peltasts, Dolopes, Aenianes, and Olynthians. From this place he marched three stages, twenty parasangs in all, to Celaenae, a populous city of Phrygia, large and prosperous.

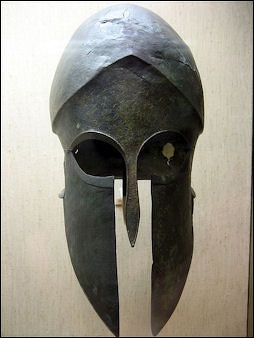

Greek helmet

Here Cyrus owned a palace and a large park[5] full of wild beasts, which he used to hunt on horseback, whenever he wished to give himself or his horses exercise. Through the midst of the park flows the river Maeander, the sources of which are within the palace buildings, and it flows through the city of Celaenae. The great king also has a palace in Celaenae, a strong place, on the sources of another river, the Marsyas, at the foot of the acropolis. This river also flows through the city, discharging itself into the Maeander, and is five-and-twenty feet broad. Here is the place where Apollo is said to have flayed Marsyas, when he had conquered him in the contest of skill. He hung up the skin of the conquered man, in the cavern where the spring wells forth, and hence the name of the river, Marsyas. It was on this site that Xerxes, as tradition tells, built this very palace, as well as the citadel of Celaenae itself, on his retreat from Hellas, after he had lost the famous battle. Here Cyrus remained for thirty days, during which Clearchus the Lacedaemonian arrived with one thousand hoplites and eight hundred Thracian peltasts and two hundred Cretan archers. At the same time, also, came Sosis the Syracusian with three thousand hoplites, and Sophaenetus the Arcadian[6] with one thousand hoplites; and here Cyrus held a review, and numbered his Hellenes in the park, and found that they amounted in all to eleven thousand hoplites and about two thousand peltasts.

“From this place he continued his march two stages — ten parasangs — to 10 the populous city of Peltae, where he remained three days; while Xenias, the Arcadian, celebrated the Lycaea[7] with sacrifice, and instituted games. The prizes were headbands of gold; and Cyrus himself was a spectator of the contest. From this place the march was continued two stages — twelve parasangs — to Ceramon-agora, a populous city, the last on the confines of Mysia. Thence a march of three stages — thirty parasangs — brought him to Caystru-pedion[8], a populous city. Here Cyrus halted five days; and the soldiers, whose pay was now more than three months in arrear, came several times to the palace gates demanding their dues; while Cyrus put them off with fine words and expectations, but could not conceal his vexation, for it was not his fashion to stint payment, when he had the means. At this point Epyaxa, the wife of Syennesis, the king of the Cilicians, arrived on a visit to Cyrus; and it was said that Cyrus received a large gift of money from the queen. At this date, at any rate, Cyrus gave the army four months' pay. The queen was accompanied by a bodyguard of Cilicians and Aspendians; and, if report speaks truly, Cyrus had intimate relations with the queen.”

Fighting and Pillaging by Greek Mercenaries

Xenophon wrote in “Anabasis”: “From this place he marched two stages — ten parasangs — to Thymbrium, a populous city. Here, by the side of the road, is the spring of Midas, the king of Phrygia, as it is called, where Midas, as the story goes, caught the satyr by drugging the spring with wine. From this place he marched two stages — ten parasangs — to Tyriaeum, a populous city. Here he halted three days; and the Cilician queen, according to the popular account, begged Cyrus to exhibit his armament for her amusement. The latter being only too glad to make such an exhibition, held a review of the Hellenes and barbarians in the plain. He ordered the Hellenes to draw up their lines and post themselves in their customary battle order, each general marshalling his own battalion. Accordingly they drew up four-deep. The right was held by Menon and those with him; the 15 left by Clearchus and his men; the centre by the remaining generals with theirs. Cyrus first inspected the barbarians, who marched past in troops of horses and companies of infantry. He then inspected the Hellenes; driving past them in his chariot, with the queen in her carriage. And they all had brass helmets and purple tunics, and greaves, and their shields uncovered. [Source: Anabasis by Xenophon translation by H. G. Dakyns from ,Dakyns' series, "The Works of Xenophon," 1890, Project Gutenberg]

“After he had driven past the whole body, he drew up his chariot in front of the centre of the battle-line, and sent his interpreter Pigres to the generals of the Hellenes, with orders to present arms and to advance along the whole line. This order was repeated by the generals to their men; and at the sound of the bugle, with shields forward and spears in rest, they advanced to meet the enemy. The pace quickened, and with a shout the soldiers spontaneously fell into a run, making in the direction of the camp. Great was the panic of the barbarians. The Cilician queen in her carriage turned and fled; the sutlers in the marketing place left their wares and took to their heels; and the Hellenes meanwhile came into camp with a roar of laughter. What astounded the queen was the brilliancy and order of the armament; but Cyrus was pleased to see the terror inspired by the Hellenes in the hearts of the Asiatics.

“From this place they endeavoured to force a passage into Cilicia. Now 21 the entrance was by an exceedingly steep cart-road, impracticable for an army in face of a resisting force; and report said that Syennesis was on the summit of the pass guarding the approach. Accordingly they halted a day in the plain; but next day came a messenger informing them that Syenesis had left the pass; doubtless, after perceiving that Menon's army was already in Cilicia on his own side of the mountains; and he had further been informed that ships of war, belonging to the Lacedaemonians (Spartans) and to Cyrus himself, with Tamos on board as admiral, were sailing round from Ionia to Cilicia. Whatever the reason might be, Cyrus made his way up into the hills without let or hindrance, and came in sight of the tents where the Cilicians were on guard. From that point he descended gradually into a large and beautiful plain country, well watered, and thickly covered with trees of all sorts and vines. This plain produces sesame plentifully, as also panic and millet and barley and wheat; and it is shut in on all sides by a steep and lofty wall of mountains from sea to sea. Descending through this plain country, he advanced four stages — twenty-five parasangs — to Tarsus, a large and prosperous city of Cilicia. Here stood the palace of Syennesis, the king of the country; and through the middle of the city flows a river called the Cydnus, two hundred feet broad. They found that the city had been deserted by its inhabitants, who had betaken themselves, with Syennesis, to a strong place on the hills. All had gone, except the tavern-keepers. The sea-board inhabitants of Soli and Issi also remained. Now Epyaxa, Syennesis's queen, had reached Tarsus five days in advance of Cyrus.

Alexander's army in Babylon

“During their passage over the mountains into the plain, two companies of Menon's army were lost. Some said they had been cut down by the Cilicians, while engaged on some pillaging affair; another account was that they had been left behind, and being unable to overtake the main body, or discover the route, had gone astray and perished. However it was, they numbered one hundred hoplites; and when the rest arrived, being in a fury at the destruction of their fellow soldiers, they vented their spleen by pillaging the city of Tarsus and the palace to boot. Now when Cyrus had marched into the city, he sent for Syennesis to come to him; but 26 the latter replied that he had never yet put himself into the hands of any one who was his superior, nor was he willing to accede to the proposal of Cyrus now; until, in the end, his wife persuaded him, and he accepted pledges of good faith. After this they met, and Syennesis gave Cyrus large sums in aid of his army; while Cyrus presented him with the customary royal gifts — to wit, a horse with a gold bit, a necklace of gold, a gold bracelet, and a gold scimitar, a Persian dress, and lastly, the exemption of his territory from further pillage, with the privilege of taking back the slaves that had been seized, wherever they might chance to come upon them.”

Cyrus told the Greeks their enemy was the Pisidians, and so the Greeks were unaware that they were pawns in Cyrus plan to battle against King Artaxerxes II the larger army. At Tarsus the Greeks became aware of Cyrus's plans to depose the king, and as a result, refused to continue. However, Clearchus, a Spartan general, convinced the Greeks to continue with the expedition. The army of Cyrus met the army of Artaxerxes II in the Battle of Cunaxa. Despite effective fighting by the Greeks, Cyrus was killed in the battle. Clearchus was invited to a peace conference and was betrayed and executed along with other generals and many captains. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The mercenaries, known as the Ten Thousand, found themselves without leadership far from the sea, deep in hostile territory near the heart of Mesopotamia. They elected new leaders, including Xenophon himself, and fought their way north along the Tigris through hostile Persians and Medes to Trapezus on the coast of the Black Sea. They then made their way westward back to Greece via Chrysopolis. +

Foreign Mercenaries Fighting Alongside the Ancient Greeks?

It is well-known that Greek soldiers frequently served as mercenaries in foreign armies but there is little evidence that foreign soldiers fought for Greek armies. Katherine Reinberger wrote: In 2008 a team of Italian archaeologists began to excavate outside the ancient city wall at Himera, a Greek colony on the north-central coast of Sicily, Italy. In the western necropolis, or cemetery, they found several mass graves dating to the early fifth century B.C. All the individuals in the graves were male, and many had violent trauma or even weapons lodged in their bones. The evidence strongly suggests these men could have been soldiers who fought in 480 B.C. and 409 B.C. in the Battles of Himera, written about by ancient Greek historians. [Source Katherine Reinberger, Ph.D. Candidate in Anthropology, University of Georgia, The Conversation, May 29, 2022]

Herodotus and another historian, Diodorus Siculus, both wrote about the Battles of Himera. They describe the first battle in 480 B.C. as a victory of an alliance of Greeks from all across Sicily over an invading Carthaginian force from modern-day Tunisia. Three generations later, the second battle in 409 B.C. was more chaotic. The historians report that Carthage besieged the city of Himera, which this time had little outside assistance. These ancient accounts tell of grand generals, political alliances and sneaky military tactics such as the Greek cavalry who pretended to be friendly aid to get into the Carthaginian camp.

The 21st-century discovery of what looked like the remains of soldiers from around the times of these two famous battles provided a rare opportunity. Interestingly, when when measured the strontium and oxygen isotopes in the teeth on 62 of the individuals, we found that the majority of soldiers from the first battle in 480 B.C. were not local. These soldiers had such high strontium values and low oxygen values compared to what we’d expect in a Himera native that my colleagues and I think they were from even more distant places than just other parts of Sicily. Based on their teeth’s elemental isotope ratios, the soldiers likely had diverse geographic origins ranging through the Mediterranean and probably beyond. On the other hand, the majority of soldiers from the later battle in 409 B.C. were in fact local. That finding supports the ancient sources that said the Himerans were mostly left unaided in the second fight, which allowed the Carthaginian force to overpower them.

The case of the soldiers from 480 B.C. suggests that Greek armies were more diverse than previously thought. Our results challenge earlier interpretations based on historical documents that the soldiers were Greek and points to the omission of foreign mercenaries in the historians’ accounts.The large variation in isotope values between the soldiers from our study strongly implies that there may have been foreign soldiers who joined the Greek side. Hiring foreign mercenaries could have changed the composition of communities in the Classical period, possibly providing outsiders a pathway to citizenship not otherwise available.

Did Archaeologists Find a Stash of Gold Coins Used to Pay Mercenaries?

Gold coins buried in a small pot and dated to the fifth century B.C. were discovered in modern-day Turkey and archaeologists believe — based on their location underneath a Helensitic house — they were meant to pay off mercenaries fighting for the Persian and Greeks in the ancient Greek city of Notion. Tim Newcomb wrote in Popular Mechanics: Mercenary armies weren’t cheap in the Greek city of Notion during the fifth century B.C. — especially with the Persian and Athenian fighters waging a front-line battle in the area. Getting a little extra muscle in the conflict likely required having a bit of spare cash on hand, and archaeologists recently uncovered some of that loot in the form of a hoard of gold coins, which they found buried in a small pot in western Turkey. [Source Tim Newcomb, Popular Mechanics, August 7, 2024]

According to researchers led by the University of Michigan, the gold coins — which were originally discovered in 2023 — depict a kneeling archer. The archer was a key signature of the Persian daric, issued by the Persian Empire and potentially minted during the fifth century B.C. about 60 miles northeast of Notion in the ancient city of Sardis. “The discovery of such a valuable find in a controlled archaeological excavation is very rare,” said Christopher Ratte, professor of ancient Mediterranean art and archaeology and director of the Notion Archaeological Survey, the project that discovered the coins, in a statement. “No one ever buries a hoard of coins, especially precious metal coins, without intending to retrieve it. So only the gravest misfortune can explain the preservation of such a treasure.”

According to the Greek historian Xenophon, a single daric was equivalent to a soldier’s pay for one month. Finding a hoard of the coins indicates the possibility that it may have been part of the payment to mercenary troops around Notion. While Ratte admitted that the evidence for the mercenary theory is “circumstantial,” he believes the timing adds up. Notion — along with other Greek cities on the west coast of present-day Turkey — became part of the Persian Empire in the mid-sixth century B.C. Then, come the early fifth century B.C., it came under Greek control. That didn’t last too long, however, as the early fourth century B.C. saw it return to Persian command until the conquest of Alexander the Great in 334 B.C.

All this back-and-forth rule made Notion the front lines of conflict, with Greek historians chronicling the use of barbarian mercenaries during Athenian vs. Persian skirmishes. It is battles like these that could have warranted an army collecting enough daric to pay for additional assistance, but any sort of defeat could have meant that the owners of the coins weren’t able to retrieve them, leaving... say... a pot of coins to be found centuries later.

Of course, the mercenary idea isn’t the only theory in play. As Notion was an important military harbor, the coins could have been part of payment to help build out the waterfront. If a tragedy befell the owner of the hoard, the coins would have simply remained secretly buried.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024